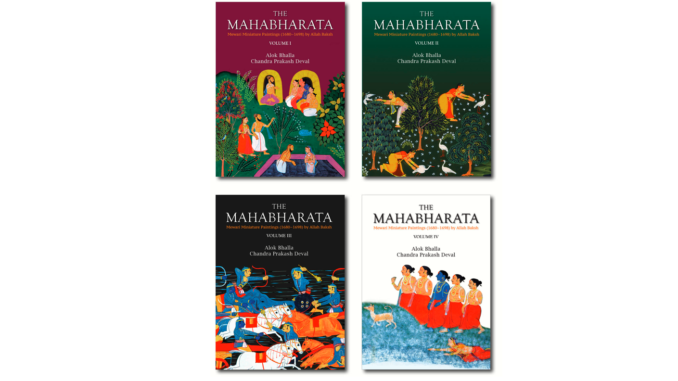

THE MAHABHARATA MEWARI MINIATURE PAINTINGS 1680-1698 by Allah Baksh. VOL I-IV By Alok Bhalla and Chandra Prakash Deval. Niyogi Books Private Limited; First Edition January 2023 1994 pages

Alok Bhalla*

‘The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.’—Plutarch

The Mahabharata opens with an irresponsible act of violence, a lament and a curse. The epic makes no distinction between the moral lives of sentient creatures; all are mortal; all suffer.

I have been a teacher all my life; I still am; and, like any teacher, I’m always anxious. A friend, who knows how I fret before a class, quietly advised, ‘Put aside your narcissism; don’t strive too hard this evening. Allah Baksh’s Mahabharata paintings, which have rarely been seen, are magnificent. The 5 volumes, with more than 2500 carefully printed colour plates, are gorgeously crafted artefacts. They are the collective labour of many people over six years. Let the readers feel the same anticipation and fission you did when Mubarak Hussain, the unassuming curator of the State Museum, opened a dingy little room in the great Udaipur Fort, unlocked a huge aluminium trunk, pulled out bundles of paintings wrapped in white muslin cloth and unfolded them on a rickety wooden table. At that moment, you understood what Plutarch meant when he claimed, ‘The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.’ So, lift up the volumes (at least virtually, since they weigh 9 kilos), take a bow and let everyone see why these paintings deserve an honoured place in the history of Indian miniature art…and, yes, don’t forget to recite the mantra by another great poet/painter/visionary you admire, William Blake, which always works when tamas (intellectual blindness, arrogance, cowardice) seems near: “Go, put off Holiness, and put on Intellect…Go tell them that the Worship of God is honouring his gifts In other men.” (Jerusalem, p. 738 and p. 739).’

Despite my friend’s advice, the protocol of this evening demands that I speak a little about the dialogic relation between Vyasa, the sublime poet of a great myth, and Allah Baksh, a strong reader, thinker and chitrakar. Since Allah Baksh paints the entire myth, verse by verse, chapter by chapter, he is a careful and a ‘slow reader’ who pauses over every story or mytheme, to understand its ethical place in the structure of the narrative, before sketching an incident and filling the space with colour. I reread the Mahabharata at the same pace as I studied the painting s and began to pay greater attention to the countless small stories. I began to imagine a new reading of the Mahabharata that neither overvalued the heroic individualism of the war-books, which form only a fraction of the epic, nor hurried past the nightmares the characters create for themselves to justify the workings of divinity or fate in whatever happens to them. The tragic story it had to tell was all too human. Vyasa’s epic became darker: its stories of empathy, love and friendship vanished, its forests burnt, its glittering palaces turned to ruins, its plains were flooded with blood and its wise men were reduced to wraiths.

Like the Ramayana, it could neither be reduced to a melodramatic war chronicle in which the divine party had the right to trample over asuric forces, nor read as a self-endorsing and self-approving dharma-book.

Vyasa, like Valmki, is neither a seer nor a warrior; neither a saintly saviour nor a populist of heroic nationalism. He is a great visionary poet who seeks and fails to find an answer to the only serious question that matters: Is it ever possible for a believer in ahimsa (non-violence) or anaramasya (non-cruelty) to survive in a world that is as brutal, callous and corrupt as ours? The stories he tells and the myth he imagines, bear witness to the fact the good is always frail, transient and vulnerable to destruction and decay. Present evil, he says, is only a repetition of historical violations of moral law. The future, he prophesises, will be more corrosive.

Allah Baksh’s critically distinctive and inspired engagement as a later-day reader and painter of Valmiki’s text is that he urges us to bring to the Mahabharata a double consciousness.

Don’t be hypnotised, he seems say in almost every painting, by the stories of power, wealth and religion, fratricidal quarrels and sexual misalliances, divine interventions in human affairs and demonic ambitions; be attentive, at the same time, to the earth’s loveliness, for beautiful forms can give solace to the eyes and save the soul from turning into stone.

Every scene is framed, like a sacerdotal space or a mandala, by three bands of colour adding to their beauty and giving them a feeling of calm sublimity. The broadest outer band is in vermilion–red, the colour of creative vitality, blood and hypnotic fire. Agni, the god of fire and of holy speech, plays a crucial role in cycles of destruction and creation in the Mahabharata. Agni always arrives when the epic’s narrative demands that the past and the old, which has become a burden, is burnt away for a radically new spark to rise from the ashes. Indeed, at the very end of the story, as the Pandavas abandon their kingdom and begin their last journey toward heaven, the embodied form of Agni, the god of fire with seven flames, blocks their path and demands that they cast away all their signs and symbols of power which can no longer serve them so that they can know who they are with clarity.

![]()

The colour of the innermost frame, which touches the space where human, divine and demonic events in the Mahabharata are depicted, is ochre-yellow. It is not as broad as the vermilion-red. Ochre-yellow is both the colour of the earth on which life in time is lived and of sunlight which illumines everything; it is ethereal and earthly and, is rightly, the colour of Krishna’s garments in the paintings. Separating the vermilion-red and the ochre-yellow is always a thin black line, silent and inconspicuous like death. Black, Goethe says, is an ambiguous colour of shadows and disquiet. It signals the deprivation of light, the negation of vision and dark thoughts, obscurity and ethical obtuseness.

In his theory of gunas, or the three qualities of the soul in the Gita, Krishna speaks of tamas (darkness) as a condition of dull inertia; as a state of empty moral abyss into which human beings can always fall when they fail to reach out in empathy to all things and all beings to make a meaningful world.

The other two gunas are sattva, the state of goodness, purity and harmony and, rajas, the state of outward driving passion, of imagination, which seeks to create something that is radically new. The ‘darkness’ of the framing line is the necessary condition for light and all the other colours of life to exist. Since the Mahabharata is primarily a story of deceit, exile, coercion, sorrow and war, the black line, perhaps, signals how dangerous life can become when we seek power over others, refuse to acknowledge their rights and defile them. Before looking at any illustration of an incident in the epic, the eye, as it moves across from the divine vermilion-red to the earthly ochre-yellow, must travel across this thinnest of black lines.

The three lines, then, can be read as a minimalist parable of the perilous journey the soul, any soul, must make as it struggles with emotions, desires and thoughts that pull it in different directions and produce either divine exaltation, earthly fulfilment or the despair of death (sattva, rajas or tamas).

Each and every story in the Mahabharata, the major ones about the gods, rishis and heroes or the incidental ones (akhyanas) about simple folk, animals and birds, describes the success or failure of this journey from crisis, through despair to redemption. The black line is the dark night of the soul, the dangerous passage through severe penances or difficult tests required for enlightenment; and, no one is assured of a successful crossing. A god like Indra can be punished for his presumptuousness, a rishi can lose his concentration, a wise man like Bhishma can be caught in a moral labyrinth, a hero like Karna can act with iniquity and a king like Dhritarashtra can fail to act righteously and so live a life of lamentation. For Duryodhana there is nothing higher than his earthly ambition; he remains mired in his ethical darkness.

![]()

Only Yudhishthira, perhaps, treads the passage between the earthly and the divine thoughtfully; he questions each decision and every move for its ethical implications for others. Taking nothing for granted, he never assumes that life in time is, as in myths, preordained. It is as if he understands that as he traverses the black line — the tamasic, the violent, the angry or the despondent in every human being — each step is a gamble which his reasoning self must take if it is to find a way through unreason and mendacity; every thinking person must risk (gamble) losing his sovereign self and yet remain calm; must gamble against loaded dice and the mendacity of a Sakuni. Indeed, Yudhishthira never ceases to question and debate, uncertain of the decision he has made or has had to make. Significantly, it is only at the gates of heaven that he finally and firmly makes an unambiguous, non-negotiable and dharmic decision: He will not enter heaven, he tells god, unless the mongrel dog, who may be despised by the ritualists as unclean, but who has walked with him across the difficult mountain path, is also admitted. It is at that moment when he ‘gambles’ with his salvation that all the three gunas (sattva, rajas and tamas) and all the three colours framing these paintings (vermilion-red, ochre-yellow and black) recover the old, the original harmony; the presence of each colour becomes the necessary precondition for the existence of all the others.

Perhaps, like most traditional artists of the sacred, a signature is not very important if it leads to no meaningful thoughts about the work. Our knowledge of Allah Baksh’s personal life or religion would make no difference to our response to the paintings because what they are illustrating is not anchored in the artist’s self or drawn from his experience. The references which guide our judgement are either in the Mahabharata text or in the painting itself — the cadence of its lines, the mood of its colours and the specifics of the story.

So, the work suggests that we are dealing with a man of strong moral imagination who intuitively understands that the Mahabharata is not a call to war in which everyone kills and dies according to some mythic prophecies whispered by wandering ‘moksha-talkers’; it is, instead, a plea — a hopeless one perhaps — for a more responsible way of becoming a dharma-being.

The lines are confident, the colours are vibrant and the space of every painting, suffused with light, is filled with an endless variety of animals, birds, trees, rivers, mythic creatures, gods and demons. These scenes may, at first, seem to be anomalous in works which are concerned with stories of violence and the slide of time into Kali Yuga (the age of darkness), but their insistent presence suggests that visions of beauty ought to form the normal environment in which life should flourish. These images are not created because they are part of the convention of Mewari art as decorative additions, but should be read as aids to reflections on the dharma of ahimsa whose erosion Vyasa bemoans throughout the Mahabharata. They encourage a two-fold response: one to the age of beauty and truth and the other to its erosion. That is why one is morally shocked when one comes across images and stories in which the gods conspire with heroes to burn forests down or wrathful men slaughter so many that lakes are filled with blood. Allah Baksh believes, like Vyasa, that there is no honour in such destruction; that suffering is not a condition of life but is always caused by people who do not understand that selfish power is ‘as insubstantial as burning flames fed by straw or the bubbles of froth seen on the surface of water.’

Vertical in form and large, their concern is with the pageantry of courtly life and the elegance of the princes, the excitement of the hunt and the heroism of war. In contrast, the scale of Allah Baksh’s paintings is human, ordinary, informal and playful. Their emphasis is either on the temporal world where people cultivate the land, build cities, gamble, read the Vedas, listen to stories, go on pilgrimages, treat forests carelessly only to be chastised by birds and animals, undertake penances, compete for a woman’s love with gods and rakshasas, talk endlessly about duty, revenge, suffering and forgiveness; or, their concern is with the sad destruction of everything that anyone has ever imagined caused by folly, arrogance, greed, fate and war. Simpler in line and form, their images are familiar and ordinary. The artist does not draw attention to himself as a sorcerer of colours or as an arbiter of dharma; he is neither an aesthete nor a preacher. Allah Baksh uses primary and natural colours which are conventionally associated with the sky, earth, heaven and hell, as if to say that the world clearly apprehended, free from the rust of dull perception, never requires an additional lustre; the war may have been catastrophic, yet it did not erase the footprints of human beings and animals, birds and trees, gods and demons. The story of the Mahabharata which he paints is, after all, being told to the later-day kings and descendants of the war and to the yogic renouncers of the world who live peacefully in forests. Its listeners must reimagine an ordinary world where human acts are good because they are self-directed and self-sufficient, and things are beautiful because they require no glitter of gold or mantras of power.

Related Readings: THE GITA: MEWARI MINIATURE PAINTINGS (1680-1698) BY ALLAH BAKSH. AN INTRODUCTION BY ALOK BHALLA

Narratemes of the Visual: D. Venkat Rao reviews The Gita. Mewari Miniature Paintining(1680-1698) by Allah Baksh.

— Painted Words. The Mewari Miniatures of Allah Baksh in The Gita: A Review by Bharani Kollipara

The paintings illustrating the Mahabharata folio, from the Adi Parva onwards, are horizontal, indicating that the epic tells a story which relentlessly follows the lives and fate of a people from their mythic beginning to their cataclysmic end. They gather together, in painting after painting, the beauty of creation and the debris of life in time; the movement from the threshold of eternity to the abyss of annihilation; the transformation from the first violation of the covenant between beings, a long history of wilful and erroneous selfhood, to the last conflagration. In contrast, the Gita paintings, are vertical and upward thrusting.

For Allah Baksh, the Gita is both a dramatic pause before the start of the battle, and a visionary breakthrough in the Mahabharata’s story of time, change and suffering. It is like a visionary flash when the divine breaks into human time and one is called upon to think only of that which is ‘eternally humane.’ (Frye)

A slow reading of each painting of the Mahabharata narrative and the illustrations of the Gita, suggests that Allah Baksh, who has, like Vyasa, meditated for long on images of war, still hopes that a painter’s imagination along with the poet’s song, can miraculously transform the earth from a charnel house into a household where a whole chorus of human beings and animals still possesses, as Spinoza says, the ‘right virtue to propagate what is just and beautiful’ and be ‘gracious to all.’

The gates of eternity, Allah Baksh understands, open only for those who have lived wisely, thoughtfully and in peace. Isn’t then, Yudhishthira, who has absorbed the wisdom of Vidura in his soul at the end, the only one who has earned the right to walk into heaven, the real hero of the epic? Like Vyasa, he is a storyteller and a thinker who says, what any significant artist says: We many lament human action and regret what we have done, but the work of creation never stops; we can be a part of it too. If there is an emotion or ethic which resonates throughout Allah Baksh’s paintings, it is the search for compassion or mercy in all relationships between man, nature and god.

Finally, I want to say to the government responsible for these paintings: Preserve and display these great works of art with the care and attentiveness they deserve because, as William Blake says again and again: “Art is First in Intellectuals & Ought to be First in Nations.”

***

*[Opening remarks at the book launch]

Leave a Reply