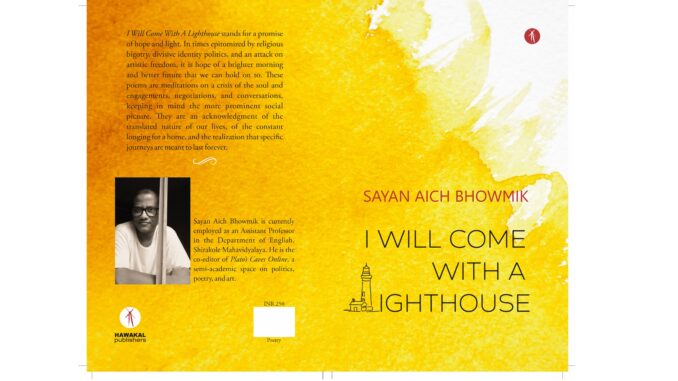

I Will Come With a Lighthouse by Sayan Aich Bhowmik. Hawakal Publishers. 15 January 2022. 64 pages

Bhaswati Ghosh

Between Letting go and Holding On!

E

ven though the forty poems in Sayan Aich Bhowmik’s debut poetry collection are divided into four themed sections, the title of the first section — Longing and Solitude — sets the motif that will pattern itself throughout the book. Bhowmik’s attention, marked by an aesthetic of dewdrop gentleness, often turns to absences — of people, places, memories and even a self in search of its own skin. An undercurrent of tension — between letting go and wanting to hold on — runs through the poems like mercury inching up a thermometer.

The opening poem, The Moth, not part of the themed sections, contemplates two cities that live in one — as Calcutta and Kolkata — and of available pin codes sitting with missing story-tellers. This sense of loss and its ensuant seeking is the vein that throbs through the poems. In When We Meet, Bhowmik says, In this town / strangers come / leaving a bit of themselves / pinned on the mists / the hills wear / as Kashmiri pashmina.// Some stay back/ ploughing the air, / with long distance phone calls / to people, whose names / have disappeared / from telephone directories.

Bhowmik’s imagination is wide and accommodating, which makes his canvas luminous with unexpected and startling visual abstractions. Here, the mind can oscillate between two thoughts before finding one of those / park benches between them / a really drunk night / would have walked onto the stage / with dead stars / on its lapel. (Certainty)

If loss is the dominant note that resonates through the score of I Will Come with a Lighthouse, Bhowmik ensures that it remains a soft one — played with sensuous restraint, not screeching precipitance. He draws our attention to the very act of being attentive, with our immediate senses, and also to the deeper terrains those sensory pointers lead us to. By doing so, one can look at even sadness from a distance, a place where in spite of pain, a certain dignified calm imbues one’s sensibilities. Consider these lines from Men From Salamanca: The men have left with their shadows / only that sad light from the stars / keeps dripping.

I read I Will Come with a Lighthouse chronologically. When I looked back at the second section, On Love, I couldn’t help but notice the sequence of the poems — First Time, Folded Sky, Somewhere Else, Elsewhere, Of Previous Births, The Last Pages, Of Things Like The Sky, Nine Lives or So, 711 Windows, Fever. The very arrangement of the poems seemed like a garland that had every flower picked and placed with thoughtful affection. Again, the sting of loss is sharply present here, and Bhowmik tells us that love is but another name for longing, not only for what is lost, but perhaps for what is eternally elusive and beyond reach. In First Time, the opening poem in this section, he says, in one long, unpunctuated sentence: Across that long courtyard / where I once sat / eating pistachios and drinking tea / your ghost talks with mine / in a tongue / which turns words into air / the kind which remains / between lips / meeting for the first time.

What shines through all the heartbreak and despondency that love leaves in its wake is a mature, near-stoic equipoise Bhowmik’s poetic voice is able to redeem. In Elsewhere, the poem from which the book’s title manifestly gets its name, we see these lines, You have uprooted every milestone / and brought down every lighthouse / that could have led me to you…only to be followed by I have realised that / even though the highway and the winter /might return / they will now take me somewhere else.

Bhowmik’s love poems capture with unstained candour, the discoveries lovers make as they explore each other’s deeper selves through the physical realm. The best of these immerse the reader into the mystery of such discovery, into that subterranean space that germinates poetry. Is it possible then / that the moment you undress / the tungsten bulb melts / on your moonlight skin. / A country in exile / dreams in the language of return / where everyone looks / like everyone else (Of Previous Births).

The eight political poems in I Will Come with A Lighthouse are all derived from the severe traumas and fissures the Indian subcontinent has experienced in its relatively young postcolonial life. Dhaka, the first poem in this section, speaks of a grandmother’s need to keep the history of her home alive by recounting stories about her life in undivided Bengal. She sprinkled a fistful of the Dhaka rains / onto the portions she felt needed / a little more care, Bhowmik says of this act of storytelling, and then, she would smile at the Sylhette moon / always an hour and a half here and there / compared to the one in Calcutta, / and say, “Some yarns were sharper than knives.”

Kashmir is on the poet’s mind, too, and in a poem of the same name, while considering the epithet “heaven on earth,” cherished yet incongruous following decades of conflict in the region, Bhowmik says, But in the heaven / that is not on any tourist brochure / tombstones have names. He writes about the delusional aftereffects of war in In Dreams and in Mapping Blood, feels the stickiness of blood still smearing the pages of an imaginary atlas in which he traces his own history in cities like Lahore, Delhi and Dhaka. That this enduring pain and violence that the partiion of India has bequeathed to its three offsprings — India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh — continues to haunt the psyche of successive generations is starkly evident in Bhowmik’s political poems.

Even a cursory reading of Bhowmik’s poems reveals his commitment to craftsmanship. The economy of his words, the delicate care with which words are sewn into lines, the self-reflective glance into the poetic process — all these bespeak his interest in being a student of the craft as much as a practitioner of the same. It doesn’t surprise then, that there’s an entire section titled On Writing in this collection. Once in a while / if you ask a poem / it will choose a language and dialect / for itself, Bhowmik says in Choices, the opening poem in the section. This willingness, curiosity even, to listen and imbibe isn’t limited to the poet’s intuition.

In Twin Cities, he invokes two of the subcontinent’s most celebrated and loved poets, Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Agha Shahid Ali, in such affectionate terms — I switch between two languages / when writing about you / between Faiz and Shahid / between nights descending on Lahore / and evenings on grocery shops in my neighbourhood — as if he were talking about family members. He goes so far as to imagine Agha Shahid Ali disapproving of his verse and jeering at his moon (Witness). In Separation, Bhowmik returns to the difficulty of deciphering a language like memory. Memory is a foreign tongue / rusting on spiral staircases / that go all the way / to the moon, he says. The poem’s final lines, striking in their ability to underscore the fragility of memory — At the end, all that remains / is the breath between / a word and it’s forgotten meaning — strangely reminded me of something I’d heard my brother say about the sudden passing away of a loved one — that the one thing that haunts those who are left behind is the sorrow of “not being able to share the full story with the departed one.”

I Will Come With a Lighthouse is a slim volume; slim but not light. The verses carry many kinds of weights — personal, political, generational. Yet, it’s not a weight that pulls one down. It’s one that makes the reader measure the scope of loss with ruminative deliberation. One is left feeling the ache of the unfinished business Bhowmik alludes to time and again.

And one is found seeking more of Bhomik’s words to heal that ache.

Savour these from I Will Come With a Lighthouse

Dhaka

I

There have been evenings

when my grandmother would weave stories

from the pashmina threads of memory.

She would seamlessly arrange all the events

which by then I knew by heart

and she would keep weaving

long narrow, now foreign lanes

which ran like mice throughout the fabric.

She sprinkled a fistful of the Dhaka rains

onto the portions she felt needed

a little more care.

Soft summer evenings would creep into her eyes

taking her to a courtyard

where at first was planted lilies

and then children who couldn’t escape the partition.

When I asked her if all this was true

that women were raped, killed and raped again

that men lost their manhood

before they lost their lives

she would smile at the Sylhette moon

always an hour and a half here and there

compared to the one in Calcutta,

and say, “Some yarns were sharper than knives.”

Kashmir

II

Here I am

writing about my favourite hell

holding a tourist brochure in hand

wondering at the delusion

that proclaims, “Welcome to heaven on Earth.”

But in the heaven

that is not on any tourist brochure

tombstones have names.

Pakistans and Hindustans

The ants on my wall

form a long procession from opposite sides

meeting and greeting each other

sometimes a warm hug, maybe a kind word,

then are on their way.

My grandmother, when alive,

would have hoped people migrated like that

to their Pakistans

to their Hindustans.

Twin Cities

I switch between two languages

when writing about you

between Faiz and Shahid

between nights descending on Lahore

and evenings on grocery shops in my neighbourhood.

I slice open with words

dark nights, and paint brush them

over your city and mine

sprinkling Urdu between the stars.

I switch between two selves

when writing about you

one watching the river go by in Banaras

the other burning in Kashmir.

*********

Sayan Aich Bhowmik is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English, Shirakole Mahavidyalaya. Kolkata, West Bengal. He is the co-editor of Plato's Caves Online, a semi-academic space on politics, poetry, and art.

Bhaswati Ghosh writes and translates fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Her first book of fiction is 'Victory Colony, 1950'. Her first work of translation from Bengali into English is 'My Days with Ramkinkar Baij'. Bhaswati’s writing has appeared in several literary journals, including Scroll, The Wire, Literary Shanghai, Cargo Literary, Pithead Chapel, Warscapes, and The Maynard. Bhaswati lives in Ontario, Canada and is an editor with The Woman Inc. She is currently working on a nonfiction book on New Delhi, India. Visit her at https://bhaswatighosh.com/

Bhaswati Ghosh in The Beacon

Leave a Reply