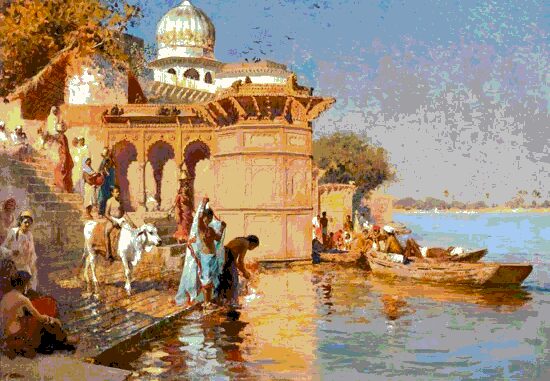

Representational Image. Along-the-Ghats-Mathura-1891

Translated from Gujarati by Hemang Ashwinkumar

‘Help, help!’

A wild uproar disrupted the familiar rhythm the ghat had happily settled into; the small, bat-shaped clubs, heaved up to beat soaked clothes, stilled in the hands of women. Earthen and metal water-pots, filled to the brim, froze mid-air in the hands of the village girls who were about to place them on their heads. The scrubbers scouring household vessels turned into bronze-pale statues. “Dear me, what happened?” “Hey, tell me, what is it?” “What’s the matter?”- edgy questions hovered heavy in the humid air. Everybody gaped blankly at the couple of panicked women who, having stepped as far into the lake waters as their courage permitted, were letting out agonized cries, their hands outstretched, and faces daubed with horror. “Hold her, O dear me, somebody hold her!” Their state of acute agitation notwithstanding, the women stood rooted to the last couple of steps of the ghat, unable to budge even an inch and offer a hand to the drowning figure. Horrified, they began to tremble like a leaf, too scared to grab hold of the end of the red sari, floating just fifteen feet away from them in the heaving waters.

One of the village women, who routinely came to the ghat for washing clothes, had probably slipped off and was sinking now; the end of her sari snaking its way into the rippling waters led the onlookers to guess as much. All eyes now turned towards the focal point of the uproar. Questions like “Who’s she? Who’s that woman? began to be asked.

“Madho’s wife…the poor woman slipped in, it seems.”

“Oh! Please call somebody!”

Just then, the body of the woman surfaced on turbid waters, her head shook slightly and sank again leaving behind a trail of gurgling, bursting bubbles. The shock of her loose hair floated for a while and disappeared, like the tail of a serpent slithering into its hole. A shudder ran down the spine of the spectators; exclamations of “Good God! Holy Mother!” tripped off their gaping mouths.

Wild with worry, the victim’s mother-in-law and young sister-in-law began to beat their breasts squatting amidst the litter of clothes on the last, unsubmerged step of the ghat, and weep hysterically.

“Somebody save her, she is drowning!” young girls, standing on the footpath beyond the steps, screamed blue murder.

Just then, something like a flash, a slight quiver, a quick movement drew all the eyes; something slid speedily underwater from the side of the ghat, though nobody could clearly see what it was.

“O God! A croc!” a hysterical cry rose as all panicky women sprinted for the safety of upper steps.

The body of the drowning woman surfaced and sank once again. Someone, standing afar, cursed helplessly. In the meantime, an experienced woman, seeming to have some expertise on the mechanics of drowning, announced coldly,

“The body will surface once again, one last time. Mark my words.”

“Forget it. It’s all over now.” Somebody snapped, rudely biting her off. Just then, the supine, curvaceous body of the woman came up and began to float on the shimmering sheet of water. For many among the bunch of captive onlookers, the scene of drowning, which commonly excited feelings of terror, curiosity and sympathy, was a matter of awe and wonder, a rare spectacle one gets to see in a lifetime.

“There she is!”

But this time round, she didn’t sink; on the contrary, her body remained afloat on the water, and began to drift on its own towards the ghat. After a while, a head, with a shock of black, glistening hair came into sight. And before the audience could figure anything, the horizontal, linear figure and the black head, like a dot at its centre, reached the steps of the ghat. Everyone heaved a sigh of relief. The brave man came half out of the water, sporting his muscular body bare up to the waist, and stood on the steps of the ghat. His dark drenched form was awash with bright sunlight. With the supine body of the woman in his black sinewy arms, as he began to climb the steps regally, one by one, her comely torso in sanguine silken blouse, her symmetrical fair face with aquiline nose and long silky hair emerged out of the water in full view of the onlookers who looked stunned and bemused at the same time. The woman’s pale right hand, set off by a shiny, scarlet bracelet and legs laced with silver anklets, dangled lifelessly in the air. The man looked unearthly, like a Naga prince rescuing Goddess Lakshmi from the nether world.

“All right, somebody cover her up!” he issued a directive as he gently laid the woman on the ghat, his voice metallic and commanding; then, he began to wring water out of his tucked dhoti.

“Please bring her further up on the ghat, bhai.” somebody pleaded.

Virtually shellshocked, nobody could dare to go down the moss-ridden steps, so the man obliged. “Now take her home.” he instructed nonchalantly, turned back, and like an aquatic animal, straight out of the Water Age, slithered speedily in the heaving waters.

“Who was he?” a young girl asked, unable to contain her fascination and curiosity.

“Damn you, keep quiet!” a fortyish woman, standing next to her, chided her right away, but then whispered into her ear, “Didn’t you recognize him? That damned…!” A mischievous smile on her face, she swayed her hand naughtily and said, “Come dear, let’s go home now.” While leaving, she ogled sharply at the receding head of the swimmer that had reached the middle of the lake by now.

The in-laws of the woman carefully covered her frame in a sturdy cloth, laid her on a string cot and escorted her home. As they left, somebody perched on the chotro – the sprawling plinth-level, brick-and-mortar platform, built around the trunk of the bunyan tree on the ghat – said grimly, “This lake won’t let the village breathe in peace until it takes its toll, oh no.”

“But there must be some remedy for it, some way to break the jinx?”

“May Mother Ashapuri ward off the evil! If you want to save the village, try making this Amro the holy messenger to Mother. Otherwise, you see, the spirit of the lake has come alive, and it won’t rest easy without claiming what is due to it – a human sacrifice.”

Someone cut in, his voice low and funereal, “This is not a good omen, nah. The earth’s prey has escaped her mouth. Now she may take two or even four sacrifices in lieu of one, who knows?”

The swimming head had reached deeper in the sprawling lake; the head with dense curly hair, protruding forehead, slightly jutting chin, pointed nose, slim purse-up lips and emerald earrings. However, only someone with an eyesight as sharp as his own could have seen these minutiae from the bank of the lake. To the people on the bank, the swimmer’s head, catching the sheen of the afternoon sun and slithering in the ashen waters of the vast, platter-like lake, looked like a dark-blue lotus gently swaying in the wind.

The village women who had come to the marble-floored ghat for sundry chores disappeared gradually. From the shimmering depths of the lake, those women looked like fairies to Amro’s languishing, youthful eyes. The women busily moving about the ghat, saris tucked at waist and legs ravishingly bare; the women letting loose a mellifluous ringing of bracelets and bangles in concert with their thumping wooden clubs; the women burnishing their copper and brass vessels with buttermilk; the women filling refulgent water-pots and hoisting them on their delicate heads; the women on their way home, untucking their saris and letting loose the splendor of accordion pleats. Feasting on such elegant, erotic spectacle was possible only from the middle of the lake, nowhere else.

Till today, the star-crossed swimmer had kept watching this world of village ghat from the social distance, ordained by the law of birth; for him, it was a remote, mirage-like world, a world of fairies. Sitting on the low ghat on opposite bank of the lake – his haunt –, or thrashing about right at its center, his enthralled eyes followed the vanishing glitter of every pot and pail. Those pots, those women, those bracelets, those swaying hands, those fluttering saris, those blooming youths, those houses, those swings, those cots and those…those…Thinking of all that, his mind went numb. He would dip into the waters to forget what he could see but never touch. Sometimes he felt like going to the bottom of the lake and kill himself by getting stuck in the mud. Distraught, he would take a dip, go right up to the bottom, and come up with fistful of mud. But who was there to appreciate this brave feat, this matchless skillset? Nobody. Crestfallen, he would open his clenched fist, see the mud dissolve in water and the water assume his own muddy complexion. When the loneliness became too much to bear, he would quickly swim his way back to the other bank taking the lake’s breadth in the wide sweeps of his bare, sinewy hands.

The ghat meant for the cultured women was off limits to him. There were ghats on the lake, comparatively small and shaded by trees, reserved for lowly communities of the village. Ebony dark wives and children of koli and baraiya families would throng those ghats like naga sadhu, dive into the water, swim and splash about to their hearts’ content and rest there, their naked figures glistening in the sunlight. On the ghat, reserved for the people from patidar, baniya, and brahmin castes, children would be rarely seen, accustomed as they were to bathing at home, pouring lota after lota of water, over their pure, pious heads. Only their womenfolk visited the ghat, with their daily washings and water-pots. Flaunting their symmetrical teeth, arranged like the row of pomegranate pips and sparkling nose rings, they would unleash the beauty of their silken blouses under a brilliant, golden sun.

At times, the pots slipped off their hands as they burnished or dipped them into the waters; at other times, their saris got lost. Bewildered, they would then plead with Amro, the king of the lake. “Bhai, please bring me my pot. Bhai, I cannot spot my sari. Please search it for me.” Amro would readily oblige and keep gazing at their happy fair faces, slim hands, tiny ears, symmetrical noses and sparkling necklaces. Of late, he had learned to admire the beauty of their lips and teeth as well.

Amro was famous in the village by the epithet “Crocodile of water.” When he was a child, his mother endlessly worried about him and his future; she would be heard ranting, “This bloody idiot does’t feel like coming out of water. Don’t know what’s the matter with him. Rascal will come back to his senses only when some enemy of his previous birth, a bloody croc, devours him one day!” No doubt, in his community, boys and girls learned to swim as naturally as they learned to walk; but Amro turned out to be an extremely precocious child, a star swimmer amongst them. To put it a bit hyperbolically, the water became his territory for charity, for performing acts of benevolence, such that would put every donor in the village, however great and influential, to shame. “Bloody koli has been acting so uppity these days. Did you notice that? Thrashing about in the lake all the time, what does he think of himself! He is a bloody angler after all, so he would do everything. What’s the big deal?” But to the children of these refined lot, Amro was nothing short of a superhero, an emblem of prowess.

Adept in a wide array of swimming styles and somersaults, he’d jump headfirst from the topmost branch of the bunyan tree to the fascination of his young audience and float up in the center of the lake; sometimes, he would take little children on joyride into the lake on his back. Occasionally, he would carry commuters piggyback to the other bank. While swimming at full throttle or floating supine with the ease of somebody lying on a cot, while slithering steadily across without causing the slightest ripple or soaking everybody by thrashing violently about, he would unfailingly pull a crowd of wonder-struck children, their eyes poppeout, minds boggled.

Moreover, he would herd out buffaloes and wayward bulls that often strayed deep into the lake and also groom the horses of the village overlords. But this very skill turned out to be the bane of his life. When he came of age, his father gave him away as a serf to a big Patel landlord to do sundry jobs like looking after the cattle, the cattle-shed and the farm. But the poor fellow couldn’t get the delight of the lake out of his mind. When he herded the bullocks to the lake, either to wash them or slake their thirst, he would while away hours together in the waters. He would set them free in the lake and then dive in to herd them out. No marks for guessing that he would drive the bullocks, not to the village bank, but to the opposite bank. The shortest possible route to this bank being that of water, he would once again shepherd the bullocks from that side to this. As soon as he came out, wrung his dhoti and tied the leash of the bullocks to the arching roots of the bunyan, people would plead with him for other trifling jobs. Willy-nilly, he would oblige, thus leaving his landlord waiting and seething for hours on end.

“What should I do with this foolish monkey?” the Patel would fret and fume helplessly, but he didn’t have the guts to try the most efficacious rural panacea on Amro, which was, a good deal of thrashing. Ultimately, he threw the croc out and so did Amro’s angry father. Heartbroken and hungry, he went over to the marbled ghat and sat there, downcast and distraught. Even during the brief while, he sat there, elderly people and passers-by severely reprimanded him for not observing village codes of propriety and public decency.

“Hey, how dare you buzz in here? Don’t you bloody know, this ghat is reserved for women from cultured families?”

As the high noon glared, Amro’s finely chiseled face shriveled. Even the middle-aged women on the ghat, to whom he was just a head that brought back pots and saris from the lake, began to squirm uncomfortably at the sight of such strapping young man. Tired of constant reproaches and angry glares, Amro jumped into the lake, swam to the opposite bank and went fast asleep under the bunyan tree.

Nobody knew what happened to him thereafter; in fact, nobody cared to know where the ghoul stayed or how he survived. But one sunny afternoon, people saw something like a long, large beam floating in the middle of the lake and with that, the word spread, “A crocodile has come to live in the lake.” Children on their way to and from school would stop at the lake for its glimpse and if something long and black caught their curious eyes, they would cry out in excitement, “Look… the crocodile…there!” Though nobody could confirm the existence of a croc with absolute certainty, stories set sail. “I had seen the croc, basking in the roots of the bunyan on that other ghat. God, it got the hell out of me!” Gradually, people even began to stumble into evidence, ingeniously marshalled to support the factuality of the narratives that hung over every crossroad and circle.

Meanwhile, one day the young daughter-in-law of Harji sheth slipped into the lake – nobody knew how – while she was washing clothes. The women on the ghat shuddered with horror. Everybody rushed home quickly finishing their chores. “O my mother, I’ve no doubt in my mind, it was a croc! Otherwise, if she had drowned, she would have come up to the surface at least once, wouldn’t she?” Harji sheth offered a bagful of gold to whoever took a plunge in the lake and salvage the body of his daughter-in-law, but to no avail. Nobody had the guts. Someone naughty from the crowd of onlookers taunted: “You see, even crocs have got clever these days. It carried away someone who had glutted on ghee and coconuts.” Jokes apart, at this moment of crisis, one uppermost on the mind of every villager was Amro. “If only Amro was here! He is so brave, he would have pulled her out of the mouth of the crocodile.” But where was he? Where on earth was Amro?

From that day on, nobody sat on the last step of the ghat for washing clothes. Women would fetch water to upper steps in bowls and pots and wash their clothes there. They would fill their pots standing cagily on the last step of the ghat and even if something like a coconut frond or broken earthen pot drifted near them, they would cry out in horror: “O dear me! Crocodile!” and their water-pots would slip from their hands. Nobody could muster courage to pick up the drifting pots even through they were within reach. Poor women would grumble, “If only Amro were present! That damned errant rascal. God knows where he has buzzed off!” Those waterpots would keep drifting in the middle of the lake, as if in dilemma as to whether to seize this opportunity to flee to the other bank and practice yoga in company of the bunyans there or to fall again in the hands of the women, the worldly trap of passions. And within a few days, those pots too would transform into crocodiles. Children would babble, “Today there were five crocodiles in the lake.” “Yes, yes a female croc also has come and is pregnant.”

Spooked by the rumors, people began to exercise great caution as they let their cattle drink from the lake. But it was very difficult to keep the cattle away from the lure of waters; bullocks and buffaloes hauled at their reins and chains and slipped into water at first opportunity as their owners kept helplessly gaping at them. If the cattle swam to the other bank and got out there, they offered a lamp of ghee and a coconut to Mother Ashapuri as per their vow. And if the cattle vanished in the middle of the lake, they went home in tearing distress, sighing in memory of Amro who always helped drive stray cattle out of the lake. “If only Amro was here!”

The hypothetical condition – “If only Amro was here!” – started echoing at every crossroad with increasing frequency. The village head invited experts to kill the crocodile; however, nobody’s art or craft worked. Amid such tizzy, one day the news spread in the village like wildfire. “The crocodile is killed!” “Where is it?” “How?” “Who did it?” Questions, unbelievingly asked, were answered with a plea to believe, to take a leap of faith. “On the small bank where it used to come out to have sun-bath.” “Did you really see it?” “Oh no, I haven’t been there, but I heard someone saying that he saw it with his own eyes. Somebody had ripped behemoth’s stomach apart. And the bloody dragon was lying with his mouth wide open.” And when people probed the actual witness for the source of news or any clinching evidence, he pointed out another witness. The fear of the crocodile had dug such deep roots in people’s minds that nobody was ready to go look at the croc’s carcass and confirm the welcome news. After a lot of discussion and tiring deliberations, a resolution of sorts was passed, the croc was no more. Period. But then, some people couldn’t do without throwing a spanner in the works; so, an old man deflated the jubilant mood by proclaiming with discreet maturity,

“Dear, forget the croc and suchlike; it’s all mumbo-jumbo. I mean, doesn’t the lake take a human sacrifice every year? I have been saying this so long; whatever you do, the lake is not going to leave us. This is an evil soil, do you understand?”

Deciding not to heed this untimely, spoilsport warning, people got on with their chores, relieved that a calamity had been averted. The next year passed uneventfully, without any major troubles, either as the croc was dead or because the pots and the cattle, in the habit of slipping from human hands, had decided not to abscond anymore.

And then the fateful thing happened; Madho’s wife slipped over the mossy steps, and almost drowned if it wasn’t for Amro who had materialized suddenly from somewhere, perhaps from thin air. She was brought home and laid down in a cot. People said, the woman had come back from the threshold of the graveyard; she was Holy Mother’s chosen one. Overpowered by a feeling of awe, mixed with a secret fear, everybody began to behave peculiarly with her, as though she had been transmuted overnight into a heavenly being. Madho himself began to hold her in great awe. In their bedroom, pitch-dark as night, she lay in one corner, flabby as a crumpled quilt, but Madho in his canopied cot couldn’t sleep a wink.

Uneasy days began to wear on. The happy tidings that “Amro has returned.” wafted across the village. “Make him the witch-doctor.” “Gratify Mother Ashapuri.” Proposals of different kinds and merit rolled in. In a not-to-be-missed spectacle, the entire village set out in search of Amro; the village head set out, the sheth set out, the sahukar set out, Madho’s father set out, even Amro’s father set out, but Amro, the good man, was nowhere to be found. Everybody began to ask around, “Hey, did anybody see Amro?” and everybody replied, “Nope, but somebody was saying that he was seen briefly in the lake the other day.” “Yes, in the evening when I herded my bullocks there, somebody was bobbing up and down in water near the small ghat.” “Yes, on the full-moon night, I saw a man taking a plunge into the lake from the bunyan top. Who else can it be, if not Amro?”

Meanwhile, another rumor began to do rounds in the village. “Amro has been touched by Mother. At the shrine of the Khatris – there, on the village outskirts, you see – he was heard telling the vaghari people that Holy Mother would speak, not to the village but to the lake. If anyone wants to request Mother or make an offering to her or place something at her feet, they should leave it at the village ghat, and Amro would carry the offering and prayers to the Mother.”

And in no time, the devout village folks began to line up. At dusk, someone or the other would prostrate before the lake and leave something, prasad or a gift, on the big ghat in the hope that Mother’s grace would protect them. In the thickening darkness, oil lamps burning in a row alongside the white of the sacrificial coconut, glimmering like the teeth of a heavenly fairy, presented a wonderful spectacle. Sometimes a small chunni too would glitter demurely through the shy, moonlit night.

The business of worship, with Amro as an intermediary, picked up faster than one had expected, but Amro, for one, never presented himself to the villagers in person. Many a time, a glistening head would be espied floating through the sheet of lake waters as far as the low ghat. At such moments, the spectators, though hard put to get a glimpse of the face, would jump up exclaiming, “Amro! Amro!” Besides, now suddenly, even stray cattle had begun to turn around from mid-lake as if driven back by an invisible cowherd. Copper and brass water-pots that sank in the previous day resurfaced the next morning. The village folk realized, this was Mother’s grace, being showered upon the village through Amro’s good offices.

No sooner than Amro’s divine connection had been put to rest than the whispers about Madho’s wife being blessed with Mother’s touch began to animate every nook and cranny of the village. “Holy Mother has blessed her. May Mother fulfill everybody’s wishes!” There wasn’t even an iota of suspicion about it, neither about the causes or chronology of events, oh no. Within no time, Patel’s house became a place of pilgrimage and visiting it a holy ritual. Sitting in a sprawling room, Amba, a long veil drawn over her head, would gently take her lotus-like, braceleted hand out of her crimson sari and place it on children’s heads who lined up with their mothers for her blessings. After the dusk, when the darkness shrouded the village, she would head for the lake, wrapped in a bright red sari, a brilliant pitcher on head. By chance, if somebody happened to be present there at that unearthly hour, he would instantly sneak away for the fear of crossing Mother’s path. People claiming to have witnessed this awe-inspiring scene with their own eyes, reported that her pitcher, brimming with water, came floating back to her straight from the middle of the lake. And the pleased Mother sometimes let out a ringing laughter.

With monsoon in bloom, the lake began to whelm at both banks. And the fear hibernating inside people’s hearts began to squirm. “Would the lake spare us this year?” Villagers became skeptical again. “O, hell with it. The Mother’s mercy will protect us.”

But how long would it take the eastern wind to turn into the western one? Not much. Loose tongues began to wag throughout the village. “Hey, did you see it?” “What?” A castle of curiously craned heads rose round the person asking the question.

“Last evening, Amba and Amro were sitting on the ghat close to each other.”

“Hey, will you believe?”

“What?”

“The other night, they were swimming in the lake.” A mix of amazement, hope and expectation washed over the women in the audience. “Wouldn’t the merciful Mother place her holy hand on my head?” a woman wondered. From then on, a huge variety of entreaties and requests began to be lodged with Amba. And Amba, giggling behind the veil, would reply, “I will try asking it to Mother.” As they conjured Amro’s image in their minds, the hearts of women, both young and old, surged with inscrutable emotions; in their racing hearts, they secretly coveted Amba’s fortune for themselves.

On the last day of Navaratra, Amba was busy blessing the thronging worshippers. The holy word had gone around, “Go and ask Amba for whatever you desire today, and Mother will grant your wish.” So, everybody had flocked to make a wish except for the person, who, sitting at the chotro, kept muttering to himself, “I know, nobody is going to listen to me. This evil soil is not going to rest without taking a life, whatever you do!”

With her lotus hand, Amba blessed everybody, the old and the young. People falling at her feet, though slightly frightened of her aura, would throw a fleeting glance from the corner of their eyes at her face covered by a long veil. Under the dim luster of the veil, Amba’s face sporting a gentle smile, flashing a slim row of sparkling teeth, looked ethereal and divine. “I have never seen Mother in such splendid elegance. What charming grace, O Mother!” the devotees exclaimed.

After playing the season’s last garba and ras, people went to sleep. There was no one in Amba’s room except for the lamps of ghee, placed near the ceremonial wheat grass and the row of earthen lamps, placed near the holy tridents painted on the eastern wall. The flames had been burning steadily.

Standing by the wall daubed crimson with the lamp light, Amba applied fragrant oil to her six-feet long hair and gathered them into a bun at the back of her head; then, she smeared a small, round, red bindi on her forehead, put on a skintight green silk blouse, pulled its tufted strings at the back and tied them into a knot. Wearing a brand-new sari, she kept looking admiringly at her image in the mirror. Under her sharp nose, adorned with a glinting nose-ring, her lips and milky white teeth wove together a disarming smile. Pulling the end of her new sari overhead, she set out for the ghat.

On the ninth day of lunar fortnight, the moon-god had halted for rest at the top of the shrine on the eastern ghat of the lake. Tired, as he threw a glance below, he froze with shock and surprise. Standing at the ghat, somebody was bathing in his raining white radiance. “Who can it be?” he wondered. Almost immediately, the guest looked at him and he was mesmerized. “God, people even more beautiful than me dwell on the earth.” words tripped off his mouth. Overcome with desire, he had hardly extended his snow-white hand to touch that fair face when, two hands like the hood of the great snake Shesha emerged from the lake waters, followed by a head like a full-blown blue lotus.

The woman standing on the ghat took off her sari and dropped it on the last step. Then, she went and lay down supine on those hoodlike hands. That blue lotus, those hoods and the supine figure lying atop- all the three began to skim into the lake as the moon gaped at this unusual voyage. Except for the slight rippling sound, the waters allowed them a right of passage, a safe passage. Gazing steadily at the blue lotus and the lotus covered by a green blouse, the heartbroken moon sank on the other side of the shrine.

Next morning, the morning of Dassehra, the first visitor to the village ghat was startled on seeing Amba’s brand new sari lying in a pile; the second was amazed; the third imagined something; the fourth investigated it; the fifth testified to its truth and the sixth broke it to the people on the ghat. ‘Amba!’, ‘Amba!’. “What happened to her?” “She is not at home. She is not anywhere.” “Is this surely her sari?” “Yes, it was bought from Harji sheth’s shop” “But where did she go?” and in answer to that question, people silently pointed their hands to the lake.

An unsavory thought wriggled in the minds of villagers, but nobody had the courage to voice it. Nobody wanted to speak anything about it. People accustomed to self-address mumbled: “One, who saved her, took her away. In short, it won’t be wrong to say that she had become his property right from the day he saved her.”

But the one person, who had been proclaiming his prophecy for years now, was not convinced. He followed his old line of defense, “You witnessed it, didn’t you? What have I been saying? The evil soil would not be appeased without taking its toll!” Deeming what he said as convenient and thus true, people dispersed, scratching their heads over whose turn it would be next year.

Looking like a vast platter full of milk, the lake, flanked on all sides by sprawling bunyan trees, remained glistening in the auspicious sunlight of the Dassehra. And the bright red sari, lying untouched on the last step of the ghat, kept giggling every now and then as if tickled by the white flowers printed on it. And with it giggled the all-knowing lake.

*******

‘Sundaram’ (Tribhuvandas Purushottamdas Luhar) (1908-1991 AD), the winner of prestigious awards like “Padmabhushana” (1985) and “Shri Narsinh Mehta Puraskāra” (1990), occupies a special and distinguished position in the gamut of Gujarati literature for multiplicity of reasons. In alliance with Umashankar Joshi, he set into motion what is called New Poetry in Gujarati literature. Sundaram enhanced the thematic range of Gujarati literature by exploring tabooed and unacknowledged issues and endowed it with attributes of radicalism and modernity. He ranks among the few early poets of Gandhian Era who creditably democratized the language of Gujarati poetry in addition to making it increasingly topical and relevant. Being a versatile artist, he made an enriching contribution to almost every genre available to a creative practitioner i.e. poetry, short fiction, drama, essay, reflective prose and travelogue. Further, he was a renowned critic and an inimitable translator. He rendered unforgettable service to Gujarat and Gujarati language by importing works from Sanskrit, and English by way of translation. In his growth as a writer, he was influenced by forces as diverse as Marxist, Gandhian and Aurobindonian. In the hey-day of his creativity, under Gandhian and Marxist influence, he produced poems and short stories with activist overtones voicing his disenchantment with the existing social system and power politics. The modern-day critics hail him as a precursor to Gujarati Dalit Literature. However, at an inexplicable turn of events in his life he came under the yogic and spiritual influence of Aurobindo and resorted to reclusive withdrawal from society and to some extent from his commitment to Gujarati literature by moving permanently to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry in 1945.

Hemang Ashwinkumar (1978-) is a poet, fiction writer, translator, editor and critic working in Gujarati and English. His works have appeared in journals and books of national and international repute. His book-length English translations include Poetic Refractions (2012), an anthology of contemporary Gujarati poetry and Thirsty Fish and other Stories (2013), an anthology of select stories by eminent Gujarati writer ‘Sundaram’ and Vultures (2022), a novel by Gujarati Dalit writer Dalpat Chauhan. His recent Gujarati translations - Arun Kolatkar’s Kala Ghoda Poems (2020), Sarpa Satra (2021) and Jejuri (2021) - have made a valuable, critical intervention in Gujarati literary sphere. His forthcoming books include Fear and Other Stories, a collection of Chauhan’s translated short fiction and Translating the Translated: Poetic and Politics of Literary Translation in India, a monograph on theory and practice of translation. His poems have been translated into Greek, Italian and other Indian languages

Leave a Reply