A Word

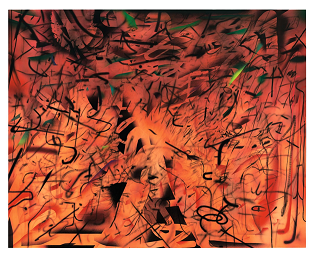

The image above of a painting by Ethiopian-origin American visual artist Julie Mehretu, daughter of immigrants to the US from Addis Ababa, seeks a new language of delirium, both shocked and enraged as it tries to offer witness to a world where not a day goes by, without the most grim acts of religious and ethnic wars, rape, lynching and tormented and bewildered migrants desperate enough to risk beatings and death, concentration camps. It is as if our social and physical world is on fire and there is neither any hope of safety or end to suffering. Looking at the work, I was reminded of a note I had written in 1996 about Manto:

“Manto’s stories about the partition are more realistic and more shocking records of those predatory times [than those of his contemporaries]. They are written by a man who knows that after such ruination there can neither be any forgiveness nor any forgetting.” Of course, Julie’s work is not realistic at all, but then the language of realism no longer seems to be effective. We have all become so emotionally numb at the pile-up of daily atrocities that the news of yet another scream by yet another tormented soul provokes little empathy.—Alok Bhalla

**

Saadat Hasan Manto

{Translated from Urdu by Alok Bhalla)

“BHAIJAN, let me tell you about an incident in 1919 when there were agitations against the Rowlatt Acts throughout Punjab…I am talking about Amritsar…Under the defence of India Act, Sir Michael had prevented Mahatma Gandhi from entering Punjab…Gandhiji was on his way, when he was stopped at the border of Palwal, arrested and sent back to Bombay…I think, Bhaijan, if the British had not committed that blunder, the massacre at Jallianwalla Bagh would not have left such bloody marks on the dark pages of their history…There was a lot of respect for Gandhiji in the heart of every Muslim, every Hindu, every Sikh…When the news of his arrest reached Lahore, all business came to a halt…News spread from Lahore to Amritsar, and there was a spontaneous hartal in the town…It is said that by the evening of ninth April, the Deputy Commissioner had received orders to expel Dr. Satyapal and Dr. Kitchlew; he was not willing to carry out the orders, since, according to him, there was no danger of a violent agitation in Amritsar; there had been a demonstration, but no one had dared to act without the permission of the organisers…But, Bhaijan, that Sir Michael was such a perverse man…He refused to take the Deputy Commissioner’s advice; he was obsessed by the fear that the leaders of Punjab were waiting for a signal from Mahatma Gandhi to overthrow British rule in Punjab, and in fact that was the real intention behind the hartals and the processions…The news of Dr. Satypal and Dr. Kitchlew’s expulsion spread through the city like wild-fire…There was apprehension in every heart; everyone was afraid that some great calamity was about to take place…But, Bhaijan, the excitement was great; the shops were shut; the city was like a graveyard, a graveyard whose silence was ominous. When the people heard the news of Dr.Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal’s arrest, thousands of them decided to go in a procession to meet the Deputy Commissioner Bahadur and plead with him to withdraw the orders expelling their beloved leaders. Unfortunately, Bhaijan, those were not the days when petitions were heard…Sir Michael was like a Pharaoh, instead of listening to their plea, he declared their gathering illegal…Amritsar, that Amritsar which was once the centre of the agitation for freedom, whose body carried the wounds of the martyrdom at Jallianwalla Bagh, is in a bad shape today…Were the British also responsible for what happened in that holy city five years ago…? Perhaps, but to tell you the truth, Bhaijan, I can only see our own hand in the blood that was spilt then…Anyway, Deputy Commissioner Sahib’s bungalow was in the Civil Lines, an exclusive part of the city where every big officer and every big toady used to live…If you’ve been to Amritsar you would remember the bridge which connects the city with the Civil Lines; you have to cross it to reach the cool and shady streets where the rulers had built a paradise on earth for themselves…When the crowd reached Hall Gate it realised that the bridge was guarded by the British mounted police…But the crowd continued to surge forward…Bhaijan, I was in that crowd; I can’t tell you how agitated everyone was, but no one was armed, no one carried even an ordinary stick…Actually, the people had joined the procession only to appeal to the city administration to release Dr. Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal unconditionally…The people continued to move towards the bridge and when they had almost reached it, the British mounted police opened fire…There was a stampede…There were only a few white men, and thousands of people in the procession…But, Bhaijan, bullets have a terror of their own…And, my God, what panic there was; only a few were wounded by the bullets, but many were injured in the stampede. There was a gutter on the right; I was pushed into it…When the firing stopped, I raised my head; I saw that the crowd had scattered…The injured were lying in the street and the horsemen on the bridge were laughing…Bhaijan I can’t describe what I felt at that time; I was completely bewildered…I didn’t know what was happening when I was pushed into the gutter; it was only after I came out of the gutter that I realised the full extent of the tragedy…I heard shouting in the distance, screams, the roar of an enraged crowd…I pulled myself out of the gutter and walked around the Zahira Pir Ka Takia towards Hall Gate…There I saw thirty or forty angry young men throwing stones at the clock on Hall Gate…The glass of the clock shattered and fell on the street…One young man urged the others: “Let’s go and smash the Queen’s statue…” Another shouted: “No…Let’s burn the Kotwali…” The third young man added: “Let’s also burn the banks…” The fourth one, however, stopped them, “Wait…All that’s useless…Let’s go to the bridge and kill the white men…” I recognised the fourth young man…He was Thaila Kanjar. His real name was Mohammed Tufail, but he was popularly known as Thaila Kanjar because he was the son of a tawaif…He was a hooligan; he had become a drunkard and a gambler at a very young age…His two sisters, Shamshad and Almas, were beautiful and enchanting tawaifs in their time; Shamshad had a rich and sensual voice; wealthy men used to come from far to hear her sing…Both sisters were fed up of their brother’s dissolute life; it was well known in the city that both the sisters had almost disowned their brother, but even then he always managed to extort enough from them for his own needs…He was a happy-go-lucky fellow; he ate well, drank a lot. There was a delicacy and a grace about him. He was full of fun and good humour, but he always kept his distance from tricksters and fools. Tall, well-built and strong, he was very handsome…The young men were so agitated that they didn’t listen to him and started towards the statue of the Queen. He called to them once more: “I tell you, don’t waste your energies…follow me…Let’s kill those white men who injured and murdered innocent people…I swear by God that together we can wring their necks…Come on…!” Some of the young men had already reached the Queen’s statue, but others who had held back, stopped, and when Thaila turned and ran toward the bridge, they began to follow him…I thought it was foolish to lead the young men into the jaws of death…I was cowering behind the fountain; I shouted at Thaila from there: “Don’t go yaar…Why do you want to get yourself and these wretches killed…?” Thaila laughed mockingly and replied: “Thaila only wants to prove that he’s not afraid of bullets…!” Then he turned to the young men following him: “If you are afraid, turn back…!” How could they have retreated under those circumstances, especially when one young man had decided to stake his life and attack…? When Thaila charged forward, the young men following him didn’t lag behind…The distance between the Hall Gate and the bridge wasn’t great…perhaps no more than sixty or seventy yards…Thaila was ahead of everyone…There were two horsemen about fifteen or twenty steps away from the parapet of the bridge…Suddenly, Thaila began to shout slogans…As soon as he reached the bridge, there was firing from the other side…I shut my eyes instinctively; I don’t know why, but I was sure that he had fallen. Fearing the worst when I opened my eyes, I saw that he was still running…but he was looking back…As soon as the firing had begun, the other young men had fled; he was calling out to them: “Don’t run away…follow me…!” While he was still looking in my direction, there was another round of firing…He clutched his back and turned around to face the white men…His back was towards me; I saw that his white cotton shirt was splattered with blood…He charged forward like a wounded lion and leapt at the first white horseman…There was more firing…I don’t know what happened in the scuffle, but the saddle of one horse was empty; one white man was on the ground, and Thaila was sitting astride on his chest…At first, the other horseman was bewildered by Thaila’s speed, but he soon regained control over his wildly-rearing horse, and began firing rapidly…I don’t know what happened after that…I was still crouched behind the fountain…I fainted…Bhaijan, when I regained consciousness, I found myself in my own house…A few of my acquaintances had carried me back from the fountain…They told me that the news of the firing had so enraged the people of the city that they had set fire to the Town Hall and three banks, and had killed five or six white men…There had also been a lot of looting…The British officers were not worried about the arson and the looting…The massacre at Jallianwalla Bagh was in revenge for the five or six men killed…The Deputy Commissioner Sahib handed over the law and order of the city to General Dyer…On April twelfth, General Sahib ordered his troops to march through the bazaars of the city and arrest dozens of innocent people…On April thirteenth nearly twenty-five thousand people gathered at Jallianwalla Bagh to celebrate Baisakhi…General Dyer reached the place with Sikh and Gurkha soldiers, and ordered them to fire at random on unarmed people…It hadn’t been possible to make a proper estimate of the wounded and the dead immediately after the event, but a later inquiry revealed that about a thousand people had died and more than three thousand had been injured…But I was talking about Thaila Kanjar…Bhaijan, I have already told you what I saw with my own eyes…Only God is without any faults; poor dead Thaila had committed many sins; he was the son of a prostitute, but he was generous and courageous…I can confidently tell you that Thaila was hit by the very first bullet fired by that white swine; but in his excitement, he didn’t even notice the warm blood flowing down his chest; as soon as he heard the first shot, he turned around to encourage the young men who were running away…The second bullet hit his back and the third his chest…I didn’t see it myself, but I heard that his hands had gripped the white man’s neck so tightly that it had been difficult to separate the two corpses…The white man had already been dispatched to hell…The next day, Thaila’s body, riddled with bullets, was handed over to his family for burial…I think by the time the second horseman had emptied his pistol into Thaila’s body, his soul had already left its earthly prison; that satanic bastard had used Thaila’s body as target practice…I was told that when the body was carried through the neighbourhood there was an outcry…He wasn’t much liked in his community, but when the people saw his body riddled by bullets they began to wail, his sisters, Shamshad and Almas fainted; and when his coffin was lifted, the wailing of his sisters was so heartrending that everyone wept tears of blood…Bhaijan, I have read somewhere that during the French Revolution the first bullet had hit a prostitute…Thaila, that is Mohammed Tufail, was the son of a prostitute. No one has bothered to find out if the bullet which hit Thaila during the freedom struggle was the first bullet or the tenth or the fiftieth, perhaps because the poor boy had no social status; I am sure that Thaila’s name is not even listed amongst those killed in Punjab during those bloody days; but then, who knows if a list of martyrs was ever made…They were terrifying days; the army was in control of the government; that demon, called Marshall Law, roamed the streets hungrily, searching every corner for its prey…During those awful days, poor Thaila was given a hurried burial by his friends, as if his death was a sign of guilt which they were keen to erase…Well, Bhaijan, that’s all; Thaila was dead, Thaila was buried and…and…”

For the first time, my fellow-traveller stopped in mid-sentence and then fell silent.

The train rattled on — I felt as if the wheels on the tracks had begun to chant: “Thaila was dead, Thaila was buried…Thaila was dead, Thaila was buried…” As if there had been no time lag between his death and burial; as if the moment he died, he was buried — the rattling of the wheels was so profoundly mingled with those words that I had to force my mind to break free of their hypnotic rhythm.

I said to my fellow-traveller: “You were going to say something more!’

Startled, he looked at me: “Yes…There is a painful part of the story left to be told.”

I asked: “What?”

He began: “I have already mentioned that Thaila had two beautiful sisters, Shamshad and Almas…Shamshad was tall; sharp-featured; dreamy-eyed…she sang the thumri exquisitely; it is said that she had been trained by Khan Sahib Fateh Ali Khan…Almas didn’t have a good voice, but she was incomparably beautiful; when she danced every part of her body danced; every gesture she made inflicted a wound; her eyes had that magic which could cast a spell on everyone…”

My fellow-traveller spent more time in praising the beauty and grace of Thaila’s sisters than was necessary, but I didn’t think it was courteous to interrupt him.

After a long digression, he returned to the painful part of his narrative: “The story, Bhaijan, is that soon after the tragedy, some self-seeking toady told a white officer about the beauty of the two sisters…Amongst the five or six of the British killed, there was also a woman…What was the name of that bitch…Yes, Miss Sherwood…So, the white officers decided to send for the two sisters and…and enjoy themselves to their heart’s content…You understand, don’t you, Bhaijan…?”

I replied: “Yes!”

My fellow-traveller sighed: “When it comes to death and grief, even dancing girls and prostitutes are mothers and sisters…Bhaijan, I think this country has no sense of shame or dignity…When the Thanedar of the district got orders from above, he obeyed them at once…He went himself to inform Shamshad and Almas that the Sahiblog had sent for them, and wanted to hear them sing and dance…Their brother’s grave was still fresh, that poor boy had been in Allah’s house only two days when…when the sisters were ordered to perform for the officers…Can there be a greater example of injustice?…I think it’ll be difficult to find anything more callousness than that…It never occurred to those who sent for them that even tawaifs have a sense of honour…Do you think they do…?…Of course they do…” He said answering the question addressed to me himself.

I replied: “Yes, of course they do!”

“Yes…After all Thaila was their brother; he hadn’t been killed in a fight in some gambling house; he hadn’t died in a drunken brawl…He had sacrificed his life bravely for his country’s freedom…He was the son of a tawaif, but that tawaif was also a mother…Shamshad and Almas were her daughters…They were dancing-girls, but they were also Thaila’s sisters…They had fainted when they saw Thaila’s body; when his coffin was lifted they wailed so bitterly that everyone wept tears of blood…”

I asked: “Did they go?”

After a pause, my fellow-traveller replied sadly: “Yes…yes, they went gorgeously dressed…” Suddenly his voiced acquired a sharpness: “They went all perfumed and bejewelled…to meet those who had sent for them…Both the sisters looked stunningly beautiful…Dressed resplendently, they looked like fairies from paradise…Liquor flowed, they sang and danced…It is said…that at two at night when a senior officer gave a signal, people left…” My fellow-traveller was silent for a while, then he stood up, leaned out of the window to watch the trees and the electric poles rush past…

The wheels of the train set-up a metallic beat as they repeated his last words: “People left…people left…”

I forced my mind away from the metallic rhythm of the train and asked him: “What happened after that?”

Turning away from the trees and the electric poles rushing past, he said firmly: “They ripped off their glittering dresses, and stark naked, they said, ‘Look at us…We are Thaila’s sisters…Sisters of the martyr whose handsome body you riddled with your bullets only because he loved his country with all his soul…We are his beautiful sisters…Come, pierce our perfumed bodies with the hot irons of your lust…But before you do that let us spit on your faces once…” Then he fell silent and it seemed as if he had come to the end of his story and had nothing more to add.

But I persisted: “What happened after that?”

His eyes filled with tears: “They shot them…”

I was silent.

By then the train had pulled into the station — When it stopped, he called a coolie and asked him to carry his luggage. As he was about to leave, I said: “I suspect you invented the end of the story.”

Startled, he looked at me: “How did you guess?”

I said: “Your voice was firm, but full of anguish…”

My fellow-traveller swallowed hard and said: “Yes…Those damn…” He stopped himself from cursing them: “They blackened the name of their martyred brother…” Then he stepped down onto the platform.

********

Notes --This translation was published in Life and Times of Saadat Hasan Manto, edited by Alok Bhalla (Shimla: Institute of Advanced Study, 1997). The volume is now out of print. --The Beacon wishes to thank Alok Bhalla for making available this translation.

Alok Bhalla is at present, a visiting professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia. He is the author of Stories About the Partition of India (3 Vols.). He has also translated Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug, Intizar Husain’s A Chronicle of the Peacocks (both from OUP) and Ram Kumar’s The Sea and Other Stories into English.

Alok Bhalla in The Beacon A Prayer For My Daughters: Alok Bhalla WHEN KABIR SAW, HE WEPT… Ahimsa in the City of the Mind: Language, Identity-Politics and Partitions Stand by Me: Song of a Farmer The Self As Stranger I Am A Hindu

Leave a Reply