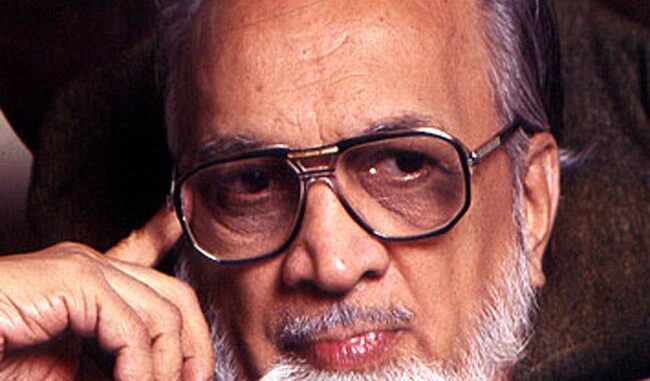

Vijay Tendulkar (06 January 1928-19 May 2008)

Balwant Bhaneja

Prelude

Vijay Tendulkar (1928-2008), India’s prolific playwright, wrote over seventy works which include 32 full-length plays, seven one-act and six children plays.(1) Nobel Laureate V.S. Naipaul described him as India’s best playwright. Tendulkar’s plays, though originally written in the author’s native Marathi, have been translated and performed in English.

The philosophy behind Tendulkar’s writing is based upon his perception of society and its values — his life experiences, and observing what he had seen in others around him: “I did not attempt to simplify matters and issues for the audience, though it would have been easier to do so through such a medium. Sometimes my plays jolted the society and I was punished…I was adamant as it is an old habit with me to do what I am asked not to.” (2)

On characterization in his plays, in his Sri Ram Memorial Lecture, The Play is the Thing, he states, “My characters are not card-board characters; they do not speak my language; rather I do not speak my language through them; they are not my mouth-pieces; but each of them has his or her own separate existence and expression. This is felt more in the original versions of my plays because of the nuances and variations in speech I attribute to my characters.” (3)

I had the opportunity to collaborate with Mr. Tendulkar, first as the translator of his play Safar, re-titled The Cyclist, then adapting it for BBC World Service in 1998, and further working towards its publication to which Tendulkar at last minute added another play, his first play in English –His Fifth Woman. He wrote that piece in a short period of six weeks while staging his classic, Sakharam Binder in New York. The two plays were published by the Oxford University Press (India) with a new title, “The Cyclist and His Fifth Woman” in 2006. (4) During this period, trying to understand Tendulkar’s enigmatic oeuvre, I met with him many times while visiting Mumbai.

**

E

ssentially, Vijay Tendulkar’s multi-faceted work deals with social and moral questions in a male-dominated Indian society. The basic urge to write for him has been to express his concerns vis. a vis. the social reality surrounding him. Silence! The court is in Session (1968), Sakharam Binder (1972), Ghasiram Kotwal (1972), Baby (1975), Kamala(1982) , Kanyadaan (1983), Safar/ The Cyclist (1999), and His Fifth Woman (2005) are some of his significant plays. (5)

Women characters have a central role in these writings, the lives of the characters determined by their location in a particular social space, mainly the lower strata of society and urban middle class. You see these characters as a housewife, a teacher, a mistress, a daughter, a film extra, a bonded slave, a kept woman, a servant etc. It is not just their social place but the broad spectrum of emotions which they bring to these characters – “from the unbelievably gullible to the clever, from the malleable to the stubborn, from the conservative to the rebellious, from the self-sacrificing to the grasping”. (6)

Violence and Self- Esteem

Psychological assault on self-esteem is a theme that underscores female protagonists in his work. Women characters are generally isolated and emotionally detached — insecure, solitary, and often deprived of their family connections or parental guidance.

In Silence! the Court is in Session, the lively school teacher Leela Benare who loves to recite fanciful poetry and participate in community theatre, realises that staging of the play-rehearsal as a mock-trial is in fact aimed at humiliating her. The trial accuses Benare of an illicit relationship she has had with a colleague Professor Damle and the illegitimate child she is carrying. Benare’s reaction is immediate. She recoils into herself wanting to shelter her privacy (and right as an individual). Responding to the court’s charade, there is a stern silence on her part. In one crucial scene towards the end, Benare is unable to restrain herself from expressing her innermost thoughts.

Tendulkar for this scene has the rest of the cast ‘freeze’ in their positions and lets Benare speak her private thoughts. It’s not clear whether she is addressing the court in actuality, or because of having been silenced by the court, the long soliloquy is an imagined conversation with her own self – her only way to defend. Benare has been informed by the court that because of her ‘immoral’ behaviour, she is being dismissed from her teaching position. Her lone response:

“…Milord, life is a very dreadful thing. Life must be hanged. Na Jeevan jeevanamarhati . ‘Life is not worthy of life’. Hold an inquiry against life. Sack it from its job! But why? Why? Was I slack in my work? O’ I just put my whole life into working with the children. I loved it! I taught them well! I knew that life is no straightforward thing. People can be cruel.

Even your flesh and blood don’t want to understand you. Only one thing in life is important –the body! You may deny it, but it is true. Emotion is something people talk about with sentiment. It was obvious to me. I was living through it. It was burning through me. But –do you know? — I didn’t teach any of this to those young tender, young souls. I swallowed that poison, but didn’t even let a drop of it touch them! I taught them beauty. I taught them purity. I cried inside, and I made them, and I made them laugh. I was cracking up with despair, and I taught them hope. For what sin are they robbing me of my job, my only comfort? My private life is my own business. I’ll decide what to do with myself; everyone should be able to! I’ll decide what to do with myself; everyone should be able to! That can’t be anyone else’s business; understand? Everyone has a bent, a manner, an aim in life. What’s anyone else to do with these? …Again, the body! (screaming) This body is a traitor. This body is a traitor. (she is writhing with pain). I despise this body –and I love it! I hate it – but – it’s all you have in the end, is n’t it? It will be there. It will be yours. Where will it go without you? And where will you go if you reject it? …”

Tendulkar does not take the easy way out. Even though there is no recourse for Benare to present her side of the story or to expose the duplicity of others playing the judge, lawyer, and court officials, he does not let Benare make a speech of remonstration. Instead he uses this opportunity for her to reveal her emotional trauma and pain.

In Kamala, Sarita’s self- esteem is threatened when the illiterate bonded-girl that her journalist husband has bought in an auction asks Sarita if she too is a slave in the household, and how much did her owner pay for her? This innocent query triggers in Sarita’s mind a series of questions requiring her to look at her marriage in a new light. The way her husband Jaisingh takes her for granted is not much different from the bonded slave Kamala.

In conversation with her liberal uncle Kakasaheb, Sarita questions the wisdom of such convention:

SARITA: …If a man becomes great, why doesn’t he stay a great man? Why does he become a master?

KAKASAHEB: Sarita, the questions you are asking have only one answer. Because he’s like that. That’s why he’s man. And that’s why there’s manhood in the world. I too was just like this…

SARITA: So Sarita, go behind your master like that. It’s your duty to do this – is that what you’re saying?

What is significant about Tendulkar’s two middle class female protagonists, Sarita in Kamala and Leela Benare in Silence! the Court is in Session is their desire to be recognized as individuals in their own right. Empowerment of Tendulkar’s characters comes from an awareness of the contradictions within, arising from nonfulfilment of their emotional needs and an unyielding social setting which stops them from outright revolt.

In Silence! the Court is in Session, despite the inquisitorial nature of the trial, the play’s resolution remains understated. All who conducted the mock-trial, withdraw quietly into the next room leaving Benare alone. While leaving they console her superficially that the whole thing was just a game, she should not take it to heart. It’s not clear that on their departure if Benare will take the poison from TIK 20 bottle lying on the table or not?

While this anguish for self-esteem in Tendulkar’s plays set in the middle class is restrained and muted; in his two other works that take place in Mumbai slums (Sakharam Binder and Baby), the playwright has ‘no holds barred’ for his physically and emotionally beaten-up female protagonists. Despite their limited range of choices which are deplorable, unlike his middle class protagonists, his lower strata women become master of their thoughts, emotions, and find a will to act outside the box. The results are mixed, sometime the mountain wins, sometime the mountain looses.

In Sakharam Binder, the play about a coarse Brahmin who instead of marriage prefers to pick desperate women deserted by their husbands as his co-habitants. Laxmi and Champa are two such characters with opposite personalities who consentingly opt to live as Sakharam’s comfort women. Laxmi the quiet one worships her new master as a God-fearing dutiful wife, whereas the rebellious Champa despite Sakharam’s strict code does not hesitate to have an affair behind his back.

In conditions of great poverty with social divisions and gender prejudices, opportunities for manipulation and exploitation are legion. Tendulkar’s male characters have a field day in exploiting their female subjects. Sakharam and Shivappa are two domineering male antagonists in these slum dramas. In Sakharam Binder, the play about a coarse Brahmin who instead of marriage prefers to pick desperate women deserted by their husbands as his co-habitants. There is general acceptance by his women that it was their choice and must adjust to the male violence imposed. They are acutely aware of consequences of any wrong doing on their part to hurt Sakharam on whom they rely for their sustenance. Champa while stopping Sakharam from beating Laxmi scolds him, telling him the reason for her interference:

“Because you will be hanged for murder, and to fill this belly of mine, I’ll have to start hunting around everyday for a new customer. Instead of having ten beasts tearing at me everyday, I’d rather do what one says to me. You get me?”

Interestingly it’s not men but the women in this play who are quick to point out flaws of the other. The criticism of Champa and Laxmi is mutual, the former chides the later as a “pious simpleton”, while Laxmi sneers at Champa calling her a sly “sinful” woman. Both however are cognizant of one another’s strengths and willing to accommodate other until their own survival is at stake.

Mrs. Kashikar in the Silence! the Court is in Session is another such critic. Her indictment of her teacher colleague Leela Benare is scathing:

“That’s what happens these days when you get everything without marrying. They just want comfort. They couldn’t care less about responsibility! Let me tell you — in my time, even if a girl was snub nosed, sallow, hunchbacked, or anything whatever, she–could–still –get married. It’s the sly new fashion of women earning that makes everything goes wrong. That’s how the promiscuity has spread throughout our society.”

Abuse of power, both overt and latent, has been a dominant theme in Tendulkar plays — “from humiliation, to revenge in assertion, to eventual victimization; played out against a background of political and moral decadence and degeneracy, with sexuality impinging on strategies of power.” (7) The power base eventually gets dissipated through interplay of actions, it’s not forced but evolves from the character’s motivation. Like in chess, the game goes on from act one to the next involving confrontation, challenge, accommodation, and resolution. Ultimately the character being challenged, is decimated, left with a sense of utter helplessness. (Silence! The court is in session, Kamala, Sakharam Binder, Kanyadan).

Detachment and Objectification

On the surface, some of these characters may appear ordinary, the playwright wanting to show these women in distress as victims; such an assertion will be flippant. The emotional content of Tendulkar’s plays is so finely tuned that it gets objectified by the characters carefully structured behaviour and societal predicament that leaves them little choice but to helplessly enact the inevitable role they must play. In this, a logical construction of opposites is developed as their future gets unravelled shaping the arc of their journeys.

Let’s look at Sakharam Binder again. We see him in the beginning of the play as a man in control of his world. By the end that power has been neutered by the actions of his two comfort women: one challenging him spiritually, the other sexually, both causing confusion and inner chaos in him. Eventually, Sakharam baited by Laxmi that Champa is having an affair with his friend Dawood, in a rage kills Champa. Sakharam is numb, speechlessly staring at the dead body of Champa.

Tendulkar’s Baby has a similar intricate male-female interplay. The hot headed slum landlord Shivappa’s in lieu of the rent from his hovel tenant Baby has total control over her. Not only she must share with this godfather authority-figure her earnings from film work, serve him liquor, offer her body for sex and be subject to his whimsical beatings; but to please her master she has to crawl submissively on her four and whine and lick him like a dog.

To be consistent with the character, Tendulkar doesn’t make Baby hit back Shivappa. Instead after being kicked in the stomach, she takes full blame for her misfortune. It is she who broke the trust by not fulfilling the conditions of the unwritten contract with Shivappa, and for that she must vacate the hovel and leave the shanty before dawn.

Tendulkar doesn’t judge his characters, making pronouncements on their virtues or weakness. In Baby, though the viewer wants her to rebel, Tendulkar leaves Baby in a quandary. The fate of Baby is not to be decided by the playwright or the audience, but by the choices available to the character.

Women in these plays come across as cold, insecure, doubtful, and distrustful – as if in a sort of abandonment of their self. Their isolation destroys the sense of being someone in other’s eyes, and their complete submission to others in fact destroys a sense of being a human in their own eyes. You see once in a while a glimmer of desire for an idealized life, an attempt to hold on to the self but the balance sought is so fragile that ultimately the cracks appear, and they remain broken for ever.

The actions and thought processes of Tendulkar’s male characters on the other hand show a consistent tendency to dominate the other sex. Their behaviour, despite their lofty pronouncements, remains paternalistic and violent. Only exception to this is the male protagonist in Kanyadaan–Jyoti’s father Nath Devalikar who remains vulnerable and torn throughout the narrative.

Kanyadaan is about Jyoti, a young educated woman brought up in a liberal higher-caste family who with her father’ s approval marries a lower-caste Dalit. It explores the facile texture of Indian modernity which such a marriage unleashes. Tendulkar was awarded the prestigious Saraswati Samman prize for Kanyadaan which literally translates from Marathi into English as ‘donating the daughter’, the Indian equivalent of ‘giving away of the bride’. Accepting the prize, Tendulkar noted that this play about domestic violence was not a story of a victory, it was an admission of a defeat and intellectual confusion. (8) It gave expression to a deep rooted malaise of the society and its pain.

Nath is conflicted between his high-minded liberal ideals and discovery of his latent despise for the socially under-privileged lower-caste Dalits. That has arisen from seeing his daughter subjected to beating by her Dalit poet husband Arun in an inter-caste marriage which Nath had himself encouraged. He cannot understand Jyoti’s acceptance of the rough treatment meted out to her by Arun. Nath’s fate at the end of the play is not that different from Tendulkar’s other male protagonists. Nath is bewildered, losing the upper hand he had been playing as the broad minded liberal father. In the last act, the father-daughter confrontation shows that it is now up to Jyoti alone to face up to her new situation:

“JYOTI: It will not happen, Bhai (father), because you yourself have taught us that one must turn one’s back upon the battlefield. It was you who always taught us that it is cowardly to bow down to circumstances. It was you who constantly intoned those phrases which never failed to get the audience cheering. And we also clapped and said, ‘Our father is a great man.’ You taught us those poems which said: ‘I march with utter faith in the goal; ‘I grow with rising hopes’, and ‘Cowards stay ashore, every wave opens a path for me.’ .we shall continue to recite ‘March on, Oh Soldier!’ and continue to lose our lives as guinea pigs in the experiment, and you, Bhai, you will go on safely rousing the god sleeping in man.

NATH: (In pain) Jyoti, don’t say that. Wait, Jyoti. Please don’t go away like this. Let’s give some more thought to it.

JYOTI: You think about it, I have to stop thinking and learn to live. I think a lot. Suffer a lot. Not from the blows, but from my thoughts, I can’t bear them much longer. forgive me, Bhai. I said things I shouldn’t have. But I couldn’t help it. I was deeply offended by your hypocrisy. I thought: why did this man have to inject and drug us every day with truth and goodness? And if he can get away from it at will, what right had he to close all our options?

(With certitude) Hereafter I have to live in that world, which is mine.(pausing) and die there. Say sorry to Ma. Tell her none of you should come to my house, this is my order.”

The emancipation of Tendulkar’s female characters is subtle; personalities involved must work out their emotion and intellect; espoused values and conflicting actions; seeking independence yet compromising, struggling between physical desires and conscience. Tendulkar’s oft statement that his characters define the play in itself is confirmation of a vantage point – in which he is watching the whole process of character development from the outside. This capacity for detachment vis a vis himself and life in general, provided Tendulkar an ability to hold back his emotions, retiring into himself like his Nath character in Kanyadaan, and viewing the world as it unfolded. Those who have followed Tendulkar’s life as a social activist would see in this one play his struggle to distance himself as the social reformer father from the Nath character.

In His Fifth Woman, despite the play’s solicitous title, the viewer never gets to meet its female protagonist. In fact, the Woman character spoken about is already dead. Sakharam is waiting in the hospital yard to claim the dead body of the woman after its post-mortem, pondering whether he has any responsibility to make such a claim. The play is not about Sakharam’s love or atonement of his wrongs but about broader existential questions of life, death and afterlife. It is rather a continuation of the play Safar/The Cyclist where instead of a strong woman protagonist, in this allegorical drama, he introduces a Mermaid (woman in a fish’s torso) who swallows the cyclist’s clothes, leaving him bare to the bone. The Mermaid’s seduction of the traveller is that of Oedipus, a composite of mother, girl friend, and enchantress. The cyclist’s journey is a carefully structured voyage into ‘the dark night of the soul’ unravelling man’s dehumanization in the face of society.

In August 2005, in an email I asked Mr. Tendulkar, “How and why is this focus on women central to your work?” His reply was that of a psychologist: “There is always a woman in most men’s psyche. And man in most women. The balance is never perfect. One may have the woman factor dominant in him by which he has an instinctive understanding of women. Or the man factor in him which generates a natural interest in women. The two are different and the difference shall be felt by the reader. In the first instance the woman in his writing will be more a-physical and more of a woman in the core. In the second instance the woman in his writing will be essentially a sensuous, physical creature with other aspects like emotions etc. But the stress in both will be different; and also the women they create in their writing. I say this when asked but also caution that it may be only a theory.” (9)

Ultimately, the inner core of Tendulkar’s plays came from his deep compassion and respect for human life – for life in general. Seeing its exploitation and waste, his response came through his unrelenting literary output and non-stop social activism. His plays seeking to comprehend the changing Indian reality showed balance, equilibrium, reconciliation and synthesis. Tendulkar’s personal views and thinking in this regard leaned towards championing the rights and individuality of female protagonists.

***

References 1.For a comprehensive listing of Vijay Tendulkar's works, see Vijay Tendulkar,(2001), New-Delhi: Katha, pp. 149-150 2. Ibid., p.37 3. Sri Ram Memorial Lecture, The Play is the Thing, New Delhi: Sri Ram Centre for Performing Arts, p.5 4. Vijay Tendulkar and Balwant Bhaneja, (2006), Two Plays by Vijay Tendulkar: The Cyclist and His Fifth Woman, New Delhi: Oxford University Press , 2006, pp.79 5. The English texts of the plays in this article have been used from the following sources: Vijay Tendulkar: Five Plays, (1992), Bombay: Oxford University Press, pp. 357. The five translations are: Kamala, Silence! The Court is in Session, Sakharam Binder, The Vultures, and Encounter in Umbugland. Translations are by Priya Adarkar, Kumud Mehta and Shanta Gokhale. Vijay Tendulkar, Kanyadaan, (English translation by Gowri Ramnarayan) , (1996), Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 71 . Vijay Tendulkar, Baby ( Hindi translation by Vasant Deo) (1987), New-Delhi: Vidya Prakashan, pp. 71 6. Shanta Gokhle, "Tendulkar on his own terms" in Vijay Tendulkar, (2001), New-Delhi: Katha, p.81 7. Vijay Tendulkar: Ghasiram Kotwal, (English Translation by Jayant Karve and Eleanor Zelliot) (1986), Calcutta: Seagull Books, Introduction by Samik Bandyopadhay p.v 8. Tendulkar's Saraswati Samman award-accepting speech quoted in Vijay Tendulkar, (2001) op. cit., p.35 9.email from Vijay Tedulkar , 4 January 2005

Balwant (Bill) Bhaneja is author of six books including Troubled Pilgrimage: Passage to Pakistan (TSAR/Mawenzi, Toronto, 2013); Quest for Gandhi: A Nonkilling Journey (Center for Global Nonkilling, Hawaii, 2009); and in collaboration with Vijay Tendulkar, Two Plays: The Cyclist and His Fifth Woman (Oxford University Press (India), New-Delhi, 2006). A former Canadian diplomat, he holds a PhD from Victoria University of Manchester, UK.

.

This is a remarkable write-up giving a new perspective to literature and society. Psychological violence is the worst form of violence that both men and women suffer from, for it is difficult to prove them.