T

here was a heavy downpour over the city. From the unfinished roof of the seventh floor, it appeared that the traffic below had disappeared behind a veil of rain. Crouched on wooden planks alone, with a gunny bag to cover his head, Kartar Singh murmured, “Praise the Lord! Jo Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal! Timeless one. That is God.” It was as if by saying his prayers aloud, a heavy load had been lifted off his mind.

When the overseer had come upstairs in the afternoon to inspect the shuttering for the last roof, the sky was still bright and clear. Although there was a slight chill in the air, the mid-winter sun felt pleasant. The overseer had inquired, “Kartar Singh, when will shuttering be over?”

Confidently he had replied, “Rai Saab, you can send the steel fabricator tomorrow morning to lay down the bar-mats. My work is almost done.”

Officiously, the overseer had examined the wooden forms put together for the roof. He checked the supports under the forms, laid the spirit bubble across the planks to check the grade, pushed a few planks to ensure that they would be able to bear the weight of the rods and the wet concrete to be poured. Then out of curiosity, he had moved closer to the edge of the roof to glance downwards. Not fond of heights, the overseer had rushed down the ladder.

Teasing the overseer, Kartar Singh had remarked. “Don’t be scared overseer saab, with the Vaheguru’s grace nothing will harm you.”

Hiding his embarrassment, the overseer had told Kartar Singh to have his work complete by the evening.

Smiling Kartar Singh had shouted back, “Don’t you worry, God willing everything will be finished in time.” Kartar Singh was feeling light-hearted today. The early morning sound of the chimta and the rendering of kirtan hymns from his neighbourhood Gurudwara were still echoing in his ears. Since his childhood, visiting Gurudwara temple for prayers in Amrit Bela, the ambrosial hour, had become a habit that he greatly relished. This morning it was the first time while playing the chimta during the devotional chant, he had found himself drifting into a state of ecstasy.

The chimta was made of two shining steel plates, each a meter long, joined at a hinge. Each plate carried forty to fifty petal-like copper dishes, thin, tiny and round. The chimta, a magical percussion instrument was created for accompaniment during devotional singing. Each beat, through the clanging of steel bars created a hypnotic resonance that took over the sensory perceptions. The chimta like his carpentry tools had been with him as long as he could remember. While playing the chimta, in a jiffy he would be able to shut himself off from the outside world. Same at his workplace, at each strike of the hammer, the rhythmic sounds of the chimta and kirtan hymns would reverberate within, “Raam Simir Kar, Mana Raam Simir Kar”- Remember the Lord, Pray to God.

There was something unusually uplifting this morning in the high-pitched earthy timbre of the new hymn-singer, Raagi Jee. More he listened to him, Kartar Singh felt that Raagi was singing to him. HIs magical combination of words and music was such that Kartar Singh had a strong urge to rise up and dance like the Bhagats who used to visit the village in his childhood. He checked himself, continuing to strike the chimta to the beat of Raagi’s song. Before he knew what was happening, as his mystical journey continued, he saw visions of Gurdyal, Jasbanto and Bhuppi. One by one, they each moved close to him, yet remaining distant. Every time he would try to hold them, they would elude him by dissolving into the smoke of burning incense. The tears kept rolling down his cheeks.

At the end of the service, he had looked around for Ragee Jee. He wanted to share with him his brief moment of ecstasy, to find an explanation for the sudden rapturous experience. Before he could reach the outside courtyard, Raagi on his bicycle had disappeared into the distant fog.

“Those of seek Soul and Spirit

Will also seek out the God

There is only one nectar tree,

And all of us are the fruits of the same tree.” (1)

His favourite of the verses of his Supreme Teacher and Master. As in the verse, he always thought that Gurdyal, Jasbanto and Bhuppi were all parts of the same whole. He couldn’t understand then why, one by one each drifted away. How was it that their paths turned out to be so different from the one he had always thought laid down for him and other Raamgadiyas? No, his wife Jasbanto was not like either Gurdyal or Bhuppi. She had always stayed by his side. She understood his faith and beliefs. He could see Jasbanto in front of him – at the doorstep anxiously waiting for his return from the worksite; Jasbanto recounting to him Bhupinder’s and Gurdyal’s adventures of the day; Jasbanto sitting beside the cooking hearth serving food to all of them …

However with Gurdyal’s marriage everything changed. Gurdyal, his younger brother wanted to move out of the house, he was so unpredictable – abrupt and secretive. The same lack of trust Kartar had noticed, was now permeating in his relationship with young Bhuppi. He was unable to grasp why Bhuppi would trust his uncle more than his father, or was it just his imagination?

As with Gurdyal, Jasbanto’s departure was sudden and unexpected. But, unlike Gurdyal, she had not schemed or planned for it. Until the last moment she could not believe what was happening to her. For years even he kept wondering why Jasbanto of all people had to succumb to such illness that sucked out her life’s blood so quickly. Jasbanto in her practical womanly way had a great knack of patching the gulf between Gurdyal and him. She would have never imagined that one day Gurdyal and his wife Paramjot would take Bhuppi away from him.

It was strange that although Gurdyal was 11 years younger than he, he was now acting as if he were the head of the family. It was because of his newly acquired wealth that everyone now ran to Gurdyal for advice and decisions on family and personal matters. Everyone, including Bhuppi. Gurdyal, his wife, and even Bhuppi, they all still respected him, but he felt their acquiescence was a mere formality. He should have been stronger, and told them years ago that he could look after Bhuppi.

Some years before, Gurdyal, wanting his older brother to work in his new business, had hesitatingly asked him, ”Bhai jee why don’t you give up the shuttering work? There is little money in it. How much longer will you continue to be in the labouring class?”

The comparison of craftsmanship which has been learnt and passed over generations, to ordinary labour, Gurdyal’s words had pierced him like a needle. To Gurdyal, carpentry was just a commodity that could be bought in the market. But then to Gurdyal everything was for buying and selling — labour, craftsmanship, or officialdom. Kartar Singh smiled at his brother’s innuendo. He remembered how innocent Gurdyal had looked when he arrived from Phagwara. He was barely sixteen. Jasbanto used to tell neighbours, “Gurdyal is not only my Devar, he is my son too.” Kartar Singh was proud to have him by his side at the workbench. Gurdyal was going to be a brother, friend, and a co-worker.

But then one day Gurdyal did not show up for work. That evening Gurdyal announced that he had no interest in the carpentry trade. He had taken up a job with a Rohtaki building material supplier as a helper on his trucks.

Kartar Singh was stunned. He could not understand the reasoning behind Gurdyal’s decision in giving up the family trade. For generations, the carpentry had provided livelihood for the family. He had tried every argument to dissuade Gurdyal from taking the trucking job. He remembered his brother sitting silently, sullen-faced, determined not to return to the workbench.

This was about fifteen years before. Gurdyal now owned six trucks. He supplied building material for Delhi’s major construction companies. He had also bought a petrol pump. Across Yamuna, he had his own gas cylinder agency, being the sole distributor responsible for putting flame into the cooking stoves of East Delhi.

Who was right? Him or Gurdyal? At the strike of his hammer, once again the sound of Gurudwara’s chimta echoed in his ears, “Do not be vain about wealth or your physical beauty, both will wither away like paper. Praise the Lord, or you will regret. Pray to God, Raam Simir Mana…”

It seemed Gurdyal had the pulse of the city in his grip. He boasted these days of his sharp business instincts. “The job of a businessman,” he would often say,” is not how hard he works, but knowing what to buy and whom to sell to.”

Kartar Singh on such occasions wanted to shake Gurdyal by the shoulders, and tell him that the middleman’s work is nothing to be proud of, “to be a blackguard may be all right for pimps, but not for Raamgadiyas.”

**

The Raamgadiyas were well known in Phagwara for their carpentry skills and dedication to their trade. It was in Phagwara that Kartar Singh had learnt the practice of skills at the workbench from his older uncle, Taya. He could still remember the smell of fresh wood shavings in Taya’s shop. Seeing the full-sized saw in his tiny hands, Taya had heartily laughed, “O’ Kartarey you look like a little soldier.” He never forgot his first lesson in Taya’s shop. It involved the sharpening of the steel blades of the chisel and jack plane on the wet black stone. For Kartar’s confirmation as a trainee carpenter, Taya had donated the first chair made by him to the village Gurudwara.

Home. He had always thought he would return to Phagwara one day. But his village, in spite of so close to the city had grown from a hamlet into a town, and now it was changing into a city. Now that his Phagwara was no longer there, there was no point in returning. Years ago Taya had sent him to Jallandhar to learn polishing and joinery at the shop of one of his friends. He felt stifled working in the dark and dingy shops of the city’s narrow bazaars. It had not taken him long to find work outside at a construction site. The openness of construction sites had a refreshing feeling similar to that of the village. At first he installed windows and doors in houses being built in new refugee colonies at the outskirts of the city. Gradually, he started getting better-paying jobs as a trainee for the shuttering contractors, eventually to lay on his own the wooden and steel forms for the concrete roofs. Initially, these roof jobs were for only two or three floor houses. But as he moved to larger cities, because of his reputation as a diligent worker, the jobs of higher buildings started coming to him without difficulty.

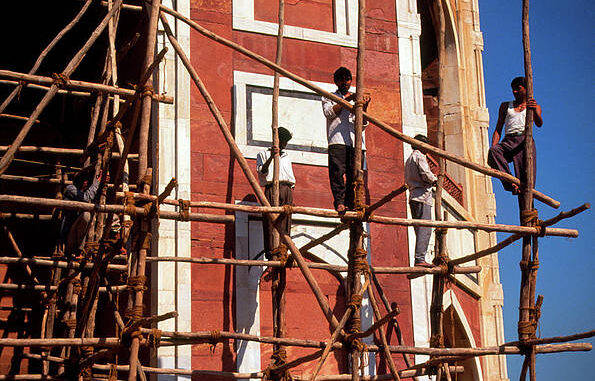

From furniture making to the task of a shuttering carpenter on a high-rise building was similar to that of having reached a mountain’s summit. On a multi-storeyed construction project, a new building grows within a net of scaffolding and flat wooden forms nestled together; these cling like a rib cage to the structure under construction. The cage providing the support is made of black wooden poles, three to four inches in diameter, tied tightly together by jute. On this vertical skeleton-like frame around the rising building structure, Kartar Singh walked with the ease of an acrobat. He was proud that over the past 25 years, the roofs of major high-rise buildings from Chandigarh to Bangalore had been laid by his expert hands.

Kartar Singh muttered to himself, “If to Gurdyal money is the most important thing, to me, the craft of my purbaj will be always sacred. How could Gurdyal be so inconsiderate? The whole episode of his marriage, for example, without consulting either Kartar or his sister-in-law, he had started discussions about his engagement to the daughter of a family of Bhappas. He had visited them by himself, and later asking Jasbanto to finalise the matter. Marriage to a Bhappa family. He had lost his temper at Gurdyal’s insolence. Are there no girls in Raamgadiya’s families? Gurdyal had spoken about the need for establishing ties with the Bhappas to expand his business contacts. According to him, Paramjot’s people were well-connected and influential, and that was enough. Even though they did not own much, all their relatives were high level government officials, contractors, and business people.

Kartar Singh was upset at his brother’s immaturity. “Gurdyal,” he had said in exasperation, “business and money is not everything.”

Jasbanto had interrupted him, “Why do you stop him? He is not a child anymore. If they are upper class, so what? Do not worry about Gurdyal. Whatever is written in his karma, that is what he must do, and that will happen.”

With a heavy blow, he drove the nail through the wood. Jasbanto was right. High or low, rich or poor, Bhappa or Raamgadiya these were man-made differences. For Vaheguru, everyone was a fruit of the same nectar tree.

In these years of driving nails through wooden planks, he had never once hurt his fingers. It was a matter of concentration. You only hurt yourself when you are inattentive. It is always envy, pride or anger that make you lose focus. At the strike of the hammer, he couldn’t stop himself from singing again Raagi’s hymn, “The wretched sinful mind runs after worldly goods, overnight everything will vanish, Praise the Lord, or you will regret, pray to God, Raam Simir Mana…”

There was a roar of flashing thunder in the distance. The blue sky had suddenly turned grey. From the other end of the roof, Kartar Singh heard his partner, Batan Chand, calling him, “Bhai jee, it looks like it is going to rain heavily this time. Come on, let us go down. How about a glass of tea together in the canteen?

Kartar Singh wanted to be by himself, high above, away from the clutter and noise of the vehicular traffic below. He replied, “Batane, you go. I will come after finishing the job.”

Before the clouds roared again, Batan Chand quickly stepped down the ladder. Kartar Singh felt some big rain drops on his forehead…two, four, eight, ten … and those drops slowly grew into a shower. He quickly covered his head with the gunny bag.

All by himself on the roof, Kartar Singh longed for this morning’s mystical experience. Through Raagi’s blazing eyes, he once again wanted to encounter Jasbanto. For a split second he felt he had seen Jasbanto with her untied long black hair, behind the veil of the rain. Jasbanto singing and dancing like his village minstrels with the chimta in her hands imploring him to come closer and join in singing. “Come on Sardaar jee, Raam Simir Kar, Phir Pache Pachtayega, Raam Simir Mana.”

In spite of his best efforts, he could not hold on long to Jasbanto’s image. No matter how hard he tried Gurdyal would keep intruding into his thoughts. He wondered at Gurdyal’s insistence. Were they not the children of the same mother? Then how could they turn out to be so different? In those early days he never questioned the differences between the two of them. He had attributed their tiffs and tussles to Gurdyal’s inexperience and youth but now looking at the past, he could see a pattern.

Soon after marriage, Gurdyal wanted to separate from the joint family. Kartar Singh could not comprehend Gurdyal’s keen desire to move into a rented place with his wife. A few years later, Gurdyal with success in business had been able to build his big house. He had through his sister-in-law Jasbanto inquired about their family to move in with them in the new house. Jasbanto had smilingly dissuaded him from raising the topic. “Gurdyal, Paramjot comes from an upper class family. We both have different ways of thinking. You never know when we two women might start quarrelling. I don’t want any love lost between you two brothers because of us silly women.” He had admired his wife’s tactful answer.

**

After Gurdyal’s move, it was young Bhuppi who kept the two families connected. Bhuppi was Gurdyal’s pet. He had been drawn to his uncle since childhood. When Gurdyal arrived from Phagwara, Bhuppi would remain glued to him. He would spend the day playing on his uncle’s shoulder pretending to be a horse rider. In the evenings, on Kartar Singh’s return from work, both of them would take his bicycle on rounds of the neighbourhood. Years later when Gurdyal started his own building-material supply business, he was so impressed with his uncle’s big Benz truck that he had wanted to follow in his footsteps. Gurdyal had jovially remarked, “Kakey dear, not only a truck driver, I will make you my business partner.” Seeing such affection between uncle and nephew, Jasbanto would say that Gurdyal would always look after Bhuppi like his own son. How prophetic those words turned out to be. So cleverly, both Gurdyal and Paramjot took Bhuppi away from him.

Sheltering from sudden downpour into a corner, Kartar Singh wondered if it was necessary for Gurdyal to have transformed Bhuppi into his own image. Even if he did not want to touch the God-given trade of their ancestors himself, he could at least have guided Bhuppi in the right direction. Had he forgotten the value Raamgadiyas placed upon one’s honest toil? For them it was through one’s craftsmanship that one worshipped God. Your karma and dharma, deeds and duties, and your ultimate salvation were intertwined with the kind of work you did, and how you did it. When he complained to Bhuppi about his frequent absences from the workbench, Gurdyal would immediately come to Bhuppi’s defense. “Bhai Jee, why are you always cross with this boy? He is in high school. There is a lot of school homework for him to do now. He just cannot be everywhere at the same time.”

Kartar Singh knew that school was merely an excuse. Whenever Bhuppi would come to visit him at the site, not wanting to dirty his clothes he would hesitate to pick up his father’s tools. Kartar Singh noticed subtle changes in the way Bhuppi dressed and presented himself. He was always wearing the clinging narrow trousers which though fashionable, were totally impractical for site-work. Like his uncle, he too had started wearing a pointed tight turban with a sharp angle in the middle, in the manner of city people. He would often see Bhuppi on Gurdyal’s motorbike, proud as a peacock, riding all over the city. He had noticed that instead of Bhupinder, Bhuppi had even begin to call himself “Bobby”. Like Gurdyal also, he had heard telling people that he was a Bhappa.

The changing of Bhuppi’s name was the cause of yet another heated argument with Gurdyal. Bhupinder, Gurdyal, or Kartar – these names had a significance and a meaning, they just couldn’t be changed like soap labels. Gurdyal had, as usual, felt the opposite way. He had thought it very sensible of Bhuppi to shorten his name.

“Bhai jee, Bobby is a very modern name.” Then affectionately slapping Bhuppi over the shoulder he had said, “My dear, we will get your hair cut, and make you into Mr. Bobby Singh. You have to get rid of this silly turban.”

“Gurdyal!” Kartar Singh had roared. He was shaking all over with rage. “Don’t you ever dare to give my son such advice. Is that all both you and your wife have been able to teach Bhuppi?”

Never had he felt so humiliated. He felt as if both son and brother had conspired to take revenge from his for a bad karma from a previous life. Seeing how distraught Kartar Singh became, Gurdyal had quickly slipped out of the room.

With no end to the rain in sight, Kartar Singh felt depressed. After all, Gurdyal was not a stranger. He was his younger brother. He wanted to throw out all the bitterness and resentment he had accumulated towards Gurdyal. How long could one be angry with one’s flesh and blood. He sighed, “Vahe Guru da Khalso, Sri Guru di Fateh ho. Victory to my Lord, I am thy dedicated servant.” He kept on repeating the chant. After Jasbanto’s death, he had become so deeply immersed in the holy Gurbani that there was no end to his prayers. The Gurbani, the early morning and evening sittings at the Gurdwara, recitations from Jap ji, Sukhmani…these prayers were like plunging into a deep spiritual reservoir from which he never wanted to emerge. It was so difficult to explain all this to either Gurdyal or Bhuppi.

Perhaps, if Jasbanto had been alive, things might have turned out to be different. He might have been more careful about Bhuppi, his son would not have to live with his uncle. During those first few months after Jasbanto’s passing he had completely lost grip on reality. When Gurdyal and Paramjot had implored him, for Bhuppi’s sake, his education, to let him stay with them, he had not been able to refuse them. Bhuppi had to be educated. Educated! He burst into a helpless laugh. Had his education not become a curse? It was strange that instead of instilling pride, education made you feel ashamed of yourself, your ancestry, your religion, your trade, and even your name. He knew both Gurdyal and Bhuppi had lied to him about the school. Bhuppi had long before abandoned his studies, and was now working full-time for his uncle. There was little excitement for Bhuppi at school, when compared with driving Gurdyal’s truck and motorbike around the city.

Bhuppi had recently let slip in that next year, in addition to the building material supply work, Gurdyal was planning to open a liquor shop. A liquor shop! Bhuppi had remarked, “Yes Daar jee, in Delhi, the license for a liquor shop is like a lottery, only the most fortunate are able to obtain it.” Before Kartar Singh could say anything, Bhuppi was trying to make him understand, “But Daar jee, selling and drinking are two different things.”

Kartar Singh had remained quiet.

**

This evening Bhuppi was coming to show him the new truck. Kartar Singh wondered if Gurdyal was behind all this, to coax Bhuppi to visit him. Or was it Bhuppi himself who had thought about showing the father his first truck? He had nothing against Bhuppi driving or owning trucks or running businesses like his uncle. He had learnt a lot during the past few years, you could not change anyone. Ultimately, it was only for his own actions that he would be held responsible. He no longer had any desire to mould or change anyone. He only wanted Bhuppi to understand his father: his beliefs, faith, craft and the true meaning of being a Raamgadiya. The Raamgadiyas were among the chosen few who had been blessed with the God-given gift of craftsmanship in carpentry. It was only a craftsman who had this unique capability of transforming a physical experience into a spiritual one through his labour.

Kartar Singh checked himself. He feared that Bhuppi as usual would twist his words into something non sensical and trivial. He would be only able to think that his father was a tradition-bound old man who was envious of Gurdyal’s prosperity, or that he was trying to put obstacles in the way of his youthful aspirations. Not wanting to turn this rare opportunity of a father-son conversation into another major disagreement, he changed his mind about such a confession. Instead, he decided he would talk this evening only about Bhuppi and his uncle’s business acumen.

Wanting to change the trend of his thoughts, he gazed below looking at the earlier city-traffic scene. The misty curtain of rain was slowly lifting. The traffic was gradually reappearing – a mishmash of cars, tuk-tuk scooters, tongas , and even some donkeys carting the dirt away from the building site. Kartar Singh lifted the gunny bag cloth from his head, and put it aside. In his crouched position, his kneecaps were getting sore. He stood up to stretch.

His whole body, the beard and long flowing hair were drenched in the rain. He took out the cotton gamcha from his tool box to wipe his face. While combing his beard, he gathered a large bunch of grey hair in his fist. It reminded him that in these eight years since Jasbanto’s death, all his hair had turned grey. The flow of life was like a river, who could stop that. Bhuppi would be twenty years old next month.

**

When he finished combing, he made a bun on the top of his head. He stuck the comb in it. He put the cotton towel back in the tool box. He then collected the folded trousers to put over his shorts. He again looked down wondering if Batan Chand and his other co-workers were on their way back to the roof. There was still some work left to be done. He put on his white, hand-spun turban, loosely around his head. Wanting to straighten it with one hand, as he was used to do, he reached with other hand for the tool box. But as he was reaching for the box, he was suddenly lifted off the roof by a gust of wind. The box in his left hand flung in the air, and the tools flew out all over.

Falling between the wooden poles, he kicked against the poles and the brick wall, rolling down. The road below with the traffic was rapidly coming towards him. But then, before he could shout, his shirt was suddenly caught on the scaffolding.

The emergency bell at the site began to clang. There were shouts all around. “Save Kartar Singh… Kartar Singh has been in an accident… Call the fire brigade, call the ambulance immediately!”

Seeing the huge scaffold slowly tumbling down, everyone was running away from the building.

It must be a miracle. Kartar Singh wondered. Trapped in between the two wooden poles, he tried to assess the seriousness of his situation. His unfolded turban had flown through the air and was now settled like a tiny ribbon on one of the poles below. His shirt, sweater, and trousers were all rags; he could feel the warmth of the fresh blood slowly oozing from wounds across his knees, elbows and back. Considering the depth of the fall, not much damage had occurred. He did not have much difficulty taking his tangled shirt and sweater from the wooden pole. He wanted to spread the weight of his body between the two poles, still tightly holding to the upper one.

Why was he not dead? It was difficult for him to believe that he had been saved. Was it for his right karmas: his vows to follow the right path and conduct all his life accordingly? Focusing upon such big questions until the fire-brigade arrived, he kept on chanting his prayers. During Jasbanto’s cancer, the life and death questions had several times raced through his mind. Was one’s life cut short in the middle because of one’s sinful living or pious deeds? On Jasbanto’s death, close friends and relatives expressing their sympathies had affirmed such thoughts, “It is those who have done good deeds in this or in a previous life who are called first.” Now it was his turn. He was not sure in this cycle of life and death, what should he pray for – life or death?

In the crowd gathering below, among those curious, upward-pointing faces, he thought he saw a familiar figure. Yes, it was his son. He smiled, Bhuppi must have come to show him his new truck. He could see him standing on the truck looking upwards, nonplussed. There was no contempt or rejection of his father in him, except a sadness that emanates from the eyes of a fearful child. As if Bhuppi wanted to say, “Daar jee, don’t leave me alone here. I am your son. My name is Bhupinder Singh Raamgadiya.” Kartar Singh choking with emotions, wanted to hold Bhuppi tightly in his arms.

Suddenly the pole on which Kartar Singh was resting, was unable to hold his weight further, creaked and began to split. Kartar Singh’s hands grasped the upper pole tightly, his legs desperately flailing in the air, as he looked for the missing support.

There was a loud roar from the crowd. The fire brigade man shouted over his megaphone, “Hold on to the pole tightly, Kartar Singh. Just a few more minutes. We are laying down this trampoline for you!”

“Oh my Lord, my Master, what kind of test are you putting me through?” Kartar Singh murmured to himself, “I regularly visit the temple, read scriptures, speak the truth, revere my trade, have I not done everything? As a husband, a father and as a brother, have I not fulfilled all my duties? Then why this game, must I go through this? He could not understand why a sudden longing to hug not only Bhuppi but Jasbanto, Gurdyal and Paramjot, this intense desire to have his loved ones by his side.

Tears and sweat welled up in his eyes. In that misty shroud, the burning red eyes of the temple’s Raagi jee were piercing him like two red hot rods. As if those blazing eyes telling him, “Good or evil, Raam or Raavana, no one has overcome death. The end comes to everyone and everything. Pray to God, or you will regret, remember the Lord! Raam Simir Mana, Raam Simir Kar.”

With his sweating right palm, he could no longer hold on to the wooden pole. Seeing his right-hand slip, the fire brigade officer again shouted to him on the megaphone, “it is alright Kartar Singh. Jump now! You must jump now.”

Kartar Singh could hear the echo of the morning’s chimta, steadily growing louder in his ears. He wanted to push the flood of tears out of his eyes. Like a tired swimmer, he felt he was about to jump into a bottomless lake. Suddenly his left palm left off its grip from the wooden pole. There was a loud scream. Kartar Singh’s body rushed past the scaffold.

His body bounced on the trampoline.

********

Khushwant Singh (1991), Hymns of Guru Nanak, Hyderabad, India: Orient Longman Ltd. , pp. 123 (Translated by Khushwant Singh and Illustrations by Arpita Singh)

--Translated from original Hindi story, KAAL-CHAKRA by Balwant Bhaneja, Saptahik Hindustan, New-Delhi, 27 January, 1991

Balwant (Bill) Bhaneja was born in Lahore and left India in 1965 for Canada. He has written widely on politics, science and arts. His recent books include: “Peace Portraits: Pathways to Nonkilling” (2022), Creighton University and Center for Global Nonkilling, USA; “Troubled Pilgrimage: Passage to Pakistan” (2013), Mawenzi/TSAR, Toronto; a collaboration with Indian playwright Vijay Tendulkar, entitled: “Two Plays: The Cyclist and His Fifth Woman” (2006), Oxford University Press ,India; “Quest for Gandhi: A Nonkilling Journey” (2010), Center for Global Nonkilling, Hawaii, USA. As a playwright, his works have been produced by BBC World Service (English adaptations of The Cyclist, Gandhi versus Gandhi), Ottawa’s Odyssey Theatre (Fabrizio’s Return), and Maya Theatre (The Cyclist), Harbourfront, Toronto. From 2012 to 2022, he was coordinating editor for peace and arts Nonkilling Arts Research NewsLetter(NKARC), Hawaii, USA. His short fiction is published in English and Hindi. A former Canadian Diplomat with postings in London, Bonn and Berlin, he holds a PhD from University of Manchester,U.K. billbhaneja@rogers.com

_______________

More by this author in The Beacon

Thank you for sharing this wonderful English translation of the original story in Hindi. I have had the pleasure of reading both of them and your English translation very aptly captures the emotions of the original piece. Like all your other stories, this too has touched me. The way you capture human emotions, very few can. Look forward to reading many more such stories.

I enjoyed reading THE SCAFFOLD. I like your details of Kartar Singh working on scaffolds and his adherence to the family trade. I was touched by the generational conflict depicted in the story. As I read your story, I was drawn to my own family’s history. My father was born into a family of goldsmiths and ran a highly successful jewelry business. He very much wanted me, his eldest son, to join him in his business and he was utterly disappointed when I decided to pursue a different career. What I am impressed with is your description of Kartar Singh on the scaffold are the details. These details showed me, Kartar Singh, in person instead of telling me about him.