Geeta Patel

Introduction

“We shall not cease from exploration…” T.S. Eliot

B

orn in 1912, Miraji who died in 1949, was voluptuously synaesthetic, an exquisitely philosophical poet in Urdu, an avid translator, a voracious essayist, and an edgily incisive, attuned, empathetic, remarkably generous reader. Of Miraji one could say, following most appraisals of his capacious and sometimes startling interventions in both lyric and criticism, that he augured a new strain of Urdu modernism in the cauldron of anti-colonial politics.

Even as Miraji was juggling accolades for lyrical feats, he was also fending off excoriations that followed his portrayals, widely circulated, as an opaque, enigmatic versifier and a supposed sexual pervert. Though many of the questions Miraji fostered sifted through the semantics of solitude, he rarely worked alone preferring the intellectual camaraderie of those who shared a sense of the times. Miraji saw poetics always in concert with fellow artists, his hamsafar—’adab nigār.

By the time he died, on the electroshock therapy table in a Bombay (Mumbai) hospital on November 3rd, seventy years ago, Miraji had, in his short life, published prose and lyric in many journals of the time, printed several volumes of poetry, one small volume of essays on his fellow lyricists, a substantial tome on poets ranging from the Bronte sisters, Li Po, Japanese and Korean women poets to Charles Baudelaire and Stéfane Mallarmé, Chandidas, Vidyapati and many others, a new translation of a Sanskrit sexual treatise, and was assiduously honing another collection of his own lyric as well as compilations of Mirabai and Omar Khayyam.

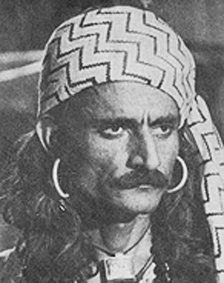

Miraji was born in Lahore on May 25th, moved quickly to Baroda with his father who was a railway engineer,returned to the vibrant poetic scene in Lahore to complete school, worked at All India Radio in Delhi and traveled onto Bombay with many Urdu writers to find his way, as all of them (including Saadat Hasan Manto) did, in the film industry. Miraji was a consummate poet of the streets, someone whose life was made replete through the journeys he took. Photographs bring him to life as a sādhū, mala in hand, long hair untamed, earrings dangling. One can almost imagine him, his thailā or shoulder bag laden with books and loose pages scribbled full of poems, a small bottle of alcohol tucked between them, wending his way on a yatra. He could have been a typical ‘āshiq, a lover, hollow-eyed, locks askew, bechain, swinging between hope and despair, haunting the street, awaiting a glimpse of the woman he said he loved, Mira Sen, whose name he may have taken on, outside her firmly closed door, loitering outside Kinnaird College in Lahore. As he describes in his nazm, “Ānkh micholī”:

“I walk past my house a little,

wish she were here.

How quickly she eludes my glance.

What must I believe? Does she abhor me?

But this: she looked down so soon, in such silence.

What can I believe, does she know my longing? And

this?

When our eyes meet, she shuts her door, and I,

destitute,

wander again.”

But Miraji was a poet of the streets in many less conventional ways. If one can imagine galiyān as poetic paths, he also haunted the byways of libraries while he was still in school, picking and culling, and commencing conversations with the writers he read and through them with the artists with whom he lived in a more mundane fashion. He had forsaken a conventional education and was entirely self-taught. The librarian at the Punjab Public library remembered him as the first one in and the last one out. Libraries became his avenues to other worlds, avenues he travelled inexorably, returning to Urdu from sojourns into translations from English, French, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and, closer to home, from Bengali, Bhojpuri, Maithili, Sanskrit, and Braj.

“…and the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started…” T.S. Eliot

In absolutely essential ways these journeys transformed his being, became the lodestone for his poetry. He was then, as so much of his poetry shows us, a musāfir, a traveler, who tuned into all these languages as well as Arabic and Farsi, sufiyana and bhakti mysticism to compose—whether these were the more easily accessible Gīt and pāband nazm or the more bricolage style, cryptic free verse.

Miraji was very young when he wrote many of his essays on poetry that he could have encountered only through such “travels”; some of them, collected in Mashriq-o-Maghrib ke Naghmain, were composed when he was 18 years old. He began to experiment with lyric while he was a child under the penname “Sāharī” (enchanter), and went on, while he was in Lahore to strengthen a local symposium of poets and writers along with N.M. Rashid, the Halqa e Arbāb e zauq (the circle of the men of taste). His determined insistence on cohabiting lyrically with his poetic circle carried on and sustained him until his death.

When he died, his friend, the poet Akhtar-ul-Iman mourned that only four people came to carry his janāzah, his lāsh to an unnamed grave, buried deep in a graveyard with the Mumbai suburban trains rattling by.

******

I

Enigma of the Polyphonic Gaze

Q

ueer. In Urdu the word gazes in two directions, invokes two meanings. Strange, anomalous, something that provokes curiosity, the magical, the marvelous, which pushes back the edges of the everyday: these come from ‘ajab, to wonder. When one points out someone or something as ajeeb in a passing comment, they might imply peculiar, a touch mad, foolish or silly, or just a tiny bit odd, flouting conventions slightly: as in pāgal sā. Queer then is both ajeeb and paagal saa; it loiters almost insouciantly in between, not lingering for very long in either: lounging a little off-center,a tad Terhā, looking askance in both directions, between the Arabic root and a common word perhaps taken from Sanskrit in a lineage long faded from view.

Queer Miraji. Miraji the poet, essayist and reader His creative visions an odd assortment of sweets on a plate that one looks at longingly, to taste: to offer as an incitement to conversation. Savour this, a re-translation of Swinburne’ s elegy for Baudelaire from Miraji’s Urdu version of the original English version:

“Ave Atque Vale”

Oh my brother

in the old season of your songs,

you saw in those secrets, in that grief, in that

anguish,

which is denied us,

the harsh tautness of love’s knife flame.

At a place at night

where no one has dared breathe till now

the petals of sweet love’s poisonous buds

bloomed for your delicate gaze.

No one else even glimpsed them.

The secret treasure of time’s ripe fertility

its faults which have no astronomy

those things leached clean of happiness,

two places, where with the eyes of a grieving

soul

as it turns in sleep, turns from the dust motes

of strange dreams and weeps,

on each face you glimpsed a shadow so

you saw that what people gather in a garden

blooms/flowers only as thorn.

Consider Miraji’s synoptic biographical details— where he lived, died, what he wrote, who he was to Urdu poetics.You might not know the stories that explain his name; the entanglements with Mirabai, the bhakti poet because in some important ways, the sliding across names suggests a kind of intimacy with Mirabai, an intimacy that Miraji pursued in his writing. So the mistaken name continues to be odd in a somewhat useful way, to be sort of queer.

And, as always, it provides a space for questions of gender in many different keys. When I say queer I mean something quite specific: the lineaments, the flesh, sinews and muscles of a field that has come to be called queer theory. Many popular perceptions of queer theory imagine that it attends to identities in the present or the past — and it opens those identities up to include subjects who stretch the frame beyond gay and lesbian, and of course, beyond heterosexuality. Is queer theory, then, about sifting through archives of the present, unravelling moments from the past to find instances of various practices and figures such as these? Yes, but that is not just what it does.

Anthropologists such as Kath Weston, who have written on sexuality, call this mode of investigation salvage anthropology: traipsing off to ancient and contemporary sites in a literal and not so obvious fashion to salvage objects that recuperate people who had complex desires, or to pursue stories that bring non-heterosexual desires to view.

Newer analyses that take their cue from queer theory, such as Weston’s and those by South Asian scholars such as Anjali Arondekar, or by Lauren Berlant, Jose Munoz, David Eng and Andrea Smith, among others, style queer theory through practices of reading, rendering narratives, poetics, politics, lyric tender, vulnerable, fierce, so that in feeling them this way other ways of being might flower into sight.

Readings that incline towards crookedness, vakroktī, Terhā, Paichīdā, twisted, turned, playful. From this sense of queer we get crossing over, crossing gender, cross-dressing, playing with what one is or what one does, playing against the grain of easily settled readings, of poetry, personalities, māhaul or world.

Queer, then, is not a mode that brings to light, illuminates in a transparent fashion. To the contrary, queer readings celebrate the unfinished. They keep alive the possibility that when something is deciphered some small piece will escape or evade clarity, will remain obscure.

When we queer something, as Jacques Derrida would have said, we invoke the undecidable, the supplement that resides between sated fulfilment and hungry impoverishment. For Miraji, queer might be found when lyric finds its flesh in the language of passing conversations that seem to stage everyday lucidity even as verse reaches for the ambiguous or the elliptical, ibhām and mubham. Something is left unsaid, left behind, left to be sought again, left to twirl towards what yet remains adhurā, namukkamal.

Sāre rind aubāsh jahān ke tujh se sujūd main rahte hain

Bānke terhe tirche tīkhe sab kā tujhe imām kiyā

(All the skeptics, reprobates, libertines, rakes, blackguards, mobs, live prostrated before you Cunning and fraudulent, crooked, bent and awry, perverse yet foolish, piquant. You’ve been anointed to lead them all.)

Mir Taqi Mir’s verse is so apt a description of Miraji; one that so many critics writing about Urdu might resort to, however obliquely, when they talk about his life and his lyric. And that commonplace sense of who Miraji was lends itself to considering him through queerness. View Miraji as the Imaam of the rind, aubash, bānke, terhay, tirche, and one might glimpse things a different way, askew as it were.

Perhaps appreciate gender, and even women, in a perverse key.

The afsaneh and hikāyat that draw portraits of Miraji blur because they superimpose impossibly contrary photographic negatives. You get Saadat Hasan Manto’s dialectic, kash-ma-kash, pull and tug between the faqir, the wandering Sufi bhakt on a safar which never arrives at stillness, and the contemporary Āvārā soaked in the nightly liquor Miraji consumed so copiously. You get a figure crowned in a jat, garlanded in a mālā, speaking the voice of nazm. While by the poet’s own account, in the aptly named Namukkamal self-portrait, he was pulled willy-nilly into poetry through desire coursing through skin. Three incidents in that piece stage a paagal-saa sexual deviant in the medical terminology so many of his compatriots used to describe him.

All three invoke the tender, curious vulnerable gaze of a young boy absorbing scenes soaked in desire and they allude to the angles Miraji’s poetry will take; they map a few chosen moments along its journey. Monsoon rivulets chalking Pavagarh in Halol, begetting the sinuous temptation of a snake and Adam and Eve’s craving to mind. A young girl peeing, a moment that brings nature into focus as moral ambivalence: the moment is tucked into a game of hunting, with Bhils flushing animals out towards a child playing at British hunters.

A dream in the half-woken light shadowing the tender nubile outline of a child: a stolen vision that Miraji says inhabits his poetry as clothing, as fetish. Unseemly, baanke and queer. Not an adult desire, but a child’s — and in this, reminiscent of what Ismat Chughtai also explored, in an oblique conversation with Sigmund Freud’s Three Essays on Sexuality.

Māsūm, longing, birthing lyric in three literalised allegories. In other words, utterly queer. Here truth is not what is at stake, and the problem with Miraji was that he always eluded the impossible call to find out the real truth. But self-fashioning is. Because his essay never culminates in a fully fashioned portrayal: it remains adhurā, refusing the comfort of convention.

But then, to lay against the quite explicitly young boy’s gaze that Miraji gives himself in his self-portrait, there was the paradoxical question of his name. Miraji was born Sanaullah Daar. Poets don names under which they compose, sing, recite,write. Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib changed his name from Asad to Ghalib. Alam Muzaffarnagari (1901- 1969), born Muhammad Ishaaq, took his name from the city of his birth. Such poetic names may make some kind of commonplace sense.

Miraji was unusual in that his name changes provoked stories recited by friends who, despite every biographical tale they might have produced, struggled to make sense of the routes Miraji travelled to arrive at his nom de plume.

Miraji’s first penname was Sāharī, one that he took when he was a young man in Lahore finding his way as a poet. Its meanings — enchantment, magic, sorcery, necromancy, from saahir, from the root s-h-r, which in its turn means turn from its course — suggest an ontological and epistemological magic trick, a sleight of hand, a world of wonder (he called his room saahir khaana, the enchanted room, the sorcerer’s abode).

Miraji, his second name, under which he lived after he began to use it, also incites stories that attempt to unravel the mystery of ‘why?’ He did not just use it as a penname: he began to live under a woman’s name. And in following the spoor of the names, the stories of how Miraji came by his name, I track between two narratives in my book on him.

![]()

One story turns its gaze on the young woman, Mira Sen, whom he caught glimpses of in Lahore as a very young man, and was supposed to be madly in love with and whose name he absorbed. The other suggests the poet Mirabai as an inspiration. As with everything else about Miraji, the story of ‘how he got his name’ never resolved itself. Queer Miraji…loitering insouciantly between ajeeb and paagal saa?

Composing as Mira, living as Mira? Epistemology, ontology, politics. So composing as Mira is an utterly familiar act. Taking on the position / place of a woman, singing in the lyrical musical voice of a gopi, of Radha, Krishna’s lover, of Radha’s sakhī or friends allows many poets pathways into sringāra rasa, the vehicles or routes to live the wrenching sorrow of unfaithful love, to flesh the willful dancing joy of meeting a lover surreptitiously in a dense moon-lit forest landscape of aesthetic composition.

Singers translate themselves into another voice, without forsaking their own. In other words, men, women and transgender singers become women as they sing. And Miraji, translating love lyric from Bangla, from the poet Vidyapati, is familiar with the practices of living as a woman, especially if one is lost in a frenzied longing for Krishna. And of course there is Rekhtī, another vehicle into Urdu, love sung in a woman’s voice to another woman, often in voluptuously erotic phrasings; 18th and 19th century poets such as Sa’adat Yar Khan ‘Rangin’ and Insha Allah Khan ‘Insha’ are familiar exponents.

In lineages of lyric composition, then one is not born a woman, but enters into being one. And this is queer. Not the simple voicing as another, or even living as another, but noticing what those instances of becoming something else might entail. Something familiar looked at askance, in a terhā, ‘ajīb way.

All I have in my possession of Miraji’s translations of Mirabai’s poetry is the frontispiece of the book in his own hand — he called the book Miranjalī. Anjalī as in offering, gifted by Miraji as Mira, for Mira, to Mira, by Mira. Miranjalī cusps the closure between the name and the noun, suggesting water poured out from hands: an appropriate title not just for these translations but for the way translated voices figure in his lyric.

“The mind was dreaming. The world was its dream” Jorge Luis Borges

Gender as an aesthetic device has another valence in the last stages of colonialism; it becomes a political proxy through which writers from the Progressive Writers’ Association are expected to compose. In other words, the rhetoric of the PWA follows a long lineage, which begins with South Asian responses to 19th century British critiques of South Asia, of imagining new futures for decolonisation where those futures are committed to better lives for communities fated to violence, mired in histories of containment and deprivation. Women are centrally featured, as are workers, villagers, farmers. The rhetorical, epistemological and aesthetic intent is ensconced in graphic literary compositions and mirror or illustrate the depredations of failed lives as pathways to understanding them; their betterment, their taraqqi, is yoked to the project of building a nation that attends to those lives in a meaningful way.

Miraji thought differently. For him, a writer who occupies, takes over, voices from these communities to compose a story, succeeds in closing them off precisely because the thread of representational possibilities is shot through with the shades of colonial representations.

Speaking only of violence and deprivation is a foreclosure bound into a long history in British appraisals of South Asian treatment of women.

Many of Miraji’s projects of translation are overtures in tightly orchestrated scorings of representational possibilities for gender.

Translations for him were auguries from other modulations for composition: Japanese women writers, Korean women writers, to Sappho and contemporary women poets from Europe. And Miraji took his cue from the armature of prior inclinations of composition by writing as a woman, writing the gendered gaze, writing for a gendered gaze.

Here’s Miraji gazing at Sappho’s lyric:

Prophecy

After my life has come and gone, perhaps

A spring flurry may waft in, so

A voice rebounds, echoing

My songs heard the world over.In world of sorrow dusted with agony

I live, subsist in a semblance of loss

as though the wind’s lament wafts my tale of love onwards

and callous malice bequeaths no traces.Love’s shackles

Passion tethered me

Rebellious terror brought me to my knees

Bitterness steeped in the clarity of milk

Tyranny escorted by kindness

I come to see love’s respite in every heart’s ordeal

Attis has left me

bound her soul to a stranger.Turbulence

We see in love’s remains

Flesh and spirit flinching in terror

As though the whorls of a tempest

Were shrubs,

Juddering, tucked deep in hill groves.

Miraji had secured a perch in the aesthetic politics of his time. But the way he dwelled in his landscapes established his foundational differences. terhā, a bit off, a bit queer; at odds with his own time.

So what was Miraji’s own andāz e bayān?

II

Lyric of Unfinished Longing

Miraji’s most unpredictable forays into lyric pass through nazm and though he wrote ghazal and gīt as well he was often accused of being nazm parast. Responding to the charge of an excessive fondness for nazm, Miraji said that its capriciousness gave it the capaciousness to accept idiosyncrasy. So nazm was an amenable vehicle for a poet such as him whose heart dallied like a yearning lover waiting awkwardly along the lineages of an earlier aesthetic even as his gaze was glued adamantly to his present circumstances.

Miraji’s nazms muse on a timbre, on the compass of a thought, on the crinkle of ambience—playing metaphors out until they stall. Though nazms that seem close to one another may almost show through each other as palimpsest, they never fuse into consistency. So Miraji’s corpus always feels slightly unfinished, a play that was on-going, as though another image might be waiting in the wings, another poem about to come on stage. This is particularly true of the voyages he made through gender, and it is here that seminal differences from the Progressive Writers’ Association lie.

Unlike many of his writer-compatriots in the 1940s, he did not route his aesthetic pathways via the usual failsafe makān o samān kām kāj, through the everyday errands that stalked domesticity and silhouetted women in the quotidian and often careless cruelties which fissured their lives to wrench their bodies towards gruesome, predestined outcomes. Instead, his politicallyricism wended its way through the philosophical nazm — its orientation not just towards the content, the meat and matter in the verse, but something else: Epistemology, questions of knowledge, the weird slants they might assume if they were channelled through gender.

Gender is not destination but a passageway into other questions; that journey is possible only if it abandons domesticity, runs away from home; turns uncanny.

Gender, in Miraji’s lyric, was never an alibi for representational politics but the domicile through which representation became murky, queer, angled and unforeseen. It was a dissonance from the rhetoric of the time and sealed its covenants through translation of lyrical forebearers.

Guided through sringāra, kāvya, the terse poignancy of Sappho or Japanese haiku, Miraji’s lyric could wax rhapsodic or torque into facsimiles on poetics; hunker down to love slipping away into anguish, seed itself where gender faded away. Desire could obey the covenants of commonplace expectation or elude them altogether.

Into ‘Ras kī anokhī lehren,’ Miraji, as a woman, siphons masarrat, savouring the plump tang of elation, happiness, delight. The nazm, a monologue, commences with a woman’s voice longing for herself:

main ye chāhatī hun ke duniyā kī ānkhen mujhe dekhtī jā’en

main ye chāhatī hun ki jhonke havā ke lipatte chalay jāyen mujh se

machalte hū’e, ched karte hū’e,

hanste, hanste koi bāt kahte hū’e

lāj ke bojh se rukte rukte,

sambhalte hū’e, ras kī rangīn sargoshiyon mein”

(I want gusts of wind to wrap themselves around me, pout, tease,laughingly say something, pause shyly, collect themselves in playful, juicy, passionate whispers).

The poem closes with the almost uncertain circle of joy (masarrat) into which she resolves. The refrain, “main ye chahati hun” — I desire this; I want this — orchestrates every verse. The second stanza clothes the speaker in a flurry of lively images:

“main ye chahati hun ki jhonke havaa kay lipatte chalay jayen mujh say /macalte huay, ched karte huay, hanstay, hanstay koi baat kahte huay,laaj ke bojh se rukte rukte, sambhalte huay, ras ki rangin sargoshiyon mein”

(I want gusts of wind to wrap themselves around me, pout, tease,laughingly say something, pause shyly, collect themselves in playful, juicy, passionate whispers).

A woman’s desire — what she wants from it for herself — welling in each segment out of an image palate awash in wind, tree, river, words soaked in tender sorcery. Never morphing completely into human substance or avatar, the lyric’s playful, whimsical voice thwarts and forestalls, confounding readers who might come to it expecting their gaze to sample and savour a beguiling fetish or an impoverished figure whose will has been dissipated by the violence of her circumstances. Written in 1942, the poem harkens instead to the fleshy iconography of nature from some of the Hindi lyric composed by Mahadevi Varma, the Chhayavad poet who was occasionally called a modern Mirabai.

In ‘Tahrīk’ Miraji douses the nazm in the tonal shades of sringāra rasa from Sanskrit kāvya and Braj geet, to service a voice bereft, denuded,emptied of gender. From your eyes to my heart, both are in possessive oblique, desire in disguise, gender withheld.

Unlike ‘Ras ki,’ readers of this nazm are never cued in by the poem’s grammar to the gender of the speaker or to whom the voice directs itself; anyone can live in its ambience, feed off its music.

The title which means movement, motion, impelling, agitation, syncopates against tariik, darkness, death, desire, and tariikh, history, time, chronicles: registers which shove the poem backwards through sultry scenes that echo bhajan, and forward, into the present, the season of this lyric’s poetic anguish. When time makes its appearances in the poem, it lingers in the tense of the perfect, the temporality of hagiography, of narrative, of myth, of suspension.

‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ and ‘Ba’ad ka udāv’ venture into slightly different terrains than either ‘Tahriik’ or ‘Rasa ki.’ Flitting between the pillars of a temple, a dancer’s body in ‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ summons a clandestine, furtive covetousness. Skimmed sar-e paa, top to bottom, perhaps by the pujari in the title, the devadasi’s skin metastasizes slowly, sensuously rippling through an inventory of jungle dwellers. The second poem in his collection Mīrājī kī Nazmain, ‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ was written between 1932-1934. Miraji was just about 20 when he composed it.

‘Ba’ad ka udav,’ written later, in 1941, offers its provocations through stories left strewn with clothes in the wake of a night’s pleasure, bringing into the poem’s bedroom landscape an Old Testament lineage: the crow who glimpses land at the far reaches of the flood which sent Noah fleeing into the ark.

Despite their obviously dissimilar locales, the two poems share something crucial — both hint at the salacious scrutiny of a woman by a woman. A reader passing into the poems’ custody, enmeshed in desire, is dragged willy-nilly into becoming, for even a small space, a small opening in the poem’s time scape, a woman looking—at odds with the putative gender of each poem’s protagonist.

This, as I have intimated in Lyrical Movements, Historical Hauntings, upends the implicit proprieties of a reader’s assumptions, makes readers so uncomfortable with Miraji’s lyrical practice that they are willing to repudiate his entire oeuvre; they are willing to toss his entire corpus into the dustbin of literary history.

‘Ba’ad ka udav’ rollicks with unanticipated scenes:

bikhere hū’e hain gesū /

bindī dumdar sitārah hai /

magar sakīn hai /

chalte, chalte ko’ī ruk jā’e achānak jaise /

Ghusal khāne mein nazar āyā thā, unglī pe mujhe surkh nishān /

vahī dumdār sitāre kī numā’ish kā patah detā thā”

(Hair disheveled bindi a shooting star at rest as though someone paused unexpectedly while walking in the bathroom I saw a finger stained red that foretold the star’s arrival It passed by but left in its wake like a faint footprint on night’s path.)

As Mehr Farooqi has pointed out these lines conjure a woman looking at a woman

Unlike in the first stanza of the poem — whose final line establishes masculinity through the direct pronoun in the phrase “main hotā to yeh kahtā tujh se” while leaving open what the gender of “tujh” might be — the oblique pronoun “mujhe”of the second verse does something else. The stained finger, “mujhe surkh nishān,” the faint smear a bindi rubbed inadvertently while making love, leaves behind the residue of a woman looking at a woman.

‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ hailing readers, “Lo, nāch ye dekho,” come see this dance, summons them to contemplation. “Nāch, pavitra nāch ik devadāsī kā / dhīre, dhīre dūr hū’ā hai, sāyah mere dil se dil ki udāsī kā.”

Despondency slips away in these opening lines when they turn to possessive oblique pronoun we also see in ‘Tahriik’; and in doing so they stymie the assumption that the priest of the title carries along with him, that seduction can only be funneled through male eyes. The oblique “mere,” solicits anyone to come, occupy the “I.” And the shadows of gloom slide off a reader’s heart slowly, slowly as the metaphors buoy.

Looking turns into caressing an inventory of images that flash by. The poem courses through them. The philosophical question that surfaces as a reader vanishes into the poem’s skin is: what does poetry do?

‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ provokes another genre of recognition, where ontology fleshes epistemology, one that Miraji himself alluded to when picking out poems he considered good enough to parse for his collection Is Nazm Mein. Good enough poetry had one obligation — that it flaunt Khayālāt. In Is Nazm Mein he writes: “When I picked nazms I was attracted by those that were intellectual. Because, I believe that their real foundations lie in intellectual concerns. If a nazm did not address something new, did not take a few steps forward, then analysing it was pointless, was a waste.”

This is Miraji’s command to modernism: images, metaphors, allegories need to flesh out ideas. Poems such as ‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ are not merely about Jinsiyāt, about the nakedly carnal. Instead, they are reflections on what happens when a poem seduces a reader to submit to its world, to enter its skin and live with it, in it, fleetingly.

The poem gives readers a chance at sorcery, a mirage of what reading without completing a story might look like. We enter the Sāhar khānā, the queer world of Miraji; ‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī’ shows us how to read anew.

Who was Miraji as an adakar, performer, an actor, an artist? One might well go to the beginning of a nazm he wrote, titled ‘Adakar’. It is the culminating lyric in his collection, Mīrājī kī Nazmen. Earthy and ethereal, philosophical because it is embroiled in a corporeal repertoire, it draws from both his more Perso-Arabic and Braj-Hindi lyrical lexicons. Like some of the others noted above, it fuses the straight forward colloquialisms from everyday Urdu with the complex rhythms of literary Hindustani Farsi, Arabic prose and medieval mystic verse. Its phrases slide from the smooth ease of conversation to the thickly layered synaesthesia of multiple literary languages. Deceptively lucid, the poem’s rich imagistic universe seems to lend itself to easy comprehension, even as it travels a convoluted journey into a poet’s psyche.

Gudāz pattī keras ko ik pal mein chūs legī

Magar use yeh khabar nahīn hai har ek phūl ek — ek bhanvare ke dhyān men kho ke jhūmtā hai

Khile hū’e phūl ko jo dekhe yahī samajhtī hai uskī nakhat mere fasurdah mashām-e-jān ke liye banī hai

magar khilā phūl kis kā sāthī?

Jān ke liye banī hai magar khilā phūl kis kāsāthī?Main ik musāfir — chaton pe, dīvār-o-dar pe, dahlīz par basīrā rahā hai merā

Aur āj, rāste mein ā gayī (tū)

Yeh terā pardah ki jis ke us pār mujh ko dīvār-o-dar bhī, dahliz bhī, chaten bhī

Dikhā’ī detī hai khāk āludah āghī se

Kabhī to uthtā hai, uth ke girtā hai, gir ke uthtā hai — is kī larzish

Kabhī tabassum kabhī sukūn kī pukār ban kar

Mujhe bulātī hai phir ye kahtī hai chup —

Thahar jā’o dekho, shāyad koi yahīn

Dekhtā hai,lekin khiltā hū’ā phūl kis kā sāthī?

Us chaman se nahīn hai nisbat voh us jahān mein

Har ik ke hāthon se hote hote, kabhī kis sej pe, kabhī kissej se chitā tak

Pahunchtā, rahatā hai aulu zamānā

Pukārtā hai —khilā hū’ā phūl kis kā sāthī?(the following is the structure of the translation. You can add periods between the lines to make sure that the structure keeps true. My tongue tastes flowers like a shy gecko, as though It might suck a plump petal’s sap in an absent, hurried moment But it doesn’t know that each flower, one by one — sways in the dream of a bee. Anyone who looks at a flower budding open Believes that its intense perfume blooms only for their faded melancholic, numb life — reaching for a sense of smell, reaching out to scent. But for whom did this flower come to life, whose companion is it, who does it accompany?

I am a traveler, an itinerant, a nomad.

On roofs, along walls and at doors, at the threshold, I nest or roost, find repose

If you come by this path today, then

This is your curtain, your screen, on the far side of which I glimpse

Walls and doors, thresholds, and even roofs, dust tarnished insight, stained by ashes bequeathed from a fire. I get up sometimes only to fall, and when I fall, pull myself up again — its tremble, tremor

An occasional smile, a sudden call

Hails me, and says “quiet, stay silent” —wait a bit, perhaps someone Is gazing out here — but

Whose companion is a flower that once bloomed?

They don’t have a rapport with the garden, with that universe from which

Passed from hand to hand, sometimes supine on a bed, sometimes from bed to funeral pyre

A strange perturbed age arrives, to call out and ask.

Whose companion is a flower that once bloomed?)

So what does this poem tell us? In translating Miraji I follow his own protocols for tarjumah, take liberties with the rhythmic conventions of recitation in Urdu, repeating phrases so versions tug and jostle. And this poem, which is deliberately mubham, ibhām, its meaning elusive, calls out for such a translation, one that is quite deliberately not literal, a style he used on elliptical poets such as Stephane Mallarme.

Queer translation. Here’s Miraji on translating Francois Villon:

“I have culled only a few poems ad in them, even as I hold onto the soul o their words, the heart of what they say, I have kept Hindustani idioms and its expansiveness in mind, so that the pleasures that French and English bring their readers, can also be given to readers in Urdu.”

Miraji used the word mubham as a concept-metaphor to speak about the poems that he wrote as well as those by other poets. Mubham suggests the paradox of straightforward words whose meaning, like a Chipkalī, plays hide and seek with the reader. In this difference resides queerness, the quality that usually eludes us.

The poem begins with zabân, tongue but also voice, lyrical voice,absently tentative, flicking out like a gecko’s, to taste the essence of a flower, sample the sensations that make words come to life and bloom into lyric. The sinews in these opening phrases lie in ‘Mānind’ and ‘goyā’ — ‘like’ and ‘as though’. Neither settles easily: a bee’s dream, Its tantalising fragrance fading away, desiccated petals, the only tools a poet possesses to animate his corpse. The poet might be Nirala or Mahadevi; both pluck flowers from Braj, bloom them, dry them out.

The poet who skirts the edges of domesticity, a sojourner in a world passed along between bed and pyre but never entering a home; insights from the ashes of melancholia, living between occasions;ephemeral responses, falling and picking oneself up again, smile, someone who calls out, a person who may or may not come.

nagrī nagrī phirā musāfir ghar kā rastā bhūl gayā

kyā hai terā kyā hai merā apnā parāyā bhūl gayā

{Ghazal by Miraji)

This repertoire of ephemera appears again in other nazms such as ‘Jātrī ’ or ‘Samundar kā Bulāvā’ where Miraji dissects the lineaments of poetry attuned to mysticism, taps into the reveries and hallucinations, the detritus from the obliteration of poetic possibility after 1857. A mash-up that pulls and tugs, stretches and strains and petitions for a helpless, brutal attentiveness from a reader: the ambiguously political labour of modernism. Demands that the reader look again and again, pass from hand to hand what the poet says in many places, on the doors, running along the walls, filling the rooftops of their work. A reader has to get up,and fall again, pull himself up and ask: for whom did the lyric bloom?

In a chart which Akhtar ul Iman found in Miraji’s papers and gave me,Miraji uses mubham for himself, as a holding place where his own poems might mislay their transparency, misplace their faith in biographical, political, social, biological realisms and their crust soften up. Perhaps this is where — in mubham, in the ellipsis between mubham and realisms, in the ellipsis between genres of realism —Miraji finds the possibilities for his own khayālāt or might find khayālāt for himself. khayāl as soma — to arraign modernism as a queer practice.

Oyster pearls lace the water’s hem like fluted shadows.

Suddenly clouds gather in folds,

The sun briefly curtained

Boats secluded without a trace

And lingering along the water’s curve, oysters cupped open nakedly.

This allure of essence, offered up in ‘Jūhū ke kināre,’ “cupped open nakedly,” manifests the act of reading. Many readers enticed by the palpably erotic, find themselves “lingering” on the frisson in the flesh of the words, find themselves trying to draw out, like poison or like nectar,the real “real” kernel of Miraji’s phrasing. So that reading occurs, as in ‘Devadāsī aur Pujārī,’ through seduction,where seduction is the modulation through which a reader comes to an understanding about reading as such. Consuming the oyster flesh of this poem, erotica, erotics, eroticness, sex if you will — jinsiyaat—becomes the fetish through which such readers assign poems their value, through which such readers sieve their own desire.

Michel Foucault in‘The Care of the Self’—the first volume of the History of Sexuality —explores this allure of sexuality as the secret we endlessly track down. And certainly, Miraji’s invocations of sexualities, which were held taut between his own time and multiple pasts, drew me to the temptations of seduction, the lure of the secret.

Miraji’s poems live, like all good lyric does, not because of versification,not because one easily recognises their mauzu, their supposed theme; they live because the lingering rhythms of the poems’ lines build, twist and flow away from easy access to their meaning. The pearl in them lies supine in the place where reading itself turns queer: into a strange, ajeeb, paagal-saa, elliptical supplement, into a not quite complete and queer longing.

Strange Familiars

I took my tranquility on a walk

and chose my roads by their angled slant.

What I glimpsed I sighted from a tower’s height

The city’s glory seen so, from here

to those places of rest, what do I imagine

hold those gestures of hell for me: jails, whorehouses, hospital.Those places of rest bloom like the flowers of evil.

You know well, Satan, the cause of my discomfort.

You know well, this knowing: that I could not come here.

Eyes found on the road, alchemize

tears into flowers.I, the old and worn heart, a hedonist

and there, my faith tested on arrival,

Far away, I thirsted, my heart’s vagrancy

whose hellish beauty brings me to my youth.My heart clings to you,

your familiarity. Oh dishonored city

dream that sleep, heavy with wet shadows.

On your expanse bares the day’s first light, a wave gathering.

Your body, clothed with the plain dress of night’s colorprey and death-dealer, hunting the pleasures of their own being

the blind never come, to the humility of their degraded familiars.**********

Notes by the author

Introduction

Many lineages and forebears have been suggested for Urdu modernism or jadīdīyāt. One such finds its inception in the poet Altaf Husain Hali and his turn to lyrical naturalism. See Ahmed (2008) for another assortment of engagements that fall under the auspices of modernism, Ahmed’s lineage building exercises focus on transformations sited primarily in the formal features of lyric. Most conventional histories of 20th century Urdu poetry are routed through three well known lyricists—Miraji, N.M. Rashid and Faiz Ahmed Faiz

Part I & II --The translations of poems by Sappho from Miraji’s Urdu translations by me. The original is: Mīrājī. “Saifo.” Mashriq o Maghrib ke Naghmen. Lāhore: Akādamī Panjāb, 1958, 321-356. |

--My translation of Miraji's translations into Urdu of “Ave Atque Vale” by Swinburne and “Strange Familiars” by Baudelaire (which Miraji probably saw in its English incarnation). Original in: "caarls baudela'ir"in Mashriq o Maghib ke naghme, 161-189, 184. Swinburne’s poem p 182. “Strange Familiars” is one of the few poems that Miraji translates without offering a commentary or supplementary reading. “Being” can also be translated as form or forms.

Geeta Patel is Professor at University of Virginia’s Department of Middle Eastern &South Asian Language and Cultures. Her work spans gender, colonial history, poetry, feminism. She holds three degrees in science and straddles an interdisciplinary world of science, finance, cinema and media as well. Some of her notable publications include Lyrical Movements, Historical Hauntings on the Urdu poet Miraji and Risky Bodies and Techno-Intimacy.

Leave a Reply