Zahara and the Lost Books of Light Joyce Yarrow. Adelaide Books. December 2020. 432 pages

Bhaswati Ghosh

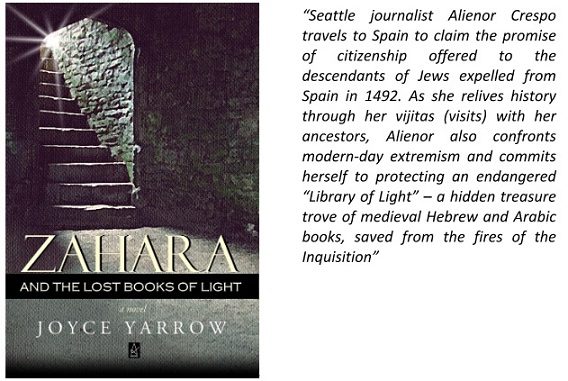

Zahara and the Lost Books of Light by Joyce Yarrow is that rare book that is at once topical and timeless. Yarrow teleports her readers across centuries to help them relive La Convivencia — a unique period in Spanish history when the three Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam coexisted in relative peace. Alienor Crespo, the present-day narrator of the novel is the descendant of a Jewish family, which, along with other members of its faith, was expelled from Spain in the 15th century. To tell this story set across time and space, Yarrow seamlessly traverses between history, fantasy, journalism and the thriller-genre. Through Crespo’s gift of vijitas, a Ladino word meaning visits, the reader is able to smoothly slide back and forth in time, while confronting some hard truths about ultra-right politics and the astonishing power of the written word.

I came to know Joyce Yarrow through Facebook several years ago. She was already a published author with a few books to her credit, while I was still what the publishing world has come to label as the “aspiring writer”, one without a significant publishing history. In the years to follow, we grew to be close writing pals, and I benefited greatly from Joyce’s feedback on the manuscript of my debut novel, Victory Colony, 1950, published by Yoda Press in August 2020.

I had enjoyed reading Rivers Run Back, a novel set in India and Canada that Joyce co-authored with Arindam Roy in 2015. When Joyce was drafting Zahara and the Lost Books of Light, I was privileged enough to read the initial chapters, which had me mesmerized. When the book was finally published in December 2020 and I read it in full, I wasn’t disappointed in the least. Joyce’s crisp prose – illuminating and fast-paced at once – combined with the subject and setting of her novel, took me on a time-travel adventure like none other. In a year of home-bound isolation, one couldn’t have asked for a more vicariously pleasurable reading experience. The element of mystery is crucial in Joyce Yarrow’s writing, and this is a strength that makes her stories gripping page-turners. Joyce is a Pushcart nominee and teaches workshops on “The Place of Place in Mystery Writing.”

As I read Zahara, I was intrigued not only by the book’s meticulously constructed plot and narration, but also by the research and rigour that went into it. I decided to ask Joyce how she did it all. Here’s a transcript of our email conversation.

Bhaswati Ghosh: When did you first think of writing Zahara and the Lost Books of Light? How did you come up with the title?

Joyce Yarrow: The seed for Zahara and the Lost Books of Light was planted many years before the actual writing began. On September 11th, 2001 my dear friend and musical partner Samia Panni called me to express her horror that a crime of such magnitude had been perpetrated and to share her fear that innocent Muslims living in America—the vast majority of whom were peace-loving citizens like herself —would be blamed for the destruction of the World Trade Center. Hailing from Bangladesh, Samia had co-founded the world Music singing group Abrace with me. And on that day we rededicated ourselves and the group to promoting inter-cultural understanding through music.

One of the songs that we added to our repertoire was Cuando el Rey Nimrod. Composed in Ladino (the language of Spain’s exiled Jews) this song mixes Arabic rhythms with Sephardic lyrics that celebrate the birth of Abraham. On stage, we always introduced this classic Sephardic song with a fervent wish that someday Christians, Jews and Muslims would acknowledge their common patriarch and decide to live in peace.

The song also sparked my interest in the period of medieval Spanish history known as La Convivencia —when artists, poets, scientists and philosophers from all three religions collaborated and interacted with great enthusiasm and creativity. And then, one day—seemingly out of the blue—I asked myself: if La Convivencia had managed to survive into modern times, what form would it have taken? This ‘what if’ question generated the heart of the story I began to write.

I chose Zahara as the title because it means ‘light’ in both Hebrew and Arabic and I hoped it would guide me if I lost my way in what I knew would be a difficult but hopefully rewarding endeavor. My agent added “And the Lost Books of Light” to the title after I had finished writing the book.

BG: Why did you feel compelled to write about this subject?

JY: Growing up in an area of the East Bronx that was basically a war zone, with ethnically-based street gangs constantly at each other’s throats, was my earliest lesson in the need for more tolerance and understanding in our world. I took refuge in the library, which at one point was the only undamaged building remaining in our neighborhood. And so it was that books became my passport to other more friendly climes and I came to value them with reverence. Perhaps this is why the idea came to me to write a story in which some of the codices burned by the Spanish Inquisition were saved and hidden away in the mountains outside Granada.

BG: You’ve employed an element of fantasy in this story that travels through centuries. Though fantastical, I was struck by how real the vijitas felt. How did you a) come up with the idea of these inner journeys and b) make them appear credible enough for the reader?

JY: This is a question for which I do not have a facile answer but I will try. To begin with, I knew that the story I was writing would require some time-shifts in the telling, as well as some strong historical background to shed light on the importance of the ancient texts that Alienor Crespo helps to rescue. As I developed Alienor’s character, her devotion to truth-telling through journalism struck me as one of her strongest attributes. It was one step from there to bestowing on her a gift: vijitas (the Ladino word for ‘visits”) during which she is able to see through the eyes of her female ancestors. My hope was that as she experienced history directly, so would the reader.

![]()

However, as is the case with all gifts, there is frequently a down-side. In Alienor’s case, her childhood experiences of seeing the Holocaust first-hand and visions of the persecution of the Jews in 15th-century Spain, terrified her. Choosing journalism as a profession became her way of balancing the two realities in which she lived. As Alienor describes it when talking with her newfound Spanish cousin, Celia: “I consider myself a logical person mistakenly connected to the inexplicable.” As it turned out, her conflict about the vijitas resulted in them becoming more credible to the reader.

As she confronts the challenges that await her in Spain, Alienor discovers that her vijitas can be very useful and at one point they begin to intersect with and inform her experience of the present. She fully embraces her gift and this is a turning point that leads to the dramatic resolution of the story.

BG: What was it like to research for this book? Did you make multiple trips to the locations the book is set in? Tell us a bit about your process of gathering information.

JY: I began my research with multiple trips to public and college libraries over a period of six months – to the extent that my husband asked me when I was going to stop checking out books and start writing. “Not anytime soon,” I answered, as I continued to devour volumes about the literary achievements of Jews and Muslims in pre-medieval Spain, the brutalities of the Inquisition, the expulsion followed by the Sephardic diaspora, Franco’s dictatorship, and modern day religious and political extremism. I would probably still be reading, if I hadn’t scheduled a trip to Andalusia, forcing myself to write a few chapters so I could follow in Alienor Crespo’s fictional footsteps.

Although I stopped in Málaga and Granada, the most evocative place by far was La Alpujarra, where much of the action in Zahara and the Lost Books of Light takes place. La Alpujarra is the home of the pueblos blancos – white towns – where flat rooftops typical of Morisco houses still prevail, the steep hillsides providing a precarious but somehow permanent setting that makes them feel somewhat frozen in time.

My second trip to Spain took me to Ceuta – a Spanish city-state next to Morocco—where I interviewed residents who have created a modern Convivencia, co-sponsoring festivals that are shared by Hindus, Muslims, Jews and Christians. More about that in the sequel to Zahara that I’m currently writing.

Back home in Seattle, as I dug into the writing process I was very fortunate to receive help and encouragement from several scholars of Spanish history who were generous with their time and expertise. One authority on Muslim libraries was kind enough to suggest the titles of books that might have been burned by the Inquisition in 1498.

BG: Your descriptions of the Spanish countryside and its historical past are delightfully engrossing. What were you mindful of when writing these scenes so as to make them come alive to the reader?

JY: Thank you! At the risk of sounding a bit mystical myself, I do give Alienor Crespo credit for letting me see some of Spain’s history in tangible form through her ancestor’s eyes. This was not difficult in a country where Moorish architecture is still prevalent and century’s old irrigation systems remain largely intact. I took many photos during my research trips and relied on them to bring me back to particular times and places after I returned home.

One of Alienor’s ancestors is Jariya al-Qasam, a Morisca ‘bandit’ whose real mission is to rescue children who have been kidnapped by the soldiers of the Reconquista with the intention of selling them into slavery. As I walked the hills of La Alpujarra I visualized Jariya so clearly, disguised as a Dominican Friar to put fear into the hearts of the soldiers she hoodwinked. I found the mulberry trees were still there, although not as numerous as they were when the Moriscos produced silken clothing that was famous the world over. All of this found its way into the book quite naturally.

BG: In the book, you also shine a light on right-wing extremism, which, unfortunately, has seen a resurgence in many parts around the world. Why was this an important theme to you?

JY: One writing technique that authors of suspense embrace is that your protagonist can only be as strong as his or her antagonist. When I researched who might be opposed to bringing back the spirit of Convivencia, I was dismayed to find that denial of Spain’s cultural legacy and debt to Islamic and Jewish culture is still rampant. The villains I created were based on real people and events that involve a real right-wing-extremist political party that has gained ground in the Spanish government.

During the three years over which I wrote the book, this nationalistic, xenophobic outlook was on the rise throughout the world, spreading much like the Covid-19 virus we are plagued by today. In a way, writing Zahara was therapeutic for me, in that I created an opportunity to present an alternative to hate, even if in fictitious form.

BG: Will there be a sequel to Zahara? What are you working on next?

JY: There is a sequel to Zahara in progress, but I am not quite ready to reveal the title.

*******

Bhaswati Ghosh lives in Ontario, Canada and writes and translates fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Her writing has appeared in several print and online journals. Her first book of fiction is Victory Colony, 1950. Visit her at bhaswatighosh.com More by Bhaswati Ghosh in The Beacon “Victory Colony, 1950”: An Excerpt PLAYING WITH ‘FIRE OF CREATION’: RAMKINKER BAIJ THE WHORE AS METAPHOR FOR A CITY

Bhaswati adopting a ‘chat’ approach with her friend Joyce as a means to introducing ‘Zahara and the Lost Books of Light’is an engaging way to get the reader to pick up the book, post haste.

Joyce’s answers to Bhaswati’s crafted probes, promises a “thriller-genre” of a narrative ride, while bridging an old secular history of an ‘expelled’ community with the current reality of divisive extremism.

The Q&A perfectly sets the stage, enticing the reader to get into the well researched time travel world the author offers to share, through the eyes of her protagonist Alienor Crespo.

Thank you both…this is exciting fare ahead!

Thank you so much for your comments! So glad you enjoyed the read.

Thank you so much for your keen reading and thoughtful observations, Pankaj Dutt!