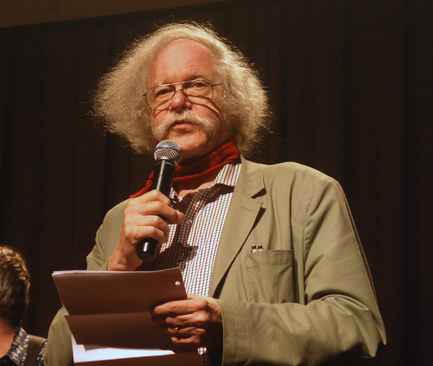

Ed: Sanders reading at the House Divided poetry event, Cooper Union, April 2017: Courtesy: Wikipedia

Jennie Skerl

T

he Beat Generation was a multi-generational movement that continued to have an impact on American arts and culture well after the friendship of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs that began it all in the 1940’s and well after the legendary poetry reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco in 1955. The Beat influence is still felt in contemporary slam poetry, performance poetry, and the testimonials of actors, film makers, and musicians. The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetry at Naropa University, founded by Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman in 1974, carries on the Beat legacy, introducing students to a broad range of “outrider” poets. An exemplary artist who has carried on the Beat message from the 1960’s to the present day is Ed Sanders, who has often been called a second-generation Beat. As a self-identified “beatnik,” Sanders played a central role in the early sixties avant-garde that led to postmodernist aesthetics and, at the same time, he was politically active in the peace movement that flourished during that decade. Later in his career, he memorialized the sixties in a four-volume collection of short stories, Tales of Beatnik Glory, completed over a thirty-year period (published in installments in 1975, 1990, and 2004), and in a book-length poem, 1968, A History in Verse (published 1997), which employed a poetics he calls “investigative poetry” to tell the story of that tumultuous year in American history. Thus, Sanders’ career directly links the Beats, the sixties cultural revolution, and postmodernism.

Part 1:

“Come, O 60’s . . . come and take us on thy thrilling ride.” (From Tales of Beatnik Glory)

Ed Sanders’ multifaceted artistic career began when he read Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” as a high school student in Kansas City, Missouri. Inspired by Ginsberg’s poetry and his powerful dissenting voice, Sanders hitchhiked to New York in 1958 to enroll at New York University and become part of the Beat poetry movement. Sanders soon became enmeshed in the Lower East Side poetry and arts scene—a distinctive avant-garde of the early sixties peopled by second-generation Beat, New York School, and Black Mountain poets who read in coffee houses, painters who founded cooperative galleries, underground film makers, and performance artists who created Off-Off Broadway shows and new art forms such as the happening. Some noted artists who were part of the community are Andy Warhol, Jonas Mekas, Sam Shepard, Julian Beck and Judith Malina, Diane di Prima, Joyce Johnson, Rochelle Owens, and Ted Berrigan. From the late fifties until the mid-sixties, the Lower East Side became an epicenter of artistic ferment, and Ed Sanders was in the midst of it all.

The Lower East Side arts/bohemian community was aware of the older Beats and earlier avant-gardes and built on their achievements, but they also introduced new ideas and a new artistic style that signaled what Marianne DeKoven has called emergent postmodernism. Perhaps the most prominent characteristic of this avant-garde was the democratization of the arts. Artists sought to create accessibility through low-cost materials or performances and an ethic of equality among artists and between artists and their audience. Democratization supported a drive toward eliminating hierarchies, both aesthetic and social. The combination of materials from popular, mass culture along with the traditions of high culture—including the classics—were part of this style, as was incorporating taboo subject matter and language, especially references to the body, sexuality, and drugs. Media and genre boundaries were also broken down by Lower East Side artists in an interdisciplinary style that combined word and image, sound and performance, and communal interaction among artists across media. Stylistically, erasure of boundaries was conducted in a spirit of play and spontaneity; thus, the division between work and play was also challenged. Sanders captures the principle in this

passage from Tales of Beatnik Glory: “… it was the best of times, it was the worst of times, but it was our times, and we owned them with our youth, our energy, our good will, our edginess. So let’s party. . . . Poetry was a party. Work was a party. When I put out an issue of F*** You/A Magazine of the Arts … that was a party.” Fugs rehearsals were a party. Even demonstrations and long meetings planning the revolution.”

Physicality, the body as the focus of art, was also a mark of this avant-garde, especially its emphasis on the sexual body as the ground of a new aesthetic and an imagined social utopia. There was sexual activity in underground films, nudity on the stage, explicit references to the body and formerly taboo language in poetry. Nudity and sexuality in the performing arts presented the shameless sexual body as a force for liberation. The bohemian community viewed sexual liberation, transgressive art, and free speech as linked projects that challenged conventional mores and censorship.

This same bohemian community was also the home of many political activists in the anti-nuclear, anti-war, and civil rights movements which in the sixties were linked to movements for free speech, sexual liberation, and the legalization of marijuana. The political and artistic were intertwined in that many artists were also politically active or contributed their art to benefit political causes. Indeed, it is the mark of this early sixties generation that political protest was integrated into their art—in contrast to the comparative withdrawal of the earlier generation of Beats and other bohemians in the late forties and early fifties. Group activity in politics and art fostered a strong sense of community, and the fusion of the aesthetic and the political created a utopian belief in the power of the avant-garde to change society by creating an alternative model. Sanders expressed this ideal as “Goof City,” a concept introduced in his first published poem, “Poem from Jail,” and described in Tales of Beatnik Glory as “a place of great freedom, affordability, cheap rents, adequate wages, wild times, plenty of leisure, guaranteed access to thrills and art, with streets so safe a person, man or woman, could walk naked at 4 a.m. and not be bothered or touched.”

No other artist of that time and place better exemplifies the sixties Lower East Side avant-garde than Ed Sanders: poet, publisher, musician, peace and free speech activist. His art was inseparable from his politics and was a form of both protest and changing consciousness. Sanders’ style in poetry, prose, and music employed the breakdown of hierarchies typical of arts of the period and was very much a part of the avant-garde program of democratization and accessibility. His work playfully combined elements from popular culture (such as cartoons, rock and roll, stand-up comedy), avant-garde art (such as open poetic forms, happenings, and mixed media), and the poetic tradition of the lyric going back to the ancient Greeks, producing an idiosyncratic collage of high and low culture, an inter-art mix of verbal and visual elements, accessible language, and his own characteristic humor made up of comic hyperbole, satire, slang, and neologisms. The sexual body as the site of cultural struggle was prominent in Sanders’ work, as displayed in some of his early poems, the title of his poetry magazine, and the sexual comedy of the Fugs (his folk-rock band). At the same time, ancient Greek literature informed his writing and music: during this time, he was also studying the classics at New York University, completing a degree in Greek in 1964. In addition, he studied ancient Egypt and learned to read hieroglyphics, which also entered his work.

In spite of his multifarious activities across genres and art forms, Sanders saw himself as a poet (as he is primarily known today), and especially as a performance poet, one of the dominant modes of postmodern poetry. Poetry readings were central to the Beat aesthetic which continues to influence performance poetry and poetry slams to this day. Early on, Sanders was a participant in coffee house poetry readings, entering the world of Beat-inspired public poetry events and honing his craft in Lower East Side venues such as the Cafe Le Metro, the Five Spot, and the New York Poets Theatre. He was associated with the St. Mark’s Poetry Project from its founding in 1966, which became a center of anti-war resistance as well as poetry. The young Sanders also educated himself in contemporary avant-garde poetry through his magazine and bookstore, placing himself in the context of Donald Allen’s New American Poetry, choosing Ginsberg and Olson as his mentors, and also adopting their chosen forerunners, William Blake and Ezra Pound. Ginsberg and Olson led poetry movements that resisted mainstream ideology and promoted experimentation with form—both traits which define Sanders poetry. The erudition of Pound, Olson, and Ginsberg appears in Sanders poetry also in his allusions to ancient Greek and Egyptian texts and myths.

Sanders’ first published poem (and the first that he considered worthy of publication) was “Poem from Jail” (1963). It was introduced by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Press, giving him recognition from the most famous publisher of Beat poetry, and officially established Sanders as a younger poet in the Beat movement. The poem, as in much of Sanders’ art, brings together artistic experimentation with his political commitments and real-life activism: it was written while Sanders served a sentence in Connecticut for protesting nuclear submarines by attempting to interfere with the launch at the New London naval base as part of a demonstration organized by the pacifist Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA). The poem’s visionary intensity shows the influence of “Howl,” but the form is Sanders own: short lines with a pounding rhythm based on Greek meters, overt political protest against nuclear weapons and war, ancient Greek and Egyptian myths combined with Christian references providing a structure for a spiritual journey, and the ideal of Goof City, “where every choice is allowed.”

In addition to his early visionary/political poems, Sanders was known for his explicit, often comic, poems about sexuality, which appeared in King Lord/Queen Freak (1964), The Toe Queen Poems (1964), and Peace Eye (1965). These poems are part of Sanders sexual liberation and free speech agendas, but they also make a serious argument about human sexuality as part of the natural world and connected to a divine life force as conveyed in ancient mythologies. A good example is “Holy Was Demeter Walking the Corn Furrow” (published date), a tour de force that imagines sex between a human (the poet himself) and a goddess, inspired by the myth about Demeter and Iasion. This poem is an early move into the narrative mode that is prominent in Sanders later poetry and convincingly portrays intercourse with a goddess who is also dirt and corn sprouts, silk, sheaves, and husks—an experience both literally dirty and ineffable. From these beginnings, Sanders developed his own idiosyncratic voice and a flexible style that could be visionary, transgressive, colloquial, humorous, narrative, or lyrical.

From 1962 to 1965, Sanders was also an influential promoter and disseminator of avant-garde poetry through his self-published poetry magazine, F*** You/A Magazine of the Arts, part of what Sanders called the mimeograph revolution. Sanders personally typed, duplicated, and stapled thirteen issues of his magazine. He stenciled the covers, which introduced the contents of the issues amongst a collage of Egyptian hieroglyphics combined with graffiti-like or cartoon images of penises, copulation, peace symbols, the eye of Horus (which Sanders called the Peace Eye), hypodermic needles, mimeo machines, and other images of both Sanders’ art and the bohemian scene. Sanders saw his word-and-image format as carrying on the tradition of Blake. This “do it yourself” magazine published many of the most prominent Beat and other avant-garde poets of the period: Carol Bergé, Ted Berrigan, Paul Blackburn, Gregory Corso, Elise Cowen, Diane Di Prima, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Le Roi Jones, Lenore Kandel, Denise Levertov, Michael McClure, Frank O’Hara, Charles Olson, Joel Oppenheimer, Gary Snyder, John Weiners, and more. The magazine also served as a manifesto for pacifism, free speech, sexual liberation, and the legalization of marijuana. The first issue announced a publication dedicated to “pacifism, unilateral disarmament, national defense thru [sic] nonviolent resistance, multilateral indiscriminate a pertual conjugation, anarchism, world federalism, civil disobedience, obstructers and submarine boarders, and all those groped by J. Edgar Hoover in the silent halls of Congress.” Seeking submissions, Sanders proclaimed, “I’ll print anything,” and writers responded.

In 1964, Sanders opened the Peace Eye Bookstore, which sold small press poetry publications and provided a base for Sanders diverse activities—the press, poetry, art shows, rehearsal space for his rock band, work on his experimental films, and political organizing. Peace Eye was a gathering place (called a “scrounge lounge” by Sanders) that drew visitors from out of town as well as from the local community. The bookstore was raided by police in 1966 and Sanders was charged with obscenity based on issues of F*** You. Charges were dismissed in 1967, but Sanders was advised by his ACLU lawyers to cease publication. Thus, Sanders, like many other writers (especially Beat writers) and artists who were pushing boundaries at the time, became the target of official censorship and part of the fight against it.

The culmination of Sanders’ border-crossing and communal art during the sixties was his band, the Fugs, cofounded with another bohemian poet, Tuli Kupferberg. The Fugs had a cult following and issued six albums between 1965 and 1969. The group was named after the euphemism that Norman Mailer was forced to use in his World War II novel, The Naked and the Dead, flaunting the unspoken obscenity and the censorship that the band defied. Writing their own songs, the Fugs combined music with poetry, political protest, social satire, sex comedy, and an anarchic style that usually ended performances with a Dionysian kind of happening, with Sanders, in his own words, playing the role of “a modern-day American Bacchus.” During the Vietnam war, they sang popular anti-war songs such as “Kill for Peace.” The Fugs also set to music poetry by Blake, Swinburne, Auden, and Ginsberg, among others. Musically, the Fugs were influenced by the popular music of their time—folk, rock, jazz, civil rights songs, as well as the avant-garde experiments of the Dada movement and contemporary performance art. Their eclecticism, erasure of genre hierarchies, and inter-art mix epitomized the art style of the sixties Lower East Side.

The Fugs also had a political role beyond protest songs, often playing to benefit the anti-Vietnam War movement or activists who had been arrested. Perhaps their most famous performance/protest was their exorcism of the Pentagon during the 1967 anti-war march in Washington, D.C., included in Mailer’s account of the event in Armies of the Night (1968). In 1968, Sanders, with anti-war activists and Yippie movement founders Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, organized a rock festival called the “Festival of Life” to take place in Chicago during the Democratic National Party Convention as a counter-cultural demonstration against the war in Vietnam. Another antiwar activist coalition, the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, planned demonstrations at the same time. The Chicago police force violently broke up these gatherings, and several organizers were put on trial for conspiracy to cause civil disruption. Sanders was not charged but was called to testify for the defense in 1969. There have been four movies made about the widely publicized trial, most recently the 2020 Netflix movie, The Trial of the Chicago 7.

At the end of the sixties, the Fugs disbanded, and Sanders’ life and work took a turn when he decided to investigate the Manson Family murders, which fascinated and horrified the nation. In 1970, he went to California to report on the case for the Los Angeles Free Press and with a book contract. Initially, in the media, the Manson group appeared to some to be a kind of hippie commune, and Sanders wondered if the hippie values of individual freedom, free sex, drug trips, and questioning authority had somehow led to a grotesque murder cult. Ultimately, he discovered that the Family was a group of young people who had lost their moral compass by turning over their lives to a manipulative lifetime criminal who claimed absolute authority over his followers. To Sanders, the murders illustrated the existence of evil in the world and the necessity of maintaining independence from authoritarian leaders. His book, The Family: The Story of Charles Manson’s Dune Buggy Attack Battalion, is generally regarded as one of the best books on the Manson Family murders and has gone through three editions with additions and updates (1971, 1990, 2002). Quentin Tarantino’s film, Once Upon a Time in . . . Hollywood (2019) brought renewed interest in the crimes and Sanders’ book.

A few years after publishing the Manson book, Sanders and his family settled in Woodstock, New York, where he continued to work as a poet, novelist, short story writer, activist, journalist, and musician–and he continued to be an innovator. He became well-known as a performance poet who accompanied his readings with music on his invented electronic instruments. Beginning in the 1970’s, Sanders’ writing moved into two new directions that employed narrative: book-length historical poems and a series of linked short stories which historicized the sixties avant-garde.

Part 2:

“The whole world is watching.” (heard on national television in 1968)

The experience as an investigator, researcher, and manager of a massive amount of data when writing about the Manson family, led Sanders to develop a new poetics, which he defined in his prose manifesto, Investigative Poetry (1976), and its counterpart in verse, The Z-D Generation (1981). The manifesto was also influenced by the public revelations in the 1970’s of government malfeasance, such as the Pentagon Papers, Watergate, the CIA’s secret experiments with mind control and participation in the drug trade, and the FBI’s counterintelligence program which illegally surveilled and disrupted political organizations connected to the civil rights, anti-war, and Black Panther movements. Sanders realized that he could use his research skills in developing a new kind of poetry. He conceived of investigative poetry as devoted to history and politics, supported by scholarly research and data-gathering, and presented in modern poetic forms that can also include new technologies and performance. The poet as investigator, historian, and story-teller performs the ancient role of bard, the chronicler of a civilization. Citing Blake, Pound, Olson, and Ginsberg as forerunners, Sanders takes courage from Ginsberg’s line: “Now is the time for prophecy without death as a consequence” (Death to Van Gogh’s Ear).

Investigative Poetry provides almost a blueprint for Sanders’ subsequent development of long narrative poems and ultimately book-length biographical and historical poems, his invented microtonal instruments, and his performance poetry. He moved away from Ginsberg’s rhetorical style to Olson’s concept of the poem as an open field and towards the poem that includes history proposed by Pound and Olson. He began working on long narrative poems about admired artists or activists and which also investigated anti-democratic forces in the United States. Sanders’ narrative verse books include Chekhov, A Biography in Verse (1995), 1968, A History in Verse (1997), The Poetry and life of Allen Ginsberg (2000), A Life of Olson (2018), and his longest poem: America: A History in Verse (five volumes on the twentieth century published 2000-2009, followed by four more volumes on the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, as yet unpublished).

In 1968, A History in Verse, Sanders skillfully employs the techniques of investigative poetry to revisit a year that may have marked the turning point in the public’s support for the Vietnam war (the year of the Tet offensive and the My Lai massacre). The political future of the United States was unalterably changed that year by the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy, President Johnson’s decision not to run for President again, and the turmoil surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. It was also a year of dramatic conflict between youthful protesters and the authorities in the United States and other parts of the world. By 1968, Sanders had been prominent in the New York avant-garde arts scene, the leader of a rock band, and an activist in the anti-war movement for many years. He was one of the Yippies that planned the “Festival of Life,” the counter-cultural response to the Democratic Party Convention which nominated Hubert Humphrey on a platform to continue the war. Thus, Sanders was a participant, witness, and later chronicler of what happened in his book published 29 years later. As he stated in the introductory note to 1968:

…I strutted through the time-track

Daring to be a part

Of the history

Of the era…

Sanders’ 1968 surveys the entire year in a chronological narrative, or what he calls a “chrono-flow,” that climaxes in Chicago in August of that year. The reader is educated in the politics of the war in Vietnam, the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, the Black Power movement, and the role of the arts in protesting the war. What happened in Chicago is placed within the broader cultural context of the 1960’s and also the personal context of Sanders life that year, his “time-track.” Furthermore, the history is told in poetic form, an epic in the modernist tradition of Sanders’ mentor Charles Olson, employing a montage of fragments while maintaining an accessible, overarching month-by-month narrative structure and a postmodern mix of historical, autobiographical, narrative, dramatic, documentary, prosy, lyrical, and visual elements.

The main story lines are the conduct of the war, the presidential race within the Democratic party, and the anti-war movement. Sanders describes U. S. government plots to suppress or disrupt opposition to the war carried out by the FBI, CIA, and ASA (Army Security Agency). These are linked to the FBI’s attempts to disrupt the civil rights movement and the Black Panthers, and to Sanders’ theories about government agencies’ involvement in the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy. Historical information about the foregoing, based on research, is complemented by information based on Sanders personal experience as a Yippie, musician, and poet. The story of the Yippies’ founding, their guerrilla theater tactics, and the planning for the Festival of Life in Chicago functions as a counter-cultural parallel to mainstream politics. As a leader of the satirical folk-rock band, the Fugs, Sanders is able to weave the popular music world into the narrative. Rock and folk music provided the sound track to the cultural and political revolt of the time and inspired a generation. As a poet, Sanders is able to draw the poetry community into the story, emphasizing prominent poets who spoke out against the war and refused awards in protest. Some extended episodes describe mass protests in other countries that reflect a world-wide cultural/political rebellion: Czechoslovakia, France, Mexico.

The various narratives converge in the events in Chicago on August 25-28, 1968. Here, Sanders gives a day-by-day account of how a free concert and initially peaceful protests were overwhelmed by violence when police attacked demonstrators and journalists in what was later called a “police riot.” The violence in the streets entered the Democratic party’s convention when police pushed protesters through the Hilton hotel’s ground-level glass window, when tear gas penetrated delegates’ hotel rooms, when Presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy set up a first-aid station in his suite, and when a well-known television reporter was punched by a security guard on the convention floor—all shown or reported on television. These officially recorded events are retold along with Sanders’ personal experience of chaos, fear, and horror in the parks and streets of Chicago every evening as the police violently drove people from city parks because the mayor’s office had denied permits to stay overnight. Yippie and other protest leaders attempted to calm the crowds and guide them to safety out of the parks. Daily conflicts with the police culminated on August 28 when the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam attempted to lead a peaceful march to the convention, resulting in an orgy of police brutality near the Hilton Hotel. A stunned television audience watched police clubbing, tear gassing, dragging, and throwing demonstrators who sat in the street chanting, “The whole world is watching.”

Part 3:

“We want to change the world without shedding a drop of blood.” (from Tales of Beatnik Glory)

Also, in the 1970s, Sanders wrote volume 1 of Tales of Beatnik Glory, which became a thirty-year project, resulting in four volumes of interconnected short stories. In the introduction, Sanders says he began writing the stories as a form of healing after his immersion in the Manson case. Tales is a fictionalized memoir chronicling the Beat and subsequent hippie counterculture of the Lower East Side from 1957 to New Year’s Eve 1970. Structurally, the stories proceed chronologically with a few exceptions for flashbacks and glimpses of the future. Sanders creates a numerous cast of bohemian characters: writers, painters, dancers, performance artists, musicians, filmmakers, political activists in peace, civil rights, and anti-war movements of the era. The imaginary characters interact with real people and respond to major historical events, such as the Great March on Washington, the peace walks, voter registration in the South, the Cuban missile crisis, and the assassinations of Kennedy and King, as well as fictional events such as “the great Tompkins Park beatnik-to-hippie conversion ceremony.” Sanders himself enters the narrative through two characters who serve as his alter egos (an underground filmmaker and a dramatist who was once a graduate student in Greek) and a nameless character who owns the Peace Eye Bookstore and who often functions as an observer of the scene. The New York bohemian milieu below 14th Street, known as “the set,” is described in thick detail—the “pads” in old tenements, the cafes, bars, bookstores, theaters, and the two squares (Washington and Tompkins)—with forays to Washington D.C. and Mississippi for political protest and, in later stories, to a commune in Kansas and the rock music scene in Hollywood. As Sanders remarks in the Introduction, “Some locations in these tales, such as Stanley’s Bar and the Charles Theater, actually existed, but others such as the Total Assault Cantina, the House of Nothingness I, the Luminous Animal Theater, the Mindscape Gallery, the I Perf-Po, the Anarchist Coal Collective, and of course the Aura of Health Trans-Truckstop Chow Crib should have existed, but never did.” Stylistically, the work is a mock epic in postmodern hybrid form that merges fact and fiction, realism and fantasy, the classical tradition and popular culture, prose and poetry, drawings, and an idiosyncratic but very accessible comic style that uses neologisms, compound word constructions, hyperbole, satire, and broad comedy that aptly describe a community that combines idealism with the ridiculous, making the point that flawed human beings can yearn for and work towards a better world. An important innovation is the “sho-sto-po” or short story poem, that is, chapters that narrate entirely in verse—long poems that prepare the way for Sanders’ book-length biographical and historical poems of the 1990s to the present.

In paying tribute to his generation, Sanders sought to ground his work and his vision of a bohemian community within a historical context that links the transitory art world that existed for a few years to traditions spanning centuries or millennia. Thus, in Tales, he claims precursors in the work of earlier activists (such as the Yiddish-speaking socialists of the early twentieth century), prior avant-gardes (such as the Cabaret Voltaire of the Dadas), and great writers of the past, especially the ancient Greeks. Two of his short story poems, “Sappho on East Seventh” and “Farbrente Rose,” are impressive poems that combine narrative and lyric and bring into the 1960s history that can be used. Sappho is invoked as a muse by a classics student and writer to endorse the bohemian community’s values of sexual pleasure, innovative art, compassion, sharing abundance, and the collapsing of hierarchies that promotes equality. Rose Snyder represents the “farbrente meydelekh,” or “burning young women” who fought for workers’ rights and a socialist future before World War I, bringing together past and present activists on the Lower East Side. The two stories are linked by their poetic form to give equal weight to two ideals: empowerment through erotic passion and the passion for social justice. Sanders’ fictional places also link rebels of past and present, as the site of the Anarchist Coal Collective in the 1890s becomes the House of Nothingness in the early 1960s and later the Café Perf-Po in the 1980s. Tales ends with a realistic assessment of the successes and failures of the sixties generation. For example, in the penultimate chapter, set in the future, the cast of characters have a party on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the closing of the House of Nothingness in which they share past events of which they are ashamed, while the last chapter, which takes place on New Years’ Eve 1970, has the characters saying goodbye to their utopian dreams as they face a foreseen future of “grasping, greed, and war.” Nevertheless, they are proud of their art and their desire to change the world “without a drop of blood,” retaining hope for a future era of social change.

As a younger member of the Beat Generation, Sanders was a prominent artist in the early sixties avant-garde that generated a postmodern art style and a social rebellion that has had a long-lasting and profound influence down to the present day. Later in his career, he historicized the sixties in works that captured the lived experience and also realistically assessed the accomplishments and failures of his generation. Furthermore, he placed his personal experience in the larger context of American politics and government, fulfilling the role of the modern bard that he outlined in his manifesto, Investigative Poetry.

*******

Jennie Skerl is a founding board member of the Beat Studies Association and Past President. She has published books on Ed Sanders, William S. Burroughs, Jane Bowles, and the Beat Generation as a movement. She retired as Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at West Chester University.

Leave a Reply