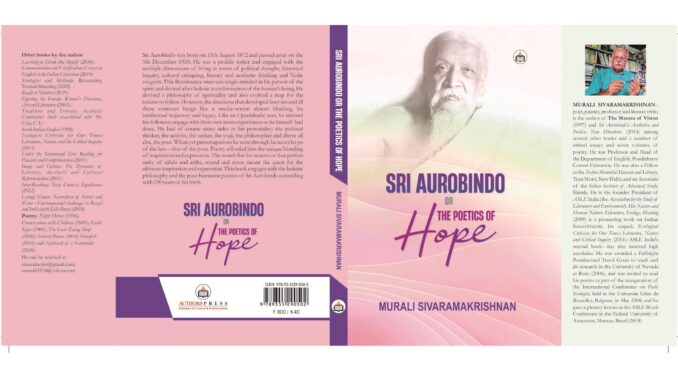

Sri Aurobindo Or Poetics of Hope. Murali Sivaramakrishnan. Authorspress June 2022 157 pages

Author’s Inroduction

T

his is indeed a time for introspection–even for the common man and woman. Our ubiquitous social media is flooded with quips, quotes, citations and aphorisms reflecting upon, exploring and explaining life. However, philosophers and mystics, scholars and poets, have always and at all times, been struggling with such fundamental questions of existence in profound seriousness. The inner quest for meaning has perhaps created a graph toward a perennial philosophy. And of course only the ardent and the inquisitive mind has been able to trace this graph of hope. The journey toward the interior spaces leads the seeker into the lesser trod dimensions of spirituality, but once initiated into these levels, the genuine inquirer is certain to meet with innumerable like-minded seekers. Sri Aurobindo (1872-1950) was ceaseless in his inner search; for him self-reflexivity came naturally.

Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy and poetics were intricately connected. It is a spiritual aesthetic that he proposes. The chapters in this book argue that Sri Aurobindo’s spirituality needs to be seen in a global perspective; it was as much part of his social and political consciousness as it was of his religious, His ceaseless endeavour to view life in its totality, and to see it whole, signifies the most outstanding fact about his spiritual standpoint. Right from his earliest contact with the Indian situation which came only as a second phase after his exposure to Europe, Sri Aurobindo—born as Aurobindo Ghose– was convinced of the legitimacy of an integral awareness. And what he came to identify as the two negations —the materialist’s denial of an eternal Being behind the phenomenal and the ascetic’s refusal to accept the reality of the world—were, as he saw it, the two major impediments both to a comprehensive awareness and affirmation in the history of human thought and a new and rich self-fulfilment in an integral existence for the individual and the race alike. He sought to integrate life and spirit into a cosmic whole and to embody the unified vision in an ascent to Gnostic humanity. This call towards an integral attitude might also be traced to the apparently contradictory nature of his historical situation.

Born in India and brought up in England, the prophet of militant nationalism and the silent recluse of Pondicherry, the Yogi of the ancient Vedic temperament and the author of a prodigious variety of writings in the English language ranging from songs and sonnets to narratives and epics, from political pamphlets to philosophical treatises, he combined in himself both the West and the East. To understand his philosophy and thereby appraise his aesthetic theories which are organically unified with his philosophical insight, we have to take into account the impact of both the West and the East–the “Indian impact” because Sri Aurobindo deliberately chose to be an Indian.

Sri Aurobindo was born on 15th August, 1872, in Calcutta, as Aurobindo Ackroyd Ghose, the third son of Krishnadhan Ghose and Swarnalata Devi. It was a time when hundreds of years of stupor and languor permeated by inner conflicts and turbulence in the Indian scene had resulted in the consolidation of British colonialism, and concurrent to it, a new upsurge of national ethos was in the process of crystallizing.

[Snippet Indent]

But he confronted the question of what it meant to be an Indian only much later, when he returned from England, a fiery young man of twenty-one, seasoned in European classical learning, well-versed in Greek and Latin, and eminently ratiocinative.

His early writings in the Bandemataram and the Karmayogin about India and her heritage were more of a justification for his national identity of which he was only slowly becoming aware, and a violent reaction against the colonized experience. But later, as his politics took him deeper and deeper into the very heart of nationalism, and his reading revealed to him the essence of Indian wisdom, he, despite the inner pressure in him to identify with what was a partisan view, chose an integral cosmic stance. This is what makes Sri Aurobindo, as Shankar Mokashi Punekar has said, “a unique phenomenon.” For,

“He is not a mere product of the Hindu resurgence, he brought to it a creative continuity with European thought.”

Everything that he wrote argues not merely for the integral conservation of higher values of existence, but also for a progressive increase of the levels of being, and the increasing progression calls for a new heaven and a new earth. Similarly there is evidenced a radical difference in his later mature writings as they are naturally the products of a qualitatively higher order than the earlier work. However, there does endure a discernible design for a massive visionary and critical structure in Sri Aurobindo’s earlier writings to be constantly and periodically modified and developed later. He was never a systematic philosopher though. His writings bear testimony but to his deep-felt inner experiences. They embody the essentially poetic vision of a Rishi, seer-poet.

His aesthetics is inherently implied in the creative experience of reality and not an aesthetic theory that is inferred intellectually and systematically. Hardly can it be said of any other poet or philosopher as can be said of him that they lived their poetic visions.

In sheer bulk and variety of subjects, his creative output is stupendous: apart from translations from Sanskrit, Greek and other languages, social and political writings, philosophical treatises, speculations on the Veda, Upanishad and the Gita and massive volumes on Yoga, his work includes two epics and some two hundred odd poems. He undertook all this without any appeal for public recognition, literary acceptance or social status. A quiet man with a serious disposition and an intense passion for literature and thought, Sri Aurobindo was, as Romain Rolland chose to describe him, “the most noble representative of the Neo-Vedantic spirit… the foremost of Indian thinkers,” and also, “the completest synthesis that has been realized to this day of the genius of Asia and the genius of Europe,” and the last of the great Rishis who held in his hand “in firm and unrelaxed grip, the bow of creative energy.” Anyone who came into the circle of this creative personality experienced a strange mystic rapture, the extreme form of which Dilip Kumar Roy noted:

I can only say that in his presence I felt myself gripped by a silent wonder and intense longing to lay my utter self at his feet and lie cradled in his indefinable Grace.

Variously compared with Hegel, Bergson, Bradley and Heidegger and classed with Radhakrishnan as a notable philosopher, with Gandhi and Tagore as a leader of modern India, and ranked with Sri Ramakrishna and Maharshi Ramana as a saint, Sri Aurobindo’s life falls into three distinct phases. At the age of seven he was taken to England and with his coming back to India in 1893 the first European phase ends and the political one begins. Seventeen years of militant nationalistic activities landed him in jail where the most significant experience of his life occurred—a mystic vision of Krishna-which brought in an entirely new dimension to his life and work. Although this event marks a turning point in his life and the beginning of its third phase, the earlier experiences were but preparatory to this. The developing life of a true mystic traces a gradual ascent in the scale of experience and values; Sri Aurobindo’s life is rich and complete in its many-sided development and follows a clear pattern of ascent and integration.

From the Cambridge scholar through the militant patriot to the silent Yogi of Pondicherry it delineates a qualitative transformation, integrating everything which has gone before into a higher plane of consciousness.

With Sri Aurobindo the conventional division of the outer and inner world, subjective and objective reality, is no longer meaningful. To him action was the essence of life but it did not mean a turbulent agitation on the physical plane; it was an action that came by a conscious subjection and merging of the ego in the divine Self, a liberating action. “When we strive to act, the forces of nature do their will with us,” Sri Aurobindo explains in an early article, “when we grow still, we become their master… The more complete the calm… the greater the force in action.” To the man whose intellect is delivered from the enslavement to dualities, from the oppositions of inner and outer, silence is the superior action—the accent is on “being” rather than “doing.” Thus the “action” of the “superior man” often stands apart in a clear variance from the ordinary.

And as a man who “knew.” Sri Aurobindo left politics as suddenly and unceremoniously as he had come in. For a writer in whom the man and the work are necessarily one, this transformation from the militant political activist to the self-exiled recluse calls for closer attention.

Sri Aurobindo passed thirteen years, from 1893 to 1906, at Baroda working in various government departments and later teaching French and English in the Baroda College. These were years of self-culture, literary activity and secret political engagements. He studied Sanskrit and other Indian languages, assimilated the spirit of Indian culture and civilization, and in 1904 began practicing Yoga, starting with pranayama as explained to him by a friend, a disciple of Brahmananda. There was, as he found, no conflict or wavering between Yoga and politics—when he started Yoga he carried on both without any idea of opposition between them. In 1908 he met Vishnu Bhaskar Lele of Gwalior, who advanced him further in Yoga giving him a greater insight, strength and faith, and more confidence in himself. By this time he had left Baroda and taken up the position of the Principal of the newly founded Bengal National College in Calcutta. Then on till 1907 when he was arrested for sedition and later acquitted, he wrote and spoke for a new national awareness, preached a militant activism and meditated on God and man. The Bandemataram, the newspaper and weekly that he jointly edited with Bepin Chandra Pal, carries the bulk of his early political pamphleteering prior to being prosecuted; the Karmayogin and the Dharma, in English and in Bengali repectively, which he edited single-handedly, following his acquittal, sound a markedly different tone from these early rebellious incitements—they reveal the workings of a mind and an inner spiritual energy pressing upon it for an exclusive concentration. In a speech delivered at Uttarpara on May 30, 1909, published in the Karmayogin, he gave utterance to his remarkable spiritual experiences in the Alipore jail.

As the walls of materiality crumbled around him revealing the omnipresence of Krishna, Sri Aurobindo underwent an experiential conviction of all that he had earlier gathered intellectually from his readings of the Gita, the Upanishads and the Vedas.

This experience convinced him of the fact that all beings are united in One Self, but divided by a certain separateness of consciousness, an ignorance of their true self. He found that it was possible through certain psychological disciplines to remove this veil of separating consciousness and become aware of the true Being, the Divinity within and without. In Yoga, Sri Aurobindo found a means of inward living and transformation.

In Sri Aurobindo’s vision the theoretical is bound up with the practical—gnosis and praxis– the metaphysical is integrated with the psychological. His philosophy is not an abstract theoretical system but a concise register of his experiences, and his finding that certain mantras of the Rig Veda substantially corroborated his own experiences strengthened his conviction of their validity.

******

Murali Sivramakrishnan--poet, painter, professor and literary critic, is the author of The Mantra of Vision (1997) and Sri Aurobindo's Aesthetics and Poetics: New Directions (2014) among several other books and a number of critical essays and seven volumes of poetry. He was Professor and Head of the Department of English, Pondicherry Central University. He was also a Fellow at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Teen Murti, New Delhi, and an Associate of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla. smurali1234@yahoo.com; smurals@gmail.com

Leave a Reply