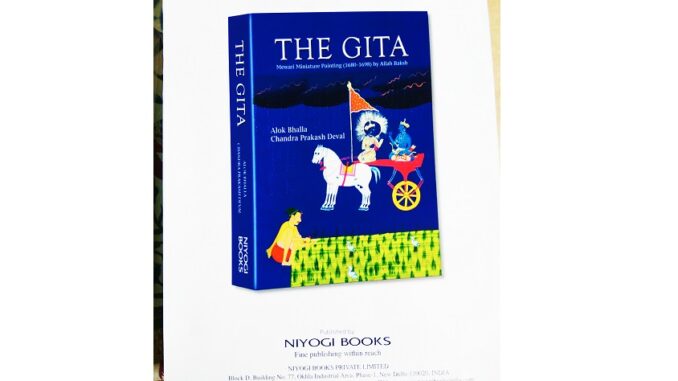

The Gita: Mewari Miniature Painting (1680-1698) by Allah Baksh Alok Bhalla & Chandra Prakash Deval. Niyogi Books Pvt. Ltd. October 2019. 484 pages

“What the visual arts are, and what art as such is, those are things which cannot be

defined by means of a chisel and hammer or a paint and brush,

but they also cannot be defined with the aid of a work

produced by means of those tools.” (Heidegger, 2022, 144)[1]

“We’ve become poor in order to become rich.” (Hölderlin cited in Heidegger)[2]

‘Art’ (painting and sculpture) remains a barely examined concept in modern India. Its millennial absence (from the Vedic times to the Ashokan period), belated emergence, protracted discontinuities and the neglected traditions of visualization stare at us quietly from a silenced past. Ill-thought socio-historical and political ‘interpretations’ of art flourish in the invasive modernity.

Yet, bewildering forms of visualization of Indian traditions (Puranic and itihasic themes) in sculpture and architecture sprouted and flourished in the common era. The Rajput, Mewar (especially), Mughal and Pahari traditions of visualization in colour ennobled and enriched the Puranas and the itihasa-kavyas over centuries. But in all these bewitching evocations of the smriti traditions, one finds an inexplicable and glaring absence: the stunning absence of visualization of the Bhagavadgita. Neither sculptural, ‘art’ nor musical or performative traditions dared to visualize this foundational composition (upanishadsaara) of Indian traditions. There is no explanation about such a startling absence. Neither the vision of the Mewar rulers (who excelled in the visualization of the Ramayana, Bhagavatapurana) nor that of Akbar (who commissioned the Mahabharata – The Razmnama) turned to the challenging task.

It is in such an enigmatic absence, only recently that an entire portfolio of the Gita from the Mewar court was brought to light. The portfolio with its glorious quantum of about 500 paintings was commissioned in the 17th century Mewar (during the reign of Rana Jai Singh). The portfolio is said to be a part of a colossal set of the Mahabharata (of about 3900) paintings and it is attributed to one Alla Baksh. The catalogue was brought out elegantly by the Niyogi publishers in 2019.[1]Alok Bhalla offers a fine erudite literary-philosophical commentary on the shlokas of the Gita and provides elaborate close readings of the paintings in this work. Bhalla also renders elegant translations of the relevant Gita verses in English.

The commentary is erudite and comparative. It takes a particular position basically with regard to the Gita (the text).

This position can be described as Gandhian and it depends deeply on Gandhi’s reading of the Gita. The gist of the Gandhian reading that runs through the commentary is that the Gita’s conception of action is essentially non-violent. This reading is at work in the interpretation of the folios of the Gita visual composition. The commentary is attentive to the paintings mainly to show how the non-violent action operates and how the portfolio upholds peace and harmony in the beleaguered world.

The singular Mewar contribution – the Mewar Gita – is an incomparable visual assemblage. It demands a compelling attention and an immersive response. The stunning visual schema (the festivity of colours), the delicate and effortless carve of the figural contours, embodiment of actional figuration, the ease of its responsive reception of the tradition, the experienced rendering of the colour of emotions and gestures, the seasoned and cultivated defiance of the dogmatic division of colour versus line – all these intimations impinge upon us and impel response from us (the viewers of today).

In conceiving such a response, the attention must move from the textual reading of the Gita to the figuration of the enigma of action – a task that appeared impossible until the event of the Mewar Gita. The monumental composition brought out recently challengingly stares at us from Mewar.

The Gita’s reflections on action, however, go beyond the specific kind of action which Arjuna is required to render in the crisis he is faced with; they pertain to the question of action in general. For, Krishna’s counsel reflects on the condition of formational existence: where action is ineluctable, what kinds of action to undertake in such unexpected and routine situations; the very nature of action and above all the non-relational relationship to action (focused rendering of action without indulgence and investment). Yet, it is difficult to say that the Gita gives prominence to any particular kind of action (actions of might and valour on the battle-field, ritual ceremonies, gifting, intensified ordeals or killing – there are series of folios on each of these themes in the Mewar Gita); nor is the Gita fixated on action as such to derive or codify some norms.

The Gita’s reflective intimations are subtle and nuanced: when action is inescapable, when the threat of indulgence impinges on any action, when all actions are open to indulgence, how to act? The Gita alerts one to such a double bind; this double bind, however, is not aimed at adumbrating an existential moral dilemma in certain grave or profound contexts (faith, individual vs. collective concern, commitment, parental or conjugal relationship). It is more oriented toward modes of being of instantial formations – where neither the instant nor the formation gets exclusively privileged: for, they are all seen as recursively trans-formative occurrences without an end or a beginning. The Gita’s intimations are, despite the apparent catastrophic theatre it emerges in, eloquent articulations of a reflective silence. Such intimations can orient and enliven action as performative reflections in instantial modes of being.

The Mewar Gita responds to these silent intimations in splendorous colours and brings forth something that has not been achieved so far in the Indian visual traditions.

Chromo Ludens

The Mewar Gita is an extraordinary play on colours. The play displaces any division between colour and line. The composition’s colour-scape can be said to be organized by 11 pigments; this array can be reduced to a set of 5 basic colours: white (slate-grey), yellow (green), red (brown, orange, pink) and blue (violet, purple). The colour play manifests in two significant ways in the portfolio: contrastive (sparkling white on dense or copperish black, or blue/yellow) or supplemental (varying range of related colours (red, brown, orange and pink) shades. The techniques of kshayavruddhi (varied intensities) and chavi (‘shading’) are eloquently at work.[2] The surfaces of the folios are made divergent with the dexterous use of the ‘brush’: swathes of the brush (letting the primer visible), smoothened surfaces, grainy on occasions, translucent, reflective illumination on occasions – the ‘ground’ of the folios is never homogeneous.

As we pay attention to the individuated paintings of the Mewar Gita we learn that it is an assemblage of visual narratemes, moods, modes and the affects that they entail. A narrateme is a reference or allusion to an unelaborated (but eminently open to elaboration) event, incident or experience from a life. Each such narrateme can be elaborated into a whole series of folios – but such a narrative elaboration is avoided here, as appropriate for the form of miniatures. Consequently, the individuated paintings often come across as elliptical and allusive complex of figurations. What goes into the composition of the assemblage is open to the painter involved. The painter seems to work with the ‘given’ conventions (colours, lines, iconography, moods, themes, and figures) in his own way.

How does the Mewar Gita picturize and articulate the enduring and cultivable conceptions that the tradition imparted? The Mewar painter seems to remediate the imports of the tradition through the shifting valences that the dynamic of the visual assemblage brings forth. Although the term assemblage might appear to incline towards emphasizing the spatial dimension, the visual complex treats the spatial along with the temporal commonly or conventionally; that is, these coordinates are neither exclusively valorised nor are they given any determinative historical significance. Thus the variedly differentiated ‘ground’ of the folio – differentiated with colour and line – be it the foreground, background, centre, margin etc., – does not state any value by placement. Often the iconic chariot with the figures is placed in different locations of the folios. The foreground or the centre, the size of the figures or colorations of them, that is, formations and their locations do not inherently project any idealization. For any valance of any element of painting must be seen in the assemblage of formations woven together by the visual composer.

The Mewar Gita’s assemblage is woven with contrasts, supplements and extensions. The folio attached to verse 3 of Chapter II, for instance, plays with the technics of the assemblage. Primarily the assemblage must respond visually to the fundamental concern of the Gita: the question of action. The painting (related to verse 2.3, p. 27) is composed of geometrical shapes of four rectangles in different colours (saffron yellow, intense and weakened greenish blues, the chilly-red foreground with visible swathes of the brush with noticeable whitish primer underneath) and the geometrical composition is framed by a prominent saffron-yellow inner line with black outer line and these are in turn surrounded by slightly longer chilly-red border which is prominent in the painting. Clearly the chilly-red foreground itself displays the contrast: the impetuous action of the battle-field (here appropriately done in chilly-red), the paralyzed action of the placid figure of Arjuna (contrasted with the vigorous gestures of Krishna aimed at spurring the former to plunge into action). Here Arjuna’s gesture is ambiguous. The inactive right hand listlessly folded across his chest holding (withholding) the left hand which is either lifting or dropping the golden bow into the chariot (the gesture of the right hand suggests that Arjuna is letting go of the mighty bow).

![]()

The luminously bright unrestrained white horses of Krishna’s chariot (only this and the next folio on this page have three horses – and the rest of the portfolio shows only two horses attached to the chariot) slightly bent stand quietly watching. In contrast to this dramatic counsel scene is the animated, restive impulses of the Kaurava army – rearing to plunge into battle (the trumpeting brown elephant with albino trunk and the restrained black and white horses). Reinforcing this drama is the single soldier with a drawn sword rushing ahead with the mark of lunar dynasty inscribed on his shield; however, the soldier appears to be a little uncertain, and he looks back over his shoulder, perhaps to see whether he is too early and solitary to plunge into action.

The image of the trumpeting elephant and the spurring rider on it crosses the red background of the battle-field and appears across the differentiated blue background on the upper side of the folio – indicating the non-isomorphic relation between the actional impulses and their differential locations. Impetuous action can take root on any ground. At the same time these (blue and red) backgrounds provide a striking contrast – and the contrast is directly premised on the import of the Gita pertaining to the question of action. Behind the ambivalently rushing soldier in the foreground is a strikingly faded black circular object lying on the ground. It is too early to see this as an abandoned shield. This almost insignificant object seems to have the image of a pale blue bare-chested figure who appears to have been half-drowned or sunk in either a slough or sea; the ‘drowning’ figure with raised hands in desperation seems to be crying or calling for help. He is all alone (like the lonely soldier rushing ahead). Strikingly in contrast to this drowning figure is the bare-chested figure with folded hands in a golden life-boat in the greyish blue waters in the upper rectangle of the painting.

These contrastive figures face the opposite directions (the figure in life-boat – moving east and the drowning one to the west). However, the directions – east and west – are not value-laden. For the portfolio shows 148 paintings with the east-facing chariot and in contrast it has 183 folios with the chariot facing the west. This goes once again to suggest that the elements of imaging – colour, shape, line – do not necessarily replicate any pre-determined codes of value. The visual response does receive the conventions but provides its own singular assemblage of elements and formations. Thus the figure of Krishna remains dark (blue or black) throughout (and takes purple tints in his manifestation of Vishwarupa– the colossal formation of tumultuous formations – later in the portfolio). The portfolio also incorporates the more recent convention (European through Mughal atelier) of attributing a halo to the Krishna figure or other divine figures. But this convention is not maintained consistently across the portfolio. Out of 384 paintings about 177 (of Krishna) are with halo and the rest without. The halo itself is not a copy of either the Mughal or European white or coloured smooth shining auratic disc; the Mewar Gita portrays the halo either as a nest of golden sparkles or a thick circle of thin gold lines radiating from the circle.

The life-boat in the folio 2.3, p. 27 seems to move on its own and the figure in it is un-invested in its movement; he is focused on something and it is that resolve that seems to makes him indifferent to the tumults of the sea of life he traverses. The traversal will move him out of the visual frame in an instant; whereas the drowning figure at the bottom is stuck in an abyss of life crying for attention. This figure is closer to the soldier poised to plunge into the battle but a momentary ambivalence arrests him from the plunge. In a way these two figures (apparently unrelated to the drama of the battle scene) frame the response to the shloka (2.3, p. 27) visually. In the turmeric-yellow rectangular band at the top a gist of the Sanskrit shloka is rendered in Mewari.

Clearly the painting here is not an illustration of the theme of the verse. On the contrary, it is a visualization of the complex performative reflection concerning action. The formation of the visual response is accomplished through nuanced contrasts and supplemental reiterations. One may say that the visual response here deeply resonates with the import of the Gita: an observant immersive response. The hasty eye can reduce the painting to what the verbal text proclaims and sees the assemblage as an illustration of Krishna’s counsel. Every painting in the portfolio can be said to repeat monotonously this very reductive theme as an illustrative work. Surely, the Gita can be reduced to a one-line didacticism: a teaching about action. But that would miss the verbal and visual articulation of enduring imports of the tradition, which the Gita renders in its singular mode.

Formational Grounds

In the geometrically organized portfolio of the Mewar Gita – often with rectangular blocks horizontally placed on a vertical folio – almost every painting shows the swathes of the brush work which let the white primer visible in some parts. That is, neither colour nor geometrical forms are symmetrically made within the inner borders of the painting. In a word, the visual response is brought forth by way of contrasts and consonances of colour, form, line and tracing the imaging of the theme. What brings together the entirety of the portfolio is the visualization of the question and the nature of action – action in a recursively trans-formative existence which has neither a beginning nor ending.

The transience of formations – inherently prone to change (be it repetition or trans-formation) – is both the condition and the effect of action. The Chapter II of the Mewar Gita brings forth this most resonantly in 52 folios (the largest set of images of the portfolio; every miniature folio is designed of 37×24 dimensions). Formations are both the media and the result of action. Such is the condition of action. Such a condition does not change on the basis of varied or differentiated formations and their locations. Whether the formation in question is a mighty king with regal accoutrements on the earth or a bare-chested saffron-clad learned man on a parasol sheltered by an umbrella in the realm of gods (as in 2.8, p. 33), the task and effect of action remain to be at work.

![]()

However, the placement of these two figures may be seen to suggest a hierarchy in their positions – the divine realm at the top in a serene white background and the terrestrial at the bottom. Arjuna’s questioning about action in the context seems to suggest such a hierarchy (what’s the point of gaining the realm of gods [like Indra] in contrast to the earthly king’s position through the task of killing the kith and kin?). Yet, as is visualized in other paintings, the logic of relation between action and formation undermines any such hierarchy. To indulge in such valuation of formations and offer a dogged defence or bemoaning their condition is the work of a learned quibbler, says Krishna. A pandit may indulge in such justification of hierarchic value. But the logic of relation is indifferent to such valuations. The relentless recursivity of formations and their ineluctable dissolutions is charmingly visualized in 2.14, p. 37.

![]()

A seductively dark olive green background provides the base for the quietly played out scene of emergences and eliminations of formations and elemental complexes in the folio. All elemental, vernal human and animal formations could be seen in an assemblage; flora: pink turned lemon-yellow-leaved tree aligned with a brown-stalked green flowering tree from which releases white-star shaped flowers from time to time on the lower left corner of the canvas. A learned man with red Vaishnava insignia marked over his bare upper portion with a long gold-embroidered stole with red borders hanging over both shoulders; he is well-adorned with rows of pearl necklaces, pendants, gold bracelets, a cap with floral design and red borders, and clad in a violet coloured dhoti seated on legs folded at knees, touching his wooden hand-rest – seated on a bright white elevated platform. On his right is the peacock-feathered fly whisk and on the left is a golden coloured water container (kamandala). Opposite him is a well-groomed royal personage, kneeling on the ground. Between the two figures is a plant with blossomed pink flowers and a little above another blooming plant with star-like white flowers. Behind the red-robed royal figures is an orange-yellow flame blazing with red finger-shaped flames – and adjacent to that on the lower right of the corner is a tree shorn of all leaves.

Placed between the floral bloom in a cool verdant shelter and blazing fire and bare ruined tree, the well-endowed learned and royal figures seem to be in some steady unperturbed conversation. In contrast, just above the flourishing vernal scene – but very much on the dark but alluring green background is the ubiquitous chariot with composed horses facing east with the dramatized expostulations of the interlocutors – Krishna and Arjuna. Their un-vocalized conversation can be guessed from the elliptical detail in the foreground with elemental, vernal and human formations. The vigour of gestures of Krishna and Arjuna in conjunction with the silent dynamic of the foreground suggest that the conjoined scenario pertains to the singular issue of the relation between action and formations – to that of confusedly invested accounts of life(and)-death.

Further up in the folio beyond the white band of the right upper corner in the blue-rectangular box with visible primer is the watchful but unaffected face of the sun drawn in shining halo with golden lines and a Vaishnava mark on the forehead. As an elemental formation, light (like fire, is associated with form in Indian traditions), this dazzling divine figure too is not free from the upheavals of life-death. The face of the sun appears to watch the gyrations of trans-formations – from within an instant of formational complex. Almost on the same plane as the face of the sun appears, the Hanuman figure is poised on the edge of the flag-post adorning the chariot. The Hanuman figure – done in gold – with folded elbows rested on bent knees – seems to watch calmly the dazzling sun.

What is striking about this folio – once one senses the work of the conjoined narratemes – is that it enacts the greatest of the themes (life-death) in the most enticing picturization. The contrastive but seductive coloration, the elliptical imaging of life-death, the quietness of the foreground and the dynamism of gestures of the interlocutors has no trace of violence or melancholy.

The overall flavour that the folio evokes is the quietude in the actional dynamic – quietude even as buffeted by the gyrating dualities (heat-cold, happiness-sorrow, birth-death).

When the eye learns to sense the contrasts and resonances of the colour, formations, shapes, shades, and the dramatizations of the scene – meditatively moving across the visual assemblage, then it can discerningly receive the performative reflections at work – both in the Gita and here in the Mewar visual response to the Gita.

[1] Martin Heidegger, On the Essence of Language and the Question of Art, translated by Adam Knowles, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022). [2] Ibid., p. 122.

[1] Alok Bhalla and Chandra Prakash Deval, The Gita: Mewari Miniature Painting (1680-1698) by Allah Baksh, (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2019). The translations of the Mewari verses into Hindi are by Deval. [2] Sri Vishnudharmottara Mahapuranamu, (Andhranuvada Sahitamu), 3 Khandas, translated into Telugu by K. V. S. Deekshitulu & D. S. Rao, edited by P. Seetaramanjaneyulu, (Hyderabad: Sri Venkateshwara Arshabharati Trust, 1988), p. 135.

*******

Venkat Rao is Professor at the School of Literary Studies, The English and Foreign Languages University Hyderabad. He is author of India, Europe and the Question of Cultural Difference:The Apeiron of Relations. Published July 30, 2021 by Routledge India 288 Pages

Leave a Reply