Alok Bhalla

‘What was the word, what the tree out of which heaven and earth were fashioned?’1

‘The World is like the impression left by the telling of a story.’2

‘Painting interprets the world, translating it into its own language.’3

I

n the Adi Parva (The Beginning), Vyasa says a few important things about the nature of the epic he has composed, its structure and its intention. Addressing Brahma, the supreme god, Vyasa says that he has ‘imagined’ a ‘poem’; a visionary ‘history’ (Adi Parva, p. 2) about the origin of the universe, its present travails as well as the future of heaven, earth, hell, human beings, animals, gods and asuras.4 His kavya, Vyasa tells Brahma, is an artifice on an epic scale about the perplexities of our moral life, the mysteries of chance and time, the ‘knotted’ riddles that fate poses for us, the displeasure of the gods, and the rust that often seeps into our souls and makes us obdurate like brutes. Vyasa, thus, makes a very clear distinction between a poetic work, a historical record and a moral discourse. A historian, he suggests, seeks explanations and causal connections between verifiable events in time; a priestly moralist repeats what he has heard from seers and bards. If the former is a scribe of the secular, the latter is a memorialiser of what he has only heard but not experienced. Neither of them are poets. Since his Mahabharata, Vyasa insists, is a transcript of poetic visions uniquely revealed, the answers to the moral, political or religious problems its stories raise can be found only within its structure; its tales are self-referential; the answer to the puzzle of any story is another story.

Brahma accepts Vyasa’s classification that his epic is a poetic revelation of the ‘divine word’, or ‘divine mysteries’, written in ‘the language of truth’: ‘Thou hast called thy present work a poem, wherefore it shall be a poem’ (Adi Parva, p. 4). Brahma adds that, since Vyasa’s ambitious work is equal in its imaginative and philosophic wisdom to the 18 Puranas, the four Vedas and all the Dharma Shastra, it renders, poetically, ‘the nature of decay, fear, disease, existence and non-existence,’ no mortal can inscribe it. Only Ganesha, he suggests, has the strength of mind, the intellectual audacity and boundless energy to record his mythic tale. As if to test Vyasa’s poetic genius, Ganesha at once lays down a condition: he will stop writing the moment Vyasa pauses and hesitates in his recitation. Vyasa, as if to test Ganesha’s ability to transcribe cosmic mysteries, lays down his own condition: Ganesh will write only that which he completely understands.

Vyasa says that his visionary Mahabharata is analogous to, and not an imitation of, the infinite and immeasurable world created by Brahma. Just as god’s universe emerged out of the single, mysterious utterance, his epic grew out of a small seed (an idea) into an enormous tree which is rooted deep in the earth, but reaches for the unbounded sky (Adi Parva, p. 5). Each story in it, he says, is either the root, the trunk, the branches, the sap, the knots, the pith, the leaves, the flowers, the fruit or the fragrance of that tree (Adi Parva, p. 5). Like the parts of a tree, all incidents in the Mahabharata are organically interrelated and follow their own inscrutable course. It is impossible to disentangle a tree’s structure to study it spatially, as one would a building, or temporally, as one would a chronicle. To know a tree one can begin either by examining its root and soil or trunk and branch, its leaf and flower or fruit and bole; the study of any one part requires the knowledge of all other parts (Adi Parva, p. 5). Similarly, one can begin to know his Mahabharata, Vyasa says, either by reciting its initiatory mantra or listening to the first story of Astika; either by assuming that what Krishna says contains its essence or by focusing upon the fratricidal war and pruning away all the countless small tales that form a part of the whole. Vyasa, as the teller of the tale, makes the task of selection both easy and complex by offering in the table of contents minimalist, but personally inflected, versions of the entire story by some of the main characters. Thus, Dhritarashtra, speaking to Sanjaya sometime after the war, laments that had he acted justly he could have prevented the annihilation of his clan; and, Sanjaya, recounting the same incidents, tells him not to grieve since the tragedy was fated: ‘It is Time that burneth all creatures and Time that extinguisheth the fire’ (Adi Parva, p. 14). Neither of them offers a reasoned analysis of decisions that led to the cataclysmic end of a thriving dynasty. What they say is prejudiced by their personal tragedies and narrow vision. Dhritarashtra only wants the psychological consolation of self-pity and has no words for the sorrow of others; Sanjaya is a good man who is overwhelmed by the ‘weight of sad times’ (phrase is from King Lear). We, as later day listeners, hear the stories as they are filtered past a series of narrators: Vyasa’s imagined tale is told to Vaisampayana, who narrates it to Arjuna’s great grandson, King Janamejaya, during a vengeful sacrificial ritual conducted to destroy the snakes for having killed his father, Parikshit. Vaisampayana’s narration, which persuades Janamejaya that mercy and forgiveness is the highest dharma, is overheard by Lomaharshana and passed on to his son, Ugrasrava (or Sauti), a wandering sage and bard. Ugrasrava, in turn, is persuaded by the peaceful ascetics in the Naimisha forest to retell it during their twelve-year holy sacrifice to dispel ‘the fear of evil’ (Adi Parva, p. 3). Before beginning the epic, Ugrasrava also briefly describes what the eighteen sections of the Mahabharata contain. (Adi Parva, pp. 17-32).

Strangely enough, even after all the retellings of the Mahabharata, its bardic seer, Vyasa, remains sceptical about its lasting power. The epic ends, as perhaps all epics do, with the poet’s tragic lament that his song of suffering and his plea for restraint, mercy, pity, peace and love may never find any listeners; that human beings may still continue, as they always have, to look at the earth through a glass darkly as a place where there can only be a perpetual clash between virtue and passion, wisdom and power (Swargarohanika Parva, p. 12).

Related Readings: THE GITA: MEWARI MINIATURE PAINTINGS (1680-1698) BY ALLAH BAKSH. AN INTRODUCTION BY ALOK BHALLA

— Painted Words. The Mewari Miniatures of Allah Baksh in The Gita: A Review by Bharani Kollipara

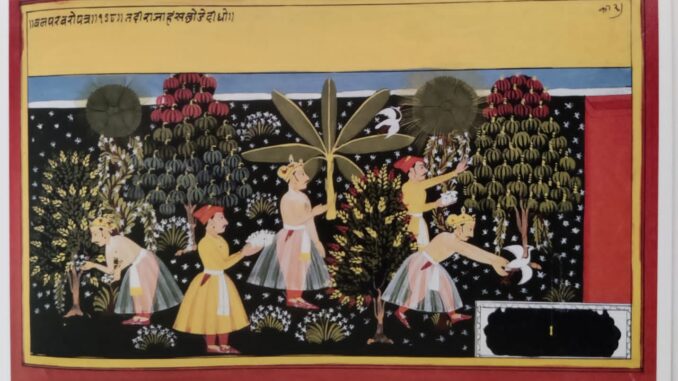

Allah Baksh’s Mahabharata neither begins by illustrating the long prelude about the visionary form and ahimsic intent of Vyasa nor by first visualising some act of heroism and sacred revelation. Instead, Allah Baksh begins with a story of an irresponsible act of ritual violence, a lament and a curse, before turning to the various narrators and their intentions. The left half of the first painting shows King Janamejaya and his three brothers, with golden crowns, sitting under a canopy with a red, green and white border. Janamejaya’s throne, which shimmers with gold, is placed on a red platform with a white border. Stiff, emotionally remote, forbidding and awkwardly crouched, Janamejaya is watching a pitiless rite of sacrifice that he has initiated, for the annihilation of all the snakes. Ironically, the ritual, with its hymns of destruction, is being conducted by two Brahmins somewhere on a gently undulating green land. Since the rite does not seek the well-being of the snakes but their extermination, the sacred flames in the altar, into which the snakes fall from the sky, seem like unrelenting and grim spikes. Interestingly, neither the king nor the Brahmins occupy the centre or the foreground of the painting. It is appropriate that an appalling scene about a holy rite demanding the annihilation of a species seems slightly askew. Janamejaya’s ritualised violence threatens the world once again with the same kind of destruction as his ancestors had unleashed.

Allah Baksh places four white and grey dogs at the centre and foreground of the painting. One of them is the divine mother, Sarama, who stands outside the ritual space and is shocked to see a scene of moral callousness being enacted within. A brother of the king is beating Sarama’s child, Deva Suni, with a stick and chasing him out of the sanctified space. Janamejaya’s brother declares that Deva Suni, who had unintentionally wandered into the demarcated area, has polluted the sacrifice by his presence and needs to be chastised for his sacrilege. In Allah Baksh’s painting, the prince chasing the dog seems to lose his balance as if to show how irrational anger always fails to recognise that all beings are equal and sacred. Deva Suni complains to Sarama about Janamejaya’s violence. According to mythic sources, Sarama is the favourite of Indra. As the daughter of heaven and earth, she is also the guardian of the path to heaven. One of the ethical principles of the Mahabharata is that to mistreat her or any animal, bird or tree with contempt is also to treat the entire creation with contempt; the life of each being is interfused with the moral life all beings. The top right of the painting shows Sarama, in her human form, standing in Indra’s court and pleading on behalf of her son and against Janamejaya’s rites of violence. With Indra’s permission, she curses Janamejaya. For his hardheartedness, she says, he shall suffer evil when he least expects it (Adi Parva, p. 33). Perhaps, for Allah Baksh, this painting about a small and seemingly inconsequential tale (a mythème) is a parable which contains the ‘seed’ of the entire Mahabharata. It is an example of how foolish it is to live according to codes of war and to assume that they not only define the destiny of a Kshatriya warrior but also have divine sanction. For Allah Baksh, the moral intention of the opening tale, the mythème, the building block for Adi Parva, is two-fold. One, he wants to show that seeking revenge for the accidental death of Janamejaya’s father is, like all acts of vengeance, in danger of setting off another long cycle of rage, violence and carnage after the great war at Kurukshetra. Two, he wants to suggest that in the Mahabharata what is ethically fundamental is the idea that living creatures are not placed in a moral hierarchy; human beings have no privileged place on earth and are as mortally vulnerable as any other being.5

The Mahabharata’s narrative then loops back to the cosmogonic moment when the gods and the asuras churned the ocean to fill the world with an abundance of things and fought over who should drink the elixir of eternal life. Allah Baksh’s illustrations of this story of origins, and the endless hostility between the gods and the asuras seeking absolute control over existence, are drawn with verve and animated passion. However, even as he captures the fury of war, the constant swing and swerve of armies, the threat of annihilation of all creation by various unappeasable ambitions (Parasurama, for example, slaughters all the Kshatriyas and fills seven lakes with their blood) or the ruthless destruction of the snakes by the divine bird Garuda, he never forgets to paint the gentler forms of creation. Every space in every painting that is not filled with clashing soldiers, grotesque asuras or gods armed with fearsome weapons is covered with flowers, birds, trees, clouds, meditating ascetics, fish in blue water and sky-boats with enlightened beings who have lived by the codes of non-violence, as if to suggest that the work of creation never stops. For Allah Baksh, it seems that the primal ethic of the Mahabharata is to urge human beings to turn away from ambitions of the self for power, from the hallucinatory dreams of warriors, kings and sorcerers, toward the fields, huts, bowers, ashrams, rivers and lakes where living beings have the time to conduct a continuous and endless dialogue with each other.

Sadly, whenever the heroes of the Mahabharata are offered boons, they ask for weapons, never for skills to heal or restore shattered lives. Appropriately, the final story of the Adi Parva is even more violent than the opening one. Arjuna and Krishna are, for the first and only time in the epic, enjoying a few peaceful moments of friendship in a beautiful grove when Agni demands that they burn, Khandava, the ancient rain forest along the River Jamuna. The forest is protected by Arjuna’s father, Indra, the god of rain. The irony is clear; heroic energy (symbolised by Agni) can only be demonstrated by relentless action and fierce conquest; a forest may be fecund and beautiful but the sedentary life of the forest dweller, which is merely repetitive, neither brings glory nor advances civilisation. Arjuna and Krishna must, henceforth, lead a life of force, danger, sacrifice and daring; they must not only be strong in the face of their adversaries, they must be ‘strong absolutely, the strongest of all.’6 Appropriately, in return for feeding his insatiable hunger, Agni gifts Gandiva, the invincible bow, to Arjuna, and the divine disc, Sudarshana, to Krishna. And, yet, they discover through all their wars that a compassionate regard for all existence offers a greater surety for the continuation of dynasties than force. Allah Baksh’s paintings of these scenes fill us with pity for the death of the creatures who have lived in the Khandava forest from the beginning of time rather than with admiration for the warriors who destroy it to build a new city whose survival will only be a fragment in the long duration of time.

The battle between Agni and Indra is fierce. Agni burns down the trees and dries up the lakes; Arjuna and Krishna kill all the creatures in the forest. It may be possible for critics hypnotised by deeds of courage to read this burning of the forest as an example of ‘well-regulated fecundity’7 essential for establishing cities and a necessary rite of passage for a hero. However, Vyasa’s descriptions of the agony of its inhabitants, and Allah Baksh’s horrified paintings, suggest that for both the poet and the painter, the destruction of a forest prefigures the destruction of a city founded on violence. That is why poets have often imagined that an ideal city of man is one which has gardens and is surrounded by forests. Indraprastha shall never cease to hear prophecies of war and its final destruction. Only six living beings survive the great conflagration: Maya, the demon of illusions; four Sarngaka birds who have been given a boon by Agni; and, Aswasena, the son of the snake King, Takshaka, who is saved by Indra so that some of the chthonic forces survive. This first killing of the snakes is the cause of Parikshit’s death and foreshadows the snake sacrifice by Janamejaya. Maya promises the Pandavas that, in return for his life, he will build a city on the cleared land whose magnificence would be the envy of the entire world. So, each story, each mythème, in Adi Parva feeds into other small myths, and the great epic about revenge, war and human illusions continues its relentless movement toward, Kali Yuga, the age of darkness.

******

[1] Rig Veda, 10.31.7. [2] Yoga Vashitha, Quoted by Alberto Manguel, Curiosity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 137. [3] John Berger, Understanding a Photograph (London: Penguin, 2013), p. 20. [4] All references to the Mahabharata are from Kesari Mohan Ganguli’s English translation and are included in the text (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2008). [5] See, Philosophy and Animal Life. Edited by Stanley Cavell and Cora Diamond (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008). [6] See Georges Dumézil’s famous justification for the burning of the forest and why it is the fate of Kshatriya men to undertake heroic exploits. Apsaras, he adds, adore such men. The Destiny of the Warrior. Translated by Alf Hiltebeitel (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), p. 106-107 and p. 113. [7] Dumézil, p. 77.

Alok Bhalla is at present, a visiting professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia. He is the author of Stories About the Partition of India (3 Vols.). He has also translated Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug, Intizar Husain’s A Chronicle of the Peacocks (both from OUP) and Ram Kumar’s The Sea and Other Stories into English.

Alok Bhalla in The Beacon

Leave a Reply