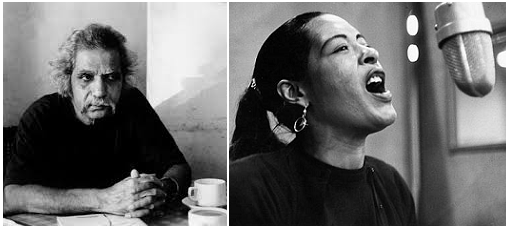

Arun Kolhatkar (1932-2004) Billie Holiday. Courtesy: Getty Images

Darius Cooper

L

ike the alphabet “B” that plays a significant role in the life of Satyajit Ray’s heroine Charulata, this same shabda figures prominently in those poems of Arun Kolatkar where he frequently combines the blues and Rock n Roll from American folk and pop culture with the medieval Indian bhakti tradition of Bhajan culture.

The language of bhakti is supremely democratic. It is offered usually as the language expressed by the common man. In this it resembles the blues which adopted the vocal rhythms of communal labor, the vibrant cries of street vendors, and the stylized shouts of the farm workers as they toiled in the sun. The devotional poetry and the intimate music that was written actually emerged from the verses and songs that were played and spoken. Most of them were invented and improvised by the raw voices and the mangled chords of the instruments producing their body of tunes. The blues singers and musicians in the smoky honkey-tonks resembled the nomadic kirtankaris singing and dancing on the road of their many pilgrimages. The sacred anointment that clung to the sacrosanct syllables of the priestly Sanskrit hymns chanted in temples and the crooningly rehearsed and enunciated melodies offered in elegant nightclubs were rudely displaced by the dusty vernacular idioms of the streets and lanes surrounding the temples and the night clubs.

The bhakti abhangas, like the ones of Tukaram, Kolatkar’s vaadil, were composed of three and a half rhymed lines in the community favored ovi meter, with a signature line at the end connecting the abhang and what it expressed to the personality of its author (“Says Tuka”) both as singer and as performer.

In one abhanga, It was a case, this is how Kolatkar renders Tuka’s Marathi shabdas into a corresponding vernacular blues version in Americanized English.

“It was a case

of God rob God.

No cleaner job

was ever done.

God left God

without a bean.

God left no trace

No trail, No track…

Tuka says:

Nobody was

Nowhere, None

Was plundered

And lost nothing.”

Here God has undertaken to render himself formless. He is determined to erase his many imagined haloes and to empty all the subsequent decorations of worship piled up on him. God is content to become a nobody, so that the very idea of plundering from a nobody-God itself becomes redundant.

We see a similar rendering of the “nobody” idea in Bessie Smith’s Tain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do. Bessie begins by reminding us that “Nobody knows you when you’re down and out/Tain’t nobody’s business if I do.” When life reduces her to a nobody, the world very conveniently abandons her leaving her to confirm her sudden loss of identity. But “If I go to church on Sunday/The cabaret on Monday/Tain’t nobody’s business if I do.” Now the world suddenly intervenes, imposing on her, first, the identity of the pious Christian down on her knees at prayer in Church and the second one, which is that of the fallen woman or whore when she is seen performing or witnessing the cabaret. While she is anonymously respected in the church, she is exposed and vilified in the cabaret. But in these rotating impositions of identities, the I is never allowed to define or resurrect her own identity. That is why she is doing it in her song. “Tain’t nobody’s business if I do” is offered as her prominent signature line.

After castigating the professor, whose poem has been blown away by Bob Dylan’s “a danger wind is blowing,” as “maybe the poem was never any good to begin with” in The Wind Song, Kolatkar actually assumes the persona of the blues musician/singer in Poor Man and expresses the state of his art in the primitive mode of the blues:

“I’m a poor man from a poor land an everything about me is wrong

my guitar is warped and my voice cracks but I’ve written a ‘damned good song’.”

But even though he “plays a poor guitar,” that does not stop him from having “the right to be a superstar.” Hence, like the memorable bums from John Houston’s film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre dreaming of the day they will acquire their gold, he too asks a total stranger, like they did in the film,“brother can you spare a dime?” so that after he has eaten he will continue to work, with a cracked voice and mangled chords on the song that will “make me rich.”

The migration from this individual blues player/singer’s request to the ragged Kala Goda band of lepers is achieved in true rhythms and blues style by Kolatkar in his Kala Goda segment by combining the gyrating references of Big Joe Turner’s “shake, rattle and roll” with the modernist lament of T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. “Come on,” admonishes the noseless lead singer of the band, “let the coins shake rattle and roll/in our battered aluminum bowl.” Prufrocks’ charting of his sad male menopause climaxes with him telling us:

“In the room women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.”

Here, his masculinity is first defeated by the woman being completely indifferent to it and then by the magnificent male bodied sculptures of Michelangelo that surround him in his friend’s study. They conjure up the deformed and hideous masculinity of Kala Goda’s Boomtown Leper’s Band, where once again, the noseless lead singer proclaims the Prufrock refrain:

“Here we come (bang)

and here we go (boom)

pushing the singer in a wheelbarrow.”

The bhakti voice and the blue’s voice mingle in the irreverent tones of Kolatkar’s Biograph. Even the title is a vernacular version of the respectably named genre of Biography. But there is nothing respectable in the narration of crucial incidents related to the poet’s growing up. In fact, most of it is centered around his penis, a forbidden subject he treats here in a very casual way because that’s the way he remembers it:

“Measuring my dick, Baban said

Mine’s bigger, bigger than yours.”

Words he heard in his daily dealings with people like Baban are offered in their original utterances. They are not substituted with euphemisms or cleaned up for polite ears. From innocent games of:

“Doctor, doctor, let’s play doctor”

the poet loses his virginity to “Bunny (who) said/come on in, between the sheets.” The comma after “in” very clearly suggests the first penetration. Later, “squeezing my thigh, a teacher said/Let’s go to the mango grove.” With such forbidden intrusions into his innocent masculinity, there is bound to be trouble. “Grabbing my cock, my wife said/I’ll chop it off one day, just chop it off.” And exhausted after its overuse and submitting it for examination, “Feeling my balls, a doctor said/Hydrocele, I’m sure, hydrocele.”

The last verse juxtaposes very vividly the respectful educated urban response with the spontaneous invectives hurled from the road to what could have been an impending disaster:

“Stepping on my toes, a guy said

Sorry man, I’m sorry.”

But this human concern between two strangers on a crowded street, or perhaps in an overcrowded train compartment, gets progressively violent:

“sticking an umbrella in my eye, another said

I hope you aren’t hurt.”

But all civilized gestures and words, pretended or otherwise, evaporate before the final authentic primitive response:

“Bearing down on me full tilt, a trucker said

Can’t you see where you’re going, you mother fucker?”

In his chapter, “The Uses of the Blues,” James Baldwin refers us to a “state of being” out of which the blues emerge. “They contain,” he adds, “the toughness that manages to make the experience articulate.” He singles out Billie Holiday’s anguish, fed as it was constantly by gin, whisky, dope and men. In “Billie’s Blues” she tells us:

“My man wouldn’t give me no dinner…

Squawked about my supper and turned me outdoors

And had the neve to lay a padlock on my clothes.

I didn’t have so many, but I had a long, long way to go.”

When she sings about what is being done to her by her man, she’s not complaining. Standing up and singing about it, makes her accept it with a lingering kind of stubborn detachment. Things are a mess and there is nothing she can do about it. Still, she can’t just stay there or give up. With only the clothes on her back, she is determined to find her way even though she has a long, long way to go.

Baldwin explains this version of “another kind of blues” very movingly: “a Negro has his difficult days, the days when everything has gone wrong and on top of it, he has a fight with the elevator man, or the taxi driver, or somebody he never saw before… But this particular Tuesday it’s more than you can take–(and) sometimes you know you can take it.” Kolalkar’s Taxi Song is a good example of Baldwin’s “another kind of blues.” The poet is “checking out on my friends” from within a taxi cab. “They know I’m on a drunk” and they know “I’ll come and ask for money,” so they are avoiding him and offering him the proverbial closed door. Locked inside the taxi cab, his captivity has taken him and the harassed driver to “ten addresses” “all the way from colaba to dadar.” An eleventh one still remains: “a friend who stays on Malabar hill.” Advising the angry cab driver “not to stop” and “please don’t shout,” he feels strongly that “there is a chance and if it clicks/he’ll give me a couple of hundred chips” which will pay off the bill. In the last two lines, he evokes the Billy Holiday optimism as he admonishes the cab driver “so let’s try something new man/let’s get a move on”

to the affluent Malabar hill residence.

Like Billie Holiday , the speaker is trying to survive his trouble with whatever desperate resources he has. What is revealing is that the speaker, although deeply embedded, because of his drunken state, within the experience, is still sober enough to be outside it at the same time trying to offer, in true blues style some kind of solution. This enables him to not only express his relationship to the cab driver but also to pass judgment on his friends who “hide or run” constantly from him. He feels that his eleventh friend who once “shared a desk” in school with him and even “the same girl (who) gave us the clap” will give him a “couple of hundred chips,” especially when “he still owes me 27 bottle caps.” That is why he is willing to invite the cab driver to “go someplace and have a drink with me” and assures him that “we gonna have a lotta fun together” since he will be the one who will be paying.

In his essay on “Black English,” Baldwin reminds us that “it goes without saying, then, that language…reveals the private identity, and connects one with, or divorces one from, the larger public or communal identity.” Kolalkar’s Door to Door Blues refers to Kolatkar’s life when it was splashed and absorbed by chronic alcoholism. This poem reveals, very movingly, the efforts made by the poet’s private identity of the drunkard trying “to connect” with the sober communal identity of that “you” who can offer him some temporary shelter, a few scraps of food, and a place to sleep. His alcoholic vision makes him stumble and ring what he hopes is the right doorbell even when “one can’t see the name on the door.” Hunger is honestly expressed. “I could do with a bite.” Shelter is stated without being begged for or demanded. “I’ll lie down in the balcony or here in the passage.” He admits, “I’m completely broke, I’ve nowhere else to go” and assures the “you” that next morning “I’ll answer the door when the milkman comes and I will go.” Drunks are used to constant horizontalities and once sobriety returns with the sound of milk bottles, the healthy opposite binaries to the poisonous hooch bottles, the poet will be on his way after his temporary surrender and respite on the cold apartment corridor.

Kolatkar uses a blues language here in order to describe and control his alcoholic circumstances and not be drowned by a reality that he can still articulate. His language is movingly offered to us out of his desperate and brutal necessity. He needs “a slice of bread or maybe a sausage” to eat and “a floor” to sleep on without “a blanket or pillow.” If that minimum is offered, his drunken identity feels appeased. It not, then it will go looking for another doorbell to ring.

The final verse of Nobody once again formulates this bottomless existence:

“the lift is out of order and you know it for sure

that you will never make it to the ground floor…

You put your foot forward but quietly draw it back

They think you’re already at the bottom and that’s a fact.”

It is interesting that he says “they think.” He, however, is determined to crawl out of this hole.

For Baldwin, blues music “creates” the response to the absolute universal question: “Who am I? What am I doing here?” And he wonders how did the great blues singers and musicians “confront these questions and make of that captivity a song?” Kolatkar’s alcoholic blues poems are all bathed in captivity. They begin in captivity and are created in and by captivity.

In Third Pasta Lane Breakdown, the poet announces this captivity in the first two lines:

“nothing’s wrong with me man i’m ok

it’s just that i haven’t had a drink all day.”

The small i’s is what happens when captivity to a bottle of hooch whittles you down so badly that:

“you’ll have to light my cigarette i can’t strike a match” or

“from taxi to speakeasy is a long way to go

let me hold on to you. i’ll need support.”

The captivity is so intense that every step the alcoholic takes “is like doing a tightrope during an earthquake.” There is no relief. Just a compelling surrender to captivity. So

“let me be down in the middle of the road

go get a bottle of hooch and pour it down my throat.”

This captivity is so compelling that it controls the “past,” defines the “present” and anticipates a “future” that will be willing to be brought also into captivity, and this happens very poignantly in Hi Constable:

“you say I unzipped my fly and pissed on his desk

when the inspector asked my name and address.”

What is interesting is that instead of registering, subsequently, the horror of self-contempt and self-hatred: “Did I do all that at the police station,” the speaker offers us and the constable a confession which recognizes in all his outrageous drunken gestures his personal idea of freedom.

“Yes I know I fully deserve what’s coming to me

please but don’t you see, this time i’ve got to be free.”

His drunken history becomes a shirt he can still wear “ a little soiled but it’s new under the dirt” with dignity and not one in which he can cringe and hide in. His wallet has been “licked clean” and his “watch and pen have been taken” under “clause hundred and ten.” The “week in jail might even do me good” because he is now a free man who expressed his freedom authentically out of his captivity to drink.

He reminds us of Leonard Cohen’s:

“like a drunk

In a midnight choir”

]who has tried, in his way], “to be free”

Charlie Chaplin’s urbanized tramp, who was the consummate gentleman bohemian shuffling from pavement to pavement in his in search of a daily meal and nightly shelter bears a striking resemblance to the vagabond Tukaram whose insane love for his God Vithala made him loaf and sing and dance in the lanes of his village day in and day out. Kolatkar captures the Chaplinsque traits very well in his blues bhaki translations of Tuka’s abhanga, in Who Cares for God’s Man, Tuka says he is “cousin or companion to no one/He’s beyond reclamation.” To reclaim him would be to rob him of his unique independent personality as the wealthy millionaire tries to do when in his sobriety he fails to recognize the dirty tramp now fast asleep beside him on his luxurious bed and has his butler throw him out in Citylights. Like the tramp “they call Tuka idle, a madman” because “he becomes a problem for everyone.” Tuka’s wife, in terms so reminiscent of blues singers like Billie Holiday, offers us a searing description of her wayward husband who has so openly replaced her with that damned God Vithala. In Don’t Think I Don’t, she castigates him in true blues style:

“Don’t think I don’t

Know you, you swine.”

The “swine” here, however, is both Tuka and Vithala. Victimized by both as Billie was with drugs, drink, and men, she wonders as Billie did:

“Is this humiliation

to last forever?”

and then in the fierce spirit of the wounded blues singer, demands

“What I want

to know is

What good has he done

the two of us?”

Here her anger is unleashed on the God who has so cruelly replaced her. But at this moment, Tuka intervenes and informs us

“The woman’s in tears,

Says Tuka, she sobs”

And then in a marvelous reversal of her grief, like Billie’s he tells us

“Then she laughs

And then again sobs.”

That is her blues way of responding to a “God’s idiot.” You have to laugh (and cry) at the impossibility of her absurd situation. In What Now My Son, she tries to come to turns with it as the battered female blues singers constantly did. Tuka’s “castanets get the jitters” in the same ways as the warped chords of the blues and wailing musicians did and

“When he opens

His ugly mouth”

to sing in the temple, he reminds us of Billie’s swollen lips belting out her anguished blues in the night club: “Home has little use for him,” his wife complains for “he would rather be in the jungle.” Her estranged words personify the same grief found in Bessie Smith’s Empty Bed Blues:

“I woke up this morning with an awful achin’ head

I woke up this morning with an awful achin’ head

My new man had left me just a room and an empty bed.”

When Tuka intervenes to remind her that as:

“Tuka says

This is only

The beginning,”

in addition to being the wayward husband who has committed from her jaundiced perspective, both adultery and idolatry with Vithala, he has also become, along with his other besotted Kirtankaris, “enduring bums,” and in the abhanga We are enduring bums, he lays out this Chaplinesque philosophy, in the appropriate idioms of the blues musicians:

“Get lost, brother, if you don’t

Fancy our kind of living”

because “There’s no better way

Of growing to greatness of soul.”

In another abhanga, There’s no percentage, Tuka reminds us, once again, in a memorable blues tempo:

“There is no percentage

In being renowned”

When the dialogues of the blue’s musician with his/her songs and instruments reveal the same greatness of soul that Tuka’s dialogues with Vithala did. Vithala and the Blues become “the great all timer” that Tuka and his Blue brethren, as enduring bums “serve.” Every time that happens,their “Harvest’s done.”

Kevin Whitefield in Why Jazztells us that in a blues song “major keys are generally considered optimistic, and minor keys sorrowful. To play both at once reinforces the blues’ simultaneous acknowledgement and defiance of hard times.” He singles out Jimmy Rushing shouting on Count Basie’s “Boogie Woogie of 1936:

“I may be wrong but I won’t be wrong always.

And I may be wrong but I won’t be wrong always,

You’re gonna long for me baby one of these rainy days.”

A similar boogie woogie is attempted by Kolatkar in his ‘song version’ of Three Cups of Tea:

“I didn’t knock, the door said push, so I pushed my way

I didn’t knock, the door said push, so I pushed my way

i stood in front of the manger, i said i want my pay.”

As David Hajdu reminds us in his “Hip Hop” chapter from Love for Sale, “violent imagery had an important place in an outlet for rage…and the reasons for the violence were…personal…a broken heart, wounded pride, maltreatment by the boss.”

The key word in Kolatkar’s first three line is “push.” The speaker has been pushed so hard by his boss that he decides, after summoning up the courage, to push the door and stand before his boss to give him his pay. He wants to take it from him because that is his right. He has worked hard for it and he feels he has earned it. The repetition of “push” in the first two lines manifest in true blues style, his major keys resolve.

The boss’s reactions are condescending, mimicking the aggressive demands of the speaker:

“He looked up and said you’ll be paid on the first with all the rest

company rules, he said, you’ll be paid on the first with all the rest.”

“i picked up his watch, it was on top of his desk”

Instead of creating fear in the accustomed minor key reaction of the speaker, the boss’s attempt at humiliating the speaker only adds more fuel to the speaker’s major keys demands. When the speaker picks up the manger’s watch and threatens to pocket it or break it, a new recognition of his personality, ready for any kind of confrontation, emerges before the boss, and before he can react to this act of insubordination, the emboldened speaker goes even further to reinforce his demands, issuing categorically, a resolute challenge:

“i said pick up the phone

call the cops i said, just dial one 00

according to my rules baby, i get paid when i say so.”

What we get here is a clear enunciation of wounded pride. The speaker wants the boss to quit behaving and speaking from the company’s official script. He wants the boss to respond humanely to his brutally but honestly offered first person singular demand. He wants to be paid now for his labor, even intimately via the ‘baby’ reference, and not on the first of the month with “all the rest.”

The blues have the capacity to equalize everyone listening to them; they offer compensations, so that personal humiliations can be shelved or forgotten for a while or even transcended via the music’s near tragic lyricism. As Kevin Young, in his “Foreword” to Blues Poems puts it, “For in spite of navigating the depths of despair, the blues ultimately are about triumphing over that despair–or at least surviving it long enough to sing about it.”

In Backwater Blues,Bessie Smith begins by talking about a flood that engulfs her and a lot of people because “It rained five days and the skies turn dark as night.” It worsens “When it thunders and lightin’ and the wind begins to blow” leaving “thousands of people,” like her, who “ain’t got no place to go.” After equalizing the despair, she offers a wonderful compensation via the two “mmmmmmmmm’s” reflecting:

“Backwater blues done caused me to pack my things and go

Backwater blues done caused me to pack my things and go

Cause my house fell down and I can’t live there no mo.”

Kolatkar’s Song of the Flour Mill offers us the same equalizing compensatory idioms of the blues. The “chugchug chugchug chugchug” song of the mill as it grounds the flour in the “rollers (that) spin inside my body” equalizes all those who have brought their jowar for this purpose. “Whether you’re a young woman/or an old hag” makes no difference to those belts of breath churning inside:

“Whoever you are, woman,

Brahmin, ghatan, whatever,

makes no difference.”

Once the jowar is placed inside the rollers, all caste distinctions, from the upper class white Brahmin woman to the dusky untouchable maid/ghatan, break down.

“Whether you’re dagdu, thondu or pandu,” all

toms, dicks, and harrys, become “one to me” as

their jowars mingle with each other.

The “boss” is ordered “to back off” because the mill has gone “Kill crazy” in its determination to equalize all. It even “swallows the mother of us all” in “just one gulp” and the compensation that is created goes beyond the caste distinctions:

“sweet? bitter? sour?

the mill does not know

and the mill does not care”

because the flour that will be eaten by all will taste the same, so why make a fuss about it.

In Love for Sale, David Hajdu, acquaints us with “a musically stripped down lyrically juiced-up form called jump blues.” In them “the lyrics were mostly slangy celebrations of the pleasures of gin, reefers, and other sources of taboo kicks.” For Kolatkar, these blues occur when “from legend’s ledge the hero falls” and as a sorry spectacle becomes In a godforsaken hotel:

“in a godforsaken town

(where) a spider will watch

me masturbate

from the sneering corner

of a neurotic.”

He feels he does not belong, either to the world, or to himself, and the only consolation is to indulge in the taboo licks of “the booze” that the unzipped suitcase will provide, so that under its steadily growing influence, he will “beat” the seat of his masculinity in the taboo kicks version of “black and blue/till it’s a limp and sad oblong/bonggggg.”

This is Prufrocks’s lament, once again, but stretched to its ultimate limits, and when those limits are measured, they reveal

“what am i like? open and see

precisely nothing in a lot of boxes”

No more sure of himself, he is “going round in circles” having abandoned, somewhere and sometime, a familiar “earthed axis.”

Since Tuka,

“was not above lifting whole verses

whole lines when it suited him”

Since Kolatkar’s verses “are a lot of words,” let me “replace them with others/(and) substitute my own,” in the improvised modes of the blues musician and the bhajan singer:

Each of your poems

with its drips

of the bhakti and the blues,

moves so movingly

in its own palki’s orbit.

Your sense of alienation

hibernates in their midst

like crabs.

But as yesterday’s bhakti singer

and today’s blues musician

you laugh

as you ride rough-shod

over both,

particularly where

the territories overlap.

But look, look,

the bluesman is tiptoeing back

leaving his guitar

besides Vithala’s idol.

So is it safe?

Is it sane

to hang around,

when Vithala takes up the guitar

to finally have his say and play?

to finally

have

his say

and play?

*******

Darius Cooper is an essayist, poet and film critic. He has written on Guru Dutt, Satyajit Ray and published essays and reviews in India and USA including The Beacon.. “Aavaan Jawaan” is his latest collection of poems. He is an editor with The Beacon webzine..

Darius Cooper in The Beacon

Thanks. Enjoyed reading this thoroughly. Sent me back in search of the Blues songs I had forgotten. and the surprising reference to The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (a brilliant film version, even as the fine novel by B. Traven, on which is is based, has been largely forgotten).

What a fare from Dariaus’ quill! Delectable.

Apologies. Darius spelt right.