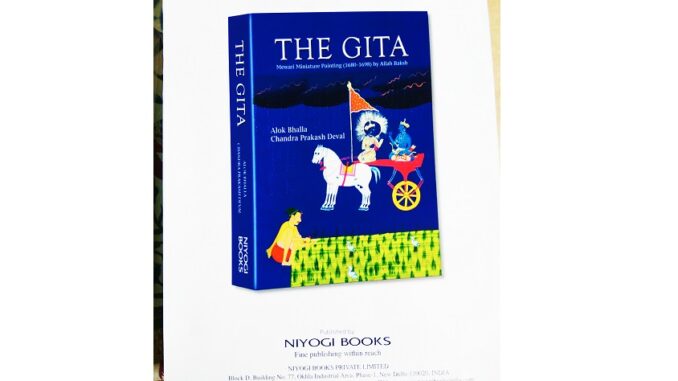

The Gita: Mewari Miniature Painting (1680-1698) by Allah Baksh Alok Bhalla & Chandra Prakash Deval. Niyogi Books Pvt. Ltd. October 2019. 484 pages

Painting is the best of all arts, conducive to dharma and emancipation….

The Vishnudharmottara[1]

T

he miniature paintings of the Gita, published here for the first time, are from the late 17th century Mewar. These paintings, created under the patronage of Maharana Jai Singh of Mewar, are part of the collections of three different museums in Rajasthan: The Government Museum in the City Palace, Udaipur; the Udaipur Sangrahalay, Ahar; and the City Palace Museum, Jaipur. The paintings belong to the Mewar School of Painting and should not be subsumed under the broader classification of Rajput Paintings.

The courts of the Rajasthani rulers were distinctive centres of cultural sophistication and were proud of their individual political lineage.[2] The inner form—the style, colouration, design, idiom, sensibility, images or philosophic thought—of these miniature paintings from Mewar is recognisably different from those painted in Bikaner, Kishangarh, Bundi or Jodhpur. Each school has its own uniquely illustrated version of Hindu epics, bardic songs, heroic tales and vernacular romances. There are, however, two important aspects that Rajasthani miniature paintings from 16th century onwards have in common. They use visual and literary production to assert the moral and political legitimacy of their kingdoms. This self-fashioning was important since they were being culturally and politically challenged by the powerful Mughal rulers who took pride in their discernment as connoisseurs of art.[3] From the time of Akbar (1542–1605), Mughal emperors had consciously commissioned translations and paintings of the cultural and religious texts of India to establish their own authority over the subcontinent’s complex and diverse traditions. Illustrated versions of Sanskrit epics and myths, local legends and songs gave them a frame to define their ambitions, understand the social and moral presuppositions of the people as well as envision a future for their kingdoms.[4] Akbar, for example, commissioned two illuminated manuscripts of the Ramayana in 1588 and 1594 (the latter for his mother, Hamida Banu Begum), and Jahangir used the genius of his court painters like Nadirul’asri Mansur, Bishan Das and Abu’l-Hasan to illustrate numerous Indian texts for his personal library. In response, in the 1640s, Maharana Jagat Singh of Udaipur gave two great painters of Udaipur—Sahibdin and Manohar—the task of creating a unique version of the epic on a grand scale. Each of them painted different sections of the Ramayana and put together a folio of more than 400 drawings. Maharana Jagat Singh also invited them to produce an illustrated version of the Bhagavata Purana. Sahibdin artistically transformed “the story of Rama’s suffering, heroism and devotion to duty…into a sophisticated expression of Rajput ideals and society.”[5] The rulers of Mewar, who preceded and followed Maharana Jagat Singh, cultivated painting as part of their project of resistance to the Mughal rule. Thus, during his days of refuge in Chawand, a small village in the Aravalli hills, Maharana Pratap Singh (1572–1597) gave Nasiruddin (Nasar Deen) the responsibility of painting the Ragamala poems in his own personal style.[6] It is possible that the father of Allah Baksh, the painter of this Gita folio, was Pyare Khan who belonged to the lineage of Nasiruddin.

The difference between the paintings from Rajasthan and the Mughal court is well defined by Ananda Coomaraswamy. Mughal art, he says, was refined, aristocratic and worldly. It was more interested in either commemorating the pomp and pageantry of courtly life or drawing portraits of emperors for posterity. In contrast, Rajasthani paintings, mainly inspired by popular Vaishnavism, were celebrations of the generosity of the divine which transfigures a common and ordinary world into a thing of beauty.[7] Emperors and palaces were alien and far removed from the everyday life-experiences of the painters from various regions of Rajasthan. Simpler in line and form, their images are sensitive and austere.

What gives these Gita paintings by Allah Baksh their significance is that they have no precedent in the history of Indian miniature art. Different art traditions of the country have, of course, painted romantic or dramatic images of Krishna as a lover or a charioteer.

These Gita paintings are, however, exceptional because the great religious poem has never been illustrated in its entirety, shloka by abstract shloka. There is no other miniature artist who has engaged with the song’s metaphysical argument with such calm intelligence and imaginative empathy.

The radiant beauty of the paintings suggests that for the painter, the Gita is a magnificent conversation between man and god about the pity and the sorrow of war; about how one can become more human-hearted; how one can ensure that our actions are life-creating and not merely self-directed. Their special emphasis is on the need to find a compassionate way of being on the earth, rather than on the call to arms for the sake of a kingdom. Allah Baksh’s works of visionary thoughtfulness deserve an honoured place in the history of Indian miniature art and in the great library of Indian scriptures and their interpretations. Unfortunately, very little attention has been paid to them.

As the Gita has 700 or 701 verses (the textual tradition is divided over number of verses in Chapter 13), we can assume that there must have been an equal number of paintings—one for every verse. Unfortunately, we have only found about 500 paintings and do not know the whereabouts of the rest. We have, for example, located only one painting each for Chapters 1 and 17. All the paintings are fairly large in size: 37×24 centimetres. The Gita folio is only a fraction of the 4,000-odd Mahabharata paintings by Allah Baksh in the collections of the three museums in Rajasthan.

![]()

Fig. 1: The script under the painting for Bhishma Parva: 52, identifies the artist of the entire Mahabharat folio commissioned by Maharana Jai Singh as follows: ‘Chitrakar Allah Baksh.’

The paintings in the Gita folio do not mention the name of the painter. We did, however, trace one painting from the Bhisham Parva: 52 of the Mahabharata narrative which is signed. An inconspicuous and hesitant note in the lower margin of the painting states that the ‘chitrakar’ or painter is Allah Baksh (see figure 1). We are astonished by the humility of the man and by his confidence in the idea that it is not the business of an artist to reveal himself. His greater task, instead, is to guide the reader of Krishna’s discourse and the viewer of the paintings to listen to the Gita in wonder—to listen to a song about the divine origins of the universe; to think in awe about what it means to be alive; and to ask, in sorrow, why the beauty of the inward soul that Krishna reveals is tarnished so often. The signature, however, only deepens the shadow of anonymity which surrounds the name Allah Baksh. It is possible that he belongs to the family of Nasiruddin of Chawand. We can surmise nothing more about his lineage and guess even less.

![]()

Fig. 2: This is the colophon for verse 72 of Chapter 2 of the Gita folio, which says that the paintings were commissioned by Maharana Jai Singh between 1680 and 1698 and that the Mewari text was written by Bhatt Kishandas.

The colophon of each painting is yellow-ochre in colour and carries a Mewari translation of the verse being illustrated. The text is written in black ink. The folio was commissioned by Maharana Jai Singh of Mewar and was painted between 1680 and 1698, as the notes appended to the paintings for verse 72 of Chapter 2 and for verse 43 of Chapter 3 tell us. The notes also informs us that the Mewari text was written by Bhatt Kishandas. The Mewari translation of the Gita makes no attempt to capture the sonority of Sanskrit poetry. Instead, it is written in simple, colloquial Mewari prose that renders the erudite arguments of the Gita accessible to any reader and speaker of Mewari. Krishna no longer speaks in classical Sanskrit shlokas to the scholar or the philosopher, but to ordinary men or women who care to listen, read and think.

It is important to add that one of the defining characteristics of this Mewari version of the Gita is that whenever Arjuna speaks to Krishna, he first calls out: ‘Hey, Krishna.’ His voice is intimate, friendly and devoid of fear; it is not a sublime address to the grandeur of the divine. It assumes, instead, an easy access of man to god and expects nothing but a conversation about how one should live in a world of violence—what is worthy, what is worthwhile. The quiet confidence of ‘Hey, Krishna’ is momentous, because one can imagine Arjuna saying to god a complex series of things:

I recognise your presence; I turn to you to help me think, so, draw upon the wisdom of ages to guide me; I shall follow what you tell me, but only if what you say respects my intellect and sounds right to my own heart. Therefore, Hey, Krishna, let your answer be offered as reverence to my mind so that I can honour the greatness of your own being and be in consonance with the finest of dharmic ideals. Anything less than that, offered as an anodyne for my present difficulty, would be a betrayal of my faith in the nobility of your imagination and of my friendship with the divine in you.

‘Hey, Krishna’ does not, therefore, sound like rapture; instead, it simply assumes Krishna’s mortal and earthly guise and makes him part of a dialogue about why and how we become participants in violence even as we long for peace. Krishna’s reply is equally generous and friendly towards a sincere man asking for guidance and illumination. Krishna invariably begins his response, not by admonishing Arjuna for his doubts and ambiguities, but by reaffirming his friendship, his commitment and moral attentiveness to a man’s anxieties. ‘Hey, Arjuna, listen,’ he says, as he calls Arjuna back from the abyss of despondency and urges him to think again about the need for ethical action. God in his wisdom knows how patiently the mind must be cultivated.

The accompanying paintings respond to the diction of the prose translation with their own rich-toned serenity. Their colours are clear, luminous and calm; their lines are restrained and precise; their images are meditative, unostentatious and drawn from daily lives lived in confidence; they are free from heroic posturing, spiritual pride and armed might. Together, they persuade one to pause and listen to the Gita again, not as a sermon which forbids discussion and debate, but as a guide to a thoughtful soul-seeking knowledge about how to live with others in peace. The paintings, like Krishna’s words, grow in the mind’s eye and acquire a moral significance.

The paintings illustrating the entire Mahabharata folio, from the Adi Parva onwards, are horizontal, indicating that the epic tells a story which relentlessly follows the lives and fate of a people from their mythic beginning to their cataclysmic end. The Gita paintings, however, are vertical or upright. There are some possible reasons for this significant decision. One is that the Gita is a dramatic pause in the narrative and a visionary breakthrough in the Mahabharata’s story of time, change and suffering. Before the war begins, Arjuna requests his charioteer, Krishna, to drive him into the no-man’s land between the two armies. Instead of seeing enemies at war, he sees friends and families, teachers and brothers preparing to kill each other for land, kingdom and glory. He is not only filled with anguish, but more importantly, he is also “overcome with great compassion”[8] and his “heart melts with pity.”[9] The emphasis of Allah Baksh’s visual interpretation of the Gita is on ahimsa or non-violence, and anarsamasya or the ability to feel the pain of others; the ability to discriminate between what the self desires and what it should renounce in the interest of others. Arjuna’s capacity to be horrified by war is a sign of his moral strength, not of his lack of courage.

In terms of narrative time, the moment of the Gita is brief. The Gita is preached in the Bhishma Parva of the Mahabharata during the short pause between the first hint of dawn in the horizon when the armies gather across from each other and sunrise which signals that the war can begin. It is like a visionary flash when, quite suddenly, the divine breaks into time, or when the debris of time and life fall away, and one thinks only of those deeds that are “eternally humane.”[10] The soldiers on either side only notice a spectacular instant. Arjuna, moved by pity, lays down his arms. Krishna drops the reins of the horses, and turns to reason with and bless him. Allah Baksh banishes the soldiers to the periphery. They are rarely visible in his paintings. His focus of attention is only the ‘chariot of learning’ on which Krishna and Arjuna sit discussing the ethics of war. The space around the chariot is miraculously filled with familiar images of the sky, earth, water, fire, trees, flowers, fakirs, lovers, music, birds, temples, idols, books, gods and goddesses; an ordinary world, which a moment ago was threatened by extinction, is now saved by the painter’s imagination and the poet’s verse; by allegories of peace, not threnodies of war.

The other reason for the verticality of these paintings may be that while the Gita is an integral part of the Mahabharata, it is not a linear narrative whose argument moves logically towards a conclusion. It is, instead, a dialogue.[11] As in any philosophic dialogue, what Krishna says can always be interrupted either by enigmas that puzzle the mind or by the need for repetitions and clarifications. The form of a discourse assumes that all the participants in the conversation have the moral freedom not to accept an argument or refuse to act till reason, in its integrity and honesty, is satisfied. A dialogue does not demand one’s surrender to any authority—transcendental or secular. This does not mean that what is said is either insignificant or unworthy. What it implies, instead, is that the concerns being explored are of extraordinary importance for the fate of earth; that the destiny of all living beings is dependent on what is disclosed and understood. Each verse should be read as a unique moment of revelation. No verse in itself is the answer. Every verse is distinct, and no single idea can be isolated as the essence of the Gita.

A slow reading of each painting reveals that Allah Baksh has meditated deeply on the Gita. He feels no scholarly or priestly compulsion to place special emphasis on a morally declarative verse which gives an unambiguous answer to Arjuna’s questions: ‘How should we live? Why should I, or anyone else, fight to seek revenge, save honour, overcome fear, feel envy, or crave for a kingdom or wealth? Are we not, each of us, in our fragility and transience, so linked to each other that injury to one is injury to the entire shristi (the universe)?’

Instead, the folio offers a different and more exciting interpretation. If there is an emotion or ethic which resonates through Allah Baksh’s painting of the Gita, it is the search for compassion or mercy in all relationships between man, nature and god.

This transforms the Gita into a dialogic journey; or, rather, a pilgrimage with a visionary guide who is always willing to give attentive replies to questions that trouble the soul; thereby, becoming an example of the most humane of Socratic ideas that to know the self, one must seek to conduct an unending discussion, not a dispute, in which nothing is enough and nothing is too much.[12] The poet of Katha Upanishad says:

Know thou the soul (atman, self) as riding in a chariot,

The body as the chariot.

Know thou the intellect (buddhi) as the chariot-driver.

And the mind as the reins. (III.3.3)

That is why image of Krishna and Arjuna on the chariot pulled by white horses is repeated in all the paintings in this folio. The chariot may, of course, be read symbolically as the composite image of the body, soul, reason and divine inspiration.

As Allah Baksh seeks a visual form for each verse, he pauses with meditative deliberateness on each verse without an anxious reaching for a final, conclusive answer. As we move from one painting to the next, it seems as if he is enacting a ceremony of words and images in search of wisdom. Is Allah Baksh unconvinced that war is inevitable? Does he feel, as Yudhishthira does in Sabha Parva, that Krishna and Arjuna on the chariot have been yoked together by destiny and are invincible in battle?[13] Their reappearance from painting to painting suggests that. Does Allah Baksh think that to read the Gita is to realise that its music of peace emerges from ‘old time’ and shall continue to be heard uninterrupted to ‘new eternity’?[14]

Unlike many commentators of the Gita, Allah Baksh is not ambiguous about the text. The Gita, he believes, asserts that a life of ahimsa is the inalienable adhikaar (right) of god and all living and non-living beings. That is why the visual space surrounding the chariot is free from the bluster and noise of war, the melodramas of heroic victory and defeat. There are, instead, an infinite variety of images of ordinary things and beings around the chariot. They create a serenity in which one can recognise the long and visionary history of the survival of gods, earth and human beings.

Of course, at the end of the dialogue of the Gita, the artist resolves, as Arjuna does, the mystery of who we are and how we should act by asserting that life has its beginning and end in the presence of Krishna.

This folio is the work of faith and not of scepticism. It is by an artist who longs, not for triumph, but for peace, for shanti, which Anandavardhana says is the final bhava (emotion) of the Mahabharata.[15] Perhaps, the dharma of Allah Baksh’s paintings is best expressed by the following lines from Ashvaghosa’s Buddhacharitra:

For to kill some helpless being to obtain results

Does not benefit a good and compassionate man,

Even if that rite yields everlasting results;

How much less when the results are ephemeral?[16]

The philosophic urge of the Gita is to postpone war for as long as possible; the tragedy of the Gita is that it is helpless to avert it; the greatness of the Gita is that human beings continue to meditate upon the dialogue, between god and man, about what is good and how it can be sustained.

********

[1] A Treatise of Indian Painting and Image-Making, translated by Stella Kramrisch (1928; rpt. Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press, 1993), p. 62. [2] Pramod Chandra, On the Study of Indian Art (Cambridge; Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1983), p. 107. [3] B. N. Goswami, Oxford Readings in Indian Art (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 277–79. [4] Audrey Truschke, Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court (Gurgaon: Penguin, 2016), pp. 244–47. [5] J.P. Losty, The Ramayana: Love and Valour in India’s Great Epic (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2008), p. 18. [6] Losty, pp. 6–9. [7] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy Rajput Painting (London: Oxford University Press, 1916), pp. 6–8; 14–15. [8] Italics added. Most translations and interpretations of Chapter 1, verse 28 focus on Arjuna’s anguished heart. Mahatma Gandhi’s translation, however, is radically different. He underlies the idea that Arjuna is overwhelmed by compassion. Mahadev Desai, The Gospel of Selfless Action Or the Gita According to Gandhi (Ahmedabad: Navjivan, 1946), p. 140. Hereafter, referred to as Desai in the text. [9] This is the translation of verse 28 offered by Shri Purohit Swami. It is different from Mahatma Gandhi’s but adds to the emotional resonance to Arjuna’s anguish. The Geeta: The Gospel of the Lord Shri Krishna (London: Faber and Faber, 1965), p. 17. Hereafter, referred to as Swami in the text. [10] The phrase is from Northrop Frye’s Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake (Boston: Beacon Press, 1947), p. 248. [11] Barbara Stoler Miller, in contrast, says that the Gita has a strong narrative drive. See ‘Introduction’ in The Bhagavad-Gita: Krishna’s Counsel in Time of War (New York: Bantam, 1986), p. 17. [12] Plato, “Protagoras,” Collected Dialogues, edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), p. 336. [13] The Mahabharata, vol. 1. Translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (1896; rpt. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2008), p. 492. [14] This is a variation of what Henry David Thoreau felt when he read the Gita. Paul Friedrich, The Gita within Walden (New York: State University of New York Press, 2008), p. 25 and p. 66. [15] For Anandavardhana, shanti or peace is the predominant emotion of the Mahabharata. See Alf Hiltebeitel, Nonviolence in the Mahabharata (London: Routledge, 2016), pp. 142–44. [16] The Life of the Buddha. Translated by Patrick Olivelle (New York: New York University Press, 2009), p. 323.

Alok Bhalla is the author of Stories About the Partition of India (3 Vols.). He has also translated Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug, Intizar Husain’s A Chronicle of the Peacocks (both from OUP) and Ram Kumar’s The Sea and Other Stories into English.

This author in The Beacon

I loved it!

A brilliant brief reading of the Gita along with a sensitive and humane interpretation of the paintings.