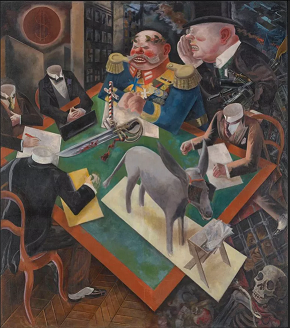

George Grosz. Eclipse of the Sun 1926. Courtesy: The Hecksher Musuem of Art

Alok Bhalla

1

MANTO’s first set of stories about the partition, like “Toba Tek Singh,” “Thanda Gosht” or “Siyah Hashye,” written soon after 1947 are vituperative, slanderous and bitterly ironic. They are terrifying chronicles of the damned which locate themselves in the middle of madness and crime, and promise nothing more than an endless and repeated cycle of random and capricious violence in which anyone can become a beast and everyone can be destroyed. Manto uses them to bear shocked witness to an obscene world in which people become, for no reason at all, predators or victims; a world in which they either decide to participate gleefully in murder or find themselves unable to do anything but scream with pain when they are stabbed and burnt or raped again and again. Manto makes no attempt to offer any historical explanations for the hatred and the carnage. He blames no one, but he also forgives no one. Without sentimentality or illusions, without pious postures or ideological blinkers, he describes a perverse and a corrupt time in which the sustaining norms of a society as it had existed are erased, and no moral or political reason is available.

Manto wrote a second set of stories about the partition between 1951 and 1955. Unfortunately, these stories are neither as well known and documented, nor as systematically analysed as the previous ones. They are, however, significant stories because, together with the earlier ones, they create out of the events that make up the history of our independence movement, an ironic mythos of defeat, humiliation and ruin. If the first set of stories are fragmentary, spasmodic and unremittingly violent, the second set of stories are more complex in their emplotment and more concerned with the deep structural relationship between the carnage of the partition and human actions in the past. While rage and hopelessness still mark the second set of stories, and fear and violence still bracket the beginning and the end of each one of them, the past is more intricately braided into the texture of the main narratives than it is in the first set of stories, and the incidents are more symbolically charged. They should, perhaps, be classified as historical tales which seek to give a “retrospective intelligibility” (Ricoeur, p.157) to the terror of the partition. Each of them tries to locate, at every instance and right down the chronological line from 1947 back to the beginnings of the nationalist struggle, those rifts, breaks and fissures in our social, political and religious selves which always enabled the monstrous to slip into our living spaces.

If the first set of Manto’s stories about the partition are derisive tales of a degenerate society, the second set of stories are both parables of lost reason and demonic parodies of the conventional history of the national movement. The triumphant romance of nationalism, in the official Indian and Pakistani historiography, ends with the victory of a sovereign people (even if they are, themselves, divided by religion) over an illegitimate colonial power, as well as, with the establishment of law governed societies. For Manto, however, 1947 is not a celebrative, an epiphanic, moment. It is, rather, the culmination of a regular and repeated series of actions — I should like to call them “bloody tracks” — which invariably disfigure all the geographical and temporal sites of the nationalist struggle. (I am fully conscious of the melodramatic wildness of the phrase, as well as, its dark opposition to the calmer and more wonder-filled notion of “pilgrim tracks” in the Gandhian discourse on nationalism which led towards the ethically good). As he looks back, after the partition, over the years during which the nationalist struggle was waged, he finds countless examples of characters, ideas and actions which always end in vileness, stupidity and cruelty. Indeed, for him, the “teleological drive” (Ricoeur, p. 157) of the entire nationalist past is towards the carnage of the partition. Unlike other writers who saw the violence of the partition as an aberration in the peaceful and tolerant rhythms of our social and religious life, and so turned to the past for consolation and retrieval of values, Manto refuses to believe that the past was another kind of place and another kind of time (for other stories see my Stories About the Partition of India). The partition, he is convinced, is not an unfortunate rupture in historical time, but a continuation of it. Each of the bloody tracks backwards into time makes him realise that violence is the characteristic of every chronological segment of the history of India from the beginning of the century to 1947; the nasty, the intolerant, the vengeful is always there at every moment; the “doctrine of frightfulness” (Gandhi’s phrase quoted in Draper, p. 211) is not only an aspect of colonial rule, but is also a structural part of the struggle against it. The Gandhian intervention at each instance is merely a temporary and precarious recovery of the ground for virtue, clarity, will and peace. Manto, however, makes it clear that the “punctuated equilibrium” (Stephen Jay Gould’s phrase) that Gandhian politics occasionally succeeds in achieving, is inevitably swept aside and rejected as a sign of weakness, hypocrisy and naiveté. Violence always takes over every significant segment of the nationalist past and transforms India before 1947 into a place which is as strange, pernicious and foul as the present — a place where one can see nothing more than a dance of grotesque masks.

2

THE story, “1919 Ke Ek Baat,” was written in 1951 and published in a volume entitled Yazid. The title of the story demands some attention. The casual inconsequentiality of the phrase “Ek Baat” deliberately confronts our presuppositions about the events which happened in 1919 which, officially sanctioned nationalist historiography assures us, foredoomed the British empire. In all the official and popular historical versions, 1919 is a sinister year which finally revealed to everyone that Britain’s claim to being an enlightened culture was a sham and that its real intention in India was to continue to inflict “racial hatred” on its people. By keeping the date 1919 in the title agnostically unqualified by any modifiers, Manto makes it clear that he has neither chosen the date arbitrarily nor has any interest in displacing our commonly shared assumptions about what the date signifies in the history of British colonialism. Indeed, Manto affirms unambiguously that for him 1919 signifies the loss of the legitimacy of the British rule, by making the narrator say at the very beginning that, had Sir Michael O’Dwyer not lost his head, 1919 would never have become a “blood-stained” moment in the history of colonial India.1 But, the incongruity in the title between the story as being nothing more than an account of a randomly selected incident and the momentousness of the historical events which encircle it, makes one suspect that, while Manto may not be concerned with redrawing the “map of truth” (Kermode, p. 130) of the year 1919, he is interested in offering an impertinent, even scandalous, reading of a well known temporal segment of the nationalist discourse.

Further, the title, when considered along with the date in which the story is told in the text (which is the same as the year in which it was published, i.e. 1951), indicates that Manto is deliberately structuring an entirely fictional event, a “feigned plot” (Ricoeur, p. ix), which pretends to be an authentic eye-witness account of happenings in real time, within two different conjunctions of historical facts. The first frame is, of course, provided by the partition and the entire inventory of dates, names, murders and slogans that gives it its factuality. The crazed presence of the partition, Manto seems to insist, intrudes into any interpretative account of our nationalist history.

The second frame is constructed out of a densely vectored series of events in 1919, like the Rowlatt Acts and the violent protests against them from Bombay and Ahmedabad to Delhi, Lahore and Amritsar, General Dyer’s arrogance and his callous genocide, Gandhian satyagraha and its sad failure to prevent enthusiastic mobs from doing rather “heinous deeds” (Gandhi’s characterisation of mob violence in a letter to J.L. Maffey, Collector of Ahmedabad, on April 14, 1919 but without any knowledge of the shootings at Jallianwalla Bagh the previous day).2

It is evident that Manto’s intention is to persuade us to read the “odd” incident described in his story within the spaces created by those two sets of historical facticities. He invites us, I think, not only to puzzle out the meaning of the bizarre fictional incident narrated by the storyteller without asking about its truthfulness, but also to recognise that there is a profound link between the two historical dates that frame the incident. From his position as a cultural and existential exile in Lahore in 1951, he wants to suggest that, while 1919 doesn’t cause or predict in any mechanical way the horrors of the partition, it contains, what Paul Ricoeur calls, the initial conditions that make them possible; 1919 is merely a part of the sequentiality of events that lead up to 1947. To use Ricoeur again, one could argue that Manto thinks that once 1947 has happened, one can retrospectively find in the fragmentary and disconnected incidents of 1919 — amongst other historically significant dates in the nationalist history explored in other stories — a narrative which could be said to prefigure the brutality of the partition. (Often in history, Ricoeur says, “Action is not the cause of result — the result is part of the action,” p.136). In making such a connection between 1919 and 1947, Manto seems to indicate that his real purpose in recording an incidental story is to pass a “teleological judgement,” not on the British and their indefensible colonial adventure, but on us as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. 1919, as he reads the year from his perspective as a reluctant and confused migrant to Pakistan in 1951, seems to be a part of a chronicle which foretells our doom as a civilisation. It is, as if, Manto is on a historical quest backward in time from 1951, and what he finds on his journey back to 1919 is one of the many “bloody tracks” in our national past.

3

THE story is told five years after the partition by an unnamed narrator to an unidentified listener on a train which moves across unmarked political and geographical space. Given that the story is, as the narrator repeatedly and insistently reminds the listener, being told a few years after the partition, the lack of geographical markers and of national demarcations is as significant as the definite time which frames the entire text. Both the narrator and the listener speak quite specifically about the fate of Amritsar between 1919 and 1951, but Manto’s text itself quite deliberately obliterates the cartographic spaces across which the travellers themselves are moving. What is important here is not the fact of liminality, which is common to all journeys, but the erasure of political boundaries. Fernand Braudel insists that a civilisation is as much a “cultural area,” or a set of achievements and activities within identifiable spaces, as it is an understanding about the modes of living on earth which have slowly accumulated over long durations of time (Cf. On History). Manto’s travellers, who don’t have religious, national or cultural identities, move across a blank geographical space. Given that the journey is being undertaken after 1947 when so much religious and cultural pride was being attached to boundaries, I suspect that by obliterating all signs of territorial demarcations, Manto wants us to understand that maps don’t bestow virtue, that sharply defined religious enclaves don’t ensure the sanctity of moral practices within them and that the separation of communities from each other doesn’t legitimise their cultures. He also wants to render it impossible for any group to make self-righteous claims about its own innocence of intentions or to pretend that its own acts of violence were merely acts of retaliatory revenge. In 1947 it was very clear that many people, irrespective of their claims to a particular nationality, had behaved both foolishly and pitilessly. What they had succeeded in creating were not cultural spaces, but their own kingdoms of death, their own areas of moral void, where there were no distinctions between the religious and the vile, the killers and the victims; their actions had not only dehumanised them, but had also contaminated and humiliated everyone. It is quite appropriate, therefore, that in Manto’s fable the travellers start out, like millions of refugees and migrants during the partition, from somewhere and are carried forward by the sheer momentum of circumstances towards nowhere; their journey itself has neither a locality, a purpose or a meaning.

4

BEFORE trying to make sense of the dismal tale by the narrator, It is worth recalling that the story itself is being written by Manto. In 1951, he is in Lahore. If the narrator is a battered refugee in search of a home, Manto is an anguished migrant who has found a destination but who knows that his days of melancholy will never end. He had lived in Lahore once. But his memories, his companions and his writings belong to other cities — cities which are now in another country. He knows that the cities where he had forged his identity as a writer and as a person have become inaccessible and have changed in unrecognisable ways. The place he has now moved to, Lahore, is not home; it is merely a place to which he has been forced by circumstances to escape to. So is Pakistan, which for him is nothing more than a new name for an old geographical space. Unfortunately, Lahore is incapable of offering him either consolation or hope. The longer he lives there, the more he realises, as his stories like “Shaheed Saz,” “Dekh Kabira Roya,” “Savera,” “Jo Kal Aankh Meri Khuli,” or “Mere Sahib” also reveal, that it is a city where the dementia of the past is exaggerated by the miasmic corruption of the present, and where everything promises to add in more extravagant ways to life’s misery in the future. Unlike Intizar Husain, for whom migrancy and exile are the conditions which define a Muslim and so enable each believer to regard his particular migration out of a stable community into liminal spaces as a secular variation of the grand and sacred narrative about hijrat, Manto is far too horrified by the actuality of the sufferings of the migrants themselves, be they Hindus, Muslims or Sikhs, to see in their journeys into exile anything more than an endless repetition of the days of solitude, exhaustion and waste that they have already endured. If, as Salman Rushdie says, “exile is a soulless country,” Manto knows from his own personal experiences that the cartographers of that sad place are cynics and bigots, fools and brutes, merciless killers and rapists, and that its boundaries are drawn by smoke, massacres, ash, rubble and the shattered skulls of children. All he can now do, as a migrant, an exile and a refugee in Lahore in 1951, is ‘To meditate amongst decay, and stand / A ruin amidst ruins.”

5

I should, perhaps, notice here the first words of the narrator with which the story opens : “Yeh 1919 ke baat hai Bhaijan …” (In 1919, it so happened bhaijan …).Of course, every traditional afsana or dastan begins in a similar manner. On the one hand, therefore, the narrator seems to be following the conventional formula for hooking a listener by beginning abruptly and arbitrarily so as to arouse his curiosity. What is significant, however, in the political context of the narrative, is not the acknowledgement of the traditional forms of storytelling, but the fact that the narrator begins to speak, as the train moves across blank spaces, at a particular moment of our history when our assumptions about our sense of our selves had been shattered and the presence of other human beings had become suspect and dangerous

There is no cause for the narrator to speak; no one has asked him a question and no one has invited him to give an answer or an explanation. Indeed, as we know from the other stories about the partition, it would have been safer for him to remain silent.3 Yet, he does begin to speak, hesitantly and cautiously at first, then in broken and disconnected sentences as he begins to feel safe. He gives bits and pieces of information about himself and makes fragmentary historical references. His sentences still trail away into silence and all that remains between each sentence fragment is the relentless fury of the iron wheels of the train on iron rails. He picks up his sentences again as if trying to overcome his own internal doubts, apprehensions and fears. It is obvious that it is an effort for him to fill the silence between the people in the compartment with his words and his story. But slowly his voice overcomes the empty space, the mistrust and the dread that separate him from his fellow passengers.

His opening words are the first tentative moves to restore the realm of human speech which had till recently become the site of screams and rage, of cries of supplication and pain, and of hysterical slogans filled with hate and curses (Manto had recorded the ruin of language a few years earlier in the strange fragments about the partition published under the title “Siyah Hashye”). As the narrator emerges into language and begins to discover the elementary structures of stories, he acquires a sense of himself and the listeners as human presences who are similar in kind. Language which had earlier transformed people into phantoms, once again begins to fulfil, however tentatively and momentarily, its primary function of establishing a human community. Yet, since Manto’s text tells a story of doom, at the end language crumbles back into silence and all that remains once again is the hallucinatory clatter of iron wheels on iron rails.

Further, the narrator addresses the listener, without first asking him about his religion and national identity or revealing his own, as bhaijan (literally, brother ). He does so, not only at the beginning, but with a certain insistence, throughout the story. The narrator’s use of the word bhaijan is deliberate, since in another context he uses the more familiar and colloquial word yaar (friend) to address another person in the story. Of course, the narrator is making use of the strategy which storytellers often employ to intercalate the listener into the narrative. Given, however, the fact that 1947 also represents the culmination of a long sequence of efforts to dismember a cohesive society and the sense of kinship between people of different religions, the narrator’s attempt to establish brotherhood with the listener should be read as a gesture of in-gathering and of community making. Since the listener quietly accepts the narrator’s call to brotherhood as a proper rite of address, the word bhaijan seeks to re-establish the grace of companionship (Hannah Arendt’s phrase) destroyed by the partition. At the end of the tale, however, this act of communion turns out to be misleading and false. The listener not only suspects the veracity of the narrator’s tale, but also fails to find in it anything which would console him for all the dislocation he has suffered or offer him hope for a different future. Unsure about the meaning of the story he has heard, all that remains for him is derision and bewilderment.

Contrary to the deliberate manner in which the geo-political space is left unmapped, the chronological sequence in the story is carefully crafted. While the story itself is narrated in 1951, it has two temporal locations — a few days in 1919 and 1947. Given the fact that the story is really a meditation on the partition and the reasons for the violence which accompanied it, Manto’s main concern is with showing that, though the massacres of 1919 and of 1947 occurred in radically different political circumstances and had different victims and killers, their ethical causes and consequences were similar — as they always are in every condition in which people use force to achieve the ends they desire. The use of mindless power, both in 1919 and 1947, converted living things into corpses as ruthlessly as it transformed those who employed it into grotesques ( I am using here Simone Weil’s formulation). In Manto’s understanding, 1919 haunts 1947 as its malignant shadow.

Unlike Manto, however, the narrator of the tale is blind to the relationship between the incidents of 1919 which preoccupy his fascinated attention and the violence of the partition. The listener, too, is spellbound by the narrator’s story and his own dreams of violent revenge and is, therefore, unable to see the bloody tracks that lead from the stupidity of mob violence in the streets of Amritsar in 1919 to the massacres of 1947. Both the narrator and the listener are so deeply entrapped in their own dark fantasies of suffering and retaliatory justice that they neither offer an explanation for the horrors they have witnessed nor find a vision of a more hopeful future. The scepticism of the listener, however, which calls to question many of the interpretations of the narrator’s tale, enables us to break the hypnotic control of the storyteller and his tale, and thereby makes it possible for us to pass a reflective judgement both on the fictional and the historical events described.4

‘It Happened In 1919’ (1919 Ke Ek Baat): Manto

6

IN order to reveal that the ethical presuppositions regarding violence which govern the events of 1919 and 1947 are the same, Manto employs a complex narrative strategy. He tells two stories simultaneously which demand to be read against each other — the enigmatic story told by the narrator and the nationalist story. Both begin with the Rowlatt satyagraha and Jallianwalla Bagh and end with freedom and the holocaust of the partition. The first is, of course, the fictional incident which the narrator describes to the listener. It demands that we pay attention to the sequence of events and the chronological order in which they occur because, like the listener, we have no knowledge of them prior to their being narrated. The events, which the narrator is so passionately concerned with, happen in Amritsar over four days — from the 9th to the 12th of April, 1919. The dates are important because they show that Manto’s primary interest is not with the reprehensible genocide by General Dyer at Jallianwalla Bagh on 13th April 1919, but with the protesters against the Rowlatt Act and their actions a few days before April 13th.

The second story, which is familiar both to the narrator and the listener, though each of them has his own way of understanding it, is inscribed within the narrator’s story. The narrator assumes that, since the listener’s experiences in the past are similar to his own, he also shares with him an elementary knowledge of the facts that make up the history of the nationalist movement from 1919 to 1947. He, therefore, tells the second story with the help of bits and pieces of information marking only important dates and names. These fragments of historical data are scattered at random throughout his own narration of the fictional tale. The problem for the listener, however, is that since the nationalist story is inextricably woven into the fictional tale, the reliability of the narrator’s version of the events is suspect. Manto, I think, wants the listener, and by extension the reader, to continuously check each of the references the narrator makes against known and verifiable facts, in the same way as he wants the listener to resist the temptation of accepting the fictional tale by the narrator as being truthful. It is by following the intricate manner in which the two stories are woven into each other that Manto’s intentions become clear. The careful way in which important dates are noted suggests that at the heart of Manto’s text is neither euphoria over the freedom of India nor anger over the brutality of Jallianwalla Bagh, but the barbarity of the partition in 1947 and the stupidity of violent street politics in 1919.

The first fragmentary sentence by the narrator (“It happened in 1919…”) is intentionally ambiguous. By placing the actual year 1919 and all that we (along with the listener) are presumed to know about it within a fictional frame, the narrator not only brings to our attention both the historical narrative and the invented story, but also makes us wonder about the epistemological relation between the two. The narrator’s strategy is clever and tantalising. We don’t know if we are being invited to suspend disbelief and enter a fictional realm which uses historical references primarily to achieve the effect of reality, or if we are being asked to think about the manner in which the events of 1919 are a part of the structure of the fictional narrative and constitute the meaning of the text.

Immediately after the curious opening statement whose intention is not clearly graspable, the narrator drops the fictive narrative. Unselfconsciously, he slips into a long and rambling account of the nationalist movement from March-April 1919 to 1947, cobbled out of bits and pieces of factual information, memories of actual events witnessed and personal opinions regarding their importance in the last few decades of the colonial period. Our initial response to all that he has to say in quick succession about Gandhi, Dr. Satyapal, Dr. Kitchlew, Sir Michael O’Dwyer, General Dyer, the Rowlatt Acts, or the great communal killings of 1947, is that he is only going over a history that we already know — that he is merely offering, like a dull story-teller on a long train journey, a meandering entry into the fictional world that he actually wants to reveal to us. We give — along with the listener — our lazy consent to the truthfulness of his account because, at first glance, it doesn’t seem to be different from the standard inventory of names and places which mark the years between 1919 and 1947 in all the familiar romances about our nationalist history in approved text-books.

It is not surprising that the first factual detail the narrator gives us is about the arrogant stupidity of Sir Michael O’Dwyer and his decision to arrest Gandhi under the Defence of India Act. He reiterates the popular belief that O’Dwyer’s act led to the massacres at Jallianwalla Bagh and to the eventual downfall of the British empire. In doing so the narrator makes O’Dwyer into the familiar villain of any nationalist romance. Since a nationalist romance is self-justificatory, and like the mythical figure of ouroboros, it “reconstitutes itself by swallowing its own tail” (Jerome Bruner, p. 19), we don’t pay much critical attention to the perfunctory reference to O’Dwyer and the exemplary interpretation of the entire incident by the narrator. We accept the narrator’s version as a part of a teleologically driven history, in which the inevitable victory at the end condemns the British as the enemies of freedom and offers consolation to those who had endured pain in order to obtain it. As in any nationalist fable, we are neither tempted to pay sufficient attention to the facts which are being offered, nor to consider the manner in which they are being interpreted, nor to judge the end to which they are being presented. We are lulled by the fact that the ritual invocation of the perfidy of O’Dwyer has been uttered, and the suffering of those who had struggled against him and his kind has been vindicated.

The moment, however, we remember that the story is being told in 1951 by a narrator who sees himself as an aimless and bitter wanderer after the partition, the references to 1919, O’Dwyer and others cease to be a part of a triumphant nationalist fable about reprehensible colonialists and innocent Indians. Instead of being intelligible and followable as a simple tale of victory of good over evil, it becomes entangled in a complex network of political ideas, moral problems and actual historical actions which demand “hermeneutic alertness” (Jerome Bruner’s phrase, p. 10). We are forced to look for answers to questions about the colonial period and the freedom movement which are comprehensible both within the actual historical context as well as the fictional narrative. We wonder, for example, who the narrator is? What is his national or religious identity? Whose national narrative is he concerned with when he talks about the end of the British empire and freedom? In what historical context are we being required to interpret the events of 1919? What do the narrator, the listener and Manto think about the right of a people to resist laws framed by a foreign power? What means do they think are ethically permissible to resist such laws? Who were, according to them, responsible for the great religious killings of the partition?

Thus, the chronology of the fictional narrative dislocates all that O’Dwyer and 1919 signify in the history of colonial India. Read in this manner, the opening fragment, instead of being a part of the banal repetition of the nationalist’s history which is already known and exists before Manto’s story, becomes a part of the new scandalous history of the independence movement and the partition which Manto really wants to tell. Manto’s subversive narrative doesn’t end with freedom in 1947, but crumbles into fear and silence. It shows that for him there is no ethical difference between the degenerate logic of the colonial administration, the blind fury of the mobs of 1919 and the murderous fanatics of 1947 — they are all a part of the same awful history of massacres.

Wedged in between the two fragmentary sentences about the “agitation” (Manto uses the English word) in Punjab against the Rowlatt Acts and the ban on Gandhi’s entry into the state, is a reference to Amritsar. The narrator, suddenly and without any demand for clarification by the listener, interrupts his opening sentence to specify that his concern is not with what happened in Punjab as a whole but only with events in Amritsar. The narrative placement of Amritsar in the fissure between two broken sentences which together claim that the decline of the British empire began in April 1919 is worth noticing. In the fictional narrative, if April 1919 is identified as the chronological origin of the challenge to colonialism, Amritsar is the place in the political map of India where the legitimacy of a foreign law is radically questioned for the first time. Both the narrator and the listener accept this interpretation in an unproblematic way. In doing so, they give their unquestioning acquiescence to the version of the nationalist romance in which Amritsar is only recalled as a place where first Sir Michael O’Dwyer misread the mood of the crowd which had taken out a procession on Ramnaumi day on April 9th, and then General Dyer shot down unarmed citizens who had gathered peacefully in an open field to celebrate Baisakhi on April 13. For them, Amritsar is simultaneously a place where Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs had agitated together against a foreign power and where the British had added another “bloody page” to their dark history of colonialism. The moment, however, we recall Manto’s narrative strategy, this simple structuring of the conflict of 1919 turns out to be naive and seriously flawed. Manto makes it impossible for us to forget our own complicity in the violence that swept across the Indian subcontinent between 1919 and 1951.

Thus, Manto temporarily suspends the flow of the narrative in order to focus our attention on Amritsar. The city itself is bracketed by references to two contrary tendencies that invariably marked the freedom movement — the passion of the mobs which lead to widespread violence and Gandhian satyagraha with its ethical commitment to peaceful means and self-sacrifice. Amritsar was as much a site of contestation between the two modes of political action as any other city in the country. The nationalist romance, as we know, is amnesiac towards the former and is content to repeat the truth of the latter as a ritualistic mantra without elaborating on how it actually worked in practice. Since Manto is looking for reasons why we, as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, failed to adhere to the most elementary principles of our religious thought and killed each other with the ferocity of beasts, it is not surprising that he chooses as a narrator an ordinary man, who is ambivalent towards the moral implications of the action that must be undertaken to achieve freedom. The narrator, as the rest of the story makes clear, is respectful towards Gandhi and is yet fascinated by the politics of violent revenge; he wants to believe that the protesters in Amritsar were peaceful, but longs to justify those who fought the British in the streets. It is this ambiguity of response that makes the story he has to tell worth listening to, because it gives an insight into some of the reasons for our descent into communal frenzy and murderousness in the 1940’s.

Further, Amritsar of 1919 is framed by the narrator within two distinct experiential moments in the history of the city. Both these moments lie outside the fictional narrative. The first experience that frames Amritsar and which, of course, Manto shares with the narrator, is the traumatic one of the partition and the communal carnage that followed. Amritsar of 1951 is represented as a city of death and sorrow — a city of where life is nasty, brutish and uncertain. The narrator, like Manto, sees himself as an exile from it and knows that it is impossible for him to ever return to it.

The second moment in the communal history of Amritsar, which is used by the narrator to frame the imaginary story he wants to tell, in spite of his own encounters with horror, is about life in a society of rich heterogeneity. Manto, himself, I suspect, is more antagonistic towards Amritsar before 1919. His general cynicism would never have permitted him to see any place as an example of an ideal community — though he may have permitted himself to concede to the narrator that, in contrast to what Amritsar did become, it wasn’t really such a bad place to live in for anyone.

For the narrator, however, Amritsar before 1919 is a model of a desired community. He speaks of it nostalgically as a place where Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs were aware of their different traditions and yet had an inward regard for each other as members who shared similar conditions of living, being and suffering — where they felt no sense of estrangement from each other and couldn’t imagine any cause for it in the future. Such an acknowledgement of Amritsar as a place of communal peace is significant since it is made in 1951 by a narrator who has been a witness to religious killings. Speaking out of his own intense sense of bewilderment, the narrator is quite deliberately constructing a communal history of the city in such a way as to call into question the basic assertions of the proponents of the two-nation theory who claimed that for historical reasons it was both impossible for the Hindus and the Muslims to find civic spaces where they could live together and to make a common political cause against the British. It is quite obvious however, that for the narrator the notion that the two communities were irreconcilably different is an illusion. That is why in his very next narrative move, he confidently asserts that none of the communities had any hesitation either in acknowledging Gandhi as a Mahatma or in accepting the leadership of Dr. Kitchlew and Dr. Satyapal without being concerned with their religious identities.

If, as the narrator insists, the enmity between the Hindus and the Muslims was neither natural nor culturally fated, then why did the partition occur? It is the search for an answer to that question which makes the reference to Gandhi’s role in the protests against the Rowlatt Acts and the priority he is accorded in the chronology of the story worth considering in detail. Perhaps the first thing one needs to comment upon is the fact that the respectful invocation of Gandhi is by a man who has suffered during the partition. In a story about the politics of debasement and hate, for the narrator Gandhi remains, even years later, a Mahatma, a figure of humanitas, a man who is recognised as an example of virtue by everyone because he understands that freedom and equality require nothing more than the capacity to be responsible towards oneself and attentive towards others.5 After the partition, the narrator refers to Gandhi in an attempt to recover out of the ruins some shards of dignity. Yet, as the story unfolds, we realise that since the story the narrator really wants to tell us is about the failure of just vengeance, the presence of Gandhi is meant to be seen as a sign of our civilisational failure which is so profound that nothing can save us.

The second noticeable thing about the Gandhian movement in the text is that its emphasis on clarity of thought, elegance of rational conduct and dignity of co-operative living, is negated by the melodrama of the fictional narrative which follows it with its celebration of mass enthusiasm, casual bravado, and dangerous voluptuousness. For the narrator and the listener, Gandhi is, in spite of their professed admiration for him, ethically and politically incomprehensible; a shadowy presence who disappears once the momentum of a story about a desperate “martyrdom,” with an aura of scandalous eroticism, picks up.

Historically, in 1919, Gandhi was so appalled by the mindless violence of the protests against the Rowlatt Acts in Lahore, Ahmedabad, Calcutta, Gujranwalla etc., that he broke down in public in Ahmedabad on the 14th of April and undertook a three day penitential fast to atone for the acts of his followers. Significantly enough, though his fast began on the 14th of April, he had no knowledge of the shootings at Jallianwalla Bagh the day before. Further, from March to May 21, 1919, he issued a series of twenty-one “Satyagraha Pamphlets” in which he repeatedly appealed to people that a satyagraha did not admit of violence. He urged Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs to desist, even under the gravest provocation, from acts of pillage, incendiarism, extortion, murder and rape. Searching for ways of enabling people to realise that they had the right to define themselves as autonomous individuals who could be free only if they made the ethical a part of their political actions, he urged them to take vows of self-suffering and humiliation, prayer and self-discipline, abhayadan (the assurance of safety to the innocent as a sacred duty) and religious tolerance. Only then, he was convinced, we could see ourselves and each other as members of a community instead of brutes in a crowd and participants in a duragraha. A satyagraha vow was a deliberate, self-critical and thoughtful act which could not be made without a profound awareness of the presence of the other and of his right to be different. It not only restored to each one the right to choose responsibly for himself, it also laid down a minimum moral programme for everyone which was achievable in daily practice.

Since Manto’s fictional story is not about nostalgically recovering the past, but about the inconsolable grief over our collective descent into Hobbesian jungles, it is not surprising that the narrator quickly forgets Gandhi. As the narrator continues with his tale, we realise that for Manto the presence of Gandhi is only a temporary stay against insanity. The narrator, oblivious of everything he had said in his historical preamble to the story, begins to gleefully describe the street politics of Amritsar before the 13th of April which he had witnessed. In his version, Amritsar becomes a city of labyrinths, rumours and desperate actions. Crowds surge through its streets looking for victims so that they can exorcise their own sense of humiliation and defeat. For the narrator, the marauding crowds, which he reads in terms of popular images borrowed from the French Revolution, are signs of the resurgence of vitality, a return of courage. He fails to understand, despite his horrified sense of the partition, that mob actions are always random, unpredictable and callous, that they have the terrifying fluidity of nightmares. Unlike the disciplined ethicality of the responses of the satyagrahis, the behaviour of mobs is invariably foolish and cruel because those who are swept away by frenzy have neither the time for thought nor the patience for justice (cf. Simone Weil, p. 34). According to Manto’s text and the available historical records, the furious excitement of the mobs in Amritsar soon after the arrest of Gandhi and the expulsion of Dr. Satyapal and Dr. Kitchlew, was archetypal. Convinced of their own righteousness and charged with a sense of grievance and shame, they roamed the city streets in search of a pharmokos, a sacrificial victim whose murder would give them a sense of power (cf. Northrop Frye, p.149). Given that the preferred victims of lynch mobs during riots are often women (Hans Magnus Enzensberger, p. 22), it is not surprising that Miss Sherwood became their most famous victim. The attack on her was used by the British to legitimise all their mythic fears of vicious Indian hordes and redeem their own retaliatory brutality a few days later at Jallianwalla Bagh. While Gandhi saw the ill-willed animosity towards Miss Sherwood as a sign of the “mental lawlessness” (The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.Vol. 15, p.230) of the weak, there were some like the narrator who regarded it as a necessary act of murder in any struggle for political redemption.6 What startles one about the narrator’s confession is not merely the fact that he has forgotten his earlier expressions of admiration for Gandhi — a moral amnesia he shares with many — but the specific context of his own tale in which he recalls Miss Sherwood and the gratuitous violence of his tone.

According to the actual historical accounts, Miss Sherwood was a doctor who had worked for fifteen years for the Zenana Missionary Society in Amritsar. On April 10th, after hearing about the riots in the city, she had gone on her bicycle to the five schools under her charge so as to send the six hundred or so Hindu and Muslim girls home. It was during her rounds that she was attacked by the mob. She was beaten mercilessly by young men who shouted slogans in favour of Gandhi and freedom (a fact not recorded by the narrator). Later, she was carried into the house of a Hindu shopkeeper, where her wounds were washed and she was protected from further attacks by people who came back to kill her (for details of the incident see Draper, pp. 65-66).

The narrator’s reference to Miss Sherwood comes, not at the point where it ought to have in the historical chronology of events, but at a moment of crisis in the fictional story when political violence, racial contempt, verbal derision and coarse eroticism become indistinguishable aspects of each other. There is a long and difficult sense of emptiness after the narrator finishes describing the story of Thaila, the protagonist, who attacks some British soldiers in the streets of Amritsar on 10th April, 1919, and is shot dead by them. For the narrator, it is a tale of unacknowledged martyrdom in the cause of freedom. For a more objective critic of the story, however, it is a predictable adolescent romance full of bravado and enthusiasm but of little political significance. In the embarrassed silence that follows the end of the story, the listener feels as if the wheels are repeating, with dull mechanical regularity, the last phases of the narrator, “Thaila is dead, Thaila is buried…Thaila is dead, Thaila is buried…” These fragmentary phrases, echoed by the clatter of wheels, seem to reduce the story of Thaila to a mundane and inconsequential incident. Ironically, the narrator fails to see that there is a disturbing gap between his own expressed admiration for Gandhi and his agony over the death of Thaila, and that there are two political possibilities indicated within his own narrative. Thaila’s spontaneous decision to kill a British soldier may be full of exultation and energy, but it can’t be read as an act which is either personally redemptive or nationally desirable. He is a drunkard, a braggart, a gambler and a bully. There is nothing in the story to indicate that he is a man concerned with national questions. He acts merely on the impulse of the moment. It is, therefore, surprising to find that Leslie Fleming, in her study of Manto, is oblivious to Manto’s ironic rage and applauds Thaila as a political activist and bemoans his fate. To do so is not only sentimental nonsense, but is also, in Gandhian terms, an abdication of ethical and political will to the whims of a hooligan (The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, No. 15, p. 234). If Thaila has political legitimacy and is a martyr, then so is Dyer; both are mirror images of each other, for the will to power of one is countered by the will to destruction of the other. Thaila doesn’t have the intelligence to ask if freedom is worth having at the cost of such murders; Dyer lacks the moral grace to consider if the Empire is worth saving. In Manto’s demonology of the nationalist movement, they are both nasty examples of what William Blake identifies as that grotesque condition when “the soul drinks murder and revenge applauds its own holiness.”

There is a further slippage between Gandhian ethicality and politics, and the narrator’s unreflecting modes of thought and action. The narrator tells the listener in grave tones that the most tragic aspect of his tale is yet to follow. Immediately afterwards, however, he forgets his rage over Thaila’s death. Instead, he begins to describe in sensuous details, the mujra Thaila’s sisters used to perform for the entertainment of their customers in Amritsar. The listener feels uncomfortable as the narrator loses himself in his recollections of the night world of a sexual epicure. The narrator, however, is incapable of noting that there is little difference between his desire to ‘colonise’ and ‘raid’ the bodies of the dancing girls for his own delight and the coercive politics of the Empire. It is beyond his capacities to acknowledge, what moral politicians from Gandhi to Simone Weil have consistently pointed out, that the voluptuary and the coloniser are the same; and that both are so intoxicated by their power to possess and defile their victims that they themselves become grotesques.

After a while, the narrator emerges from his sexual fantasia and resumes his story. He describes how, soon after Thaila’s death, some British soldiers heard about his sisters and demanded that they dance for them. He bitterly condemns those Indians who told the British soldiers about Thaila’s sisters as “toadies” who, like all collaborators, always put themselves “voluntarily at the service of vile power” (the formulation is Kundera’s, p. 125) in order to increase the pain of the defeated. It is during the description of this lurid incident that he suddenly recalls the historically factual attack on Miss Sherwood and inscribes it into his fictional narrative. It is , perhaps, worth noting here that in the larger framework of Manto’s text, attacks such as the one on Miss Sherwood were for Gandhi a violation of abhayadan, which was not only an important duty of a satyagrahi, but was also the “first requisite of religion” (The Collected Works Of Mahatma Gandhi. Vol. 15, pp. 222). The narrator, who has already forgotten Gandhi, unexpectedly bursts into rage, and in an act of compensatory retaliation calls her a chudel (a bitch). His verbal assault is, of course, a sign of the fact that he is still so deeply marked by his memories of social defilement that he hopes to recover for himself some sense of pride. The irony is that while he curses Miss Sherwood and is touched by the fate of Thaila’s sisters, he fails to see that the entrapment of the dancing girls is not only similar to the predatory attack on the English woman but is also one of its causes. What is shocking, however, is that he forgets that between 1947 and 1951 enraged mobs of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs had applauded public acts of sexual debauchery and had justified them as fair compensation for their political and religious humiliation at the hands of each other. To take only one example out of many, Kamalabehn Patel recalls that “200 women were made to dance naked for the whole night” in the central hall of the Durbar Sahib in the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and that many people had “enjoyed the unholy show.”7

While the narrator effaces an obscene present, his memories are still haunted by a past in which nostalgia and pain, loss and desire are strangely mingled. When he resumes his story, at first he offers a fairly conventional comment about the inability of people to believe that even dancing girls can have feelings. Then, he adds, with seeming innocuousness and without any challenge by the listener, that “this country has no sense of self-respect.” The statement becomes treacherous, however, the moment we recall that it is being made in 1951 by a narrator who doesn’t know where he belongs. In the absence of the name of the nation, we wonder if the country he refers to is India or Pakistan? We also wonder if he is so profoundly lost in the shadowlands of memories that he unselfconsciously assumes that, as in the past, the two new countries shall continue to share the same civilisational space and a common history — and hence, of course, be equally involved in the present shame? The ambiguity of the narrator and the listener towards the formation of the two nations is bewildering. Indeed considering that one reason for the violence of those days was to ensure that the demarcation between the two countries was deeply and ineradicably engraved in the minds of the people, the forgetfulness of the narrator and the listener adds to the phantasmagoria of the story and of the times.

The narrator’s tale has two different, but equally scandalous endings. In the first version, Thaila’s sisters rip off their clothes, dance naked before the British soldiers and then give a sexually graphic speech, charged with nationalist rhetoric, about their brother’s sacrifice for his country’s freedom. Mixing politics, eroticism and death, they ecstatically invite the soldiers to “pierce” their “beautiful perfumed bodies” with the “hot irons” of their lust. They also, however, request the soldiers to let them “spit on their faces.” After a pause, the narrator, with tears in his eyes, adds that the soldiers responded to the passionate defiance of the sisters by shooting them dead. In the second version, which the narrator admits is more truthful when he is questioned by the listener, the sisters perform a mujra for the entertainment of the soldiers. The ending of the first version satisfies the narrator’s offended pride, while the ending of the second corresponds to his sense that the times are utterly depraved. What he doesn’t realise is that ethically there is no difference between melodramas of retaliatory violence or of base surrender; that both are without meaning, without purpose and without end; that as Blake says, “The beast and the whore rule without controls …”

For Manto, the writer, contemplating the partition from Lahore in 1951, there is a physical, moral and political logic which links the profane desires of the narrator, the massacre at Jallianwalla Bagh, the prurient delights of the British soldiers and the fatal fraternities of mobs from 1919 to 1947. Together, they form a random anthology of incidents in an awful and inexorable tragedy of a degenerate society. All he can do, as he records these tales, is to lament — and lamentation, as we know from religious and psychological sources, is that state of inconsolable sorrow in which one feels that nothing more purposeful will ever offer itself again.

References 1. The Congress report on Jallianwalla Bagh concludes that O’Dwyer “invariably appealed to passion and ignorance rather than to reason” (p. 7). It adds that “he invited violence from the people so that he could crush them” (p.23). The report also records a meeting between Raizada Bhagat Ram and O’Dwyer which gives some indication of the latter’s frame of mind during the Rowlatt satyagraha. Bhagat Ram told O’Dwyer that the meetings had been peaceful and added, “To my mind it was due to the soul force of Mr. Gandhi.” Hearing that, O’Dwyer raised his fist and said, “Raizada Sahib, remember, there is another force greater than Gandhi’s Soul-force” (p. 44). Punjab Disturbances. Vol.1. The official British report also condemned Dyer’s acts as “inhuman and un-British” (p. xxi), but added that “he acted honestly in the belief that what he was doing was right...(p. xxii).” The Indian members of the British Commission refused to endorse these views. Punjab Disturbances 1919-20. Vol. 2. 2. On 18 April 1919, Gandhi admitted that his call for civil disobedience against the Rowlatt Acts was a “Himalayan blunder.” Cf. Judith Brown, Gandhi : A Prisoner of Hope. 3.In the stories about the partition by Manto and others (as in numerous accounts of the Jewish holocaust -- and incidentally, in spy-fiction), speech can often lead to betrayal and death. This is, of course, contrary to the assumption of saner societies in which speech enables the world to come into being and ensures the on-goingness of life. 4.It is perhaps worth recording that, while there are countless stories in which hypnotic or mesmeric control leads to brutal death (e.g. Poe or Dickens etc.), tales of enchantment can also result in redemptive release from irrational fears or social rage (e.g. The Arabian Nights at one end and Freud at the other). 5. The Hunter Commission report also records that in Punjab in 1919 Gandhi was respected as a rishi by the Hindus and as a wali by the Muslims. Punjab Disturbances. Vol 2, p. 36. 6. General Dyer, for instance, told the Hunter Commission, “I felt women had been beaten. We look upon women as sacred...” He added, that the street where Miss Sherwood had been beaten “ought to be looked upon as sacred...” (p. 61). Punjab Disturbances. Vol. 2. 7. Kamalabehn Patel, “Oranges and Apples,” India Partitioned. Vol. 2. Ed. Mushirul Hasan. Works Cited Arendt, Hannah. Between Past and Present. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977. Bhalla, Alok. Stories About the Partition of India. New Delhi: Harper Collins, 1995. Braudel, Fernand. On History. Trans. Sarah Matthews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980. Brown, Judith. Gandhi: A Prisoner of Hope. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1989. Draper, Alfred. Amritsar: The Massacre that Ended the Raj. London: Macmillan, 1981. Enzensberger, Hans Magnus. Civil War. Trans. Piers Spence and Martin Chalmers. London: Granta Books, 1994. Flemming, Leslie. Another Lonely Voice: The Life and Works of Saadat Hasan Manto. Lahore: Vanguard, 1985. Freud, Sigmund. “ Mourning and Melancholia,” Collected Papers. Vol. 4. Tans. Joan Riviere. London: Hogarth Press, 1925. Frye, Northrop. An Anatomy of Criticism. New York: Atheneum, 1969. Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Vol. !5. Ahmedabad: Navjeevan Press, 1965. Gould, Stephen Jay. Bully for the Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History. New York: Norton, 1991. Hasan, Mushirul. India Partitioned: The Other Face of Freedom. Two volumes. New Delhi: Roli Books, 1995. Husain, Intizar. Leaves and Other Stories. Trans. Alok Bhalla and Vishwamitter Adil. New Delhi: Harper Collins, 1993. Kermode, Frank. The Genesis of Secrecy: .On the Interpretation of Narrative. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979. Kundera, Milan. The Art of the Novel. Trans. Linda Asher. New York: Harper and Row, 1986. O’Dwyer, Michael. India As I Knew It. Delhi: Mittal, 1988. Punjab Disturbances: 1919-1920. Two volumes. 1920; rpt. New Delhi: Deep Publications, 1976. Ricoeur, Paul. Time and Narrative. Vol. 1. Trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1984. Weil, Simone. Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks. London: Ark Paperbacks, 1987.

Notes --This essay was published in Life and Times of Saadat Hasan Manto, edited by Alok Bhalla (Shimla: Institute of Advanced Study, 1997). The volume is now out of print. --The Beacon wishes to thank Alok Bhalla for making available this work. --The image of George Grosz painting accessed from: https://www.heckscher.org/endless-summer-well-how-about-endless-art/

Alok Bhalla is at present, a visiting professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia. He is the author of Stories About the Partition of India (3 Vols.). He has also translated Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug, Intizar Husain’s A Chronicle of the Peacocks (both from OUP) and Ram Kumar’s The Sea and Other Stories into English.

Alok Bhalla in The Beacon A Prayer For My Daughters: Alok Bhalla WHEN KABIR SAW, HE WEPT… Ahimsa in the City of the Mind: Language, Identity-Politics and Partitions Stand by Me: Song of a Farmer The Self As Stranger I Am A Hindu

Leave a Reply