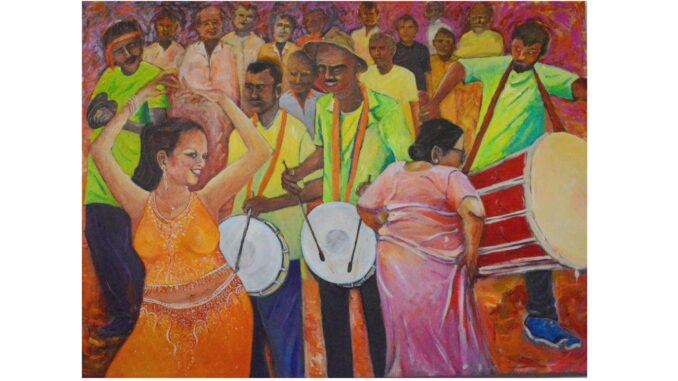

Indo-Trinidadian painting by Shastri Maharaj Image courtesy Loop eews

Cyril Dabydeen

Anglo-Saxon Ethnic

1

Begin with the parable of a remembered place

where he is comfortable with style and form,

rhythms of another country, but always

with a will to understand one’s own.

Absolute, infinite, or uncompromising:

what I will come to grips with taking

heed that things will change, or forever

remain as they have been for centuries.

Now it’s desire or instinct here at the edge

of the Amazon, not the Thames: places

yet undiscovered I now consider, indeed

familiar truths we will learn to live with.

This rage or desire in foreign places–

with civilization at my fingertips, or coping

with what the indigenous peoples consider

their own and harbouring new beliefs.

2

Constrained to being in one place only

with its own secrets, the tribe’s own, and

memory I will contend with trying to

understand myself better over the years.

This drama played out in territories,

like a burning desire, or my being

discreet about origins and knowing who

we’re not but familiar with indeed–

living in one place; and the burden

we yet bear or believe in, like only

a conviction of past years, and indeed

what will remain longest.

A Visit to India

1

A place I have never been to before,

but intrigued about since childhood;

Bihar or Mumbai, as the indenture spirit

is at a standstill: archives in me–

making much ado about history, or

being a gymnast late at night with

images from The Royal Reader. Yes,

tigers roaming, elephants marauding,

Shakuntala again pouring out with rain.

.

Where my ancestors have come from,

I pretend to acknowledge or not understand

having denied other places from times past,

or living with lore of the Amazon instead:

evergreen forests bolstering a greenhouse

effect as environmentalists talk loudest.

2

Now in Ottawa in an Indian restaurant

with a Mexican name, the waitress takes in

Chandra Mohan, our Indian guest in authentic

attire, who mutters about Chairs of Canadian Studies

in India, if indeed making Canadian Literature

better known to a billion people there–all

in Delhi, Calcutta or Chennai, and where else?

Now James Reaney’s an institution, he adds,

though he likes Margaret Atwood best.

So I ask, Why the interest in Canada?

Indeed it’s about Rudy Weibe’s Big Bear,

Robert Kroetsch’s post-modernism, and

language-use in the Prairies while I come

to grips with a tropical itch, being only

foreign-born and mulling over ways

of coping with identity in Canada.

3

Post-colonialism strides I contemplate–

or Nehru’s jewel-in-the-crown test, if tryst

with destiny, Empire what my forefathers took

less seriously while I’m in the Great White North:

a Susanna Moodie frontier in me

as I claim to be a drawer of water and hewer

of wood, then dwelling on the image of a garrison

state because of the neighbour to the south,

survival instincts merely–

Imagining continents that were once together

as metaphors now make the world one; and

I will again conjure up images like false truths,

reinstating Mowgli because of Kipling–

being astride an elephant and trundling along

in a jungle safari with bwana shouts, blowing

my horn because the British had been

–in India longest.

Now self-contained with aspirations

or a further quest I think about, what might

have been in Jaipur or Shimla unknown to me,

but being a maharajah, you see,

in an exotic wilderness.

On A Local Train In Mumbai

(for Coomi Vevaina)

After taking in Elephanta:

and the trimurti

out on an island

on a sweltering hot day,

I enter the train

in Mumbai with you, Parsi

scholar, and watch people

huddling, all trying

to get in, along with

the many tourists.

The crowd not defeated,

but with an accustomed ease

or frenzy due to their state

of poverty or what seems like it;

and two young girls:

eight or nine, with eyes large

as a cow’s, shabby clothes worn

past their knees in more than

being unique in style.

And you say in India it’s so special

because of what

has to be learned,

or endured

as a movie-star handsome youth,

determined at the back–

plays mournfully on his harmonium;

the train moving along,

and he sings a bhajan, yes–

to establish the right mood.

The two girls take their

turn to ask for alms,

coming to us next–

as I long to stand up

and listen to the centuries unfolding;

the girls’ eyes wider…

as an entire continent

opens up before me.

While across the Arabian Sea,

Elephanta’s images still form,

the train chug-chugging along–

and I will record sensations

with affection, or simple love

I can never truly return.

(November 1, l997)

The Visitors Have Come

Poetry is always in

unfamiliar territory

Margaret Avison

Time out, and there’s laughter

with voices that talk back without

remonstration, as we declare

who we are without a fanfare;

and the clothes we wear

in a forgotten style–

being natives only.

Oh, never that again, I hear

you say, in a wider world,

smiles at every turn–

all we bear up to.

Conquest in the mind’s eye,

guns firing, shiploads of men

carrying bayonets, an

hallucination only–

I hear you say.

Paradise lost; and how far away

is the sun as we beat our breasts,

strangers being all around,

people whose names we can

hardly pronounce, but grimace only

at their mannerisms.

So it’s once more crossing an

ocean, or being in the latter-day

jet that won’t come down–

the airport rises up suddenly,

a deafening noise really.

Hands before faces we are about

to scream once again going through

Immigration and Customs: an upheaval

of sorts, being dead-set against

the ice and cold.

So it’s starting over with emblems,

waving a flag, or being house-guests

with fortitude and forbearance–

thinking we’ve never been here before

–pent-up emotions all.

Now it’s what’s still to come,

bolstering faith and being at the will

of the imagination, merely–

all we are left with, bound

to one place because of what

we have finally come to accept.

Praising you

Praising you,

or encountering longings

beyond nostalgia

Shutters of daylight,

a hen’s beak

being spitfire

You telling me of the woman

anxious about her missing child

after an abortion–

Once a prostitute,

she will soon marry

and leave for America

to live a life of freedom

All as if from a straw sucked in,

desire being like Helen’s on

absorbent fleece, or my being

Paris in mythical Troy

A thousand ships her heart

cries out for against foul weather,

in Greece or other foreign land

It’s what we cherish most,

what we will want to know

about best, as I continue to tell…

my heart beating faster

A wooden horse comes along

as she still imagines crossings,

thighs bared, closing in on territories

with a love she will never return.

Discovery

Chewed with these same teeth,

walked with these same legs,

furrowed these very brows

(a Peruvian mummy

discovered:

500 years old)

The shape of things to come

with the moment’s reckoning,

because of times past

Or living with boundaries

that never really

set us apart

Now looking across the horizon,

and what do you see

but vistas mirrored

Climates coming together,

but do not really

as I hark back on reality

Being on edge and reminded

of another place, the vision

compelling us to it

(this one

laid to rest

since time long ago)

Tundra of lost time–

a condor flying over

hills and mountains

A rendezvous of sorts,

life at a standstill…

in the silent imagination.

***

(Short Fiction)

My Father’s Tagore. By Cyril Dabydeen

T

he tarantula moved slowly, deliberately, on the zinc-sheeted tent a few feet above me. Desultorily I looked at it, then turned my gaze once more to my father laid out in his bier in the middle, in the haze of heat—and maybe, I imagined the spider coming closer. Everyone sweltering, the women mourners mostly, and the Pentecostal Christian minister kept it up–the funeral service ongoing. And just when it seemed completely still, the tarantula moved again.

I became riveted to it. The mourners shifted uncomfortably; the men with almost bent bodies stood in the periphery watching, waiting, almost mute-looking. The hefty-looking female minister heaved in again, swaying right and left; her charcoal-hued skin glowed. Instinctively I rubbed my eyes. Did I simply imagine the tarantula?

Distraught-looking everyone was, the villagers; and I’d come for the funeral of my father from wintry Canada. A few mourners looked at me closely, to see how I was taking it. Yes, my father’s death; and the minister’s words kept rising: eulogizing my father with hymn-singing. And words about my father’s life expressed from those who knew him well, I recreated. My brother, Dev, who’d come with me from Canada sat next to me; he was grim-faced. Again I glanced at the casket laid out before us. The heat sweltered, like the hottest time of the year.

Scents, perfume sprinkled on my father’s bier as part of the ceremony in this his “final” hour; and the willing-unwilling mourners fanned themselves. The tarantula moved again. How real?

Right then I expected my father to open his eyes and look up at the spider. Did I want him to flick the spider away so it wouldn’t fall on me… or, on him? The spider’s bulbous eyes it seemed; and in an odd way I was becoming re-acquainted with the tropics having been away for so long. Were there more deadly tarantulas around?

What else I remembered? My father also remembered.

The Bible-thumping minister, Mrs Hinds, kept lamenting the “dearly departed” as she quoted from the Bible and intently looked at the bier, then yes, she looked at me. Thinking…what? Everyone’s eyes followed the minister’s, it seemed. The mourners concentrated, East Indian villagers mostly, heads bowed; and “sinners” we were, said the minister in a falsetto voice, becoming more eloquent. And images of my forebears with me, in this “far place,” yes. Mrs Hinds exhorted us to believe, to become good Christians, so we would all be “saved.”

My father saved, too?

Right then I wanted it to be cold, with ice and snow. Canada was with me, I mustn’t forget.

The tarantula, where was it now, as I shifted in my seat?

Unconsciously I kept rehearsing in my mind details of my father’s life: how he’d been pining away, the relatives had said; and the last time I’d come home, more than a year ago, and yes, some villagers had said they were glad I was able to feel his pain as the end was drawing near.

What I must truly know.

My father’s grown children, his daughters mostly, shifted about, some in tears. His wife–a round woman–whom he’d married about ten years after he and my mother grew apart, stirred uncomfortably; she’d whispered to me, “He done dead”–in her fateful manner, and lachrymose she became. The bier was indeed before us, as the Christian-pentecostal minister continued on.

The solemn-looking men-mourners watched intensely as the minister harangued about who would be “saved”—these villagers who were mostly diehard Hindus, and some Muslims. One or two stirred, as I looked at them. And I instinctively looked up again, hoping to see the spider amidst strands of twisted foliage fastened to the tent. Camouflaged it was. The Christian minister focussed on her “message,” bent on converting us all. “Amen,” I involuntarily let out.

The tent’s frame shook, the bamboo and zinc sheets piled with interlacing thrash. The microphone also shook in Mrs Hinds’s hand.

Did no one else see the tarantula? Would it fall upon some hapless victim…on one of the women mourners seated all around, perhaps?

But not on my father lying in his open casket. Christ!

Mrs Hind grew edgy, as she raised her voice again. She wiped perspiration from her neck, hands, with a soiled handkerchief. The men mourners a few hundred yards away, my father’s cohorts–who knew him in his sometimes unpredictable way, and who lived in the adjoining houses among the palm and jamoon trees…they really mourned him.

Mrs Hinds wiped more perspiration from her forehead, neck.

Determined she was in her evangelical zeal.

My brother Dev, a silent witness indeed, kept brooding.

What was he thinking? Did the minister…know? Know what?

Yes, I was glad my father wasn’t suffering in the heat…now being deceased. Cologne reeked from the bier, mixed with the scent of talcum powder. More relatives wept, some seeming to look intently at my father laid out in white shirt and tie and with a dark jacket and dark slacks…clothes he’d never worn before. Odd, I pictured him being fancifully ready to attend a ball as in Victorian times, here in our former British colony.

Dev nudged me–what was I really thinking? I nodded back to him.

He made a face, one of doubt it seemed. Recurring thoughts, fleeting, momentary. Odd, I listened earnestly to the minister’s words, her homily. She directed her gaze to me again because, well…my brother and I had come from Canada.

Then on me…alone.

Other relatives also focussed on us, everyone observing how I was taking my father’s death–I, his eldest son…who’d been away so long.

The minister’s chosen words from the Bible as she again looked at me My turn….the eulogy I must give? Did I not know? She tilted her head towards me. Odd, I looked up again…for the tarantula. The men all around wavered, more anxious, it seemed.

Who…or what else wavered?

The minister brandished her Bible before me.

Dev nudged me hard. Unconsciously I thought we were now in an actual Indian village–here close to the equator, in South America–where it’d once been called El Dorado. Not in the faraway Ganges?

Death and resurrection in the Christian way, I yet contemplated. Then Mrs Hinds handed the Bible to me, for me to read a chosen passage. The tarantula moved again; but I shifted my gaze to the onlookers, mourners; and yes, the humidity sapped our energy, mine most of all.

I took the Bible from the Minister’s hand. The men mourners all around quickly leaned forward, some moving close up, muttering among themselves inaudibly; their mouths opened and closed, swallowing the dry air. Some braced against the rickety fence near the palm and mango trees…and, they were indeed paying their last respects to my father, yes.

“He done dead,” I heard someone echo.

More women wept openly. The minister beckoned again: I must now read a passage from the Old Testament marked out for me, then a passage from the New Testament: Acts, Paul of the Apostles.

I wiped my brows.

The minister wiped hers, too; from the nearby town she’d come determined to “save souls”. Dev nudged me once more, urging me to be aware of what to read. Did the tarantula move again? Ah, one bite….

And a hospital was more than six miles away—but by first going through a winding pot-holed road to the nearby town. But salvation was at hand, everything being played out in my father’s passing in this his “final hour”. The minister’s mahogany skin burnished. “Amen,” I heard.

“Amen,” I involuntarily let out back.

“Amen-amen!” a collective cry rose.

My father lipping the words too?

My throat itched, my voice becoming hoarse as I read.

Everything became blurry; and the men around fidgeted uncomfortably. My father fidgeted too, did he? He was not pious, not a Christian the way his wife and daughters were, all who became converts; and my father might have just humoured his wife’s “faith,” teasing her about it. He did. “You must believe, man?” his wife had rebuked him.

“Believe, wha’ for?”

“You…goin’ to be dead soon,” she chided with dark humour.

“I am a’ready dead. Heh-heh!”

More laughter.

“You not really dead yet, eh? But, only when Jesus come fo you!” his wife berated.

“Jesus?”

My eyes rivetted to the tarantula once more.

My brother Dev grew more uncomfortable, in the sun’s silence, the humidity palpable. And the women mourners appeared prayerful. The men, too, the same who might have mocked my father about his family members becoming converted and were now “Christians.”

“Wha’ for, Gee?” one older man asked.

My father’s nickname, Gee; he smiled.

“Hindus we are, eh?” another asked.

“What’s Hindu, being far from India?” my father hissed.

Maybe it didn’t matter if our forebears had come from Bihar or Uttar Pradesh, as generations inexorably passed.

But now Gee was really dead, and the men, the neighbours, contemplated their own fate no doubt.

An entire church choir it seemed now; my father’s wife and daughters gathered closer–as Mrs Hinds exhorted them to do, same as she regularly did in church in the nearby town. Ah, the tarantula, where was it now? Still camouflaged amongst bamboo foliage? See, I wanted everyone to be aware of it. Urgency in me now.

But the minister was winding down her “service,” but with more prayers said.

Distinct sobs, I heard. The men becoming more restless.

What Gee, my father, perhaps never felt. Indeed he kept his Hindu faith deep in him, I presumed to know. What was deep in us all, yes.

Mrs Hinds tightened her lips. Now I would say a few words…as part of the eulogy–for custom demanded it; and, I was indeed from Canada with eloquent English skills they imagined. The village men drew much closer. The Ganges, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, all came closer. What Dev sensed. But I had no prepared text or speech.

Maybe I would talk about the gritty life my father lived. A tremor I felt. The tarantula seemed more camouflaged. My father in his bier, being itchy I figured. Long seconds passed.

I whirred. Then Dev handed me a text, which he brought with him, something retrieved from Internet back, yes. The text: Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali, which I’d reflected upon in my youth; and words I might have memorized, since then.

Mrs Hinds let out a soft growl. Did she? Turmoil…everyone sensed. My heart quickened. I flitted across continents, India, all of Asia, then back to Guyana–here close to the equator. And the words I started reading. Waves beating, on a far shore.

Breathless I became… indeed seeing my father clearly, the life he actually lived. I tilted my head again, unconsciously looking for the tarantula. But, I concentrated…on Gitanjali, a particular verse, “Farewell,” like my own last words:

I have got my leave. Bid me farewell, my brothers!

I bow to you all and take my departure.

Here I give back the keys of my door

—and I give up all claims to my house.

I only ask for last kind words from you.

We were neighbours for long,

but I received more than I could give.

Now the day has dawned

and the lamp that lit my dark corner is out.

A summons has come and I am ready for my journey.

Halting I was, with more echoes of India as I kept on reading–like I was hearing my father’s own last words: Tagore’s words became resonant. Everyone nodded…to me, and I nodded back. Then some of the men waved, and odd, it seemed like the entire village waving.

The village women came closer. My father’s round wife forced a smile. Mrs Hinds deliberately wiped perspiration from her face. My personal farewell it was… this eulogy. Dev’s too it was.

And there would be no applause. Here: our being at the centre of the world in the Amazon–where my father had lived his indeterminate life, I knew. An image of my mother, too…when she and my father had lived their gritty existence. Then the tarantula pushed its head out, antlers and all.

But nothing else mattered. I read on, voicelessly, my heart racing.

Tagore’s words: like my father’s own. The village women fluttered their white handkerchiefs; the men wavered again…now with their special applause, a sound like that of falling rain. Tropical downpour, see. My father’s farewell…and life’s beginning and ending. I watched the spider move out into the open—almost like what Mrs Hinds might have contrived, casting her spell upon us, it seemed.

Ancestry all around…India and Africa, here like the most forgotten place in the world. Illusory, but real. “Rock of Ages”: the hymn everyone now sang. Hallelujah! Canada’s cold and ice I conjured again, in the unbearable tropical heat. Dev kept up his own pose, because of what he believed; and I also believed.

Tagore’s words with a new resonance, and we grew closer.

Mrs Hinds, well, she made a face–because she too saw the tarantula for real. Nothing misbegotten, do you know? New spaces, nothing less–and time passing by.

********

Notes Cover image courtesy https://tt.loopnews.com/content/indo-trinidadian-experience-display-divali-nagar-art-gallery

![]()

Cyril Dabydeen-- “a noted Canadian poet” (House of Commons, Ottawa), short story writer, novelist, and anthologist. His latest of 20 books include My Undiscovered Country/Stories, God’s Spider (Peepal Tree Press, UK), My Multi-Ethnic Friends/ Stories, and Imaginary Origins: New and Selected Poems (PTP). His novel, Drums of My Flesh, is a Guyana Prize winner, and was nominated for the IMPAC Dublin Prize. Cyril’s work has appeared in over sixty literary anthologies, e.g, Poetry, The Critical Quarterly, Canadian Literature, and the Oxford, Penguin, and Heinemann Books of Caribbean Verse. He’s included in Singing in the Dark: An Anthology of Lockdown Poems (Penguin/Random House, 2020). He juried for Canada’s Governor General’s Award (poetry) and the Neustadt International Prize for Literature (U/Oklahoma). He taught Writing at the University of Ottawa for many years. He is Guyana-born, of Indian origin.

It is absolutely a joy to read Cyril Dabydeen’s writings! He awakes an inherent interest for places and spaces, invoking one’s imagination to see beyond what most might miss. Cyril’s poetry is real and surreal, deeply emotional and tugs at one’s heart and soul!