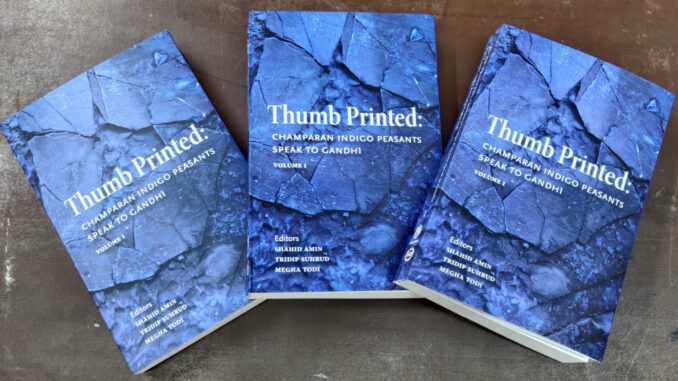

Thumb Printed: Champaran Indigo Peasants Speak to Gandhi Edited by Shahid Amin, Tridip Suhrud and Megha Todi Navajivan Trust and National Archives of India. 360 pages / Rs 500

Shahid Amin, Tridip Suhrud and Megha Todi

I

t is difficult to capture the voices of peasants from our colonial and pre-colonial pasts, for peasants of those times didn’t write, they were written about. Petitions and Memorials framed by scribes, confessions wrenched in police lock-ups, depositions nervously uttered before Magistrates — these are the usual conduits though which the voices of ordinary folk make their way into historical records. In a few instances, it could be a jeevni, the autobiographical account of an exceptional, literate peasant, that illuminates the lives of the unlettered — those who produce goods and services, not documents. It is rare indeed when thousands of peasants seek out a Mahatma-in- the-making and recount in telling detail the onerous conditions under which they toiled for the nilhe(sahibs) — the Indigo-sahibs of Champaran.

The arrival of Gandhi in the District in April 1917; his desire to make inquiries into the indigo situation and his momentous disobedience of the order to vacate the district; the official turnaround in permitting his investigations, leading to the appointment of a high-powered commission, with Gandhi as the peasants’ advocate; the abolition of the existing variant of the tinkathia system of indigo cultivation on peasant holdings .… These are the motifs common to most accounts of Gandhi in Champaran. This, however, is to foreshorten his encounter with the ‘indigo peasants’, a move unwarranted by Gandhi’s own views and his exertions in the District.

It is tempting to visualize Gandhi’s assistants writing up the peasants’ izhAr– lit.to articulate — (Rajendra Prasad’s words). Hundreds of peasants have gathered at Hazarimal’sdharamsahla, an outwork of a factory or, to deploy a colonial trope, ‘under the cool shade of a Banyan tree’. As there is no roll call for peasants to come forward to ‘testify’, there is some confusion as to who goes first. Oras seems more likely, a small crowd gathers near the writing table of Dharnidhar or Rajendra Prasad. The peasant, or a group from the same village who gather round the desk are asked a routine set of questions about their….? It is doubtful whether they were simply told, as often in a court of law: ‘ tum-kokyakahnamangta?’ — ‘go ahead and tell what you have to say?’ in local Bhojpuri. More likely, MotiRaut, resigned to submission, the boy Afdar, forced to graze large herd of cattle on the field of Raj Kumar Shukla, or Jhunia, the disconsolate old widow, is asked to repeat, or pause a bit so that a Dharnidhar could write down their story. It is quite surprising that there is only a single case of crossing out and rewriting, and that too in the case of an affirmation taken down — no doubt with some lingual assistance — by Gandhi himself.

This veryGandhian mode of eliciting information was a radical move that encouraged the peasantsto speakabout their lived experience –bhogahuayathAarth,as one would say in the correct Hindi of the region. Gandhi’s Inquiry consisted in getting the testimonies of peasants, spoken in local Bhojpuri, translated and transcribed into English by his lawyer assistants. The Inquiry was to be of a quasi-judicial in nature: it was open, peasants were to be cross-examined and their thumb-prints along with the signature ofthe recorder-transcriber formalizing the averment. In a good many cases, peasants actually wrote up their signatures in the local kaithi script. There is even the solitary case of GajadharMahton signing his name in English.

These testimonies, to use that hackneyed phrase, speak for themselves. To forsake these peasant voices for a generalized politics of the ‘Champaran Satyagraha’ would be to undercut the ground from under the feet of the Mahatma at the very moment of his making.

Between April 16, 1917, and June 13, 1917, Gandhi and his associates spoke to and recorded the testimonies of 7000 peasants.

How these volumes runninginto several thousand pages reached the safe coffers of our national repository is a story worth telling. ShridharVasudevSohoni, the Commissioner of Tirhut Division in the mid-1950s, hasnarrated his discovery of these folios in the record room of his office in a somewhat dramatic manner. This was the same office from which L.F.Morshead, his colonial predecessor, had ordered Gandhi to be externed. Sohoni tells us how at the end of a day’s work in August 1955, he chanced upon a worm-eaten bundle of papers which turned out to be the collection of these peasant testimonies. He showed these to Rajendra Prasad, Gandhi’s trusted lieutenant, now the President of India, who was immensely pleased at this discovery and wished copies to be made, with the active involvement of Ramnavami Prasad, one of the original band of testimony recorders. The President also desired that one set of these registers be made for his personal collection. Few months later Mritunjay Prasad, the President’s son, gave some of these Registers to Commissioner Sohoni. It appears that five typed volumes of these peasant affirmations were deposited soon after in the Sadaqat Ashram, Patna, the Ashram founded by MaulanaMazhar-ul- Haq, a close friend, referred by Gandhi in the original Gujarati version of his Autography as the ‘Simple Bihari’- lawyer nationalist.

Basing himself on these hitherto unknown volumes, K.KDatta, the foremost historian of colonial Bihar, conveyed their discovery to the Indian Historical Records Commission in 1958. The full set of eight folio volumes, along with an index, were handed over by Mritunjay Prasad to the National Archives in early November 1973. These clearly are the original manuscript set of testimonies, for the thumb impressions of peasants and the signatures of the lawyer-transcribers have remained un-smudged by the passage of time. In a sense, this is what Gandhi had in mind while issuing detailed instructions for ‘workers’ for the recording these peasant voices — a collocation for immediate use for his personal understanding of the situation, and as historical document. And what an archive it has turned out to be!

The first volume of the proposed eight, contains 378 testimonies.

***

[1] Gopal, Village GajpuraChathauni, Factory Motihari

Motihari

25.5.1917

Gopal, son of HiramanLohar, of TolaGajpura, MauzaChathauni, Motiharikothi:

My father Hiramani Lohar is living. I am living with my father. I have a cousin Nepali who is living with his father Musahar. We have 6½ bighas of land. On Sunday last, nine men belonging to the kothi including gumastha SarvarRai, Godni Butan, Butan Dusadh and a molazim whose name I do not know came with a cart to the kharihan[1].SarvarRai was about to remove bhusa belonging to me us.[2] I was not in the field at the time. About evening I observed that factory people were beating my father. I in common with others intervened. My father was at last released. I and my cousin Nepali then began to walk towards Mr. Gandhi’s offices in Motihari. Six cartmen and SarvarRai ran after us and caught us, beat us and got us on the cart, took us to the kothi. At about 10 p.m. the Sahib Mr. Irvin came. The factory people complained that the villagers would not allow them to take bhusa and that they drive them away. We wanted to make a statement before the Sahib but he would not listen to us and beat us both, Nepali more severely than me and ordered that we should be fined and kept in the fowl house [murghikhana: a detention room within the factory]. We were to pay Rs. 10/-each as fine and talbanaRs. 1/-each to the factory men. SarvarRai taking pity on us released us at midnight, but only on my saying that the fine would be paid in the morning. Next morning Liladhar, our mahajan undertook on our behalf to pay Rs. 22/-.

It is the kothi practice to take by force bhusa from the raiyats.[3]

[1] Threshing floor [2] Crossed out by Gandhi, who is recording the testimony. [3] Though the name is not mentioned the hand clearly suggests the above testimony was recorded by M.K. Gandhi.

**

[2] HiraRai, Village Man Karania, Thana Gobindganj, Factory Khairwa

Bettiah

8.5.1917

I, HiraRai, son of Dharichhan Rai Rajput, age 36 years, resident of Man Karania, Thana Gobindganj, under the Khairwa outwork of the Turkaulia concern, state as follows:

I hold 2 bighas 8 cottahs and 1 dhur of land. We had been required to grow indigo on the tinkathia system from year to year upto 1319F, when it was stopped by the factory. In 1320F, we were asked to execute agreements for sarahbeshi by the factory men. We declined to do so. Thereupon we were prevented from taking water from the village wells by dhangars of the factory being posted there, our cattle were not allowed to be taken to our fields. Ramdayal Rai, Balkaran Rai and Anurag Rai and Muneshwar Tewari of my village approached the Sahib on behalf of all of us in this connection but he refused to listen to our prayer and insisted upon our paying sarahbeshi. We filed a petition before the Collector, stating all the above facts and praying that he may be pleased to ask the Sahib of the factory to withdraw his sipahis from our village and not to harass us and we even said that we had no objection to growing indigo as usual, if we were spared these harassments and not asked to agree to enhancement of rent. The Collector passed an order to the effect that he had no power to pass the order prayed for on 5/5/1913. I beg to file here a copy of the aforesaid petition.

In the following Bhado, Kunja Raut Kurmi, Deodhari Misser, Kiswar Tewari came to my house and asked me to accompany them to the factory for the registration of the sarahbeshi agreement. By this time all the tenants of the village had been made to enter the agreements, which were furtherwith registered. seven out of the ten men, who were signatories with above mentioned petition presented before the Collector, had also done so. So when the sipahis of the factory came to take me for the execution of the sarahbeshi agreement, only three men including myself were left. I refused to go but two of them caught hold of my hands, and KeshwarTiwari posted himself behind my back. In this way I was taken to the kuchery of the factory. Before the Sub-Registrar, I declared that I would not put my thumb-impression. The Sub-Registrar asked them to remove me from that place. But KunjaRaut literally thrust me out of it. Rambhuj Singh, the jamadar of the factory and RamlachhanRaiSajawal came and told me that when all others had signed, it was no use fighting the factory and that I should execute the agreement or I would be a ruined man. I was again produced before the Sub-Registrar and my thumb impression was secured on a paper, which had been kept only filled up, and it was forthwith registered.

Since that year enhanced rent has been realised from me. I had to pay in 1319F only Rs. 7/3 as rent but in 1320F Rs. 9/14/2 were realised from me. Since that year I have been required to pay this increased amount.

The Assistant Settlement Officer has allowed the enhancement. I stated to him all the facts connected with the execution of the sarahbeshi agreement and filed the receipts of previous years.

I do not supply ploughs to the factory. I was a Thikaha peon[4] of the Kothi from Chait of 1323F to Posh of 1324F. I used to collect rents from the tenants of Panditpure and Berahimpur. I realised one anna to two annas from each tenant and got my daily food from them. I used to get Rs. 3/-as my pay and used to earn about the same amount from outside. As the people, with whom I had to deal, belonged to villages adjoining to mine, I did not beat them or take anybody’s cattle, if the rent was not paid on demand. The molazims [lit. paid employees] of the factory such as Keswar Tewari, Deodhari Misser, Kunja Raut used to realise /8/ annas to one rupee as talbana. From a tenant they realised even Rs. 2 to 3/ in Bhado last (1323F). On refusal on the part of the tenant, they would take away his cattle to the factory, and it was only when the money was paid that they would be released. If they demanded a rupee as talbana and a tenant pleaded his inability, he would be beaten. They would sometimes take him to the factory and report to the Sahib that the man has not paying his rent and that when they had been to his place, he and the other members of the family had taken out lathis to assault them. This would enrage the Sahib and he might order him to be bound and thus realise the dues from him. And then people would tie him (the tenant) to the ‘siso’ tree, which stands in the front of the kuchhery. And it was only when the talbana is realised from him, and a rupee is paid to the clerk of the factory that the man would be let off, and some time given to him to pay his rent. In 1322F, I myself had to suffer in this way at the hands of Kunja Raut. I also observed this when I was an employee of the kothi last year.

Thumb Impression

Sambhu Saran Verma

[4] Thikaha peon, from Thika = Thicca, a short-term arrangement. In this means a peasant who functions for a short period as one of the peons of the factory, responsible, in part, for collecting rent from his erstwhile peasant comrades. In this case from March-April 1916 to December 1917.

**

![]()

![]()

[3] DuarikaRai, Village Bhopat Maharani, Thana Kesaria, Factory Jagirha

Motihari

22.4.1917

Statement of DuarikaRai, son of ZalimRai, resident of Maharani Bhopat, Thana Kesaria:

Complaint against Jagirha

After selling off my lands to pay creditors I had 3 bigha-10 cottah in my village. In 1321F by force and compulsion I was made to write sarahbeshi in Poos and in Baisakh [roughly December and April as instalments for Kharif and Rabi crops] of the same year as I could not pay off the arrear at enhanced rates, the factory forcibly took possession of 2 bigha-10 cottah. In 1322F and 1323F I did not pay rent.

This year also I had not paid rent. The factory demanded Rs. 21/-for that one bigha and on my inability to pay, the PatwariDuarikaLal, GulliRautGumastha and the peon DhuniRai and one more peon, whose name I do not know, broke open my tatti[1] and forcibly dragged my wife to the shade under a Pakar tree and took thumb impression of my wife. They have entrusted the crop of my field to JudagiriChouby as well as the field itself. It is thus the factory intends to dispossess me. (Note : The witness is shedding tears while relating the incident.) All this happened on Friday last. RoghuniRai was present there. There were other tenants. I can’t say if they will give evidence or not: there is so much terror. The occurrence did not take place in my presence. After getting scent of the arrival of the factory servants I had left the village and on my return back I learnt of the occurrence from my wife; also from Roghuni.

Dharnidhar Prasad

[1] Tatti: A screen ‘door’ made of bamboo and reed, a sort of entrance to a peasant dwelling place.

**

[4] MangraChamar, Village Man Karania, Thana Gobindganj, Factory Khairwa

Bettiah

9.5.1917

Statement of MangraChamar, son of Khubhari, aged 15 years, resident of Mowza Man Karania, Thana Gobindganj, under the Khairwa concern:

I am a Chamar by caste. My holding is in the name of JagroopChamar, my grandfather. I am now in possession of only 2 ½ bighas of land in Man Karania and another 2 ½ bigha in Balua. I corroborate the statement made by MahadeoRai and others as regards compulsory execution of sarahbeshi.

My further complaint is that from time immemorial it has been the custom, that when any cattle died in the village, it was the duty of the members of my family to remove the dead cattle and we were entitled to its skin. We had to supply in its stead country-made shoes to my co-villagers, free of cost, and to do other sundry works for them. We had also to pay Rs. 7/-only per year to the kothi for this monopoly. For the last seven years, after the dead cattle is skinned by us, it is forcibly taken to the kothi, and we get nothing in return for our labours. I am told, the kothi sells these skins. The kothi does not charge me Rs. 7/-per year since it takes the skins from us.

I am in great difficulties these days, as I can’t supply shoes to my co-villagers, which my family had been doing.

The rent of my holding viz. 5 bighas used to be Rs. 20/-only, now I have to pay Rs. 25/-only according to the sarahbeshi.

Thumb Impression

Raghunandan Prasad

*******

Tridip Suhrud in The Beacon

Leave a Reply