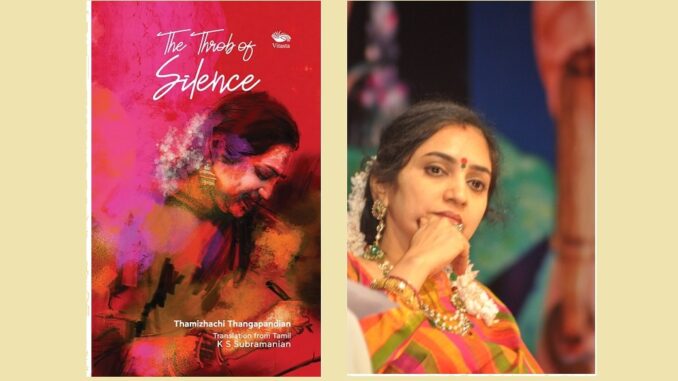

The Throb of Silence, by Thamizhachi Thangapandian. Translator Dr K.S. Subramanian Vitasta Publishing Pvt Ltd. 2023(Hard bound), pp158, Rs.425.

A.J.Thomas

Dr.T.Sumathy, The Member of Parliament from Chennai South, better known to the literati as the influential Tamil poet and fiction writer Thamizhachi Thangapandian, has come out with an emphatic voice in women’s writing in Tamil, lately through her poetry collection in English translation, titled The Throb of Silence by K.S.Subrahmanian. The book was released in a glittering function held in Constitution Club, New Delhi, on 28 March 2023, where eminent personalities like Ms.Supriya Sule, MP, Dr.Sonal Mansingh MP, several other MPs, spoke. Professor H S Shivaprakash, celebrated Kannada poet and playwright, Dr.Lakshmi Kannan, well-known poet and fiction-writer writing in English and Tamil, and myself examined in detail the uniqueness of Thamizhachi’s poetic voice.

Earlier, in 2022, she had showcased her brilliant offering in Tamil fiction for the non-Tamil-reading public, through Birthing Hut and Other Stories, translated by V Bharathi Harishankar. Her first poetry collection in English translation, titled Internal Colloquies done by the respected professor of English, Dr.C.T.Indra, published by Rubric Books, in 2019, had drawn my attention for their freshness and direct appeal, as I had published a review of it in Indian Literature soon after.

The Throb of Silence carries two Prefaces—one by acclaimed translator Sri N Kalyan Raman and the other by Professor H S Shivaprakash. These succinctly place Thamizhachi in a unique position in contemporary Tamil poetry, with her five collections that have garnered wide critical acclaim.

I quote from N Kalyan Raman’s Preface: “In an age where tempers run high and abstraction holds sway over our consciousness, Thamizhachi’s perspective is poised and rooted, paying close attention not only to the natural world but also to the tremors of the passing moment in herself and others. Her voice is gentle and reflective, steeped in irony and wonder at the ways of the world, and sensitive to her own fears and yearnings.”

N Kalyan Raman goes on quoting her poem which he translated titled “My Poetry,” to illustrate this point, which I quote here:

A time past

Of flawless grammar

And flowing rhythm

The present

Steeped in

Semiotic strategies

Modern and postmodern fiction

Deconstruction and sundry ‘isms’

In the melee of this festival

My poetry has

Happily lost its way

Like an unclothed, guileless child.

This poem serves as a manifesto for Thamizhachi’s poetry, as both the Prefaces point out.

Professor Shivaprakash’s Preface explores Thamizhachi’s poetry in a detailed, voyage of discovery-like narration. The highlighted centre-point of his argument, which I quote, “In her prose and poetry, Thamizhachi is struggling to keep alive and celebrate, pristine feminine power which has been time and again trampled(sic) by successive phases of urbanisation and modernisation presided over by patriarchy.”

In an emphatic attempt to situate Thamizhachi’s poetry, Shivaprakash describes the greatest poetry as emerging in moments of violent crisis and transition and pinpoints the advent of modern urbanisation as a historical paradigm-shift of epochal proportions, over the last couple of centuries, proving to be literally crushing in its pervasive, disruptive impact globally. The modernist process of dehumanisation resulting from it has a universal pattern, he says, although its regional manifestations vary from place to place, language to language.

Coming back to his main argument, Shivaprakash identifies the supreme feminine power in Thamizhachi’s poetry, as “Vanappechi”. In the millennia-old women poets’ tradition in Tamil, embodied in the poetry of Avvayar of the Sangam Age, the 5th century AD Karaikkal Ammayar, the only woman Nayanaar of the Tamil Shaivite tradition, or Andaal, the only female Alwar of Vaishnavite tradition, of the 7th century AD, we see the emergence of ‘mainstream’ spirituality that developed over time, under the influence of various Aryanised deities. However, Thamizhachi’s Vanappechi is different. The poet declares, and I quote, “Vanappechi is my Alter Ego. She is an indigenous village deity whose name literally means, “a mad, fierce woman who resides in the forest.” A woman without any shackles, representing the rugged and raw sensibility of a southern regional rural woman!

She never wants any shelter above her head—she is an epitome of free spirit!

She dwells in the forest and resonates the Matriarchal Supremacy of Womanhood.

She is people’s guardian deity, synonymous with kaaval Kaappathu in Tamil.

“Through her, I express the untold stories of my women folk, the taboos they want to undo, demystifying those cultural burdens which they are forced to carry on for centuries! She is the voice of my soul—my partner in crime—my chum—my backup as a pillar of strength!

She is Me!” Exclaims Thamizhachi.

As Shivaprakash observes, Thamizhachi’s poems address the present, through this primeval spirit, though her kind of world is in definite decline; however, she enters and interacts with the modern world, because she is throbbing in the poet’s being. Vanappechi pervades many more of her poems.

Thamizhachi’s view of the harmony found in nature as part of her own internal ecosystem as well as the society’s collective heritage, ensures that she does not alienate herself to gain perspective like the modernists do, and unapologetically remains one with it. This results in her passionately being with the present, with the quotidian.

Several of her poems are topographical, to the point of reminding one of ancient Tamil poetics centred around the concept of the five tinais or ‘terrains’ forming the theme, or locale of the poems.

In some of these poems, the conflict between the collective memory of the village community down the centuries, and the modernity thrust upon it by abrupt and fast urbanisation, happening under one’s very own gaze, is dramatized through juxtaposition.

In “Passing On,” the poet describes the act of transferring different aspects or elements of oneself, at a point of transition or transformation, and opens with the pithy lines,

“It takes real hard work

Not to leave behind

Anything worth remembering.”

Indicative of moving from one station to another or making a clean break, transferring oneself from a location, with its memories and all: However, the poem ends with the cryptic lines:

‘While passing on even one word

From ancestors

How can we help

Passing on to successors

Something worth treasuring?’

Herein lies the crux of the cultural continuum Thamizhachi proposes to pass on to posterity, from the millennia old cultural ethos she has inherited. This preoccupation, or cultural anxiety, is what defines a very different kind of poet in our times of instant happenings.

The poem titled, “Inside, Outside,” which is autobiographical and is about her native village, and about her dear departed father, evokes the oneness with nature she has achieved, melding her memories, the moods of nature and the topography around.

“Neem Flower in Summer,” is of a similar mood and setting. After describing the village in the grip of a horrid summer, drying up its streams and tanks to a trickle, and parching even its very soil, the speaking subject concludes:

“Your longing memory

lingering like a peacock feather

buried in the dried up Kanmaai

bed….As the memory coalesced into a dark

cloud

a cruel wind tears it apart

as if only tears are the proper rain

for this wretched black soil.”

“The Sixth Sense” is an intense poem, replete with abrupt and rough-edged images, working towards the resolution of an emotional engagement, on the face of it. Emotional conflict and confrontation eliciting this:

“Your love escapes with struggle

–a charred stench

My nose smells

As the stench of undigested breastmilk,”Reaches a denouement ending the poem with these lines:

“When narrating with dismay

Like a beggar woman ruthlessly driven

Away

What else do I have

Except my black-hued tears

And the love lingering

Like the sixth sense!”

Here’s another poem, which is a sibling to this one. “Confrontation,” opens with these tell-tale lines,

“When you decide

What words I should choose

The silence I keep is strong and

Eloquent,”

And goes on with describing strikingly contrasting responses, to the perceived affronts of the ‘other’.

The poem, “To That Vulture,” deals with the unrelenting attack of Time, on all things transient. And ends with:

“As it approaches you menacingly

Do reward it suitably

With no misplaced solicitude

A smile that shrouds the pain

And a pebble kissed into shape

By ageless swirl of water.”

Inhuman atrocities during war are a perennial theme for sensitive poets. The poet’s consciousness crumbling at the memory of several children killed in a Sri Lankan army attack on an orphanage-like shelter at a place called Chencholai, finds a searing expression in an eponymous poem. Another one of its kind is “Al Janabi’s Sixth Finger” in which is narrated American soldiers in Iraq gangraping and killing a 14-year-old.

Dwelling on themes such as these, the 62 poems in this collection speak to the reader in an intimate language of heightened sensibility only poetic minds can share.

I can only thank the translator for bringing out these poignant, earthy poems in English, for the wider world, projecting Thamizhachi’s enduring love of words and verse.

*****

Thamizhachi Thangapandian Dr T Sumathy aka Thamizhachi Thangapandian is a Tamil writer, English Professor and a Member of Parliament. She has nineteen publications including collections of poetry, essays and interviews to her credit.

Dr KS Subramanian A renowned name in translations, the late Dr KS Subramanian has translated over 40 Tamil literary works into English. These include novels, novellas, collections of short stories and anthologies of poetry. He has also translated a large number of collected essays and biographical and autobiographical works. His translations have been published by the Sahitya Akademi, Macmillan, Katha, East-West Books, Westland, Tamil University, International Institute of Tamil Studies, Central Institute of Indian Languages and others. He has received several awards in the field of literary translation.

A.J. Thomas is an Advisor to The Beacon. He is a poet, translator and was till recently editor with Indian Literature journal of Sahitya Akademi. A.J. Thomas in The Beacon

Leave a Reply