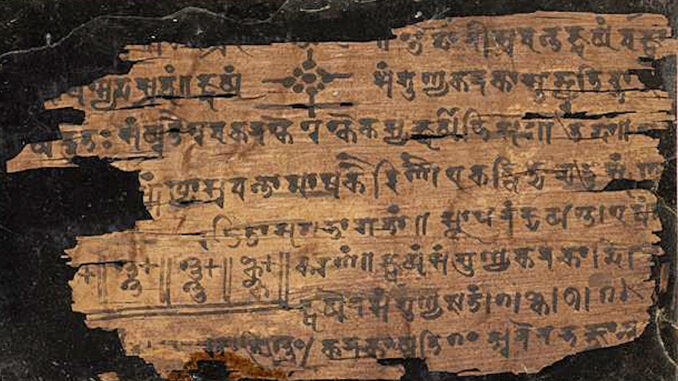

Representative image

Prologue: Why Bother?

One of the momentous aspects of the British colonial rule was the introduction of what Max Weber called “calculable law” in the latter part of the 18th century. Warren Hastings made strenuous efforts to avert the imposition of British law and institutions in India. Contrary to the view shared by many at that time that India never had written laws, Hastings argued that India’s laws are available in the books and texts belonging to remote antiquity which are known to the Brahmans, as professors of law. The task then was to make these so-called texts of law serviceable for the sitting judges in the civil courts who hear suits concerning property, inheritance, marriage and caste, debts contracts and so forth. Thus began the project of creating systematic laws for India on the basis of Hindu and Muslim texts, qualified as legal, which went on for another hundred years. While the germ of the idea came through Hastings, it was successively put into practice by the British civil servants and jurists at that time, like mainly N. B. Halhed, William Jones and Henry T. Colebrook among others. Halhed published A Code of Gentoo Laws;or, Ordinations of the Pundits in 1776, the first ever to come out, which was indeed a translation of a work initially done in Persian by a Bengali Muslim who in turn based his work on the relevant Sanskrit sources with the help of pandits who would advise him in Bengali. One cannot miss the challenges of translation across multiple languages in this context, from Sanskrit and Bengali to Persian and English.

William Jones, the Oxford trained classicist who formally studied Persian and Arabic, came to India as a judge of the Calcutta supreme court in 1783. He subsequently learnt Sanskrit and embarked on the task of producing a proper compendium of laws which supersedes what he perceived as the defects of Halhed’s work. According to Jones, the chief difficulty in India was that laws and codes were barely ever preserved in their original and pristine form. They had become corrupted by accretions, interpretations and commentaries over a long period of time. Any adjudicator for these laws therefore had to depend on a contemporary lawyer or pandit to identify the right interpretation of any particular law which is true to its original and pure form. What one could hope for in such a situation is anything but a “calculable law” in Weber’s sense which ought to allow “predictable outcomes” where the scope for arbitrary rules and laws is minimal. Jones hence wanted a “complete digest of Hindu and Musalman Laws, on the great subjects of Contracts and Inheritances.” With a help of a couple of pandits and maulvis, after securing the approval from Cornwallis, Jones undertook the compilation of Sanskrit and Arabic texts which eventually bore fruit after his death in the hands of H. T. Colebrooke as The Digest of Hindu Law on Contracts and Successions in Calcutta in 1798. The Digest is essentially a translation of the compilation of original sources with Jones’ commentary.

One can hardly exaggerate the influence Jones had, who was a trained as a jurist in English common law, on subsequent legal thinking in India. English common law was and is in practice always seen as a case law—a law based on finding precedents—although it did partake in the tradition of natural law and incorporated its key ideas of justice and equity from the natural law tradition. There was a palpable tension in Jones’ effort to bring his legal training to bear upon the project of drawing up laws for Indians.

Contrary to how law worked in England, which was seen as responsive to historical change because the manners and habits of people change over time, Jones believed that in India the laws always have fixed usages from ancient times and will have to be applied on people whose customs and habits do of course invariably change over time. The law will however remain unchanged, as Jones understood, with the implication that it is timeless. When a given law is interpreted variably by different pandits, Jones thought, the difference arises because of other motives or even ignorance. Besides, Jones made a separation between ethical and religious matters and the issues of legal principle. Therefore, he excised from his compilation the portions related to ritual, incantation, and philosophy, and only retained those rules which he thought corresponded with the British understanding of matters pertaining to contracts and succession. This sort of a separation bespeaks, apart from a decontextualized approach to texts, of an uncircumspect imposition of one’s own cultural framework on an altogether different culture. This is a case of hermeneutic violence. As it happens, none of Jones’ mostly fanciful ideas about Indian texts quite survive subsequent critical opinion. His successor, H. T. Colebrooke, did not have Jones’ training in law but had a great command on Sanskrit and a firmer grasp on the shastra texts and the commentaries devoted to them. He brought in a much wider gamut of texts to bear upon the project of the Digest. According to him, the separation between books of law, called sanhitas, and the commentaries on them is an artificial one; together, they form the core body of legal texts. While the sanhitas are essentially composed by holy personages as sets of prescriptions, the commentaries are the work of subsequent scholars whose aim was to elaborate and clarify the contexts and the underlying principles of these prescriptions. Both the sanhita texts and the commentaries are always held in high respect by the adhering communities, indicating their sacrosanct nature, and conflict naturally is frequent and inevitable.

Colebrooke’s approach differs from Jones’ principally in terms of his recognition that conflicts between texts is quite natural, and that these need to be methodically resolved. There was of course Mimamsa—a discipline devoted to setting up rules of interpretation of words, phrases and sentences along with reasoning strategies—meant to reconcile conflicting texts which rival each other in authority and legitimacy. Colebrooke attributed differences between texts to historical and cultural variation of the people in India. While this is true enough, he also made several assumptions to be able to organize these differences to conform to what he called the numerous “schools” of Hindu law. As Ludo Rocher argued, this idea of “school” is alien to the Dharma Shastra texts and their commentaries, and is closer in spirit and content to the English conception of the “law of the land” which reflects in the customs of various parts of the country. The commentators on sanhitas were not like lawyers, as Colebrooke thought, who employed mimamsa to extract the original and the right picture of the law that is under consideration. In fact, the commentator’s job is to elicit and evince the discursive character of the text and give a direction for some sort of a local application so that the “law” comes to one’s aid in matters needing adjudication. The interesting thing about these texts is that they embody a full-fledged situation of discourse and its enactment in language.

In spite of William Jones’s heroic attempt to provide a law code for India, on the basis solely of Indian texts, albeit mediated by the British judges (assisted by pandits and maulvis), what eventually triumphed in practice was a peculiar variant of English case law. Most of the justifications and arguments given by Jones and Colebrooke have vanished from the scene in due course, and there is scarcely anything resembling their intent and effort in the current thinking about law.

It is worth asking what led to the derailment of Jones’ project. One way to answer this question is to say that Jones and company had no inkling whatsoever that texts are complex entities, and that they always come into being only in a discursive situation. Commentaries, aside from the usual tasks they fulfill of elaboration and clarification, also tend to reconstruct, at least partially, the discourse of a given text. They are in main prepared to preserve and also further the community specific discursive traditions of reading and interpretation. We should note that surrounding the so-called legal texts there have always been live traditions of adherence, exegesis and interpretation. Jones’ project of formulating a law code, not to speak of his ambition to found a code similar to the Roman code of Justinian, conceived and executed under the shadow of the state, forced complex historical enactments of reading texts to conform to the narrow jurisprudential expediencies of running the state.

If something as mundane as reading texts can have such momentous consequences, we better know what texts are and how they work. India for millennia has been flooded with texts, of all kinds, metaphysical, literary, scientific, technical, spiritual, incantatory, political, military and many others cutting across all genres. In the face such immense wealth of texts and textuality we need to know what makes something a text even before we take it for granted as a text.

**

Is there a right way to read texts?

T

here cannot be an answer to this question in the affirmative. One can say that this is the fruit of a hundred or so years of research and thinking on the question of how to read and interpret texts. Schleiermacher, the 19th century German philosopher, who did most to establish the discipline of hermeneutics–the science devoted to the study of interpretation, believed that it is always possible to understand an author better than how he understood himself. From Schleiermacher’s time onwards we have come a long way although there is still much that one can find interesting and insightful in his work. In fact, it was he who gave the famous idea of the hermeneutic circle–that there is always a dynamic interplay between parts and the whole while reading and understanding any text. While Schleiermacher believed that it is possible to reconstruct the correct meaning of any text, now the consensus is that such a reconstruction is impossible. Over the last hundred years both the ideas of the text and the interpretation have undergone heady developments. Text is no longer a thing of the past and tradition, like the Bible for instance, nor is interpretation an act of getting to the kernel of a given text’s message.

Now anything that is capable of communicating a message is taken to be a text. So, from traffic signals to billboards to boarding passes to stock market scrips can all be construed as texts. One can always read off meanings from them. Their meaningfulness is the sole criterion for their textuality. While this universalizing tendency about the texts is widely welcomed, perhaps for right reasons, one cannot help thinking that this sort of approach frequently relies on empowering the reader as the sovereign source of meaning. I won’t dispute that this approach has its uses, particularly in such cases, ethnographic instances for example, where the reader has to see, demarcate, and flesh out a text on his/her own. Of course, nothing about this activity reflects the wilfulness of the reader. Here culture itself is construed as text, as a semiotic system, where the surface belies what lies underneath, hidden and undisclosed. The interpreter’s role explicitly is to uncover the outer layers so that the deeper layers become visible, i.e. to render the implicit explicit. Clifford Geertz’s justly famous ethnographic account of the Balinese cockfight is an exemplary instance of this kind of an approach. Scores of anthropologists over the last so many generations have been conducting fruitful interpretive practice of this sort.

The problem however with this approach is that it obscures the character of the text, particularly because it rather sets few and minimal conditions for a text to be called a text. This in a way amounts to setting a minimal baseline so that it becomes possible to lay out a standard for the rather bewildering and extant variety of texts all over. Texts are not verbal, visual or phonic alone; they also have spatial and temporal characteristics. Indeed, certain texts acquire their textual character only as performances, which means that their textuality is dependent on the contingent factors at work in each instance of performance. In fact, what makes the proposition that texts should have one single meaning or that there must be one correct way of reading any given text implausible is the sheer multidimensional complexity of texts. By this I mean that texts have numerous, dimensions: structural, semiotic, semantic, phonological, historical, political, discursive and so on. One cannot reduce this complexity by empowering the reader and shifting the burden of unraveling the texts from their sheer status as texts per se to their interpretability. Texts are like things in the world notwithstanding the fact that they are the products of human consciousness. Jacques Derrida famously said that there is nothing outside the text, implying that all forms of signification, classification, structuration, demarcation, separation etc make sense only if they happen as part of the general textuality shared by all that construed as reality, including ourselves, and consequently how we get to understand things as they emerge being part of the general text. What is the “general text” in the global sense has its local manifestations as the texts we encounter on an everyday basis.

In what follows I will make an attempt to show what makes texts complex, not just their genesis but also their reception. My intent is ecumenical rather than sectarian, and synoptic rather than piecemeal. The terrain of debate is indeed fraught with many fractious issues. There are several competing positions about texts, and each one has its own strengths and biases. I will synthesize a few key insights about textuality, drawing on the debates that have happened in the last six decades or so. Although the article’s general aim is to clarify and elaborate, at the theoretical level, on how texts mean and function in discourse in general, it particularly seeks to highlight a few problems that arise in the course of interpreting them. Firstly, to assume that texts preexist interpretation is a naive and positivist assumption. Prior to interpretation, what we subsequently take for texts are a mass of pure physical marks, be they of ink, or paint or any other substance. Secondly, texts never come preloaded with a fixed set of meanings or facts. Meaning is something that gets constructed in the act of interpretation; and a fact becomes available only through redescription. Thirdly, interpretation is always regulated by discourse. This implies that interpretation is a constrained affair. The constraints are not merely empirical but discursive. I owe this particular insight to Paul RIcoeur. While I will not frequently mention the names of Gadamer, Barthes, Ricoeur, Derrida, Kermode et al much of the subsequent discussion owes to the ideas developed by these thinkers. For I wish to refocus our attention on hermeneutical reflection which has lately fallen off from both critical and public discourses. The disappearance of an interpretive stance, and the corresponding belief that interpretation plays an indispensable role in any act of cognition, symptomatically speaking, would make way for dogmatism, recession of dialogic spirit and the triumph of monologism, both in academia and in public culture.

What is a text?

This is not the right question to ask, for it demands that we conclusively define what a text is. One could indeed argue that all definitions run into difficulties. If we say that a text is a piece of writing, then it would exclude a piece of music from its scope. If any symbol system is a text, then what about natural landscapes? The landscape after all means much to the discerning viewer. Instead of finding a definition capacious enough to include all sorts of texts, what I would suggest is, following the lead of Paul Ricoeur, that the text is essentially a piece of discourse.

The advantage of invoking discourse is that it defies all definitions. Discourse is not a thing; it is instead the condition or the context which enables the production of intelligible behaviour. The tangible aspects of the discourse are people, as speakers, and things, and bits of sound we call language; and the intangible aspects are thoughts, feelings, fancies and moods. Discourse is the precondition for thought–propositional or not–to get into a medium. For instance, language needs discourse for it to come into being. No language, as speech or writing, gets produced in the absence of discourse. If a given text is a piece of language, then discourse must be at work for it to have been produced. Language needs speakers who share relations of mutuality and/or reciprocity and are talking about something or other, which they may have in their vicinity or not. In language, the sentence is the primary unit of discourse, which decides the kind of use to which a particular piece of language is to be put to. While language exists as a system only virtually, we owe this insight to Saussure, it is the discourse that allows language to be actualized into usage. Once actualized, language gets ensconced in a context and acquires a temporal character. The usage implies speakers and hearers/writers and readers, and a format for dialogic exchange. Discourse never lasts beyond a time frame within which it unfolds. Discourse then is like a happening which begins at a certain point and ends at a later point. The duration between these two points is equivalent to the very incidence of discourse in real time. Any piece of language should be construed as an integral part of the relevant discourse for it to make sense in the first place. Even an instruction in a public place must be seen as an utterance from an impersonal subject, and meant for the myriad anonymous readers or auditors.

It is now clear that texts presuppose the workings of discourse; and discourse primarily occurs as an event that unfolds in time. When an event is spoken or written about, discourse acquires the character of meaning. Hence, event and meaning are the two sides of the same thing called discourse. Discourse refers on the one hand to the speakers, in a self-referential manner, i.e. to those who take part in the event as speakers or actors, and to the world it refers to or accommodates on the other. So, texts always by necessity contain discourse, and are formed by discourse. Texts do not become intelligible to us if they are not seen as constituted by discourse. Now, the task of interpreting will necessarily assume the role of discerning and unpacking discourse in the texts, and its multiple levels, which are always given in and through the enabling discursive structures of an intersubjective situation. There are utterers and auditors within the text, and likewise linguistic forms and patterns, and there are authors outside the text who also strangely belong to the wider horizons of the text itself. One could suggest that certain structures lie beyond discourse, as structuralists do suggest, which may or may not play a role in interpretation. Such structures indeed perform an explanatory role, as illustrated in Claude Levi Strauss’ exemplary work on the myths, and could inform interpretation in an enlarged sense, but the meaningfulness of the texts need not depend on them. One could quite well argue that interpretation follows explanation. Meaning is the only mode of access through which interpreters seek their entry into the world of texts. As stated earlier, meaning is one of the forms assumed by discourse. As it happens, all explanation happens from outside the text.

Taking stock, texts emerge at the intersection of speakers, auditors, language and the world. Defined thus, anything that satisfies this condition must be a text. For any given piece of linguistic text, fictional or otherwise, of the present or the past, it is possible to reconstruct the discursive context within which it makes sense. So far so good. Now, if a text were to refer to an imaginary world, as all works of fiction do, then how do we account for the world then? The problem here is that such a world does not exist in space and time. How do texts address the problem of the non-existent? The happy news is that it is not a problem for texts. It would instead be a problem for the readers/interpreters. It is the interpreter who has to decipher and decide whether he/she is engaging with the representations of the real or the fictional world. Whatever his or her decision, it poses no real challenge to how one may cognize the world a text talks about. It may have other consequences. An interpreter may construe the fictional world as a metaphor for the real; or one may find the accents of the fictional in the real. One may, mistakenly or even wantedly, swap categories and render real what in fact is fictional or vice versa. At any rate, even the fictional world, unless done with an intent, imitates the registers of the actual world. The characters in a novel mostly eat rice or bread, and not wooden or steel plates.

Painted Words. The Mewari Miniatures of Allah Baksh in The Gita: A Review by Bharani Kollipara

From Work to Text

The word “text” comes from the Latin textus, which means “style or texture of a work,”. It literally means a “thing woven,” from the past participle stem of texere– “to weave, to join, fit together, braid, interweave, construct, fabricate, build.” The underlying metaphor for text is weaving, implying that there is always an element of design, careful arrangement and artificiality to making texts. The concept of text was floated for the first time by the French structuralist critics mainly to discover an alternative to the more traditional category of “work”, usually applied to literary works. The idea of “work” always valorised the author whose consciousness and intentionality were seen as important to account for the features and the specific value of a given work. The idea of text emerged as an alternative to this style of thinking, with the aim of viewing the text as a medium by itself, as a depersonalized artifact which can be meaningful on its own terms. The polemic of Barthes and Foucault on the death of the author must be seen in the context of this shift from the work to the text. The text is seen as a product of the social institution of writing-ecriture. The texts have their own structure and semiological systems, independently of how the authors conceive and execute their texts as works. All texts have patterns of internal organization which are shared by other social and cultural systems too. Besides, since the authors take part in the social system as signs themselves, their writings too bear and reflect the tacitly absorbed cultural and structural forms of organization. The notion of text gained prominence in the study of literature only as the value and standing of the author receded. One cannot fail to notice an underlying hypocrisy in this textual revolution: the rise of the text as the preeminent literary category by no means has put the authors at a disadvantage in reaping from their copyrights!

The structuralist and the semiological concept of the text made it possible to ask new questions about the role of language and subjectivity in texts. While treating what was formerly “work” as a “text” now certainly amplified the prospects of analysis, interpretation and exegesis, and expanded the possibility of what texts could reveal, but the text still remained subservient to the aims of analysis. The aim has always been to fit a text to what one wants to say on its behalf. Interpretation often is expected to yield to the vagaries of evidence and analysis. However, texts surpass analysis in important ways. This is Derrida’s central insight, namely that texts range beyond our ability to analyse them, as things bearing the discourse with a direct appeal to our ability to interpret them. Once “work” ceases to be an intelligible category, it becomes possible to see text in the light of an expansive remit of characteristics. Here is a list of them, not an exhaustive one though:

- One very important feature of texts is that they betray a communicative intent, so argues Manfred Frank, if not a communicative function all the time. There are texts belonging to deep antiquity which are still not deciphered. Although we know that they were clearly written with a communicative intent, we do not know what communicative function they served.

- Texts defy death. Inscription is the way to immortality. Once written down, a text attains permanence even after the ephemeral material on which it is imprinted is destroyed or lost. Texts, as bearers of propositional meaning and beyond, acquire a kind of virtual existence.

- Texts are both touched and untouched by history. They bear the traces and evidences of the historical time in which they are born; at the same time, their meaningfulness is not exhausted by history.

- One way to look at texts is that they always have representational content, whether referential or not.

- Texts are never worldless. They always refer to worlds, imaginary and real.

- Texts, even single word lexical units, are composed of parts and wholes. The parts may be its words and sentences, or its abstract units of meaning, and the whole whatever renders them together. Texts become meaningful as a result of the interplay between between their parts and wholes. This was the Schliermacher’s point about the hermeneutic circle.

- Texts, whatever their antiquity, never lose their ability to address even a far distant reader.

- Texts tend to be a diverse lot without losing their ability to address a single theme or story. How else do we explain the sheer fact that there are so many versions of stories, say, of Ramayana or Mahabharata?

- Texts span several genres, from literature to history to science. Texts are beyond truth,i.e. they cannot be a source of truth qua texts alone. Texts cannot attest to the truth or validity of whatever their contents refer to. They can only be validated by comparing with something other than themselves which may either be texts or not.

- Texts by themselves do not depend for their survival on the sanction or the authentication granted by their progenitors. They of course entirely depend on their readers for dispersal and dissemination.

- Texts allow themselves to be frequently misread. Misreading springs from the fact that readers can never be disinterested readers. Only a machine can read text without any traces of interest. So, machines cannot misread. Misreading is not the same as misrepresentation, which involves willful distortion often with some vile motive.

The above list is not meant to be exhaustive, but it captures the complexity that surrounds any given text.

Interpreting Texts

In the discussion so far, apart from the several subsidiary points, we have established two broad claims which are related to each other: 1) all texts presuppose the workings of discourse; and 2) texts display multifold complexity. Both these claims have direct implications for the interpretation of texts.

Any text, literary or otherwise, raises questions for interpretation. This is because, in Ricoeur’s words, the aim of interpretation generally is “to struggle against cultural distance and historical alienation.” Texts embody, as suggested in the previous section, both the problems of distance and alienation. Texts by themselves mean nothing. They need to be interpreted for both meaning and understanding. Let us consider the case of a text of distant antiquity which is available only as a copy of a manuscript. By virtue of its antiquity, it is distant from us, both culturally and historically. It may be a text of some obscure science or some esoteric learning. It may even be granted great authority and sacral status on account of some extraneous factors. However, unless a text is taken in and accepted by a community as its own, no text would survive as a document of commanding authority. When a text finds its home in the continuing tradition of a community, it survives only because it is constantly interpreted and reinterpreted. In the case of the ancient manuscript one can only look at it forensically, and make an attempt to retrieve its meaning with the available tools while making no or minimal presuppositions. Hence, philology often gets fraught with serious compromises. An important measure of a text’s distance is the fact of its disembeddedness–not being part of any living community. A disembedded text is the most difficult one to interpret because all the pathways of interpretation have either extinguished or sunk so deep into our habits that they remain as unidentifiable sediments. Until one starts to interpret, sometimes by way of getting to the roots of our old habits, the text is no more than marks and patterns on a parchment or palm leaf.

Unless treated as a subject matter of abstruse theoretical debates, interpretation is unfortunately either relegated to the more esoteric matters such as interpreting symbols, mysteries, obscure metaphors, or is subsumed under the more mundane task of textual interpretation, possibly under the aegis of theory or a framework. Here interpretation’s role naturally gets minimized and reduced. The theory generally anticipates meaning. What becomes obscure here is the fact that interpretation has a practical dimension in that it allows a reader to see how a given text makes sense to him as a person who comes with a specific set of expectations, endowment and outlook. Sometimes texts become entangled in ritual. The Srauta texts of the Vedas offer a good example. Text and ritual action go together to such an extent that either one would lose meaning in the absence of the other. An utterance would make sense only if accompanied by an appropriate gesture or action. Similarly, the case of uttering sacred mantras, which indeed combines mental effort of a certain order and kind and bodily action. In cases such as these interpretation becomes complex and intractable because bodies also acquire a share in how bits of language and the relevant material objects mean to an interpreter. Interpretation in this fundamental sense shares kinship with one’s core beliefs and convictions, possibly precedes even analysis, and could become coextensive with habitual perceptions and values. While analysis needs skill and craft, and is frequently technical, interpretation can be both spontaneous and studied.

Let me clarify how interpretation works with the help of Frank Kermode’s analysis of the parable of the Good Samaritan in his The Genesis of Secrecy. Kermode’s essential point is that interpretation is interminable and is often marked by cultural specificities. The parable is about a traveler who is robbed and assaulted, and who is left wounded in a ditch. Two passersby, a priest and a Levite, ignore him, but the third one–the good Samaritan–goes out of his way and helps the traveler–bandages his wounds, treats him with oil and wine, carries him to an inn, and even pays for his stay there. Samaritans were a hated ethnoreligious group in the ancient Judaic world. The parable seems to be a “simple exemplary tale” to illustrate who the true neighbour is in the Christian sense. What indeed strikes us as a natural interpretation, namely that the Samaritan had done only what one could do to help a fellow being in distress, is specific to us, to our culture and our modern ways of social life. Someone who belongs to an order of the Church reading this parable a thousand years ago would scarcely find our interpretation the most “natural”. The parable assumes great allegorical significance with specific meanings of each and every bit of the narrative detail presented, including oil and wine. What seems natural to someone after all is arbitrary and cultural. The question ”who the true neighbour is?” can’t be settled easily. The Greek word for “neighbour”, plesion, Kermode tells us, is related to the Hebrew word for “shepherd”; the word “Samaritan” comes from the same root as the word for shepherd. Thus, the good Samaritan would evince for the believers the coming of the Good Shepherd. One cannot put a stop to interpretation.

Interpretation, unlike analysis, directly addresses our demands of understanding. Even the first level of classification, say, to call the manuscript obscure, is also an act of interpretation. Some minimal understanding takes place at that level. While this point is widely canvased, and interpretations are often deployed taking into account various contextual factors, interpretation per se is taken to be something which has a high degree of variability in application and use. That is to say, there would be different styles of interpretation of any given text. While it is true that there are various forms and modes of interpretation, and what appear to be their examples, this does not however imply that interpretation is no more than establishing concordances and equivalences between two or more things with the aim of clarifying what is stated and expressed in a given text. This would be exegesis or commentary rather than interpretation. Exegesis can only follow interpretation, as a subspecies, in the form of a subsidiary mode of clarification. Interpretation is more than exegesis in that it has larger aims of bridging, as suggested earlier, distances of culture, history, and even mentalities if possible.

It appears that interpretation aims at a meaning which can be abstracted and stated in some transparent form of a proposition or thought. This proposition is assumed in turn to acquire a currency of its own as a stable self-enclosed unit of meaning. If this model of interpretation were true, then it could be called the positivist model. The very fact that interpretation is interminable attests to the falsity of this assumption. Besides, interpretation is always constrained by what the discourse makes available. Discourse includes, in a capacious sense, both the utterers and the auditors of a given speech or text. Whenever discourse is at work then meaning cannot be made available as a stable platonic entity, for meaning is perpetually subjected to the fluctuations and instabilities and contingencies of the discourse that is at work in any given text. Sometimes the availability of meaning could become inordinately difficult, not because we lack the necessary skill and expertise to unravel it, but because of the very unstable conditions which determine the emergence of meaning in discourse, then the task of interpretation will be as much difficult and demanding. This sort of a situation would apply to any instance of a text, be it a single verse kavya or an extant poem. By way interpretation, an interpreter only temporarily arrests the instability of discourse, and thereby produces palpable meaning. As it happens, historical writing often faces a compounded version of this sort of a difficulty particularly because reconstructing the discourse of past events is always prone to impending uncertainties due to insurmountable inadequacies of our knowledge of the past. Even so, avant garde modernist texts, like the Joycean ones, also pose similar challenges because the principle of their construction is often to reflect the instability of discourse.

We try to meet this difficulty with one of the most inanely used words, i.e. subjective. Interpretations which seem to have been motivated by arbitrary associations, sometimes they plainly lack good sense, are relegated to the sphere of the subjective. In other words, it amounts to a sanction of the claim that anything can mean anything else provided we apply an interpretive charity broad enough to cover the entire domain of meaning. To be fair and balanced, there is nothing like either a subjective or an objective interpretation. All interpretations are regulated by discourse which coordinates the play between the subjective and objective poles in any act of reading. Only a reading which glaringly trespasses the limits of discourse would appear outlandish and gratuitous. Of course, if discourse plays such an important function, one could well argue that interpretations reflect the ideologies which are at work in a given discourse. There can scarcely be a reading that exceeds the underpinnings of ideology. One cannot read a 19th century realist novel without getting drawn into its ideological system and the collateral assumptions about class, prejudice, education, gender etc. It should however be possible to rid or at least minimize the incursions of ideology into discourse, like for instance when interpreting the modernist texts, Mallarme for example. Mallarme wrote radical texts, and it becomes possible to radically read them. But it is a struggle nevertheless, I admit, with a limited promise of redemption from ideology.

I will close with a schematic picture of how discourse enables interpretation to take place. One could argue that there are broadly three levels of interpretation ranging over different degrees of complexity.

At the first level of interpretation, the attempt would be to identify and recognize the things of the first order. For example, the interpreter will identify the objects and persons and their relations depicted in the text. This is the first order of interpretation. It is first order in the sense that there is almost no more interpretation than barely fixing the people and objects that the text represents. At the second level of interpretation, the attempt will be to identify and fixate those things which are not plainly available for direct perception. Here the interpreter would look for things like emotions, sentiments, illocutionary effects etc which are not plainly visible. At this level, the idea is to get beneath the surface and see what remains concealed from a direct view. In fact, the second level is what is generally canvassed as interpretation. Now, the third level of interpretation, which is at a higher level of abstraction than the previous one. At this level, the interpreter will try to map and assimilate the text’s horizon of meanings to his own or her own horizon of meanings. The interpreter will make strenuous efforts at this level to measure and calibrate the world the text opens up with one’s own. Clearly phenomena like ideas, ideologies, evaluations and sensibilities will come to be interpreted. This is also the level at which most interpreters fail to do adequate justice because interpretation often runs the risk, at this level, of reading one’s own biases into the text. This is also because texts, as the philosopher Paul Ricoeur insightfully argues, offer “a paradigm of distanciation in communication.” According to him, “the text is much more than a particular case of intersubjective communication” because it involves communication across historical distances between people who shall never meet each other. For Ricoeur the very origins of the text are marked by what he calls the distanciation, that is, the text’s distance from the event of the discourse, from the author’s intention, from the original audience and finally from the constraints of ostensive reference. The text has the ability to stand by itself, as a completely secluded entity. The very fact that texts can be distant in this fourfold sense renders their interpretation necessary. The need to interpret will vanish only when the distance stands abolished. The abolition of distance would mean that the text ceases to be a text.

By Way of Conclusion

This is a vast area to reach quick conclusions, least of all in an article whose goal is to refocus our attention on how urgently we need to become hermeneutic. The above discussion offers sufficient proof that texts are complex entities, embedded in discourse, and that one cannot be flippant about their meanings or uses. Texts are hardly ever translucent, but are always shrouded in different layers of opaqueness and concealment. Therefore, no text can be spared the burden of being interpreted.

******

Cover image courtesy: https://www.endangeredalphabets.net/alphabets/sharada/

Bharani Kollipara is on the faculty of Dhirubhai Ambani Institute of Information an Communication Technology (DA_IICT), Gandhinagar, Gujarat. He writes and teaches in the areas of modern philosophy, political theory and South Asian Studies.

Leave a Reply