Cyril Dabydeen

I

T

he Indian presence in Guyana’s coastline on the northeastern tip of South America is perhaps like nowhere else; here it is not unnatural to hear Lata Mangeshkar’s lilting voice on the radio with other haunting rhythms of subcontinental India. Other subcontinental voices resonated, indeed. And in the trinity-peaked island of Trinidad about ninety miles from Guyana where V.S. Naipaul was born in the town of Chaguanas–name derived from an indigenous tribe–it is virtually the same. Rhythms, cadences, now with soca-chutney in the cross-fertilization of ethnicities, peoples, creeds. Growing up in Guyana and wanting to become a writer, I was deeply aware of V.S. Naipaul–he came to me in my teenage years: the “charm” of the early books, and then recognition in his works that led me to new awareness of myself in a colonial setting–where life seemed almost in stasis (in the tropics).

Recall with more self-awareness: like when I’d returned to the Caribbean to attend a special event to honour the poet Kamau Brathwaite at the University of the West Indies (Mona: Kingston, Jamaica), and nascent instincts came to me afresh–as I listened to Brathwaite talk about “ancestors,” and “Africanness.” History’s indelible markers in a world novelist George Lamming had said “every Caribbean writer carries with him the weight of the pressure of history”; and, “A writer like Vidia Naipaul is always preoccupied with what he sees,” Lamming added, which resonated in me.

In my formative years of the 50’s and 60’s, it was what we experienced, existentially, in marginal, or, organic ways. And Naipaul enabled me to fashion an almost new sensibility in the flux of history: archetypes of Europe, Africa and Asia in the mix interspersed with what seemed basic or indigenous. Bhajans (songs)–Bhojpuri-and Hindi-based–were indeed with us amidst calypso and reggae. Then, soca and chutney which in an odd way helped us to confront our indentured labour legacy.

But the literary life I longed for: as I innately yearned for some kind of permanence. I’d read Frantz Fanon and internalized notions of “self-contempt” as he wrote about in psycho-social and political terms. Self-reflexive I became; then, the sense of the “Indian arrival” and what else I became associated with: ritual about the sacred and wanting to establish an enduring life; the “spirit in the place” in a world with cosmopolitanism, and tropes of Empire being in the mix, or in background. Naipaul’s early writings made an immediate impact. His short stories, especially his Miguel Street (l959), were echoic, if in sometimes uncertain ways. I also read his other early books: like The Mystic Masseur (1957) and The Suffrage of Elvira (1958). But A House for Mr Biswas (1961) established his authentic Caribbean voice; my imagination became more alive.

In context: Naipaul’s view that “being an Indian in the Caribbean is an unknown fact” I cogitated upon. A critical consciousness also stirred in me about the “examined life”; I kept engaging with Naipaul in his narrative; more than anything else, it brought home to me the sense of possibilities: as I contemplated Mohun Biswas’s alienation and life in the Tulsi household; yes, Biswas raged against his confined Indian space, circumscribed or demarcated by the small island of Trinidad.

I became more self-aware, and reflexively identified with Naipaul’s early beginnings: he writes: “As a child trying to read, I had felt that two worlds separated me from the books that were offered to me at school and in the libraries; the childhood world of our remembered India, and the more colonial world of our city … What I didn’t know, even after I had written my early books of fiction, concerned only with story and people and getting to the end…these two spheres of darkness had become my subject” (“Reading and Writing: A Personal Account”).

This distilled view is juxtaposed with Naipaul’s expression in Middle Passage (1962): “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.” In The Enigma of Arrival (1987) Naipaul goes on to speak of “the colonial smallness [of Trinidad] that didn’t consort with the grandeur of my ambition….” And, I saw in the Biswas character really as a small man as I contemplated his circumscribed life and his potential for liberation; it was also the artistic spirit coming to grips with my own individualistic ways. Naipaul’s sense of personal and spiritual space, I more seriously reflected upon, even with some foreboding.

“It made for an extraordinary self-centredness. We looked inwards; we lived out our days; the world outside existed in a kind of darkness; we inquired about nothing,” Naipaul adds. He steered readers, ardent those like myself in the direction of not seeing ourselves as communal, parochial or provincial. (Later when I edited Beyond Sangre Grande: Caribbean Writing Today, 2011 this thought was very much in my mind.) But in faraway Guyana in the early years a new stirring, it seemed: the imagination was all as I reconstructed Biswas truly yearning for seeking self-awareness despite his lethargic way of life governed by fate in Hanuman House (Naipaul had more than an inkling of this experience derived from his own father, Seepersad Naipaul).

Cold-eyed V.S Naipaul became in attitude with his integrity intact.

Liberation or escape from a too-limited world view would be echoed many times again; in l979, he said, forthrightly: “I do not write for Indians, who in any case do not read. My work is only possible in a liberal, civilized western country.” I reflected upon this, and subliminally confronted reality around me: in a dire colonial setting with political ideals about transformation tied to my nascent nationalistic impulses. When criticism of Naipaul became almost hysterical (as some Caribbean scholars called for Naipaul’s books to be burnt), I replayed in my mind what the other Trinidadian-born novelist, Sam Selvon–initially London-based, but who later lived in Canada–said to me in his usually unaffected way: “Bhoi, he’s the best thing we have produced,” alluding to Naipaul.

This too stayed with me, despite Naipaul’s utterance: “If you are from Trinidad you want to get away,” as he told Vanity Fair in 1987; and, more trenchantly expressed: “You can’t write if you’re from the bush.” Naipaul’s ironic-cum-satiric stance would be softened by his explanation of what he meant by “the bush”: which no doubt applies to huge swathes of the world, not just Trinidad–and characterized by “the breakdown of institutions, of the contact between man and man. It is theft, corruption, racist incitement.”

Unequivocal he was–I found myself demurring, but not indifferent. Changes inexorably occurred all around, and more I reflected upon. Newness of place and temperament, new attitudes, and being-ness: what I unconsciously accepted, but also denied.

II

I kept dwelling on Naipaul’s attitude to the committed literary life and the sense of forging identity with the spirit bent on seeking out new, if not old, ways of deciphering and decoding meaning or significance in a world riddled with conflicts–while yearning for belonging and permanence–existentialism, yes. But everything kept being seen in vulnerable or predictable ways, maybe in small states everywhere, I contemplated with self-doubt creeping in.

My thoughts see-sawed. I felt a genuine humanity was somewhere possible, even as cosmopolitan London became the compass or prism from which Naipaul assessed the world’s changing ways in the flux of time and what he captured so vividly in his travelogues-turned-monologues. Not surprisingly Naipaul began to change the form of fiction itself: his works formulated as a traveller’s response to all that his senses reacted to, and with everything expressed in his particular style and wit, his unrelenting voice. His perspicuity—I contrived–is seen especially in the later books, on India mainly. Then, it was the Muslim world that he scrutinized in his unwavering or clinical approach tied to the New Journalism, in vogue—and vexatious be became for many.

His intuitive way of feeling and responding to what he saw was perhaps too instinctually driven. In his trope of a bend in the river, Naipaul kept seeing “mimic men” in the settings that were banal, or just anomalous, if only incongruous in his colonial view (as has been argued).

Later, it was seeking out other meanings in a diasporic new world order–he affixed his gaze upon more than imaginary homelands (as Salman Rushdie did); and, troubling enigmas arose, and “mutinies”—if you will: a million or more to be sure. India undergoing massive changes beckoned.

Naipaul’s narratives I yet pondered with my own growing sense and metropolitan awareness with my new or burgeoning Canadian sensibility: I wrestled with Great White North motifs that I assimilated.

But Naipaul’s character Biswas subsisted: as the sense of destiny lingered in the “echo-chamber of the subconscious” (Nadine Gordimer). I also began to see everything nostalgically, or in a forlorn sense, not far unlike what the poet-character B. Wordsworth sees in the eponymous story in the Miguel Street volume; then, too, like the more engaging character named Hat, I began feeling determined to look beyond an island-horizon.

Around this time I wrote my own first novel The Wizard Swami (1990), as images distilled in me (in an earlier version of this novel I’d unconsciously immersed myself in R.K. Narayan’s and Naipaul’s books and crossed boundaries).

I also regularly read other writers from more varied backgrounds during this early period: English and American ones, and African and other writers too, in trying to come to grips with my own vision or impressionistic beliefs. I’d taught Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart to young teacher-trainees in Guyana. Images resurfaced. Tagore’s lyricism also came to me as new and old worlds came closer; and India as a mega-sized country–a subcontinent, truly–dwarfed Trinidad or Guyana; yet I saw in some perspective my forebears’ lives—indentured peoples–in sometimes fresh or new ways–like the growing mind’s imprint, as it were.

I also grappled with my internalized Kiplingesque landscapes with other images of Africa in repudiating imperial vestiges that lingered or were imbedded in me. Gandhi and other stalwarts also came to me, inevitably, as politics seared into our beings amid shifting ideologies and shifting grounds. But hegemonies prevailed. And I yet envisaged Naipaul being sardonically aloof in London because of his special affinity for a different way of life–like a defense mechanism, if being distinctly unlike Evelyn Waugh in temperament.

I kept being self-reflective no less, while confronting my own disappointments and I started to carve out my own imaginative space, I thought. Later, like the Indian writer Amitav Ghosh, I imagined “truths that were too painful to acknowledge; some because they were misanthropic or objectionable.” And indeed, “it was Naipaul who first made it possible for me to think of myself as a writer,” as Ghosh added; and what I also believed about myself-–the indwelling life–as I longed for clarity of ideas and purpose in my sometimes disparate feelings and experiences.

Juxtaposing what I derived from Naipaul’s An Area of Darkness (1964) and India: A Wounded Civilization (1977) with what I learned and then longed for in my own visit India and then to go beyond an exotic land derived from Kipling, and yes, exorcize those images from my consciousness. Individuation I longed for in finding out more—much more–about myself in a wider world.

Indeed, Naipaul revamped his India in A Million Mutinies Now (1990), as everything came together. But then too, narrative became as an end in itself (as Naipaul no doubt conceived it). I came upon a less nostalgic, but symbolic, recognition of the world past and present: the jamoon or the neem tree in India began to be seen as familiar emblems in my growing-up childhood in Guyana, and now in my manhood.

I read Naipaul more critically and balked at his stance, even if it all stemmed from a prevailing enigma. (“The thing about being an Indian, and it remains true of Indian writing now, is that it seems to work without history, in a vacuum,” Naipaul said, with his customary irony.) I began to believe, also, that it was his consciously deliberate way of individual thought about the politics of place and one’s evolution–as former empires inexorably crumbled, and with things indeed falling apart: the centre no longer holding. But did it ever…with Kurtz reappearing?

The writing life indeed set Naipaul apart, if not singularly alone, though he no doubt also longed for community, but simultaneously appeared to have disdained it, and herein lies the paradox: as he ironically wrote books such as Mr Stone and His Knights Companion (1963) which depict British life with verisimilitude to demonstrate his cosmopolitanism, earning praise for this achievement.

This was the true or authentic Naipaul I figured him to be–as I reflect on my own sense of beingness and trying to achieve integrity in a writer’s vocation conscious of narrative having its own raison d’etre. Yes, one’s accepted views would often clash against Naipaul’s unrelenting gaze and scrutiny tinged with his sometimes jaded vision of the world. I wrestle with more as I read and contemplate his oeuvre.

Underlying this too perhaps is the recognition of decay or destitution, as I reflect on Naipaul’s “mimic men” trope or foil with the foibles or idiosyncrasies he characterized in comparable ways as once-promising new worlds truly seem to fall apart (former Rwanda, Congo at times); and as fellow Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott punned: V.S. Naipaul became “V.S. Nightfall,” yet also acknowledging Naipaul’s superb craftsmanship–for Naipaul was above all a master stylist bent on changing the novel’s “bastardized form” (Naipaul called it); though he also acknowledged its fundamental importance:

“Fiction, which had once liberated me and enlightened me, now seemed to be pushing me toward being simpler than I really was,” he wrote.

I kept being aware of history, post-colonial primarily, which Naipaul seemed to have no patience for, but for the individual’s will in enduring without maintaining obvious allegiances. And, the Nobel Prize Committee’s citation of Naipaul’s award would be for his “incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories”–singling out The Enigma of Arrival (1987) for its “unrelenting image of the placid collapse of the old colonial ruling culture and the demise of European neighbourhoods.”

I will keep introspecting about this as being at the heart of creativity itself–the power of narrative shaping one’s vision—or, simply wanting more than anything else to try to make one’s voice endure without telling too much. Philosopher-essayist Hannah Arendt says it best about narrative: “Storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it.”

III

I will continue to regard Naipaul as one of the world’s great writers despite the controversy about his attitude and his sometimes trenchant utterances (“The dot means my head is empty”: about the bindi Hindu women wear; or, on Pakistan: “The Pakistani dream is one day there’ll be a Muslim resurgence and they will lead the prayers in the mosques in Delhi”; or, of Britain: “a country of second-rate people–bum politicians, scruffy writers and crooked aristocrats”). Naipaul’s pragmatism it is, too, as rituals associated with magic and romanticism appear alien to his sensibility, and by extension foreign to worlds of the metropolitan centre he continues to embrace; and no doubt in his travelogues, we will continue to see his objectification, if you like, as his norm.

Not unexpectedly the Muslim fundamentalist world comes in for much of his criticism: in Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey (1981) and Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions Among the Converted Peoples (1998) Naipaul’s oftentimes caustic observation or analysis prompted the late Edward Said to comment: “In the earlier book, its funny moments are at the expense of Muslims, who are ‘wogs’ after all as seen by Naipaul’s British and American readers, potential fanatics and terrorists, who cannot spell, be coherent, sound right to a worldly-wise, somewhat jaded judge from the West.” Yet, Said would acknowledge in his Reith Lectures Naipaul’s role to “challenge routine, assailing mediocrity and cliches….”; and then, writing about Naipaul’s “extraordinary antennae as a novelist” says it attests to the novelist’s “sifting through the debris of colonialism and post-colonialism, remorselessly judging the illusions and cruelties of independent states and the new true believers ….”

Naipaul’s “colonial rage” focuses on both people and the societies they live in: the seeming chaos of India, Africa, the delusion of Islamic fundamentalists, which are telescoped through his unique lens (whether we agree with him or not); and for him freedom implies being at odds with everyone else, especially those who lament the colonial past (as he did at a conference in India, which irked the likes of Salman Rushdie). But more than anything else, Naipaul fully engages us and makes us think hard about our embedded ideological commitments, or paradigms, and as so often occurs, his narrative insights compel us to keep reading him to tap into the intuitive dimensions of his art which may be separate from any facile or easily identifiable social predisposition on his part.

In Canada I’m often swayed by Naipaul’s prose style often touching on the organic: I keep recognizing a bigger world, not least because of my own interest and preoccupation with new possibilities. And Naipaul’s indebtedness to his father, Seepersad Naipaul, does not escape me, the life of going beyond acceptable Hindu ways in small-island Trinidad or coastal Guyana that the writing life initially presented to him—that the letters between father and son attest to in almost poignant ways and showing the complex sensibility at work.

As has sometimes been said—now worth repeating–Naipaul is his own main character in his books (perhaps in the way many Irish writers are). In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he said, “When I became a writer those areas of darkness around me as a child became my subjects. The land; the aborigines; the New World; the colony; the history; India; the Muslim world, to which I also felt myself related; Africa; and then England, where I was doing my writing. That was what I meant when I said that my books stand one on the other, and that I am the sum of my books.” While he favours being in the limbo world of a free state because of his commitment to art, he kept pushing the boundaries of fiction and autobiography, going to the heart of his organic nature– and, as he affirmed Marcel Proust’s axiom about “the secretions of one’s innermost self, written in solitude and for oneself alone that one gives to the public”–as his very own–which I keep contemplating in order to sustain myself as a writer, nothing less.

******

Note An original form of this essay appeared in Transplanted Imaginaries: Literatures of New Climes, ed. Prof. K.T. Sunitha. New Jersey, USA: Africa World Press, 2008. Now revised for this publication.—Cyril Dabydeen

———————-

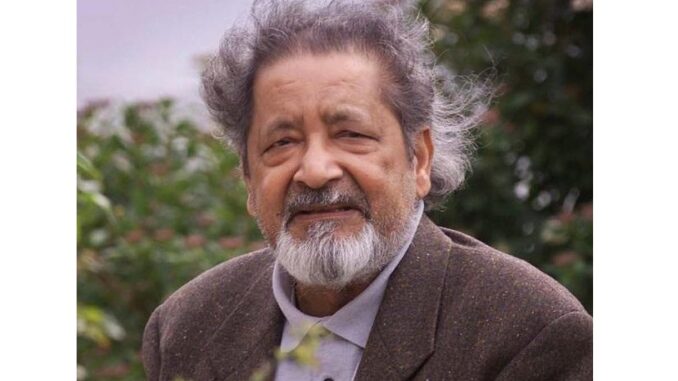

Cyril Dabydeen-- “a noted Canadian poet” (House of Commons, Ottawa), short story writer, novelist, and anthologist. His latest of 20 books include My Undiscovered Country/Stories, God’s Spider (Peepal Tree Press, UK), My Multi-Ethnic Friends/ Stories, and Imaginary Origins: New and Selected Poems (PTP). His novel, Drums of My Flesh, is a Guyana Prize winner, and was nominated for the IMPAC Dublin Prize. Cyril’s work has appeared in over sixty literary anthologies, e.g, Poetry, The Critical Quarterly, Canadian Literature, and the Oxford, Penguin, and Heinemann Books of Caribbean Verse. He’s included in Singing in the Dark: An Anthology of Lockdown Poems (Penguin/Random House, 2020). He juried for Canada’s Governor General’s Award (poetry) and the Neustadt International Prize for Literature (U/Oklahoma). He taught Writing at the University of Ottawa for many years. He is Guyana-born, of Indian origin Contact details: Cyril Dabysdeen@ncf.ca

Leave a Reply