Representational Image: Towards a new politics?

Shweta Khilnani

Prelude

On 16 December 2012, a 23-year-old female resident of New Delhi, the capital of India, was brutally raped and fatally assaulted in a moving bus by a group of young men. This incident provoked public outcry and furore as people took to the streets to oppose the pathetic condition of women’s safety in Indian urban spaces. There were large processions and demonstrations in front of the legislative house as people demanded more stringent laws and better policing. At the same time, this incident also led to significant changes in the nature of cultural discourse in the country as issues like gender stereotypes, victim blaming, and women’s sexuality were discussed openly in the public sphere. Conversations about patriarchal culture and misogyny as an everyday experience became a part of different mediascapes. On the one hand, young citizens of the country made their presence felt in physical, material settings; while on the other hand, the discontent made its way to online platforms in different ways. Besides being used for orchestrating protests and demonstrations, platforms like Facebook and Twitter were also used to voice personal opinions and share everyday experiences of gender inequality. It resulted in the creation of an ever-growing body of digital narratives which were written by common people about everyday experiences of gender inequality, a phenomenon wherein the personal truly became political.

Shortness, sparseness, and digital literary narratives

T

erribly Tiny Tales or TTT is a popular Indian microblogging platform established in 2013. TTT features stories under 2,000 characters and claims to have an audience of 20 million people. The brevity of the stories attempts to target contemporary digital natives with ‘dwindling attention spans’, as the content posted is ‘quick to read, but hard to forget’, as stated on their official website/app.1 In initial stages, all stories on TTT were written by a small group of 12 writers. However, within a few years of their inception, TTT began accepting entries from the public. Typically, these entries go through a selection process before being published online. TTT has a strong online presence across different social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. On a platform such as Instagram, this produces a grid of multiple posts which can be read at a glance or scrolled through in a quick minute. The conditions of reception and consumption of these posts, facilitated by the mechanics of online platforms, are central to the meaning generated by them and the potential for solidarity thus produced. It also has a significant impact on the very process of writing of these narratives, as their creators make a conscious effort to comply to the attributes of the digital medium. This will become abundantly clear in the following section which seeks to delineate the literary aesthetic of such narratives and the way it interacts with the materiality of digital networks.

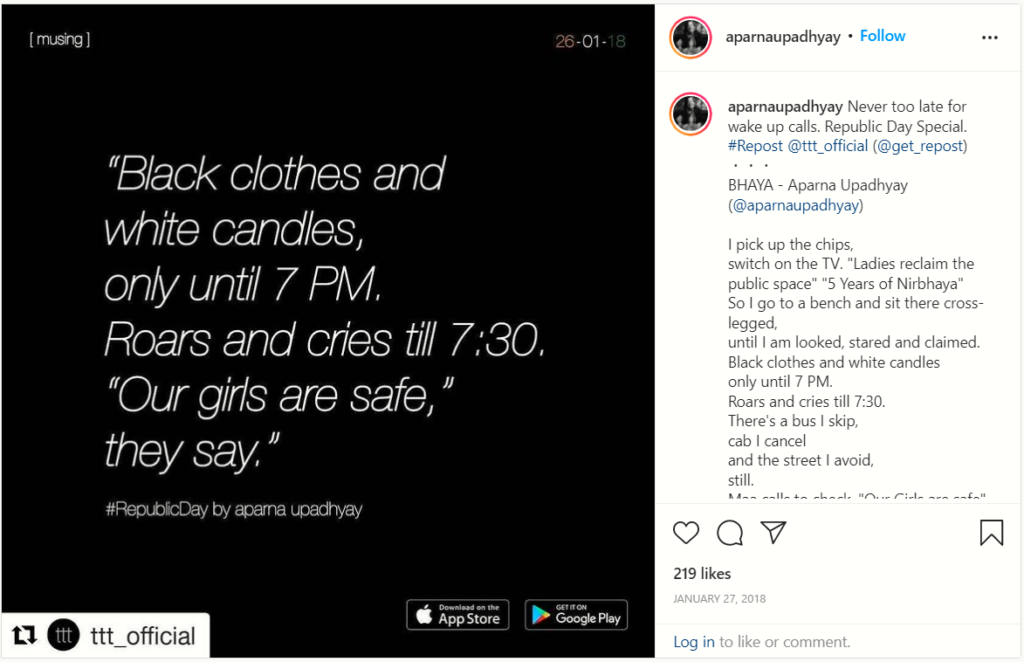

Some of the narratives from TTT shown below directly respond to the rape case of 2012, which came to be known as the ‘Nirbhaya’ rape case due to a general practice in India wherein the name of the victim is not released in the public domain. Several epithets were used to refer to her including India’s Daughter or Nirbhaya, which roughly translates to ‘the fearless one’, before her real identity was eventually disclosed. The following narrative titled ‘Bhaya’ (Figure 1), published on TTT in 2018 almost six years after the rape case, comments on the gap between the claims made by politicians about women’s safety in public places and the stark reality experienced by women in their daily lives. The contrast is demonstrated through commentaries being made on television news shows by people in positions of power and the real experience of a young woman in an urban space in the country. It ends on a sombre note, ‘There is unrest in peace’, even as the news shows find something else to focus on. The title itself ‘Bhaya’, which translates as ‘fear’ in English, is a satirical reference to the most popular epithet ‘Nirbhaya’ which was used for Jyoti Singh, the rape victim of the 2012 case. Since ‘Nirbhaya’ is the antonym of ‘Bhaya’ in Hindi, the title seems to suggest that even as the country was quick to valorise the victim, fear continues to permeate women’s lives in the country.

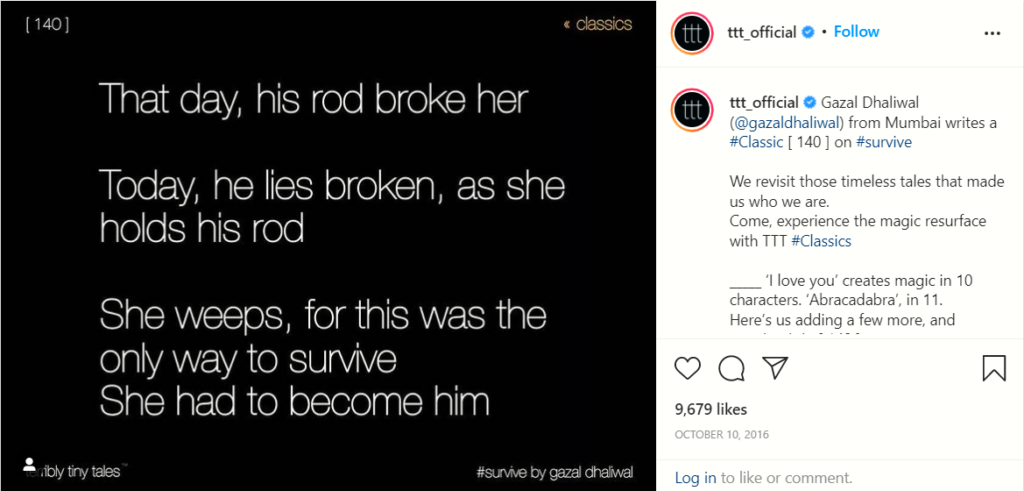

Besides this narrative which has clear allusions to the rape case, there are many others which comment on sexual violence or exploitation in general. For instance, in the following post from 2016 (Figure 2), the rod becomes a symbol of violence and aggression. It is not an exaggeration to state that this would remind the audience of the atrocious nature of the rape case from 2012, since metal rods were used to violate the victim’s body. This post inverts stereotypical roles as the woman is forced to resort to violence in order to defend herself. Ultimately, it becomes a comment on the propagation of violence in different forms and the inability to rid oneself of such aggression.

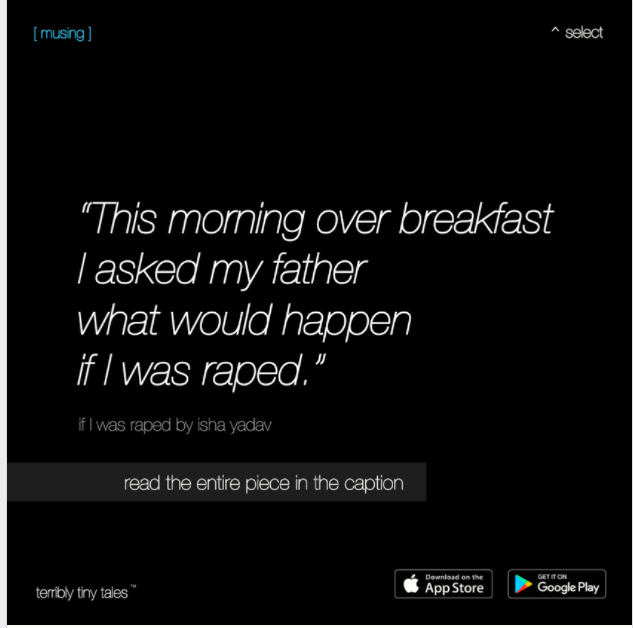

While the 2012 rape case became a watershed moment in the history of gender relations in the country, a number of posts on TTT articulate the incident at a remarkably personal and intimate level. A poem titled ‘If I Was Raped’ by Isha Yadav begins with a young daughter presenting the horrifying prospect of her rape to her father over breakfast. The poem counterposes the banality of everyday experiences like eating breakfast or reading about the ‘urban legend’ of rape in newspapers against the heinous thought of a young woman entertaining the prospect of her being raped.

In yet another poem titled ‘Trepidations for Women’ (Figure 5), Yadav articulates the constant state of fear that marks all her experiences and activities, right from the roads she walks on to the clothes she decides to wear. Both of these poems provide an experiential account of the lived reality of women’s lives. While the former poem does so by entertaining an alarming hypothetical situation, the latter enumerates how the fear of being raped informs every sphere of the speaker’s lived experience. Interestingly, the poet’s imaginary consciousness and their lived reality are equally haunted by the plausibility of sexual violence.

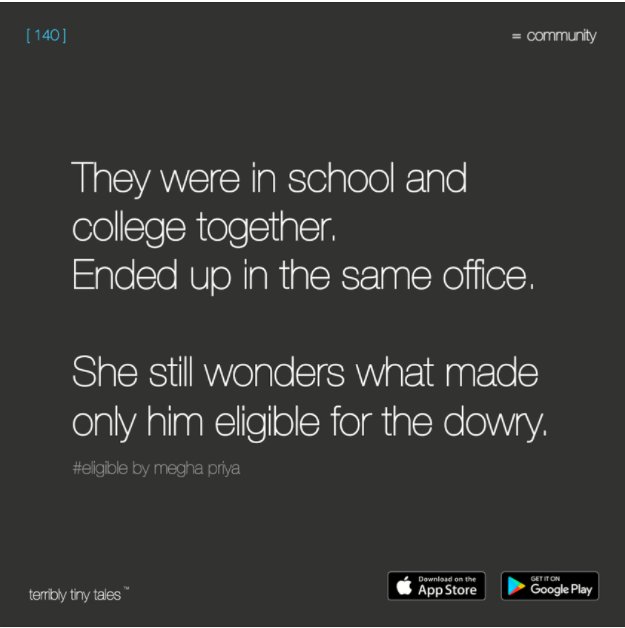

There are several posts which comment on misogyny as an everyday practice within the patriarchal Indian set-up. For instance, Megha Priya comments on the cultural practice of marital dowry wherein the bride’s family is expected to give inordinate amounts of money to the groom’s family during a wedding (Figure 6). Priya questions the logic behind this age-old practice which continues to be prevalent in contemporary times by asking why only men are considered ‘eligible’ for dowry even when a man and a woman have similar merits and achievements.

This curated selection of posts from the microblogging platform helps to introduce some of the predominant tropes related to gender and sexuality which have found representation in online spaces. Given that the 2012 rape case led to a definitive change in the nature of public debate and discourse, one can find many references to it in the narratives. At the same time, even when it is not addressed directly, its lasting influence can be felt in the presence of multiple narratives that speak about gender issues at a personal, intimate level. The choice of words and the tone and tenor of the narratives signal towards an emerging form of personal and political consciousness, one where the ordinary and banal assume the central position. In order to appreciate this dimension of micro-narratives such as the ones featured on TTT, it is imperative to study their literary aesthetic and form. Owing to the digital platforms where these narratives are circulated and received, they are characterised by their minimalism, brevity, and simplicity. They are, quite obviously, designed for quick reading by people who are casually ‘browsing’ the internet on a smart device. Therefore, in order to truly contextualise them, one has to study their literary aesthetic vis-à-vis the ecosystem where they are shared and read by people. This amounts to delineating a digital poetics of such narratives which are produced, disseminated, and consumed within a technologically mediated space.

One of the most prominent dimensions of micro-narratives which is informed by the affordances of new media platforms is their short length. Twitter restricts its posts to 240 characters while TTT, the platform being discussed here, allows a maximum of 2,000 characters. Besides these platform-specific limitations, the very ethos of digital media promotes quick consumption, a phenomenon which is also in line with short attention spans of the audience. As a result, stories are now being told in their miniature form and the constituent elements of storytelling including plot, character, and action are also being modified to scale. This produces a curious digital aesthetic of shortness with frugality as its watchword. Not only should the narrative be small and designed for effortless reading, it must also be able to convey its central message and leave an impact on the reader. While discussing the short story as a literary form, Norman Friedman argues that the nature of action can be inherently small, or alternatively, a larger action can still be captured within a short story.2

What is significant is the economy of the narrative or what the author believes is absolutely relevant for the efficient representation of action. This need to economise the narrative is felt more strongly in the case of microfiction or the very short story which is both more petite and more contemporary than the short story.

In the case of digital narratives, this economy is additionally informed by the movement from page to screen and concomitant shifts in structures of communication.

As a result of this parsimonious approach to writing microfiction, it is stripped bare of anything that is not essential to its composition or aesthetic, resulting in a narrative which corresponds to Marc Botha’s concept of the ‘minimum sublime’.3 According to Botha, microfiction is able to convey a sense of immediacy through a systemic manipulation of scale; as the scale of the work decreases, its intensity increases. In other words, as the text becomes increasingly sparse due to the culling of extraneous elements, it is reduced to ‘the very heart of its aesthetic’. The rawness of such narratives, which is often why they are disparaged as literary texts, is directly responsible for their emotional appeal. One can argue that extreme sparseness of language and form accentuates the intensity of the work.

In the spirit of brevity, the narrative is stripped off of all extraneous details, and whatever remains serves to amplify the effect on the reader. Consequently, their intensity increases manifold, to an extent that they are able to provide a sublimity of reading experience.

The narratives posted on TTT, discussed above, exemplify this phenomenon. For instance, in Dhaliwal’s narrative, the characters involved are simply ‘he’ and ‘she’ and a long, painful history of domestic or sexual violence is condensed into a few sentences by offering an analogy between the past and the present. The past is consolidated into the phrase ‘that day’ and the present is reflected by ‘today’ while the pathos of the proliferation of violence is articulated by the wielding of the rod. Similarly, Priya’s narrative also summarises the entire lives of its characters from childhood to adulthood, symbolised by ‘school’ and ‘office’ respectively within the span of a few words. The attempt here is to convey only what is absolutely essential to the text’s meaning; in this case, that includes impressing on the reader that the two characters had similar levels of academic and professional achievements, yet social norms differentiate between them on the basis of their gender.

The central action of digital narratives is often borrowed from the daily lived experiences of people’s lives. In the examples stated above, the narratives capture events like travelling via public forms of transport, sitting in a park, deciding what to wear to work, etc., all characteristically mundane and unassuming in nature. Even when a seemingly unrealistic hypothetical is introduced in ‘If I was Raped’, the possible modes of the father’s responses to the incident are quite foreseeable, especially within the local cultural milieu. He considers which helpline or ‘neta’ (minister/politician) he would call (a reference to the practice of approaching people in positions of political power to extract favours in situations of crisis) or how he ‘will escape the scandals and gimmicks’ (once again, a culture allusion to the practice of victim blaming in Indian society, where the victim and their family often face social ostracisation). Moreover, the very thrust of the poem is to deconstruct the idea that a father’s daughter being raped is an unlikely event given the sorry situation of women’s safety in Indian cities. Therefore, the experiences and thoughts which find place in these narratives are coloured in ordinariness. They are usual, run-of-the-mill instances which evoke relatability from the readers.

At the same time, the form of representation is also equally bare and unembellished. To a certain extent, this is a function of the economy of micro-narratives. Since there is no scope within the text to delineate complex characters or setting, one usually finds generic background and unnamed characters which reflect social types more than specific individuals. The mode of narration is also largely conversational in nature, resembling the kind of language used in daily parlance. Quite often, there is a play on certain words or phrases, or there is a surprise twist towards the end; however, the language used to this end is objective to a large extent. Critics like Jean Burgess argue that it is possible to conceptualise digital storytelling as ‘vernacular creativity’, a set of creative practices that emerge from non-elite social contexts and communicative conventions.4 Within this framework, people use creative tools which are at their disposal and recombine them in novel ways to produce something which is recognisable yet can create an affective impact.5

Reading, reception, and the hashtag

While the literary aesthetic decidedly contributes to their emotional intensity, the mode of their reception also has a decisive impact on their meaning. Digital narratives are most often read on a screen-based device like a smartphone or a laptop/desktop. The manner of reading on such devices is markedly different from a material book. To begin with, the pace of reading is quicker in the case of online platforms as users browse through the content casually. At the same time, such content is easily accessible as these devices are available to a reader at all times. Reading is not a time or space-specific activity in this case; one can read multiple digital short narratives in a manner of a few minutes when they are travelling in public transport or waiting for their turn in a line. This is not to say that it was not possible for people to read a material book under such circumstances; however, it is undeniable that screen-based devices have made it much easier and more commonplace to read in a wider ambit of situations. Owing to such technologically mediated changes, reading has become a rather banal activity divorced from its earlier status as a specialised exercise associated with notions of enrichment or pleasure.

More importantly, this form of reading often takes place in a state of distraction, either when people are taking a break from other more strenuous engagements or when they are not actively doing anything. With respect to digital and print literacies, N. Katherine Hayles makes a distinction between close reading and hyperreading. According to Hayles, close reading is usually associated with literary texts and entails a ‘detailed and precise attention to rhetoric, style, language choice and so forth through a word-by-word examination of a text’s linguistic techniques’.6 As opposed to the prolonged and undivided attention warranted by close reading, hyperreading is more akin to techniques like quick scanning and skimming, sometimes across several texts which might not form a composite whole. Hayles argues that in contemporary digital environments, it ‘enables a reader quickly to construct landscapes of associated research fields and subfields; it shows ranges and possibilities… and it easily juxtaposes many different texts and passages’.7

Such juxtaposition of narratives in digital environments, coupled with the shortness of these narratives and the form of social media platforms, leads to multiple texts/stories being read at once. For instance, the visual aesthetic of TTT on Instagram amounts to a series of black grids with text in white colour. Even at a single glance, the eye apprehends multiple narratives at once. Therefore, digital narratives are seldom read in isolation.

They derive meaning not as standalone entities but rather as a network of interconnected pieces. Writing about literary microfiction, Botha calls it a ‘sociable genre’ and argues that the question of relation of works to one another, works to readers, and readers to one another is at the heart of the microfictional enterprise.8

In digital environments, such juxtaposition of narratives takes place through the now ubiquitous symbol of the hashtag. If there is one element that embodies the networked mechanics of social media platforms or the internet in general, it has to be the hashtag. In the present age, the hashtag is used for a variety of purposes, right from raising awareness about serious issues to curating jokes or memes on Twitter or Instagram. Interestingly, the concept of the hashtag was a user-led innovation on Twitter in 2007 which was later integrated into the platform.9 Since then, its use has spread to all significant social media platforms where it is used as a principle of organising, structuring, and curation of content.

At its most basic level, the hashtag was intended to categorise all content/narratives within certain headings. For instance, all tweets on Twitter or stories on Instagram pertaining to the Black Lives Matter movement were accompanied by the hashtag #blm, #blacklivesmatter, #georgefloyd, etc. All such posts would be grouped together under these hashtags and form a fluid body of content as more narratives will be added every day. By simply clicking on one of the above hashtags, a user can have access to a wide range of posts pertaining to this particular movement.

In politically charged activist movements such as BLM, the hashtag serves as a significant communication tool by aggregating and classifying the vast quantity of information and narratives. However, when not functioning as an active tool of awareness or political activism, the hashtag becomes a means of navigating the expansive and oftentimes labyrinthine field of social media. It connects digital narratives in a web-like structure, thereby informing the manner in which they will be read by users. Even as this process is algorithmic in nature and can become typically random and arbitrary at times, it has an important bearing on the process through which these narratives acquire meaning and impact their readers.

As hashtags aggregate multiple narratives, a single narrative in the form of a tweet or a post becomes a part of a larger whole which is constantly changing, both in terms of its sheer size but also in terms of its dominant discourse. This facilitates a new form of digital storytelling which is segmented and diffused in nature. It is both spatially and temporally distributed, leading to an assemblage of narratives which are loosely connected to each other.

As a result, digital narratives do not simply exist as standalone pieces with clear beginnings and endings; instead, they derive their true potential in assemblages where they exist in relation to other narratives. Such juxtaposition of narrative is also privileged in the mode of reading prevalent in digital environments, identified earlier as hyperreading.

Therefore, a hashtag becomes a means of preserving an event or a theme in digital memory. Everything related to a particular thread of discussion can be aggregated and memorialised in digital space using a hashtag. When someone posts or publishes a narrative in social media and decides to accompany it with a particular hashtag, they exhibit a desire to be a part of the discursive field. It becomes a way for them to respond to the issue at hand, even if it is through a joke, a meme, an aphorism, or a serious insight.

Affect, ambience, and politics

In addition to being an active discursive space which shapes and reflects political and socio-cultural currents, the collection of digital narratives aggregated by a hashtag is also reflective of the dominant feelings or moods associated with certain issues/events. The ensemble of texts produces a distinct sensorium or a way of feeling(s) about something. This is possibly due to the fact that digital narratives like the ones discussed above are characteristically affect-inducing. Their literary aesthetic, narrative economy, principle of sparseness, and conversational/vernacular appeal give them a certain immediacy, as a result of which, digital users are able to relate to them instantly. At the same time, the affordances of networked platforms, including newer forms of storytelling which prioritise the ordinary and the mundane, and novel modes of engagement facilitated by digital platforms, promote narratives which have affective appeal. Not to mention that digital narratives are often read juxtaposed next to one another, as a fluid stream of images in the form of a ‘feed’ on Instagram or as a collage of tweets on Twitter. At the same time, the combination of visual, written, and aural media turns them into a plethora of sensory stimuli. The quick, seamless, and simultaneous reception of this diverse group of texts produces an ambient feeling, like one is surrounded by sensory triggers. In physical terms, it is akin to being spatially engulfed by stimulating texts/images in a museum or exhibition of sorts. In such a scenario, the pieces have a significant bearing on the affective state of the individual/user, producing in them a set of soft feelings or emotions.

The beginning of the twenty-first century witnessed the emergence of the affective turn in critical theory. This was constituted by a renewed interest in affect vis-à-vis the functioning of the political, economic, and cultural. In the book titled The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social, Patricia T. Clough defines affectivity as a ‘substrate of potential bodily responses, often automatic responses, in excess of consciousness’.10 Clough further states ‘affect refers generally to bodily capacities to affect and be affected or the augmentation or diminution of a body’s capacity to act, to engage and to connect’.

Clearly, affect is closely aligned with emotions and sensations, yet several theorists of affect studies have emphasised the need to appreciate fine distinctions between these categories. Brian Massumi defines an emotion or a feeling as a ‘recognized affect, an identified intensity’11 possessed or owned by a subject. However, affect goes beyond and above feeling as a general way of sense-making. It comes before conscious and cognitive feeling and is best explained as an intensity. While it may eventually translate into cognitively recognised emotions, it is not possible to empirically study this phenomenon with certainty.

What is particularly fascinating about affect is that it is found in a realm of potential, which is later contained by the shape it takes in the form of language or feelings. By studying affect, one can hope to comprehend the phenomena through which this liminal intensity is transformed into recognisable social structures.

An exploration of the presence and functioning of affect in networked media can be pivotal in understanding the points at which new political ideas and beliefs are in the nascent stages of their formation. It can help us understand how political idioms assume a certain shape and form within the materiality of digital networks. This is not limited to political ideas alone; such an inquiry is productive to study the rise of distinctly emotional and sentiment-inducing elements in digital media.

Interestingly, such affective structures allow for differing degrees of engagement and involvement. In the case of distinctly political forms of activism in digital spaces like Black Lives Matter or the Occupy Wall Street Movement, which were backed by the physicality of material struggles playing out on the street, online spaces are often used to bolster the movement. Here, there are clearly ideological positions which are carved out through different forms of digital narratives which are obviously political in nature. On the other hand, when it comes to softer socio-cultural phenomena which are being articulated, consciously or unconsciously, through digital narratives, often not backed by a corollary demonstration on the streets, the type of affective involvement is markedly different. In such cases, there is no absolute call for action or no definitive ideological position to be adopted or performed. Instead, they function as affect worlds where a subtle, ambient form of politics is constantly brewing in the background.

Lauren Berlant’s idea of the intimate publics is particularly useful to understand this notion of an affective and ambient form of political engagement. Berlant’s ‘intimate publics’ foregrounds emotional and affective attachments located in fantasies of the common, the everyday and a sense of ordinariness.12 The sense of belonging to this intimate public remains undefined; in Berlant’s words, you do not need to audition for membership in it. Minimally, you need to perform audition, to listen and to be interested in the scene’s visceral impact.

One can infer from this argument that there are different possible degrees of engagement ranging from a casual passer-by who is affected at some level by what they see or hear or read to an involved participant who not only consumes but also produces narratives in some manner.

This points towards the formation of new forms of being political in the present. What does it mean to be politically involved in a time when so many political discourses are being shaped in digital spaces? How do affordances of social media platforms influence the dynamics of solidarity? Is it time to rethink our notions of political engagement? Berlant contends that in the case of intimate publics, politics is ‘something overheard, encountered indirectly and unsystematically through a kind of communication more akin to gossip than to cultivated rationality’.13 Applying this notion to the affective realm of digital spaces, the very associations of the term political are undergoing a paradigm shift.

Politics, once associated with rational thought and premeditated ideological positions, is now articulated through the immediacy of feelings and emotions. Political involvement is no longer exclusively contingent on party membership or conscientious activism.

It can now find representation in the form of a continuous stream of narratives which blend fact with feeling and actual information with experiential accounts. People are more likely to engage in the political realm in the form of soft feelings or moods via the digital sensorium of narratives mediated through hashtags on social media. Additionally, the political is negotiated through the ordinary and the banal and lacks the clarity traditionally linked to political thought.

From being a collection of ideas and principles, politics becomes something that is felt as a sensory force. Additionally, it is not located in obviously political acts or registers; instead, everyday thoughts and activities are imbued with political ramifications.

It would not be too much of an exaggeration to say that we are surrounded by politics, albeit of a more affective kind. It is akin to an ambient phenomenon, something that is always on, playing in the background, lightly impinging on an individual’s senses. Brian Eno, the acclaimed musician who coined the term ‘ambient music’, quite famously defined it as something which is ‘as ignorable as it is interesting’. Eno further states that ambient music can ‘accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular’.14 In digital networks, the ensemble of hybrid forms of storytelling with their distinct affective impetus articulates a different form of politics, in the form of a loose, ever-changing cluster of feelings and lived experiences which is constantly there – it is always on in the background. This has been made possible partly by the ambient infrastructure of digital platforms which allow information and narratives to be shared constantly.

Politics has assumed an ambient dimension as the political is now being negotiated in a state of inattentiveness or distraction through characteristically banal registers of belonging. Instead of having to commit unambiguously to a particular political ideology, individuals can develop a sense of contingent solidarity as they relate to certain feelings or experiences. Besides becoming affective and banal, the political has perhaps truly become the personal within this framework. This paves the way for hitherto unknown kinds of political engagement which are more in tune with the contemporary moment and its dynamics. It has a lot in common with Berlant’s notion of the ‘desire for the political’ as the desire for creating the sense of a more liveable and intimate sociality through more affective registers of belonging.

For Berlant, there is a need to establish new idioms of political belonging which are ‘not situated in gestures of heroic action we associate with the political’ but turn towards ‘deflation, distraction and aleatory wavering in unusual arcs of attentiveness’.15

The micro-narratives posted on TTT produce a distinctly affective environment with their immediacy and emotional appeal. Even when they might not strike one as being overtly political since they might not articulate a traditional politics of gender, they do mediate the issue at a personalised, experiential level. There is an abundance of such micro-narratives which acts as an endless stream of sensory triggers, making people feel and live through the dynamics of gender relations. They exemplify an alternative version of political engagement which is political without the politics. In other words, the brand of politics embodied by such narratives is premised on feelings and sensations evoked by the ordinary and the mundane. The assemblage so produced is diffused; it is amorphous and it is ubiquitous in networked social media. The affordances of such digital networks facilitate a unique literary aesthetic of sparseness, narrative economy, and vernacular linguistic composition. All of this contributes to the distinct affective and emotional appeal of these digital micro-narratives. At the same time, the technologically mediated ecosystem within which these narratives are read has a significant bearing on their semantic and political undertones. The logic of the hashtag, along with the ambient infrastructure, produces a spatially diffused sensorium where the political is articulated through affective registers.

The very parlance of the political undergoes a paradigm shift from the special to the mundane, from thought to feeling and from localised spatiality to ambient atmosphere.

*****

Notes The above is a modified version by the author for The Beacon of her essay that appeared here: NECSUS_European Journal of Media Studies. #Solidarity, Jg. 10 (2021-06-05), Nr. 1, S. 173– DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16273 --Copy edited with stylistic changes only by The Beacon team

References Berlant, L. Cruel optimism. Durham-London: Duke University Press, 2011. _____. The female complaint: The unfinished business of sentimentality in American culture. Durham-London: Duke University Press, 2008. Botha, M. ‘Microfiction’ in The Cambridge companion to the English short story, edited by A. Einhaus. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016: 201-220. Burgess, J. ‘Hearing Ordinary Voices: Cultural Studies, Vernacular Creativity and Digital Storytelling’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2006: 201-214. Clough, P. ‘Introduction’ in The affective turn: Theorizing the social, edited by P. Clough and J. Halley. Durham-London: Duke University Press, 2007: 1-33. Eno, B. ‘Ambient Music’, Ambient 1: Music for Airports. EG, 1979. Friedman, N. ‘What Makes a Short Story Short’, Modern Fiction Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1958: 103-117. Hayles, K. ‘How we Read: Close, Hyper, Machine’, ADE Bulletin, Vol. 150, 2010: 62-79. Massumi, B. Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Durham-London: Duke University Press, 2002.

Footnotes 1. https://terriblytinytales.com/index#fourthSection 2. Friedman 1958, p. 108. 3. Botha 2016, p. 208. 4. Burgess 2006, p. 206. 5. Ibid. 6. Hayles 2010, p. 64. 7. Ibid., p. 66. 8. Botha 2016, p. 211. 9. While the pound symbol (#), now popularly known as the hashtag, was always a part of programming culture, it was first used as a tool of aggregating and following content by Twitter on 2009. It is widely believed that it all began when Chris Messina published a tweet in 2007 where he suggests the use of the # symbol for groups on Twitter. 10. Clough 2007, p. 2. 11. Massumi 2002, p. 61. 12. Berlant 2008, p. 10. 13. Ibid., p. 227. 14. Eno 1979. 15. Berlant 2011, pp. 259-260.

Shweta Khilnani is a PhD scholar at the Department of English, University of Delhi. She also teaches English Literature at SGTB Khalsa College, University of Delhi. Her PhD dissertation focuses on the nexus between the literary, the affective and the political with respect to digital narratives. Among her publications are an co-edited anthology titled Imagining Worlds, Mapping Possibilities: Select Science Fiction Stories (2020) and a forthcoming co-edited anthology titled Science Fiction in India: Parallel Worlds and Postcolonial Paradigms.

Leave a Reply