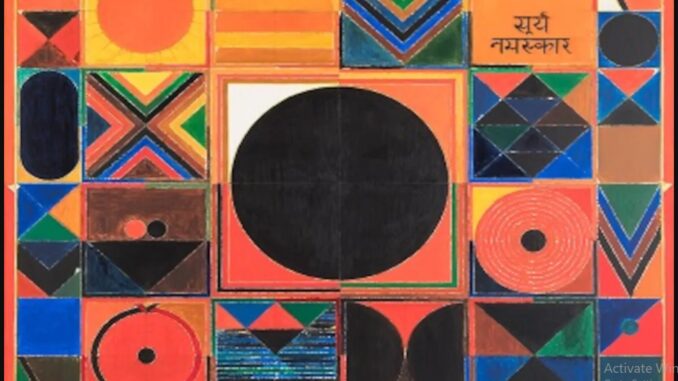

S.H. Raza Surya Namaskar 1995

Bibhu Padhi

1.

I

f you are sensitively, cautiously–and not merely intelligently–watchful, you can almost see the blinding, rough-edged “thoughts” rushing in. I suppose there are two ways of dealing with these: one, to make yourself sufficiently “opaque,” so that they can not seep into the porous skin of the little house of your mind; the other–though the more difficult but necessary way–is to make your all-accepting heart sufficiently transparent so that the thoughts pass through it and away just as sunlight passes through the magically attractive, air-thin transparency of plain glass.

Our problem is, we can make ourselves neither—in fact, we do turn ourselves even a little sticky. The thoughts get stuck to us. It is difficult to banish a thought once it sticks onto you–the free-flowing blood loses its right pressure, the lustrous skin its true colour, beyond all possibilities of regaining its vibrant transparency, so much like those winds that stick purposelessly to the old, brittle bark of a long forgotten, unnoticed, now-sapless deodar tree.

How to make ourselves opaque or transparent? By making ourselves opaque we turn our mind into matter–solid matter through which nothing can pass. This is the state that the true sadhak (saint) enjoys. His body is his Himalayan wall against heartless invasions from the darker quarters of doubt, restlessness and fear. And, by turning ourselves transparent we turn our mind into ether. This, too, is a state that is a characteristic trait of a true sadhak. How to turn the usually sticky, bubble-gum-like mind into the solidity of objective space, true in its opacity, or into the fineness of ether with its true openness? I have thought over the matter a great deal and have failed to reach an answer. I know, I can neither turn my mind into the opacity of matter nor into the openness of ether. I also know that, in the process, I have lost quite a few nights’ sleep and rest.

In fact, a large part of what I feel about myself and the world and myself, is often tainted by thoughts of paradoxical kinds. The thoughts in themselves are not contradictory, no, not tricky either, for thoughts are thoughts and cannot be judged one against the other. Is it the stickiness of my servile mind that makes them appear so? How to get rid of it? Once in a while I have been successful in creating my opacity or my ether, but they have been for brief whiles only. To continue this briefness over a stretch of time, one needs love–plain, unasked for, sky-blue, or leaf-green love. A lot of it.

The sunlight of knowledge must dry up the sticky substance within my mind and make it, to start with, somewhat dry and amorphous, so that thoughts that come near it, instead of sticking to it and showing themselves to me teasingly, get lost like drops of water in a large bowl of fine grains of sand. I pray to achieve at least this much.

2.

I have been spending a large part of most of my days lying down on the bed, thinking of so many things. Of nothing. Just looking into the emptiness of space and time. I do not feel like doing anything except work related to the body. I read somewhere, “Being alone is the true state of man.” I have been living in a continuous state of aloneness over a long length of time, but also troubled by mean earthly things. Again, nothing. Sometimes I tell myself, let me be alone, the things will take care of themselves. They would not leave me however, and they are so many. I know, no one will bother to count them. Even the slightest of these dramatizes itself in the heaviness of the head that I feel so frequently.

The frequent, pulsating pain radiates all about it, deep inside it, as if it was creating large, black holes inside the brain. Each day, each moment of an unrecordable time. My troubled neurologist calls it “migraine” and prescribes a set of neat, round, pinkish tablets whose high price promises a lot but is vastly unequal to what they offer. I am ready and quick enough to forget and forgive the neurologist’s naive ignorance both about matters of the lonely, helpless pain of a forced imprisonment and about the quiet, self-assured, meditative joy of being free. It seems as if, quite simply, I don’t deserve it. You couldn’t do anything more or less than what I have been doing for the past 32 years of nurturing a mysterious wish to suffer the lean nights of deprivation and privacy.

I wonder if there is a healthy way to keep the mind separate from the world. The world of things with all its elusive manifestations, mysteries is a tricky little place indeed. It is almost ready with its problems, its desires and expectations. I have never tried hard to treat the world as my lover, but, like most others, I have gone through love-–plain human love-– and I know its dark consequences. It is dangerous to dissatisfy one’s lover, to ignore the world.

What I need to find beyond these dangers is the grace I have heard so often about, felt once in a while, but have been sadly unable to sustain those moments of “arrival” over any period of time.

It is grace alone that can rescue you from “bad” love, the world’s cruel intricacies, the promised fame and all the lows that are its inevitable, peremptory extensions.

What does one do to receive this grace continuously, without interruption, except by a continuous, uninterrupted process of self-effacement? I do not exist. That should the theme-song of my entire existence.

I do not exist. What exists is a dream-vision of my own calculations about myself–-I am this, I am that. I have this. I enjoy these, I hate those. I love this woman, I can’t stand the voice of that man. I love this child of my own making, this wife of a lifetime. I don’t need those others who don’t like to “show” their being alone, for I do. I have the ability to transform the world. I am the little master of the universe.

Such statements only drive one into those devilish delusions that negate grace. And yet I make those statements. I wish I had lost all language to describe myself, I wish I had no language–a mouthless, toothless child whose only language is a lost, breathless whimper.

I have seen how grace resplendently dances over an early-morning, new-born skin. What I need is a new birth—a birth that would not belong to this world but occur somewhere in the nameless distances beyond measurable time and space. Just the other day my younger child asked why those intriguing “sines” and “coses” are there in his little world of trigonometry and I remember telling him that that was because we were supposed to know the angles our frail eyes make with a certain planet or star and are supposed to be measured carefully and known precisely in order that we might talk loudly about our neighboring universes, galaxies that are 300 million lightyears away from what we are. Intelligent beings. The most intelligent being that walked one of the Creator’s most colorful landscapes. That’s why the “sines” and “coses” are there.

Not to know ourselves, but to be biased by the supposed truth of light-years. Just one light year. Half-a-light-year. One hundredth. A trillionth. NO. A big NO to all this trash we have been so far taught to believe to be right, and, almost brutally, to remember, get by the heart. As if the heart (poor heart!) didn’t have anything else to do. Like falling in love. Like feeling its own healthy cholesterol-free beats. Like smiling in its childlike innocence at so many things that the world finds valuable, and hence must be possessed by everyone, by all means, mortal or otherwise (by hook or crook, perhaps mostly by crook!).

Yes, I want to be, I need to be a child, a new born child, asking for nothing, knowing nothing, caring for nothing except the jet of divine milk that the generosity of the heart alone can give–a child like a spot of light that has no source, and is directed at nothing.

It only glows on its own humble, self-produced and self-directed luminosity, like the stars in the glorious firmament of our dark, much self-conceited, yet-to-be- discovered selves–-self-fulfilled and self-fulfilling, like grace itself.

Is grace by any remote chance hovering above me? I wonder. Is there a blessing, a far but a small blessing, fervently waiting its allotment to me hanging somewhere out there, far within the distant, night air?

Will someone, someone who knows where blessings are and cares little for their being stolen by famished thieves of love, take me by the hand and lead me to its moist, sticky kindness? There must be someone. Else, the world wouldn’t exist. Else, I wouldn’t be anywhere around now. Someone. Just for now.

He being what he is, he may not forget me, for my God doesn’t, but I will. For His sake only. Only for His sake. Believe me. And I don’t know what a lie is. No, I don’t. Otherwise by now, I think I would be a king. With a hundred thousand wives. And I don’t know how many mistresses. An endless sequence of belly-swirling, skin-licking girls from the Arabian Nights.

I love to be a beggar instead, and I need to remain one through the whole length and breadth of an unimaginable time, an incalculable space. In my next life. In India, Pakistan, Siberia, Nigeria. The Island of Cloves. Lawrence’s New Mexico. The Texas wilderness, the Californian deserts, the Sahara Gardens. With Ungaretti in Italy, in Argentina, with Borges. In Chile, with Neruda’s sixteen love songs and that devastating “A Song of Despair”; his residence on the wuthering heights of Machu Pichu. So many, so much!

One never knows where needs end and wishes begin. We want everything, all that may not be our own. What else are we? We hardly know it couldn’t be what it is not. We are beggars. All, all of us.

My God loves to beg too. That I know. I feel so privileged, happy! Hence, I give. They are very small things in fact—like a word, a sound, a piece of silence. And I die everyday to give, whatever I can, whenever, in my own small ways, but never, yes, never, waiting to fix a price. He asks for things. It is rare that I do not have those with me. So it has been; so it will always be.

I beg too. For small things. Like grapes and kisses, the salty sea-breeze, oranges, date-palms, chilled water straight from the fridge to run smoothly down a dry, featureless throat, especially when my thirty-six-year old lover, Migraine, is with me. A once-in-a-while drop of whisky. Small things, but they matter. I get these, given freely by a beggar-god who however is rich enough for these little things, these gifts of a lifetime. So it has been, and I hope, so it will be. I don’t know what others think. Could it be the same way I do? Could be, for there seems to be no other way to tell an old story but one that would be fondly cherished like what must be the infinitely fine but forever-lost memory of a new birth, the exact moment of the soul’s recovery from a going, ending-body’s last, ultimate hardships.

3.

A week ago I wanted to be sure about the colour of blood—regular, healthy blood. Red? Maroon? Brickish? Crimson? Brownish red? Reddish brown? Close to being the tangled branches of bougainvillea creepers living so passionately, in such exuberance that these eyes would envy the very look of their throwing themselves all over the asbestos roof of the residential quarters of the local Divisional Forest Officer?

Blood. Like a long left-out lump of the stuff on a friendless road. I couldn’t be sure, although I knew there was something about the dark night of the veins and arteries, the slender capillaries randomly distributed over the body’s interior texture, under the thin skin, roughened by the Indian summers. I wasn’t sure.

Until this morning’s early, dusky hour, when I woke from a dream that foresaw thick–real thick–blood, turned to my left, my body’s weight suddenly rushing into my forehead and skull; I don’t remember. I think I fell a long way down and hit something just under the mole mark, below my right forehead’s hairline. The devil was waiting for it, and I had guessed as much.

But there was no way out except making oneself docile enough to give in to his desire, a small yet profitable desire to draw human blood out of where it really belonged over the centuries, suck it whole, without adding any unnatural spices or flavours (for human blood is human blood and didn’t need the hangman’s lime). I suppose the devil knew it tasted good that way, without vinegar, pepper, or salt. For, this blood had all of that already. The smell of vinegar, the heat of spices, a large sprinkle of salt. And a lot more.

Also by Bibhu Padhi: The Blissful Center and Other Poems

I still didn’t know the colour. My hands felt for something dripping onto my eyelids and swapped it out with my long fingers, now in a friendly togetherness. Something sticky, not quite like gum, rather close to the adhesive property of Fevicol before it dries up on the soft edges of an unsealed Indian envelope folded in and out of some flimsy looking paper. My fingers felt just as flimsy and dispensable.

My younger, 14-year-old son was the first to notice something gone wrong on the bare bedroom floor. He asked his mother to put on the soft milk-white bulb. It had fused out. She put on the tube light, under whose not-so-sure glow, I saw something familiar but after the lapse of a long time—twenty-seven years, to be precise, when I had nothing to offer the thirsty world except my younger blood, vomit it out for it to lick its colour clean off the clear floor of our College Square house in Cuttack, which my father-who-died-young had built with his precious blood.

He died early, of kidney failure. At that time there was no facility at the local SCB Medical College Hospital for dialysis, to keep the dying tentatively alive. He was 48 and a very sad man. I can clearly recall the colour of his blood: a deep malt-brown, in lumpy, trembling sizes and shapes, like a freshly dissected rabbits’s neat little heart, half-resting, half-jumping upon the steady palm of the hand that had so meticulously dissected the little animal with a throbbing, dancing life.

I recall the evening when I fell down on the mosaic floor and bled. My wife cleaned the blood with a grimy piece of a much-used kitchen cloth as my child looked on from above the double-bed with the stunned eyes of a cat. Spilled blood must be cleaned soon enough not to allow the dead to lick it with their pale white tongues. My blood was no longer mine but had become the ancestral property of the early morning spirits of the family, as I sat on the cold floor, gazing at the blood spread, spread, until what remained was only a memory and a loss.

But, the hollow pain now almost forgotten, I still needed to know what my blood smelled like. The nearer things must be felt and known—for they alone are what we are as nothing else is.

What does blood smell like? Not Christ’s, not Buddha’s, but mine–a small man whose name only recalled the name god who was supposed to take care of his universe from his supine half-sleep from under the cool, sea-scented, consort-supported peace of a multi-hooded shade of a giant serpent’s unmovingly faithful pose. I thought the oceanic god must know. The smell. Could it be like the smell of the sea at Puri? Or the same sea at Konarak, which had taken in the little boy of my younger son’s age, who is believed to have been able to fix, under a dream-accomplishing divine guidance, the last, small, but defeatingly impossible piece of red sandstone on the top of the temple of the Sun-god, beside the sea at Konarak?

Dharmapada, that was his name—the Buddhist name of the child of a Hindu temple’s Hindu Chief Sculptor whose master, the King, had haughtily declared to himself that he was about to complete the most splendidly raised temple dedicated to a Hindu god whose kindness and generosity had cured the rough, muted disease of the erratic son of the same oceanic god who was supposed to sustain the universe. A temple that would stay on, defying time and the all-corroding, all-year-long saline touch that accompanied the sea breeze that kept arriving from beyond the distant, lonely, far-eastern islands of Java and Sumatra.

Dharmapada. The legendary child-hero whose nimble fingers alone were capable of completing the Sun Temple at Konarak. What colour was his blood? The same as mine? Emerald green? Like the sea’s? Or red? Like the sandstone’s? About a year ago, someone had even threatened that residual knowledge of physics that I thought had stayed with me all the way since my age was seventeen and studied the chemistry and physics of the sea and the sky, by challenging my dream of the emerald sea. “Sea is not green, nor blue either, nor even gray,” he maintained and laughed at my ignorance of commonplace things. “The sky is neither blue nor light-blue nor red. The sea and the sky are colourless, like water and air.” I had my doubts and faith. For me the sea changed its colour with its changing moods, just as the sky did with its own.

Again, like blood. Slow blood, just an ounce of slow blood, crafted out from a vein for confirmation of a healthy life, by a pine-leaf-like needle by deft, delicate fingers. Fast blood, like what flows inside those little, boasting, frolicking girls and boys over the small grass of a field effortlessly open to the sky, or like the old British Romantic beside the tossing and turning daffodils fringing a British lake. Angry blood, with the cold, knife-twisted, jet-like shine of inner flesh. Soft blood, like a newborn angel’s. And of course the just, the righteous, much-in-demand blood, quite like mine this morning, strictly following some unseen and unknown method and line and perhaps as a sort of compensation for a wrong done or only mistakenly, inadvertently, contemplated through the future.

******

Bibhu Padhi, a two times Pushcart nominee, has published seventeen books of poetry. His poems have appeared in magazines throughout the English-speaking world, such as Contemporary Review, London Magazine, Poetry Review, Poetry Wales, Wasafiri, American Scholar, Poet Lore, Poetry Magazine, Southwest Review, TriQuarterly, Antigonish Review, Dalhousie Review, Queen's Quarterly, and Indian Literature. They have been included in numerous anthologies and textbooks. He lives with his family in Bhubaneswar, India.

Beautiful!