T

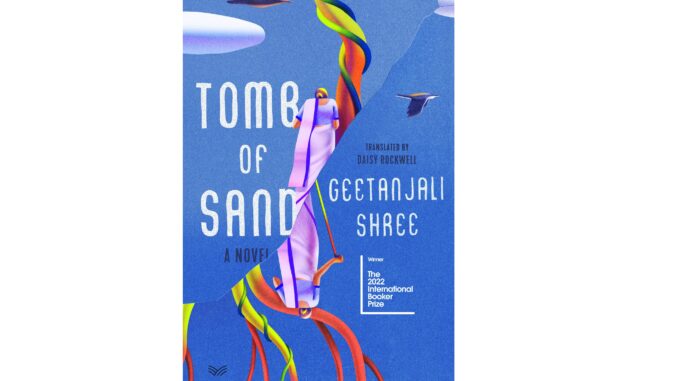

ry as I might to make a ceremonial tomb of Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand novel, I only ended up with sand. But there are interesting tomblike sequences and moments, so let us begin with these before the sand ones, unfortunately, overwhelm them.

In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Molly Bloom’s “yes” on the last page, “and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will yes,” gave a lot of hope to her marriage. It promised to restore potency to her husband Leopold and make the springs in her bed resound, once again, with joy. It was more definitive than that one-inch gap that separated the fingers of Charu’s and Bhupati’s marriage at the end of Satyajit Ray’s film Charulata. But Charu had provoked that enigmatic “yes” with her gesture and it was left for Bhupati to either close that gap and clasp her hand in “yes” or withdraw from it completely in the gesture of “No.”

In the first part of Shree’s novel, the eighty year old Ma has turned her back to the world in general and to her family in particular. “Ma’s respected “Nos” are splendidly offered as pointed contrasts to her daughter Beti’s adored “Nos.” As a child Beti “was made of No.” If she was told “eat the rice, not the paratha,” Beti would insist, “No, I’ll eat the paratha.” If it was suggested, “don’t go to sleep, keep your eyes open,” she would respond with “Noooo. I’m closing my eyes.” Ma learns from her daughter that an individual path suddenly opens up with a “No.” A much sought after freedom is gifted with a “No.” Her family and the world consider her “No” nonsensical, but it enables her to be her own person and, at the same time, reach a crucial “Yes.”

So she refuses to turn around and face her family even on the day of her son Bade’s retirement lunch. Her “Nos” shut her eyes to the flowers in bloom, refuse all open windows, ignore the sun (which even Camus’s Meursault could not), and resist all familial attempts to turn her feet to the falling sunlight. Then, on the day when her son’s government home is being emptied and all the furniture is being shifted to his new flat, Ma finally turns, lies supine on her back, and lifting her cane with the ascending colorful glass butterflies to a ninety degree acme of a triumphant “Yes,” she announces to everyone, “I am the wishing Tree” and vacates her customary presence in her son’s home to go and live with her Beti from whom she has gained that strength of “Yes,” and finally start a new life, distinctive and distant from her nagging middle-class joint family.

In the second part of the novel, “because of the new cane, if it hadn’t come” (as a gift from one of her grandsons) “then Ma wouldn’t have picked it up, and she wouldn’t have been able to lift herself up” to that crucial “Yes.” After going “missing” for “thirteen days,” she is found smiling at her anxious family in the police station where the actual pronouncement of her resounding “Yes” takes place just when the family is determining “to prepare Ma for a new life” in her son’s new flat. “Let’s go,” she thunders to her Beti. “Right now.” This “now” not only replaces the “No” but also substitutes for it a “new” beginning. The “knots” that tied Ma to her family “like the old shoelace” are all “gone and there is a new horizon” ushered in this embrace of mother and daughter who have dared to rebel against their family in such a theatrical, but crucial manner.

In her son Bade’s home, Ma slept, was inert, and didn’t bother even to stir. In Beti’s home, she “starts to swing,” not only literally on a swing, but also figuratively from the balcony, within each room, and even on the potty in the bathroom where she enjoys breaking wind. In these new surroundings, she can celebrate her companionship with her transgender friend Rosie openly and the pleasing joint family of food, “dal with roti and sabzi” combined with the “company of ghee, chutni, salad, raita, and a little rice” has never tasted to good.

“The goddess of work” who slips in softly to sit down beside the author, now makes “the pen rise by itself and as it begins to move” (like Omar Khayyam’s rubaiyat-writing finger and Michelangelo’s sistined-extended one) “across the page,” “a story a book begins to take shape,” but soon it begins to falter, tremble, and then cracks start to appear. They multiply as the narrative advances and we are left with lots of sand, lots of sand, besides the careful and inventive spread of ink, lead, papers, and a leaking tomb.

The stream-of-consciousness technique is what the novel is entombed in. Its aims are noble and daring. Borrowing its clue from Dostoyevsky’s underground narrator, it does not want the story or the reader to “become a prisoner of two plus two is four.” It wants us to respond without “the capabilities of (our) grasping greedy sluggish rag tag stagnant jalebi brain” but with “every part of our bodies” to the “subtle reverberations of sound and meaning.” But something goes wrong in the noble enterprise.

Stream of consciousness narrative is selective. It is dependent on the sensibility of its chosen characters. The subjective perspectives, so assembled, then add variety to each distinction.

But in Shree’s novel, distinctiveness and perspective are deliberately blurred. Oftentimes a character, or even the omniscient narrator, is interrupted for no apparent reason.

The most intriguing is the presence of a marginal narrator who first appears on page 351. He literally “takes the mic from the people saying nonsensical things about desi and American accents, so they’ll stop talking and I can begin my own narration.” He’s a friend of Sid, the family’s American overseas son, and “swinging straight…on fragments of sunlight,” he accompanies Sid to “surprise Granny.” After “barging my way in again,” and offering an unnecessary comment on the Salman Khan incident of driving his car over some pavement-dwellers in a suburb of Mumbai, he strangely disappears. Just before he exits, as abruptly as he had entered, he admits he’s “got nothing to gain or lose from the story.” Then why is he included in the story to begin with? He turns up, again on page 494. “Sid was there, and since I had driven him there: yes me too,” he accompanies Beti and the other family members to find the missing Rosie. After that we don’t hear a single word from him. We find him missing till the last two pages of the novel, pages 738 and 739 when he appears again. “Even though Sid and I no longer work together, I’ve gotten used to hanging out with his family” in India. But why? No compelling reason is given as to why this family would even have made an effort to adopt him. So, he ends up “ignoring” everyone and confesses “I don’t belong here and it isn’t my story. I’ve entered it, but what character am I? I don’t belong.” Then why does he intrude and interrupt the narration?

And why does the novel have to end with him and his longings for “leaping out of a window” or to “fill with color some corner of the canvas.” He seems to be the least likely candidate to do either.

A big problem manifests itself it seems to me, with the problematic inclusion of the crows. For Bade to climb a tree, hide in its protective foliage in order to spy into his sister’s flat is in itself absurd. That would be convincing in a Fellini film, but not on a street in Delhi. And to have him seen by a crowd of crows and then conferenced upon does not work at all, even on a meta-fictional level.

Read about the crows here: Excerpt from Tomb of Sand/Ret Samadhi: Geetanjali Shree

And if this moment is meta-fictional, it seems to offer itself as an indulgence on the part of the author. The question that begs itself here is why crows? Do they have a special metaphorical significance in Hindu culture in the way Edgar Alan Poe’s “The Raven” signifies for the poet “mournful and never-ending remembrance” ? We had a Sindhi neighbor in our Poona chawl who, every afternoon, fed crows by throwing leftovers and other food on the tinned roof of our backdoor’s staircase. And there is that other popular reference to crows in the Hindi film, I think, it is Bobby: “Jhootbole, kauva kate/kale kaube sein duriyoo.”

Why will crows bite us if we tell a lie? Why should we be afraid of dark crows? They even seem to have seen the film Gumnaam where they identify completely with the dark skinned buffoon’s (played by Mehmood) song: “Ham kale hain to kya hua, dilwale hain!” Jacknapes, the reformed crow will in fact, fly thousands of miles to become Ma’s best friend in the prison yard of Khyber, and after she is killed, will fly a thousand miles back to become Bade’s soul mate in his old age. His flight is resorted to like a compulsive pilgrimage he has sworn to make to comfort these human beings.

But what are these crows, singular and plural contributing to this family’s history? What significance, if any, are they adding or subtracting from the narrative? Or is this, once again, merely an exotic authorial imposition?

The absence of a well-defined plot puts a heavy insistence on executions of different stylistic incursions. But when they are repeated over and over again, they become quite tedious. Many times this leads to a kind of self-indulgent “showing off” by the writer. It seems to demand some kind of applause, like, for instance, her knowledge of the different saris worn by Indian women or the many secrets she is willing to reveal about cooking different varieties of Indian cuisine. These would be welcome if they emerged from within the confines of the plot where a moment, a situation, or a character, is anchored in them.

But in a plot-less novel, it becomes ornamentation, and when it is repeated, it turns into a habit unnecessarily drawing too much attention to itself.

In her translator’s note, Daisy Rockwell alerts us to the fact that “the original novel is artificially Hindi-centric, just as the translation is artificially English-centric.” While this is true, many times, in the tension created between these two centric modes, the English version fails to communicate the Hindi version and this happens because the translation fails to understand the culture in which that particular utterance or statement is being offered.

Let’s begin with the liberal peppering of the term “dude” that is pronounced by so many of this middle-class family members. This American expression, I don’t think, has taken roots so frequently or so firmly in today’s India. The only family members who would use the term in India would be the American overseas son Sid, and maybe his brother who has settled in Australia. It is very unconvincing, for instance, when Beti tells us that her mother is foolish “while yukking it up with murderous dudes over cricket.” Used by a practicing journalist, this entire phrase would have been blue penciled. Even the work “yukking” is problematic, because like “dudes,” it comes from American slang. Beti had shown no preference or partiality to American speech elsewhere, so why would she use it here, especially in her nervously frayed condition as a prisoner in a Khyber courtyard. In fact, the translation in the Pakistani section of the novel is very clumsy and careless. In the interrogation sessions we are told that Ma “gives wackadoodle answers.”

Wackadoodle, again is an Americanism. It comes from the American comic-strips linguistic universe and reduces Ma, wrongly, to an American cartoon caricature.

At other times, a description takes on a peculiar Victorian English intonation like this one, “Far off, on the street, screech the tires [even the word “tires” is spelled in the American way where no difference is ascertained in the spelling between the noun “tires” and the verb “tired”] of numerous trucks, but these leave nary a trace on the silence.” The word “nary” was a common one in nineteenth century English fiction, but here it seems antiquated and completely out of place. Another Americanism occurs, as in this phrase: “But the rains have already started. Why water the plants? Beti objected, raining on Amma’s picnic.” To rain on someone’s parade is an American expression and is clumsily offered here as an Indian idiom to emphasize, or maybe enhance, the rain metaphor. And if it manages to do so, it does it very clumsily.

Family sagas tend to cough up a lot of philosophy, introspection but finding it in Shree’s novel proved a futile task; all the characters are so firmly steeped in their mundane middle-class existence. None of them, therefore, are capable of indulging in any kind of ruminative discourse. None of them, also, have undergone any profound crisis that usually brings forth existential meditations and concerns. The abyss, where most of these occur, hardly beckons them to speak like zarathustra. When Ma feels overwhelmed, she does not philosophize on Wordsworth’s “the world is too much with us” expression. She merely turns her back to the world, faces the wall of her room and simply shuts her eyes. She does it with the full intention that she will be dutifully looked after. She is not homeless or out on the street. When she does face the world, she moves to her daughter’s flat, has tea every morning on the balcony, waters the plants, scolds the gardener, instructs her maid, and spends happy hours gossiping and embroidering with Rosie.

Compare her to Steinbeck’s Ma Joad from The Grapes of Wrath. One can immediately discern her as a reflective character because she suffers so much on a daily basis. When her daughter’s nipples have shriveled up and her wailing baby has to be fed, Ma Joad will find a way of getting that milk, warming it, and feeding her grandchild. Then she will sit at the kitchen table and discourse with the reader on her three generations of family’s tragic displaced condition.

None of Shree’s family members are capable of doing this. They all live such superficial lives and they seem, ironically or otherwise, so content in them.

Bahu after her daily dosage of quarrels with her husband does not become introspective when she puts on her Reeboks. She does that only to do yoga in the park. Beti has her cup of tea, works on her few articles, and wonders if she should take back her flat’s key from her lover KK. Then she opens her bathroom cabinet and ponders what new shampoo to use. Bade meets his government friends, goes to the bank, and visits his mother only when he needs her signatures on shares to invest. The reader gets no glimpses into the characers’ interiorised lives, into their individual or collective consciousness.

Regarding the all-important question of “borders” and “boundaries,” most of the time, the characters are content only to cross the borders and boundaries of their rooms. Rosie, who does cross gender boundaries, appearing on some days as a man and on some days as a woman, is the only character who, very curiously, is not only denied any opportunity for philosophical speculation, but is also refused a baptism into the stream of consciousness. Her sole existentialist rumination is uttered at the hospital when she is ministering to Ma. “One must live through thousands of days to reach the dying day.” But any profundity that this utterance might contain is rudely undermined by it becoming as popular an aphorism as the dacoit Gabbar Singh’s remark from the film Sholay “Arre, oh Sambha, kitne admi the?” The dacoit had used that as a taunt to cast aspersions on Samba’s impotent masculinity. What Rosie was referring to is never expounded upon. And not once does she ever talk about her transgendered existence and appearance or way of life.

Ma, with Beti, does cross the border that separates Pakistan from India. She goes there, in the novel’s final section, in search of Anwar, her Muslim lover, and since both women are travelling without visas [how did Beti ever agree to such a necessary violation?] they end up as prisoners in Khyber where Ma seems to suddenly “flow in so many directions.” We see her more alive in Pakistan than she was in India. Her amazing growth is then contrasted with Beti’s subsequent decline. Beti becomes exactly like Bahu. She feels abandoned and neglected by her mother who seems more at home with her captors and a crow.

Ma’s astounding nine rasa enactment speech about borders is thrown at us completely out of the blue. Where could this matriarch have gained so much knowledge about this complex subject? And why was she so silent never mentioning it, even once, when she was living her complacent settled existence in India?

One can only discern the omniscient narrator here pulling Ma’s strings. Ma has not and is not suffering enough and is therefore not capable of making and enacting these remarks.

Similarly, when she finds her lover, now comatose and paralyzed in the home of Anwar junior [who could be her son], she, bursts out into Raga Puriya– again, out of the blue! She had never sung, not even once in Beti’s flat in India, and had shown, in fact, no interest in any kind of sangeet. What she had produced there was merely a whistle to accompany the birds who sang at her window. This raga, unfortunately, is now suddenly offered as a stylistic trope to enhance the narrative. The first line “aa re kaaga ja re” is addressed not to the invalid lying beside her but to the crow listening outside. He is the messenger chosen by Ma to send her “sandeswa” or tidings of love to her “piya,” her lover, who went away to “pardes” leaving her sleepless and helpless. The trope is clever but fails to typify or justify, both her human condition and her crucial presence here beside her invalid lover. More ragas astonishingly escape from her lips till they extract the single word of “forgiveness” from the invalid. “You didn’t come, Ma said, I forgive you. I didn’t come, do forgive me.” The ragas forgive her trespass and those like Anwar who trespassed against her. But why did we not learn anything about these ragas in India? Musically, why was she so compellingly silent for over eighty years?

So much sand leaking out of that tomb robs the novel of a kind of majesty, which should very clearly be there. Even Anarkali agrees with me when she read this novel and laughed and wept in her tomb. Saachi, Pyar Kiya to darnakya!

*****

Darius Cooper is an essayist, poet and film critic. He has written on Guru Dutt, Satyajit Ray and published essays and reviews in India and USA including The Beacon.. “Aavaan Jawaan” is his latest collection of poems. He is an editor with The Beacon webzine..

The author in The Beacon

Leave a Reply