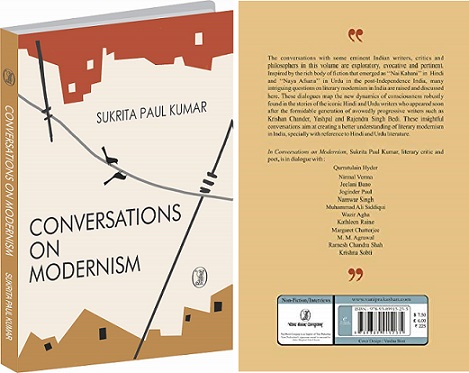

Conversations on Modernism. Sukrita Paul Kumar. Vani Prakashan. Imprint of Vani Book Company Daryaganj New Delhi. August 2020. Pp 190

Prelude

Sukrita Paul Kumar’s dialogic interactions with leading Urdu and Hindi writers from South Asia, writers who offer a critical and lively glimpse into their world of creativity and its preoccupations, indeed into the aesthetics of their vocation form an invaluable addition to the rather meagre library of literary engagements that shine the light on more than just the art of fiction. The Beacon wishes to thank Sukrita Paul Kumar, the author and Aditi Maheshwari of Vani Prakashan , publishers of the book, for permission to reproduce the Introduction in full and extracts fropm Kumar’s copnversations with Qurratulain Hyder and Nirmal verma. .

Sukrita Paul Kumar

Introduction

Understanding ‘modern’ Hindi and Urdu fiction means understanding the interface of the writer of ‘nayi kahani’ or “naya afsana” (new story) with the reality of the 60’s and 70’s of the twentieth century India. The post-Independence/ post-Partition life experience compelled fresh creative articulation in the changed socio-political environs. Writers projected their capability of at once experiencing reality as well as stepping outside it to understand, assess, and locate new forms to express and define the new reality. Twentieth century literature from all over the world in fact presented a whole range of new forms and styles through which the writer chose to delineate and capture the changing realities. The traditional, apparently straight-jacketed forms seemed inadequate to contain the broad and complex spectrum of human experience: the new vistas opened through an intensely philosophic and psychological probing into human existence and its place in the universe. Modernism, a rather elusive concept, emerged as a blanket term, a convenient label to describe the new dynamics of human consciousness.

Mid-twentieth century Hindi and Urdu fiction seems to evince some of the same preoccupations, strategies, and stylistic choices as did literature in early-twentieth century Europe. There seemed to be a distinct and deliberate divergence from ‘tradition’ accompanied by a social disruption, an awareness of emptiness, a general loss of individual identity, and an experience of loneliness and estrangement. A scan of the post-Independence Urdu and Hindi short story demonstrates a heightened questioning of values, disillusionment, and what may be termed as ‘modern temper’ tinged with some cynicism. It is precisely this body of literary work that has inspired these dialogues in the present volume. As the reader approaches the individual artist’s imagination through her or his fiction, it becomes increasingly necessary to comprehend the sensibility which actually produced that work.

The following dialogues with eminent writers of modern Hindi and Urdu short fiction, critics and philosophers, were undertaken to place and interpret modern Urdu and Hindi fiction within a larger, global, social and artistic framework. The intention is to strive to define the artistic climate of Indian modernism as backdrop to the critical and philosophical approaches to these literatures. In these conversations there is an attempt to make the writers step out of their work and consider themselves the product of a specific culture. At times, they return to their original state of creative adventures while recalling the creative process. Whereas celebrated writers in the west have developed defences and acquire public personae that allow for little spontaneous interaction, the Indian writer – fortunately is far more accessible. Unguarded and unpretentious dialogue with them is more forthcoming, making the exercise meaningful, unpredictable as well as enjoyable. Indeed, the dynamism of the dialogue depends on the undercurrent of understanding and the mutual responsiveness of those in conversation. Just as writers dispensed with the private lines beyond which they would not usually articulate their process of writing, the interviewer acted as appreciative audience, impartial witness, and at times even as critical authority as the need arose, sometimes remaining in the background as a quiet presence merely ensuring the continuity of communication. The questioning needed to be both incisive and receptive.

Since the term ‘modern’ designates a distinctive kind of imagination expressed through specific themes and literary forms, I have sought in every interview to newly understand the concept with each distinctive mind. The breadth of intention and style perceived in modern Hindi and Urdu writing awaits a comprehensive analysis for a definition of modernity and modernism that may be arrived at. The modern, which is at once immediate and obscure, intimate and elusive, is not merely a chronological description. Though intellectual and philosophical explorations of modernism have been attempted, an objective examination of literary modernism seems to have been evaded for a long time. Particularly in the Indian context, even though a shift in sensibility is easily discernible, adequate critical analysis of the phenomenon is missing. Does literary Hindi and Urdu modernism project indigenous, authentically Indian concerns or does it dominantly reflect Euro-centric modernisms? Since modernism implies a kind of disinheritance, does the vacuum get filled with alien concepts and values? How much of the experiential quality of modern Indian literature smacks of western influence? Can we evolve a definition of modernism which is strictly and convincingly descriptive of the Indian reality? These are some of the intriguing questions raised in the ensuing discussions. The purpose is exploratory. There is no attempt to argue a specific theory of modernism. However, some insights that emerge in these dialogues may help to design some theoretical premises

The vociferous voice of the eminent Urdu writer Qurratulain Hyder clearly blames critics for not demonstrating genuine concern for literary works, and as the Hindi writer Nirmal Verma too points out, there is dearth of critical feedback or intellectual stimulation for the modern Indian writer. Jeelani Bano, who also writes in Urdu, takes a similar stance against the critical climate characterized by complacence; she particularly criticizes the “awards culture” and the consequent politicking in Urdu literary circles. What seems to emerge then is that the modern Indian writer tends to be particularly self-conscious about being in an insular world. In these conversations then, ranging from momentary crystallization of responses to ideas and beliefs, statements of these writers are testimony to what kind of minds are at work, at once creating and responding to reality and imaginative situations.

Nirmal Verma recommends that specific distinctions be made by the critic between, say, the loneliness in a tradition-ridden Indian society where families are beginning to break, and the loneliness in a so called ‘liberated’ individuated western society. Naive comparisons do not help to evolve the understanding of a distinctive Indian modernism/s. A matter of great concern, notes Verma, is the lack of even a mechanical critical cognition of the past in Indian writing. “We are living,” he says, “without any mythological past.” This focuses attention on an important distinguishing feature: in the west, the literary modernism of Yeats and Eliot creates a nostalgia for the past through a dominant literary use of myth and history.

A discussion on the creative process with one of Urdu’s major writers, Joginder Paul, unravels the modern writer’s liberation from traditional constraints that a literary form may impose on the creative imagination. His sharp awareness of the limits of ‘freedom’ for the writer, and his utmost commitment to the authentic representation of a creative experience projects the modern writer’s sensitivity to the question of genuineness of artistic expression. Talking about the literary form, Kathleen Raine says, “Form, in reality proceeds from life itself, as in the form of a plant; it grows from life itself.” The creative process then, to a modern writer, denotes a discovery of the artist’s own form and style, through an essential contact with the reality of experience.

Wazir Agha, a critic and also himself an important poet in Urdu, makes a very valid point when he talks about the easy cross-fertilization of ideas between the east and the west in the modern world. An awareness of alienation then, as he says, is not the monopoly of the west or that loneliness cannot be a feature of merely of urban literature. About the same question, Mohammed Ali Siddiqui, a distinguished critic in Urdu from Pakistan, maintains that some of the modems in both India and Pakistan have been able to absorb western modernism and readjust it in accordance to the local context, while some are quite medieval and obscurantist. He criticizes what he calls glamorization of certain notions and romanticization of fetishized artefacts: say, for instance, the bullock cart. This kind of nostalgia according to him retards progress or futuristic thinking. Indeed, to propound theories of what modernism is may stifle the rather open, many-layered consciousness of the creative writer. Siddiqui would rather not create any definitions which might limit the scope and diversity of the concept of modernism.

It is in such a context that Ramesh Chandra Shah’s perceptive comment about the modern mind having discovered the value of the pagan and developed a pluralistic sensibility acquires a particular relevance. What Nietzsche and Marx did to the western psyche, he remarks, Gandhi and Sri Aurobindo did in the Indian situation, as shapers of modern Indian psyche. However, the lack of swaraj in ideas, a failure to confront and define the Indian situation and the tendency to locate solutions in alien cultures, makes literary modernism too literary in India. He quotes the names of some modern Hindi writers who appear as “modern men in search of a soul” and those who try to give evidence of ingenuity through their creative ventures.

Namwar Singh looks at ‘modernism’ as an experience of reaction, acceptance, and rejection of the transformation of sensibility. He qualifies the modernism of the late thirties in India as less of an experience and more of an intellectual exercise which seeped into Indian culture gradually and evolved into a real experience much after Independence.

It is interesting to note the differences between the two philosophers Margaret Chatterjee and M. M. Agrawal in this volume, in their answers to the questions raised. Margaret Chatterjee recognizes how cosmopolitanism is built into what might be called ‘modern’. She looks askance at those who continue to talk of tradition and put the clock back politically, socially, and in other ways in the name of Indianness. She connects this with xenophobia and calls this feature “anti-modern” and believes that modernism amongst the fanatic traditionalists is a mere veneer. M.M. Agrawal, on the other hand, traces the emergence of modern values and fresh concerns in the Indian society from the very beginning of the twentieth century. He refers to the late nineteenth century/early twentieth century Indian Renaissance as a period of Enlightenment and shows how an axiological revolution took place then, bringing about a change in the social structure of the country. Secular ideas, rational thought, and scientific outlook got injected into the national bloodstream then. Establishing a love-hate relationship between tradition and modernity, he shows how modernity draws its justification from the very past it seems to be rejecting. Since the moral authority sought to justify new ideas and fresh values, modernity gets assimilated and indigenized while relating to the Indian past.

This volume presents a valuable addition to the list of writers in conversations – that of the eminent Hindi writer Krishna Sobti. It is my good fortune that I had been in an on-going dialogue with Krishna Sobti over a number of years towards the end of her life. Even though there was no organized dialogue with her on modernism as such, I decided to include her voice in this volume, primarily because she was a formidable contemporary of the writers in this book and her ample contribution to “modern fiction” in Hindi facilitates the understanding of the modern temper in Indian literature. The autonomy she cherished for herself gets reflected in her pulsating characters, each of whom carve out their own destiny, be it Mitro of Mitro Marjani, Mehak of Dilo Danish or the mother of Ay Ladki.

These discussions with writers, critics, and philosophers demonstrate how specific interrogation may transform into a collective conversation. The interviewer has tried to retain the dynamism of the exchange of ideas alongside presenting a faithful transcription. Further, the mode of questioning and the direction of the discourse depended largely on the interviewer’s understanding of the writings of the interviewed writers. Third, since modernism and the representation of the modern stance in literature are fused into each other, the philosopher’s or the critic’s perceptions are as illuminating as those of the writers. And finally, these interviews attempt to record the voice, the thinking voice, of those interviewed. This voice is oftentimes different from that heard in their written words. The spoken word offers a dimension of expression that may not be available in writing. These conversations were held in in Urdu, Hindi or/and English to maintain the comfort level of the interviewees. The translation into English was done soon after, and each text produced was approved by the interviewee for publication.

***

QURRATULAIN HYDER: ON THE MODERN SHORT STORY AND THE CRITIC IN URDU

![]()

Padma Bhushan Qurratulain Hyder (1927-2007) was without question the grand dame of post-independence Urdu writing. She was honoured with the Jnanpith Award and the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship. She received the Sahitya Akademi Award for her short story collection Patjhar ki Awaz. Her magnum opus Aag ka Darya, an extraordinary telling of subcontinental history and an enactment on the action of time itself, was translated into fourteen languages by the National Book Trust. She herself “recreated” the novel in English forty years after its original 1959 Urdu publication. Educated in India and abroad, Hyder was associated in various important capacities with publications such as the Daily Telegraph, London, The Imprint, Bombay, and The Illustrated Weekly of India. She also served as broadcaster for the Urdu Services of the B.B.C. and as Adviser to the Chairman, Central Board of Film Censors. A Visiting Professor at Aligarh Muslim University and Professor Emeritus, Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan Chair at Jamia Millia Islamia, she also lectured extensively at the Universities of Chicago, Texas, California, and Arizona, and she served as resident for the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. Her work is compared in scope with that of Gabriel Garcia Marquez; her influence on Indian modernism has been profound, and she is much celebrated for her contribution to Urdu literature.

SUKRITA: Philosophers and literary critics have expended many words on the “loneliness” of a creative artist. I would like to begin our discussion with the peculiar sense of loneliness that you may have encountered as a woman creative writer, writing in Urdu in India. Have you been conscious of being situated at an uncommon intersection that may have caused a discomfort to you as a writer? Or has that been a position of privilege? Do you have any specific experiences related to loneliness?

QURRATULAIN HYDER: You have asked three questions; one is regarding the loneliness of the creative writer. This may sound rather pompous but let’s face it, it is very much there. It has always been there, with any artist anywhere in the world. A writer writes in isolation. The loneliness of a western writer is framed sociologically, but we are not concerned with that now. You have another point – the loneliness of a woman writer. Well, a woman writer, whether in the west or here in the east is more or less in an identical position. And then, to accentuate it further you speak of the loneliness of a woman writer of Urdu. That loads the question, and to top it all, a woman writer’s loneliness writing in Urdu in India!

Ah well, perhaps it is not really all that bad! Writing in Urdu in India makes no difference – writing in Urdu in Canada, Pakistan or anywhere else, according to me, would not change the situation. And then, a woman writing in Urdu in India or a man writing in Urdu in India would also be the same. Women have been writing in Urdu for the past hundred years. The first woman novelist wrote at more or less the same time as the first man novelist. The point – a woman writing self-consciously – and we return to a situation common to women all over the world.

SUKRITA: But what of the cultural context? George Eliot had to adopt masculine nom de plume to escape the critical bias against women’s writing in nineteenth-century England. Till about fifteen, twenty years ago the situation in India was perhaps the same? Did the evaluation of your work ever depend on your femininity, did that ever affect your self-consciousness which you had to make an effort to rid yourself of while writing? In selecting the theme of your creative venture or the adoption of a stance?

QURRATULAIN HYDER: It may surprise many to know there has never been the kind of segregation of men and women in Urdu literature you might expect from a society that practices such segregation in life. I think we must understand this peculiar phenomenon at the outset. There have been women writing fiction and there have been women writing poetry. The male chauvinistic patronization –that one encounters anywhere in the world…I think it was never so emphatic here and the woman was not affected enough to be disturbed as a writer. She didn’t have to worry. My own mother started writing at the age of thirteen or fourteen and there was no question of any criticism of the kind there would have been in the case of a woman coming out of purdah – a woman could have been writing even romantic short stories or novels.

As for me, what I am perturbed about is not this gender self- consciousness, but the fact that critics in Urdu are generally not attentive to what is happening-in fiction at all. There is clear-cut neglect of fiction by the critic in general. There has been no serious critical focus on fiction in Urdu. My own writing suffers as a result.

SUKRITA: Does that result in an exclusiveness of sorts or an isolation of the writer?

QURRATULAIN HYDER: No, I don’t feel that at all. I am not an isolationist, nor am I a celebrator of loneliness. My concern is that my work suffers from the lack of any active and lively literary give and take – you know, a literary life, as it were. There is a general indifference. I don’t mean that I need critics… nor do I need critics’ certificates. Only, I feel bad about the neglect that fiction suffers from.

SUKRITA: You think the creativity of the fiction writer is affected due to inadequate critical attention?

QURRATULAIN HYDER: Yes, indeed. The wrong kind of approach, coterie mentality and coterie politics which promote bad and mediocre literature can do a lot of harm. I have mentioned, a number of times, really outstanding fiction writers in my own writing and in interviews. Many people have not even heard of them, but there’s never a follow-up. No-one asks me who they were, what they wrote, etc. In Urdu, there is a strong tendency to attach one’s self to a single writer. For example a critic will start what he calls specializing on one writer, say, Premchand – he’ll go on writing about him, his characters, bulls in his fiction, his village. ‘Everything else in literature pales. His total devotion to Premchand blinds him to everything else. Another one may be devoted to Iqbal, and yet another perhaps to modern poetry. I think this amounts to taking an easy way out.

SUKRITA: Is this a reflection of the complex diversity of our Indian society, wherein each great writer constitutes a category in himself? The diversification of concerns and the multiplicity of perspectives, the exposure to a variety of cultures and religions down the ages on the one hand, and on the other, the reception of technology and ‘progress–oriented’ modern civilization? In the west, movements and categories are used to classify writers – the literature of cruelty, of silence…while here, it becomes far more difficult to ‘group’ writers.

QURRATULAIN HYDER: But what I’d like to emphasize strongly is the lack of original thinking in critical writing here. It’s so repetitive. The Progressive Movement began in 1936 and till today they are busy writing reports rather than criticism, producing surveys. This goes on year after year.

There is no criticism worth its name and the thinking is so confused. For instance, the same writers who made such a laudatory hoo-ha about abstract and symbolistic writing ten years ago are now condemning it. It was supposedly a revolution in Urdu fiction and all earlier writing was rejected as backward and stupid. A lot of bad stories were recognized as real intellectual thinking, real inner life, etc. All those clichés were used for stories which were not even riddles – riddles can be much more interesting. The point is that there is no clear thinking and perhaps there is no clearly developed critical faculty.

***

NIRMAL VERMA: ON THE MODERN SHORT STORY IN HINDI

![]()

Padma Bhushan, Sahitya Akademi Fellow, Jnanpith awardee and Chevalier de l’ordre des arts et des lettres NIRMAL VERMA (1929-2005) took his Master’s degree in History from St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. In 1959, on the invitation of the Czechoslovak Oriental Institute, Verma went to Prague for a decade, to translate modern Czech authors into Hindi. In short order he published not only translations of three Czech novels, two collections of short stories, and a play, but also his own first novel Ve Din (Those Days) in 1964, a collection of short stories called Jalti Jhari (The Burning Bush) in 1965, and several volumes of travelogues and reminiscences. After his return to India he served as Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study in Shimla to explore mythic consciousness in literature. He was invited to the Iowa International Writing Programme in 1977.

Verma has been as prolific as he has influential. Sixteen collections of short stories, nine novels, eleven collections of essays, three autobiographical works, and a play by him are currently in print and housed in the American Library of Congress as significant world literature. His work has been translated and published by Oxford University Press, Penguin, Readers International, Indialog, and Orient Blackswan, among others; his oeuvre is critical material for any university-level appreciation of Hindi literature.

He was also a career activist: starting with Gandhi’s prayer meetings through 1947-48 and via membership of the Communist Party of India till 1956 – when he resigned following the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary. His work is formally modernist – twentieth-century loneliness is his central theme, and his preoccupation with form is legendary. Verma is credited with pioneering the ‘nayi kahani’ (new story) in Hindi. But the delicacy of touch with which he examines the vulnerabilities of the human condition is more closely aligned with the work of continental and British writers of the nineteenth century too…

SUKRITA: Going through the gamut of short stories written in Hindi over the past several decades, one cannot help concluding that a lot of them have been written with a different orientation from earlier fiction in Hindi, perhaps through the influence of the modernist wave arriving from the west. But literary criticism does not seem to be directed at sorting out any of the basic critical questions that arise from an orientation that involves an interaction between two cultures. To what extent is the writer able to locate her own native cultural identity? And how does she imbibe the influences from the west – is that at the cost of her own Indian psyche? And lastly, would you agree that a much more conscious and concerted critical effort is required for the evaluation of modern literature in Hindi?

NIRMAL VERMA: I totally agree that there hasn’t been any focussed critical attention given to this issue. The authentic, indigenous contribution of a short story writer and what kind of exposure the writer has had to western writing, unconsciously and at times rather indiscriminately, are important features that have not been formulated or identified clearly by critics in Hindi. I think the reason is that for a long time ‘influences’ have been regarded very suspiciously, and somehow much criticism of contemporary Indian writing is aimed at proving that even the best of it is derivative. Whether our writing has indeed become a mere exercise in imitation or, as you’ve just said, there is a very creative sort of a confluence of the native and western sensibility in evidence, has not been worked out. This has obviously led to the impoverishment of the Indian critical scene. Perhaps I ought not to broadly say ‘Indian’ but then, as my friends from Karnataka, Bengal, or Maharashtra say the situation is not very different in Kannada, Bengali, or Marathi. What I do wonder, though, why you should feel it necessary to talk to the writers at all; you can always go to their works which I’d say are more eloquent than the writers themselves who may in fact mislead you.

SUKRITA: Because I think it’s important to see what some of the perceptive critics and writers consciously think about the questions I’m raising. Since there isn’t a specific tradition that might give one perspective on the evaluation of modern Hindi literature, the teamwork involved with these interviews, the dialogue about styles and subjects, helps me be more objective and to determine how conscious or self-conscious writers of the subcontinent are, about western borrowings.

For you — the characters of your short stories are not specifically related to a nation or a culture; they could be living anywhere in the world and do not seem to call for any situational localization. They could belong to any country. And the relationships, whether in Parinde or Andhere mein, are displaced relationships with a kind of quaintness about them. There is very little dialogue to reveal their psyche. However, you create an atmosphere in each story that matches the psychic uprootedness of the characters. In Parinde it is the mountains that give the story its atmosphere, not Shimla the city. Is modernity responsible for the deeper connections characters seem to have with the elements – with the mountains – than with each other? Does the story acquire a more universal character, somehow, through this kind of representation?

NIRMAL VERMA: This is a very interesting point. Writers are sometimes not aware of what pattern or quality of life emerges from their work. I’d say many of my stories are a reflection of the Indian middle-class milieu, and some of the silences are an integral part of the inarticulate suffering of middle-class individuals in our society. So much of the inner anguish articulated in western, word-oriented societies becomes inevitably muffled and convoluted through indirectness in the Indian context. For example, if a girl is in love with a person she is not able to make this feeling coherent, either to her own self or to another person.

Second, the point you have made regarding the elements. I’d rather put it this way – I feel deeply fascinated by the invisible relationship between the action of the story and its ambiance, where it is taking place, and the process through which a larger relationship is established, not merely amongst the individuals in the story but between the individuals and something non-human. The mountains in Parinde, a certain climate, a certain time of the year, say the autumn – these are things to which I always like to relate myself as well as my characters, maybe to feel emotionally secure as to the particular situation of the story’s dramatic trajectory. So, as far as I’m able to formulate it coherently, a sort of unspecific, invisible but very sensuous and tangible, environment in which the characters are operating – whether it is the mountains or the cityscape or season – is imperative. Specific localities aren’t important, but their particularities and peculiarities are. This is what particularizes the situation, and that seems to give a story its universal dimension.

SUKRITA: The story, then, is not confined within political boundaries, nor are any geographical limits established.

NIRMAL VERMA: Let me just add one thing – sometimes I feel very fascinated by it – this feeling of being cramped within individual relationships has another counterpoint in some of my stories, where this extra-human dimension, this non-human provides an experience of tremendous relief to the characters. They feel that even though there may not be a way out of the tangled tender relationships, there is something much bigger than them – the infinity of the skies, the continuity – the eternal continuity – of certain things around them. Those things stand as a counterpoint to something that is happening in a very immediate human context.

SUKRITA: Yes! I did note, as a reader, that the relatedness between characters and elements seems to bring about a kind of harmony to the situation and the tension in human relationships seems to get resolved, lending a sense of relief and a psychological equilibrium.

NIRMAL VERMA: Also, I’d say, it gives perspective.

SUKRITA: Which brings me to the impact of the short story on the reader. Let us speak of Indian readers in particular – obviously at some level you are conscious of the kind of readership you have. There appears to be a wide gap between the writer’s and the Indian reader’s measure of understanding and awareness. The writer is of course often ahead of her time. Even so, she does desire, not recognition, but some immediate response from the reader. What is your experience as a writer in India where a large percentage of people are not able to respond to what is called ‘modern literature’? The consensus seems to be that modern literature is sometimes perhaps abusively modern. How do you respond to this attitude? And how does it affect your writing?

NIRMAL VERMA: It is easy to answer this question because in India we who claim to be educated get accustomed to living or working in a self-created insularity. This can be very frustrating for a writer who is trying to get readers to see or feel past their insularity. The problem is greater than the writer not being able to get a response. It is a sociological problem. One is so conditioned to insularity after a while one stops feeling bothered by it and thinking about whether this is healthy or unhealthy. I do think that this has vast, disturbing implications but I shall not go into them now. However, I’d like to emphasize another point – that my literature or anything that gives meaning to one’s existence, or whatever matters to one – you can’t share those things with many people, so you get intuitively attached to the coterie of those with whom you can. People – friends, fellow-writers or readers – who are responding to you. This can work out to be negative. You feel so frustrated by the critics that you stop taking notice of them because you feel that their criticism or appreciation is so off the mark you don’t feel flattered or happy even if they say anything good, nor do you feel dejected if criticized. But that means you stop listening to anyone outside a small group – and that too is insularity.

SUKRITA: I’d say that young writers in India need extraordinary perseverance to sustain their efforts in light of the discomfiture of an unsympathetic critical atmosphere. We may in fact be losing a lot of genuine writers in the process.

NIRMAL VERMA: Sure, sometimes that is what causes a rather late maturity or an early death for writers. This is a sociological problem again. The creative exchange between an alert readership and the writer or between critics and the writer can make a world of difference.

*********

Text © Sukrita Paul Kumar

A well-known poet and critic, Sukrita Paul Kumar was born and brought up in Kenya. She was formerly the Aruna Asaf Ali Chair at Delhi University. An ex-Fellow of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, she was an invited poet at the International Writing Programme, Iowa, USA & Hong Kong Baptist University. Honorary faculty, Durrell Centre at Corfu, Greece, she has been a recipient of many prestigious fellowships and residencies. Her recent collections of poems are Country Drive, Dream Catcher, Untitled and Poems Come Home (with Hindustani translations by Gulzar). Amongst her critical books are Narrating Partition and Conversations on Modernism. Her translations include the book Nude, poems by Vishal Bhardwaj and the novel, Blind. A guest editor of journals such as Manoa (Hawaii) and Muse India, she has held exhibitions of her paintings. Many of her poems come out of her experience of working with the homeless, the street children and Tsunami victims.

————-

Sukrita Paul Kumar in The Beacon

Leave a Reply