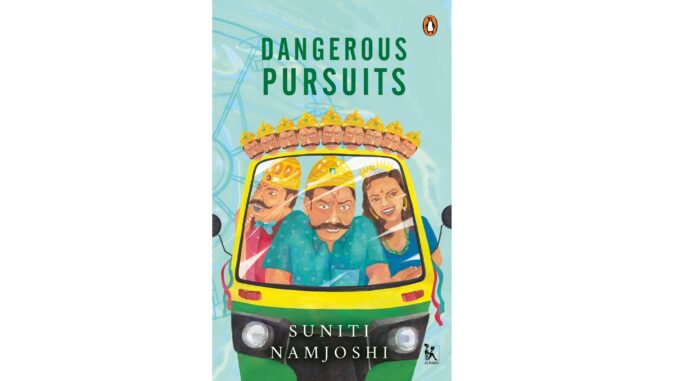

Dangerous Pursuits. By Suniti Namjoshi. Penguin Zubaan. March 2022. 240 pages.

Suhasini Vincent

I

n her preface to Dangerous Pursuits, Suniti Namjoshi warns readers that our reckless pursuit and addictive use of fossil fuels is a ‘dangerous’ one. She muses on how we will be perceived by our future generations. Will we write ourselves off as a failed society who let climate change lead us to a well-merited oblivion?

It’s unsettling to think that we are now on the verge of destroying ourselves and the planet because of our own efforts to make the world a comfortable place … there are massacres, world wars, genocides, floods, famines, plagues … We’ll have to change – our ideas, our attitudes, our very make-up. (Dangerous Pursuits 3-4)

Postcolonial writers like Amitav Ghosh, Arundhati Roy and Sudeep Sen have adopted an eco-critical sleight of hand to spark eco-critical awareness to the world at large. Amitav Ghosh in his work The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, wonders if the present generation is deranged! He warns readers that “this era, which so congratulates itself on its self-awareness, will come to be known as the time of the Great Derangement” (Ghosh 11). Similarly, Arundhati Roy cautions readers that we are engaged in a race toward extinction “as we lurch into the future, in this blitzkrieg of idiocy, Facebook ‘likes’, fascist marches, fake-news coups” (Roy 2). Likewise, Sudeep Sen poetically articulates the present-day situation as one where “we stare starkly at the climate change we’ve helped create” (Sen 33). We live in an ‘Endangered Earth’.[1] Like Ghosh, Roy and Sen, Suniti Namjoshi’s fables and stories in Dangerous Pursuits are another call to protect our planet, to distrust the grandeur of empty materialistic quests and to make a ‘material turn’. The term ‘material turn’ is used by Serenella Iovino in her work Material Ecocriticism in which she describes the existence of material forces and substances – the agency of things and their role in materialistic societies, and how narratives and stories contribute to make meaning out of the material world. She describes an enterprise of writing that is replete with “a material mesh of meanings, properties and processes, in which human and non-human players are interlocked in networks that produce undeniable signifying forces” (Iovino 1-2). Ghosh’s anthropological fiction, Sen’s poetry, Roy’s political essays and Namjoshi’s fables serve as new contemporary modes of thinking and imagination to signal the need to protect our ‘Endangered Earth’. In Dangerous Pursuits, Namjoshi’s short stories and fables insist on the need to make a ‘material turn’ and consider how materialistic activity in the name of progress affects human and non-human environments.

Namjoshi is the author of several collections of poems and fables as well as children’s books. These include – Feminist Fables (1981), The Conversations of Cow (1985), Aditi and the One-eyed Monkey (1986), The Blue Donkey Fables (1988), Saint Suniti and The Dragon (1993), Building Babel (1996), Goja: An Autobiographical Myth (2000), Suki (2013), The Boy and Dragon Stories (2017), and Foxy Aesop (2018). She worked in the Indian Administration Service before leaving to do a doctorate on Ezra Pound at McGill University in Canada. She now lives in the southwest of England. Her stories and fables figure Western and Eastern myths and fables; she configures the unstable, shape-shifting personae and plots of these myths in her narratives; and she reconfigures their moral lines and narratives to suit the context of her storylines.

Dangerous Pursuits bears a resemblance to a Greek-triptych work of art that is composed of three carved, folded panels hinged together. It comprises three sections that are variants of the theme of Climate Change: “Bad People”, “Heart’s Desire” and “The Dream Book”. In three dream sequences, the reader discovers a world that has gone wrong and must be set right. This idea of a topsy-turvy world is a recurring one in Namjoshi’s fictional space. It is interesting to refer to the Spindly Cow in Namjoshi’s The Conversations of Cow. Like Nut, the ‘Great Cow’, the sky goddess of Egyptian mythology, who swallowed the sun at dusk and gave birth to it anew at dawn, the Spindly Cow chomped and ingested the material world each day like “pots and pans, kettles and crayfish, cabbages and turnips, articles of clothing, houses and furniture – you know, just ordinary things one sees all the time” (Namjoshi, Conversations of Cow 80-1). Namjoshi, the fabulist resorts to chaotic verbiage by enumerating a list of opposing pairs comprising of kettles and crayfish, tigers and terrapins, to highlight the chaotic state of disorder in the cow’s interior. In the fable, the Spindly cow’s intake of buildings and factories, humans and animals, leads to a deplorable state when the Earth loses its form and resembles a pock-marked lump. Unable to consume more, the Cow burst and a chaotic world like the one we have today, spilled out of her. The fable’s closure endorses the new disordered creation as the dawn of a new world order “where the world carried on,” but in a different way (Namjoshi, Conversations of Cow 85).

The fable’s message is cautionary, reminding us of the need to protect our endangered planet and leave a more orderly world for our offspring. In “The Creation: Plan B”, a fable featuring a Parrot and a Tortoise, Namjoshi starkly reminds us that there is no Planet B for humans.

One day Parrot said to Tortoise, ‘I say, let’s make the world.’… For a moment or two they contemplated the world they had agreed upon. ‘I say,’ said the Tortoise, breaking the silence, ‘do we have to have people?’ ‘No,’ replied Parrot. ‘Phew,’ said Tortoise. And they lived happily ever after. (Namjoshi, The Blue Donkey Fables 21)

In the negotiation of a new world devoid of humans, the fable ends with the fairy tale closure: “they all lived happily ever after” (Namjoshi, The Blue Donkey Fables 21). By imagining a powerful ending where everlasting happiness exists ever after, Namjoshi foregrounds the idea of ‘eternal bliss’ in the animal world. But what about our world, our ‘Endangered Earth’?

In the first dream sequence of Dangerous Pursuits entitled “Bad People”, Namjoshi’s short story captures moments of historical upheaval, and moulds the shapeshifting, mythical configurations into a new reconfigured space in which the mythical characters are transformed. Namjoshi’s first-person narrator is Ravana, the demon-rakshasa king of Sri Lanka who unlike his Hindu-mythical-ten-headed-evil counterpart is engaged in a quest to save the planet. Along with his brother and sister, Kumbhkarna and Shurpanaka, the giant-trio awaken after an eon-long slumber to discover the 21st century. They ascertain a world run by very bad and evil people set on destroying the planet. Apt clippings from newspaper reports or transcripts head each section of “Bad People”.

‘Little, did we know we were running against some very, very bad and evil people …’

Transcript: Donald Trump Talks Impeachment Acquittal

In New Conference Speech, 6 February 2020

(Namjoshi, Dangerous Pursuits 9)

Through the satirical inclusion of a present-day press quote, Namjoshi depicts characters whose identities are shifting and multiple. Through the tool of masquerade, the trio siblings – Ravana, Kumbh and Shupi – don a variety of masks without necessarily concealing essential identities to confront the so-named bad people of the 21st century. Ravana’s masquerade to amuse himself, results in his “regeneration as an Epic Villain in modern times … the Ten-headed Demon, Scourge of the Universe, or, perhaps for a change, its Well-Meaning Saviour” (Namjoshi, Dangerous Pursuits 15). The villains and the antiheros in the epics come across as quite nice people in Namjoshi’s universe when compared to the triumphant Trump who was acquitted for incitement to insurrection of the White House by his republican-strong Senate. Each chapter of the story also has a fable to substantiate its opening-newspaper transcript. For instance, in the episode, “You are so bossy”, the CNN extract states:

Harry and Meghan say they’re “stepping back” from the royal family. The palace says it’s “complicated.”

- CNN, 9 January 2020, https//edition.cnn.com/2020/01/08/uk/harry-meghan-step-back-royal-family-gbr-intl/index.html. (Dangerous Pursuits 24)

In the Blue Donkey fable[2] that follows, a typical ‘beast-of-burden’ donkey yearns for a better life of lazy, indulgent living in green pastures. She was granted her wish, but after a leisurely life, she finds that her donkey grazing life is not quite what it seemed and realizes that “On earth, there is no earthly paradise …. We are donkeys and haven’t built it” (Dangerous Pursuits 31). The reference to the much-mediatised royal family rift, is to highlight the importance granted to the trivial when there are more pressing climate-related issues like famines or earthquakes or massacres that must hit the headlines. Ravana, in his new role as a citizen of the world, decides to draw up a plan for saving humanity. In a bespoke world of aspiring, billionaire-space cosmonauts, Bezos-Gates-Buffet-Musk-Ambani-Ma, the rakshasa trio realise that it is ‘money’ that makes the world go round as “Money breeds itself” (Dangerous Pursuits 49). The fable of the lonely giant who tilled the land, reaped a rich harvest, multiplied his gains until he possessed the whole world is typical of space-age billionaires of today, soon to be trillionaires, aiming to conquer terrestrial and planetary intergalactic space. The birth of a business empire requires the launching of a hot product, but the moral of the fable warns that “To make money in order to make more money doesn’t make sense” (Dangerous Pursuits 52). The shape-shifter entrepreneurs come up with a million-dollar idea of a Golden Balm for the human condition. With the help of grandma Ketumati’s balm, these bad people of an erstwhile epoch decide to outwit the bad people of present times. Patented and named after the Golden Isles off the Georgia Coast, the balm rendered people ‘fairer’ in both senses of the term, lightening skins, rendering justice, and transforming a person into a saner, kinder, and sweet-tempered individual who believed in protecting Mother Earth.

The eleven sub-sections of “Bad People” have fables and stories interwoven into the narratives. In the spinning of the tale, the story frame is like a ‘multi-layered box’ containing various “small Chinese-box worlds, arranged horizontally and vertically, where every compartment, no matter how small it is, coexists with every other compartment, retaining its separate identity (McHale 112). In Namjoshi’s fables of giants, sleeping giants like Ravana, the king of rakshasas, do not just lie lazily around, but walk away and think things through in dream sequences. In their quest for perfection, dreams of the characters though illusory get woven together. The protagonists can magically see each other’s dreams. The reader discovers hypodiegetic worlds or Chinese box worlds or babushka nestling dolls that fit into each other. Namjoshi’s tapestry has narratives interwoven into other narratives: the sleeping rakshasa Kumbhkarna, “is determined to be a citizen of the world and to make himself useful” (Dangerous Pursuits 49); giants wisely agree “that a great deal of money gives a great deal of power” (Dangerous Pursuits 51), but money is never shared as the adage goes that the rich remain rich and the poor are always poor; the rakshasa sister, Shurpanaka recites a poem on the color of sanity and the need for it in today’s world; and in the story of “The Undeserving Poor”, a poor girl and a ragged crow sell bits and pieces of themselves in the quest for fortune and console each other through story telling. In the fable of the hillside stone sisters, the sisters of flawless character, renowned for their miracles of merit, get transformed into stone to ensure that they remain etched in human memory. Thus, dream narratives of million-dollar ideas are juxtaposed with the burdens of being rich, generating intended confusion over where the boundaries lie, where one narrative stops and another begins, and reaches sometimes even into the level of the reader’s own lived narrative itself. It is interesting also to refer to Namjoshi’s The Conversations of Cow, where Bhadravati the Cow, voices the same idea.

Money is power. Money transforms … You can fly through the air. You can treat a supermarket like a giant treasure trove. You can have three wishes and a bit left over. You can, if you like, become invisible. You can buy life and time and energy. You can make people do what you want. (The Conversations of Cow 34-35)

In Postmodern Fiction, Brian McHale studies the “nesting” or “embedding” of a narrative from one ontology in the narrative of another ontology and he shows how this strategy can multiply worlds in a “recursive structure” (McHale 112). He explains that a story within the primary story projects a hypodiegetic world one level down where characters in the hypodiegetic world can enter another hypo-hypodiegetic world another level down, and so on ad infinitum. By weaving various yarns from the past, Namjoshi pulls the past into the present and the future into the past, incorporates “the theme of living life on the edge”,[3] draws the strands of fiction over the real and the real over fiction. The fabulist concocts stories to show that we live in a universe where different rules apply to each other, but all the different voices in the fictional space “entwine as though in an opera, and we become our own fable” (Dangerous Pursuits 106) in our quest to protect our ‘Endangered Earth’.

Ariel, a spirit controlled by the magician Prospero in Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, makes a genie-like appearance in Namjoshi’s short story, “Heart’s Desire”. Sycorax, an old witch who is only mentioned, but not seen in The Tempest, is the first-person narrator in the short story. Sycorax, the powerful witch-mother of the monster Caliban, who had imprisoned Ariel in a tree on a fictional Mediterranean island, decides to strike a bargain with the devil in this Namjoshiean tale. In a typical, Namjoshiean twist of events, an angel in the form of Ariel emerges in the tale instead of the much-awaited Faustian devil. Like Shakespeare’s Ariel[4] who is obliged to serve Prospero as a slave, Namjoshi’s Ariel pledges to serve her as a modern-day angel. Unlike Shakespeare’s Ariel who is bestowed with the ability to fly, become invisible, control the movements of people, and influence the weather and even trigger a tempest; Namjoshi’s Ariel has the capacity of engineering chance meetings and coordinating terrestrial happenings to please the human heart’s desire.

In a 21st century scenario where “Money is magic” (Dangerous Pursuits 112), Ariel’s offer of a Protection Plan includes paying money in the form of taxes, bribes, and levy in return for a peaceful, old life. As Sycorax evaluates her life plan, she wonders on how she can contribute her two cents towards saving the world.

Should she try to save the world? Make war on poverty? Prevent global warming? Redeem the species? The last thought makes her quail. It would be impressive. Is that what she would want? (Dangerous Pursuits 113)

Ariel steps into her role as PA or personal angel, an alien, and an all-purpose help capable of observing Sycorax’s inner turmoil of yearning to resurrect a wasted youth. As a literary angel who knows her literature, she dissuades Sycorax from contemplating a 20-year rejuvenation plan by referring to the Struldbruggs in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Ariel enlightens Sycorax on the evils of immortality. Sycorax discovers that that she has no wish to live like the immortal inhabitants of the fictional city of Luggnagg, who though born seemingly normal, continued to age physically and for eternity. Sycorax discovers that she has no interest in the material wealth of the universe, that is so evident in today’s societies of consumption; nor does she care for petty vanities of the latest fashions and brands. She deems that in a world that is ‘pernickety’, one tended to place too much emphasis on the trivial, trifling, frivolous or minor details. Could masquerading as Incognita or a so-called woman in disguise enable her to perform the worthwhile? Angel, Ariel’s personal PA, wisely responds that it is possible to be ubiquitous and omnipresent “in war zones and disaster areas, amid forest fires and cyclones, and, of course, in the regions where famine rules” (Dangerous Pursuits 138). This dangerous pursuit of being ‘worthwhile’ also figures in Namjoshi’s fable entitled “Broadcast Live”. It features the new incredible woman who despite her powerful personality voices the simple desire to live an ordinary life.

The Incredible woman raged through the skies, lassoed a planet, set it in orbit, rescued a starship, flattened a mountain, straightened a building, smiled at a child, caught a few thieves, all in one morning, and then, took a little time off to visit her psychiatrist, since she is at heart a really womanly woman and all she wants is a normal life. (Feminist Fables 63)

The fable breaks the very notion of the cultural stereotype of gender differences. The metaphors of impossible feats ranging from spatial adventures of lassoing a planet and reconfiguring its orbit, moulding, and reshaping the landscape, are juxtaposed with metaphors of feminine traits highlighting her need to remain a woman. Like the incredible woman in “Broadcast Live”, Sycorax voices the need to do something worthwhile. But her Faustian bargain to trade her soul for a normal life seems tragic and self-defeating as Sycorax realizes that she will be surrendering far more valuable than what may be attained. The tale offers new morals for the changing times, foregrounds the need to question, rethink and articulate new radical ideas. During her imaginary tryst with her friend Mme Friend, Sycorax understands that all human beings are like dying stars watching the news below that is “filled with deaths – calamities, accidents, wars” (Dangerous Pursuits 160).

You are the protagonist of your own story; but in the galactic scheme of things, you are of no more consequence than anyone else … Look at the jumbled junk heap that is your memory, and at the imperfect systems – your circulation, your nerves, your digestion – that keep you going, and accept that’s how it is. That painted paradise you want can only be as good as your imaginings”. (Dangerous Pursuits 160)

Through this dream sequence, reality and identity are rearranged in “Heart’s Desire to suggest life’s possibilities. The reader understands that in the inter-galactic scheme of things, every single attempt at protecting the planet matters. While reshaping and reinventing a new tale of a Faustus bargain, Namjoshi stresses on the point that feminist art needs new forms for women to find their place in the vast scheme of things on our ‘Endangered Planet’. Namjoshi figures the lively, spirit Ariel and the witch Sycorax from Shakespeare’s plays as 21st century characters engaged in a lively quest for climate change. She configures the idea of a Faustus bargain from 16th century German legends of Johann Georg Faust with Sycorax willing to sacrifice her soul for knowledge on how to do good to the planet. She reconfigures the tale as a dream sequence where Sycorax manages to ultimately challenge the existing status quo of a global crisis with a strong pledge – “I challenge you – with my wit, with my weapons, with my strength, with my bare fists” (Dangerous Pursuits 171)!

Namjoshi uses the stage of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in the final short story “The Dream Book”. The reader discovers a Namjoshiean recast of characters through dreams that are propelled by Ariel, the omniscient spirit-narrator. Ariel has the task of making people’s dreams come true. In this remake, Ferdinand, the Lord of the Island, prefers the chase of courtship to the romance; Caliban, the monster, and Prince Ferdinand discover that they are brothers engaged in different dangerous pursuits for power; Ariel and Caliban long for freedom from enchantment and spells; Miranda writes poetry voicing the fears of nature where trees, birds and animals, the so-called ‘nonentities’ on the planet are plunged in a vicious circle of nightmares in which they are constantly crushed and destroyed ; Prospero has the mage’s privilege of calling all the shots and unstitching time to fit the moment; Sycorax swims in a confused abyss of old-age memories that elude recognition. As a fabulist, Namjoshi excels in scrambling our awareness of Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest. Through a world of compromises, incongruities, ambiguities and distortions, the alert reader discovers a universe replete with nuances of imperfection, a fact that believers in scripture deny and oppose. Each character tries to interpret the dreams of others and discovers that “dreams are fragile and easily shattered” (Dangerous Pursuits 190). In a mode vaguely resembling one of magical realism, the dubious reality of a world that needs to be patched up is revealed through dreams, rumors and gossip between the protagonists. Namjoshi reworks Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, in which Malvolio’s daydreams make a surprise appearance and visit.

Malvolio on his daybed was once such a one.

His dreams were overhead.

It was unadvised. (Dangerous Pursuits 202)

She juxtaposes daydreams of Malvolio for wealth and riches with the hallucinations of Sycorax for a fair world where all species are treated alike. Namjoshi, resorts to self-conscious authorial intrusions to blur the distinction between story and reality. The intentional reference to Malvolio aims to highlight the contrast between a quest for the material world and an elusive dream to lead a better life. Caliban, Miranda, Prospero, and the rest of the protagonists from the Shakespearean pages find that their dreams clash, mingle, intertwine, and lie as “pretty and pitiless as glass shards” (Dangerous Pursuits 202). Yet, each time they dream time and time again about creating a better world and engaging once again in the dangerous pursuit of survival. In the final scene, the protagonists get together to embrace the notion of a collective effort.

Gonzalo: We’re creatures of time.

Miranda (rapping): We eat time.

Ferdie: Secrete time.

Cal: Creep, crawl and fly through time.

Miranda: And in our dreams we flounder in time.

Ferdie: Yes, wallow in time. Shall we consent?

Miranda and Cal: Yes.

Ariel: Consent to what?

Cal: To dream a better and kinder dream.

Gonzalo: Because others have done it?

Miranda: Yes. Those are pearls that were their eyes! (Dangerous Pursuits 228-29)

By casting her Shakespearean protagonists in their role as creatures of time, Namjoshi embraces the notion that literature is a created work and not bound by notions of mimesis and verisimilitude. Aesop in Namjoshi’s Foxy Aesop says, “Each time a story is told it means something different” (76). Similarly, Suniti says to her friends in Saint Suniti and the Dragon, “Poetry is the sound of the human animal” (29). Even though, the “Dreams are like poetry … (and) make no difference” (Dangerous Pursuits 208), words trigger poems. Namjoshi attempts to create fables, poetry and literature that make a difference to this world. In “The Kingfisher” she compares her craft as a fabulist to that of the kingfisher: “Fish, are like poems, you catch them when they leap” (Namjoshi, Blue and Other Stories 23). In the fable entitled “Dear Reader”, Namjoshi includes the reader too in her fictional enterprise of catching fables: “We are not fighters, but fellow-travellers” (Blue Donkey 51). Unlike the critic who fails to see the inner meaning of the creative fables, the reader is portrayed as one who accepts the fabulist’s world albeit the fictional incongruities, riddles, and enigmas.

The colour of my sun happens to be yellow.

Yours too, you say? I feel so pleased. Our task is

made easier. (Blue Donkey 51)

The idea of sharing similar views is pictured through the idea of drawing warmth from the same ‘yellow’ sun. In my first interview in 2006 with Namjoshi during her stay in Paris, she admits: “However hard the writer tries to write her poem as accurately as possible – with all the instructions put in (implicitly) about which associations are to be used, which not, and how it is to be read and how the tone changes – she (the writer) is nevertheless dependent on what the reader brings to the poem” (Vincent, Experimental Writing within the Postcolonial Framework, Appendix 1: 508).

Post colonial writers write of that sacred place in which writers revel in creative enterprise. Salman Rushdie, for instance, writes of this unassuming little room of literature tucked away in a corner of the large rambling house of world activity where the room is alive with “voices talking about everything in every possible way” (Rushdie 429). Sudeep Sen’s poetry also inhibits a similar “precious zone for philosophical and creative thinking, a space for silence and stillness” (Sen 160). Namjoshi calls this rich space of literary activity as, the “lost storehouse” (Dangerious Pursuits 202) of dreams, a privileged sphere of creative enterprise, from where the fabulist-writer can find inspiration for patching up our Endangered Earth. By daring to enter into the lost storehouse of dreams, the reader awakens stories waiting to be rediscovered and recast anew. Namjoshi’s Dangerous Pursuits is typical of postcolonial ecology where the mode of the fable serves as a new means for stimulating social action. Her fiction, thus offers new morals for the changing times, foregrounds the need to question, rethink and articulate new radical ideas.

Namjoshi’s sleight of hand is typical of how postcolonial writers, as new retellers of old tales, renew the spirit of Eastern and Western culture, revitalize language, revive literature and retill the ground for the ensuing reconfiguration of the fictional landscape. In Dangerous Pursuits, the reader sees how the postcolonial novel comes alive, as figures of speech mutate into figures of strength having the power to communicate and express new ideas. Namjoshi revels in flaunting how fiction has a greater purpose of revealing new vistas, mapping out a different way of tackling contemporary environmental problems of climate change

***

Notes [1] My use of the term the ‘Endangered Earth’ draws inspiration from the Jan 2, 1989, Time Magazine issue cover page that bears the image of the planet Earth fettered in twine with a dark crepuscular sun in its background. Instead of choosing a ‘Man of the Year’ for its cover, Time Magazine chose the title ‘Planet of the Year: Endangered Earth’. [2] The Blue Donkey is the narrator and the main protagonist in Namjoshi’s collection of fables The Blue Donkey Fables. The tales, fables and stories abound in allusions to the imperfections of our word and satirize human shortcomings. The Blue Donkey makes a guest appearance in Dangerous Pursuits. [3] Refer to my “Conversation with Suniti Namjoshi” in Weber – The Contemporary West, Volume 36: Fall 2019, p. 32-39 on ‘living life on the edge’. [4] The part of Ariel, the spirit, was played by women in Shakespeare’s plays until 1930. After this date, this part was played by both men and women. In Namjoshi’s short story, Ariel is cast as a she-angel.

Works Cited Iovino, Serenella et al. Material Ecocriticism: Bloomington; Indiana University Press, 2014. McHale, Brian. Postmodernist Fiction. London, Routledge, 1987. Namjoshi, Suniti. Feminist Fables. London: Virago, 1981. ---. The Conversations of Cow. London: Women’s Press, 1985. ---. The Blue Donkey Fables. London: Women’s Press, 1988. ---. Saint Suniti and The Dragon. London: Virago, 1994. ---. Blue and Other Stories. Chenna: Tulika, 2012. ---. Foxy Aesop: On the Edge. New Delhi, Zubaan 2018. ---. Dangerous Pursuits. New Delhi: Zubaan/Penguin, 2022. Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism, 1981-1991. 1991. Reprint, London: Granta/Penguin, 1992. Sen, Sudeep. Anthropocene: Climate Change, Contagion, Consolation. London: Pippa Rann Books & Media, 2021. Vincent, Suhasini. Experimental Writing in the Postcolonial Framework, Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012. ---. “‘Poetry is the Sound of the Human Animal’ - A Conversation with Suniti Namjoshi”, Weber – The Contemporary West, Volume 36: Fall 2019, p. 32-39.

******

Suhasini Vincent She is at present an Associate Professor (Maître de conferences) at the University of Paris 2 – Panthéon Assas since 2007 and lives in Reims, France. Her research focusses on the legal scope of environmental laws in postcolonial countries and explores eco-critical activism in the essays and literary works of Arundhati Roy, Amitav Ghosh, Sudeep Sen, Suniti Namjoshi and Yann Martel. Her research interests include the postcolonial dynamics of translation. She has interviewed authors like Suniti Namjoshi, Namita Gokhale, Ambai, Sivasankari, and other well-known translators and editors in the Indian literary scene.

Leave a Reply