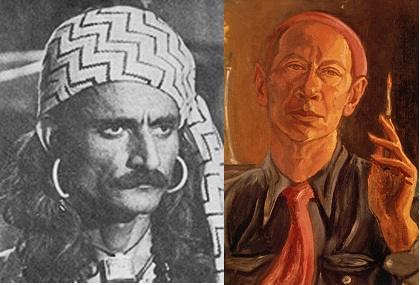

Self portrait. ee cummings. Getty images.

Geeta Patel

(with the help of Kath Weston)

In honour of S.R. Faruqi, my mentor and maestro and Kath’s pal

A Prelude

The Urdu Modernist poet Miraji (Sana Ullah Daar) lived from 1912-1949, was arguably one of the most inventive, theoretically nuanced prose masters and lyricists in colonial South Asia. His prodigious outpourings included essays and translations on poetry, on other poets. What marked him out were his closely parsed dense readings of his own compatriots and his open ended renderings of verse culled from poets who lived in other times and places that came to his notice via books in libraries he haunted assiduously as his ‘archives of belonging’ to misquote Susan Sontag

One such poet he ‘discovered’ was e.e. cumminhgs (1894-1962), American poet, painter, playwright, essayist, whose free-form poetry, idiosyncratic syntax probably appealed to this idiosyncratic Urdu modernist. Miraji read one of cummings’ poems, reproduced below, and rendered it into Urdu.

In turn I read Miraji’s rendition of ‘may I feel said he’ and offer my own rendition into English. I stayed true to how Miraji translates, which meant that I could tinker and fiddle around with his translation. Staying true to rather than literal, frees translation to its most sinuous possibilities.

**

e.e. cummings

may i feel said he

may i feel said he

(i’ll squeal said she

just once said he)

it’s fun said she

(may i touch said he

how much said she

a lot said he)

why not said she

(let’s go said he

not too far said she

what’s too far said he

where you are said she)

may i stay said he

which way said she

like this said he

if you kiss said she

may i move said he

is it love said she)

if you’re willing said he

(but you’re killing said she

but it’s life said he

but your wife said she

now said he)

ow said she

(tiptop said he

don’t stop said she

oh no said he)

go slow said she

(cccome? said he

ummm said she)

you’re divine! said he

(you are Mine said she

![]()

![]()

![]()

Miraji

Tease

What remains

Just look at her:

You’re so tender

You’re so fierce

Turn to me:

You’re so cheeky

And you can see:

Don’t withdraw, come listen

This is what I saw: Come over, just

listen

Should I see it so: Go away, why won’t you listen

I see this: Do what I ask

Diddle, dither and dawdle, let me

Oh god, take me.

Tease

You’re so tender

You’re so fierce

You’re so cheeky

Don’t withdraw, come listen

Come over, just listen

Go away, why won’t you listen

Do what I ask

Diddle, dawdle, dither, let me

Oh god, take me.

An Afterword

The Urdu Modernist poet Miraji (Sana Ullah Daar) lived from 1912-1949, and was arguably one of the most inventive, novel, theoretically nuanced prose masters and lyricists in colonial South Asia. His essays and translations on poetry, on other poets, his closely parsed dense readings of his own compatriots and his open ended renderings of verse culled from poets who lived in other times and places, that came to his notice via books shipped over to sit in libraries he haunted assiduously, tested even those who shared his modernist sensibilities.

Miraji paid for it by being tossed out of literary circles, accused of sexual shenanigans and perversions, though he was one of the many who brought together a cluster of poets under Halqa-e arbab-e zauq (the circle of the men of taste). Translation for Miraji was a political practice out of which Modernism was forged – he understood that Urdu had forgone its tongue, dropped aside the pleasures of singing about love under British auspices that promulgated, as a genre of governance, a refashioned lexicon and themes for poetry. Much of this was under pressure to translate from properly demarcated English literature into Urdu to bend poetics into something new, focusing its gaze away from the metaphorically luxuriant landscapes of love and attuning it instead to naturalism, or a touch closer to literalist versification. So Miraji chose carefully to torque translation to insubordinate ends—winnowing poets who could not be easily absorbed into propriety whom he then proceeded to translate and use as his theoretical lodestones for refashioning poetic craft itself. Some of those he translated, such as the French Symbolists, were also translated into other South Asian languages, but others, such as e.e. cummings and Sappho, were rarer.

Miraji was an unfailingly playful translator. His maqsad, purpose, was to make the ‘original’ something other than it might have been imagined to be, so that when you read the so-called original it felt as though it was the translation of Miraji’s ‘original.’ But Miraji’s translations did not stay still, they wavered, waffled, wiggled on their seats as they became Miraji’s – and CheD is one such example. CheD is a translation of “may I feel said he” by the poet e.e. cummings. Miraji took cummings and something else came forth in CheD. cummings crafted a mischievous to-ing and fro-ing, the tug and pull that turned yearning into flesh. Miraji composed it into something else, not quite entirely, but with possibilities that Cumming’s lyric didn’t hold in the same way. Now, it could be a guftagu between two people who are playing through eager craving, desire, reaching out, but it could also be a translator’s benediction or curse, their kashma kash as they sift phrases through their pen, each scribble longing, lingering, a line pulled towards or away from another possible syllable.

The simple, spare edition of CheD from Sah Aatishah is what I first happened upon when I was in Mumbai tracing Miraji’s journeys. Sah Aatishah was gifted to me by Akhtarul Iman, pulled out of the sagging thaila, cloth bag, in which so many of Miraji’s manuscripts had found their home. By Miraji’s own account CheD was translated from e.e. cummings, during Miraji’s sojourn in Delhi, somewhere between 1942-1946, when Miraji was working for All India Radio, changing their lyrical soundscape by reading translations of poets from all around the world on the air. Included as it is in his roster of his own lyric, CheD becomes Miraji’s, dropping cummings along the way. The longer version is in the published edition of Sah Aatishah [with fire] (114-115) and shorter in the published version of Tiin Rang [three tones] (110-111).

I have stayed true to how Miraji translates, which meant that I could tinker and fiddle around with his translation. Staying true to rather than literal, frees translation to its most sinuous possibilities. My renditions jostle between the cummings and Miraji’s and repeat rhythmically rather than merely rhyme, so that my English torques all the ‘originals’ breaching each quite deliberately. My translations also mess around with spacing, so that they read vertically as well as horizontally. The longer version by Miraji brings in the tonalities of the ‘she said’ ‘he said’ and in doing so echoes the cummings. This one is probably meant to be read on the page, desire measured out in the stripped phrasing is filled with cues that orient a reader as to who is speaking and whether the words are imagined or spoken. In the briefer one, the cues are peeled away and the conversation, standing on its own, only comes alive when it is read aloud

One unexpected major distinction between cummings and Miraji is that Miraji exploited the grammatical conventions of Urdu, held his lyrical renditions tightly to the semiotics of pronouns in oblique, which allowed Miraji to evade gender entirely; his account is more open, amenable to whomsoever wants to place themselves in the lyric, to which I have also tried to stay true. This capaciousness is much harder to hold onto in the longer ‘cued-in’ one when I turn it back into English, so I must say, as a translator, the more succinct one is closer to my heart. However, as a caveat, I would like to add that in the longer one I use the ‘I’ without a gender, and there is no reason why the ‘she’ could not have been a trans person, or a woman if one doesn’t believe that. Leaving the ‘I’ unfurnished in this way also allows CheD to easily belong to the oeuvre of poems and curve and frolic and ‘tease’ out the flesh and foment of desire in all its keys, from rambunctious joy to fierce agony to stilled composure, whether those poems came from translations that Miraji composed and left under the name of the poet from which he pulled them, or those that he turned into his own, or those that have no discernable antecedents.

If one puts CheD into this lineage, has it speak across oceanic expanses, it could so easily have been one that Sappho sang to her lover Attis, tacked onto the lyric by Sappho that Miraji tuned into its most capacious and sprawling form in his essay on her.

******

Geeta Patel is Professor at University of Virginia’s Department of Middle Eastern &South Asian Language and Cultures. Her work spans gender, colonial history, poetry, feminism. She holds three degrees in science and straddles an interdisciplinary world of science, finance, cinema and media as well. Some of her notable publications include Lyrical Movements, Historical Hauntings on the Urdu poet Miraji and Risky Bodies and Techno-Intimacy.

Geeta Patel on Miraji in The Beacon

Unforeseen Poet: How I found myself in lyric

Queer Hauntings of a Vagrant Heart: Miraji’s Poetic Visions

More by Geeta Patel in The Beacon

Portraits of Unspeakable Anguish

Leave a Reply