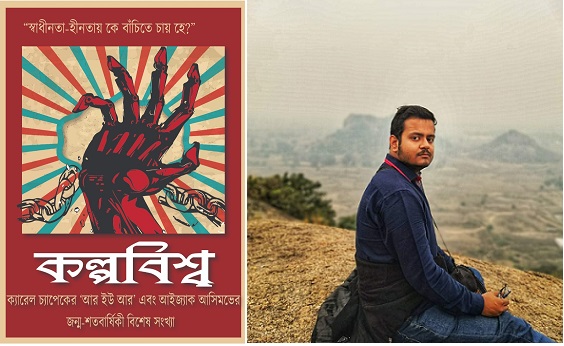

Tarun K. Saint with Soham Guha

Tarun K. Saint: Welcome to this session of South Asian SF Dialogues! As an active participant and member of Kalpabiswa, the Bengali language SF collective, what is your assessment of the SF scene in Bengali today? Is contemporary SF from West and east Bengal still somewhat in the shadow of giants like Premendra Mitra, Adrish Bardhan and Satyajit Ray, or has a new idiom evolved recently, moving beyond the adventure tale, the didactic and whimsical variants?

Soham Guha: The heritage of SF in Bengal, both east and West, is rich, distinct, yet somewhat underrepresented to the global audience. Looking at the current status, the development may appear fragmented, even halted. The reason can be traced to the mainstream vernacular magazines, the respective publishing houses, and their treatment of SF entirely as MG fiction. Magazines play a crucial role in the emergence of genre fiction, as they are the first and foremost platforms for any aspiring and experimenting pen. However, looking at the SFs printed in these magazines, if someone compares them with the global standard, one might find the majority of the stories to be inadequate antiquities. Considering the lack of SF special issues, the reluctance to experimentation, the predominant absence of adult themes in the printed SFs, the prevalent atmosphere can be said to be stagnant. This is a stark divergence from the paths paved by SF-only magazines like Ashchorjo, Bismoy, and Fantastic. All three magazines were either edited or influenced by Adrish Bardhan.

This can be considered as the shadow cast by the giants. Their popularity, particularly of Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonku, had given birth to many feeble attempts at imitated storytelling. It is my ignorance that I am yet to read any recent SF from Bangladesh. The only works I have read are from Muhammed Zafar Iqbal and Humayun Ahmed. So my opinions are based on what I read from West Bengal.

At the other end of the spectrum, is Kalpabiswa. In its very execution, since its formation, this webzine has been an ambitious and courageous platform. It was where my first story found a place. It is the reason I continue to hone my craft. Away from the shadow of the giants, from the normalized practice of representing SF as children’s tales or an offshoot of mythology, Kalpabiswa is not only standing against the majoritarian tide, but paving its way. The stories I read there, and try to write myself, are about the socio-economic, political, ecological, psychological crises of our civilization. The reemergence of Kalpavigyan, in my humble and optimistic opinion, has already begun.

TKS: As an extension, how important is such a lineage of SF writing, reaching back to the nineteenth century, for you personally?

SG: History, despite its receding properties, is an integral medium for understanding origins, evolutions, and prospects. Jagadananda Roy and Jagdish Chandra Bose wrote the first works of Bengali SF in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Masters like Premendra Mitra, Jagadananda Ray, Satyajit Ray, Begam Rokeya, Adrish Bardhan, Ranen Ghosh, and Anish Deb left their seminal footprints in this genre. Their works, particularly Premendra Mitra’s understated novel সূর্য যেখানে নীল (The World under An Azure Sun), compelled me to look at the sky and think about the fragility of our Pale Blue Dot. It amazes me to think that we are a species restricted in the cradle of their home planet, with a possibility of being a star-faring civilization. If that is too ambiguous a dream controlled by our extinction-agendas, someone – not us but our children – will surely leave footsteps on the exoplanetary sod and soil orbiting Proxima. That is the role SF plays. It makes these futuristic dreams a possible probability.

The only way Kalpavigyan, or any genre, can evolve, is by looking back and learn from its past achievements, and mistakes. Bengali literature, and Indian in the broader sense, because of our rich cultural heritage, is diverse and multilateral. There’s much to inherit and adapt, and plethoric ways to develop. SF writing in this subcontinent has a tremendous potential to grow, given the right audience, writers, critics, and publishers.

TKS: Which SF writers left a key imprint on your writing style? Did writers in the Anglo-American tradition (Asimov and other Golden Age greats, or even more recent SF) have greater importance, or was it the East European and Soviet writers like Stanislaw Lem and the Strugatsky brothers? What about sub-continental epics, mythology and regional SF?

SG: The work that inspired me first was Adrish Bardhan’s (He coined the term for Bengali SF – Kalpavigyan) enchanting translations of Jules Verne. I wear spectacles now because of my childhood fixation on finishing a book in one sitting; often reading by flashlight! Verne ignited the first sparks when I was only eight. I still have some horrendous fiction – poor imitations of both Ghanada and Professor Shonku – in my cupboard (skeletons?) that I wrote during my early teen years.

I started reading English SF only five years ago. At the second-hand market of College Street, as it became my regular pilgrimage during the graduation days, I found someone had dumped his/her late father’s entire library. Among them, there were fifty-two SF books from various authors of the golden age.

There was something strange about the books. Perhaps it was a combination of the fascinating blurbs on the back cover, the unfamiliar front cover illustrations; I bought all of them impulsively. Though each book was only fifty rupees, it was enough to empty my purse.

Then I had to carry the entire collection on my aching back.

The first book I fished out from the bundle was Childhood’s End, a Pan first edition. Looking back, I now understand this masterwork has the immense potential to immerse any first-time reader into the uncanny worlds of SF. Clarke’s masterful prose, the novel’s multilayered characters, the philosophical dimension, and vivid imagination of the final days of humankind, gave me a glimpse of an infinite frontier. Later Olaf Stapledon broadened the frontier even more.

Because of my voracious reading habit, and an abundance of second-hand books, though many authors left their impressions on me, nothing was as profound as Childhood’s End.

Unfortunately, I am yet to venture into the worlds of Lem.

Contemporary SF authors like N.K. Jemisin, Cixin Liu, Samit Basu, Indra Das, Stephen Baxter, Sue Barke, Ken Liu, P. Djèlí Clark, and Neal Stephenson’s slipstream and SF works leave me with a sense of awe and inspiration.

Every Indian child learns about the epics from their grandparents. My grandmother, alongside these epics, also orated Thakurmar Jhuli (Folklores from Bengal) to me. I believe the first stories we hear inherently play a role in our upbringing. Stories like these broaden our imagination, shape our physiological landscape, force us to think outside the box, and make us humble.

TKS: As a bilingual writer and critic, do you think enough translation is taking place across languages, or does a language hierarchy still prevent adequate cross-cultural dialogue in the domain of genre fiction?

SG: There’s not enough SF at present in translation either from English to the vernacular tongue or vice versa. I presume this is particularly so because our country is home to languages of diverse ancestries. Many vernacular writers had written spectacular examples of SFs in their mother tongues.

However, as English has become a more common conversation tool with the rise of technology –with the availability of the internet and smartphones – translated fictions now have the potential to reach a vaster audience and make them aware of these hidden literary treasures. Translated SF fiction in India is now a growing market. Works by Arunava Sinha, The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction and It Happened Tomorrow are its prime examples.

TKS: Give us a sense of the role of Kalpabiswa in sustaining the Bengali language SF culture.

SG: The journey of Kalpabiswa, for me, is very personal and inspiring. If there was no Kalpabiswa to give me the arena for my first story, and the support in later years, I can surely say I would not have had the courage, or the audacity, to write further. I wasn’t around when it was born with the blessings of Adrish Bardhan. But I have seen it grow from a mere endeavor of some SF enthusiasts, who felt the void left by Bardhan’s last SF magazine Fantastic and the indifferent treatment of SF by the mainstream magazines, enough to being the only regular SF magazine created and curated for Bengali readers. The editors Dip Ghosh and Santu Bag, inspired by the Year’s Best Anthologies of the west, brought out their own Year’s Best – Sera Kalpabiswa. Under the guidance of Late Ranen Ghosh, they also formed Kalpabiswa Publication, a publishing house solely invested in SF. The publishing house is now getting ready to set sail on bilingual waters.

Kalpabiswa Publication is not only introducing new authors but also reprinting some of the lost classics of Bengali SF. The translated works of Adrish Bardhan, original fictions by Siddhartha Ghosh, Ranen Ghosh, and Rebanta Goswami, collaborative shared-universe works like ‘Sabuj Manus’ (‘The Green Men’), much of which was out of print for some decades, have found a home in Kalpabiswa.

They also published the first Bengali ebooks available for Kindle: a daunting endeavor in a congested market with archaic practices.

With each issue, particularly with the Saradiya (the annuals), Kalpabiswa presents fresh pens to the readers who, thanks to the magazine being a webzine, are spread across the world. The quarterly issues are dedicated to a particular subgenre of SF while the Saradiya, because of its massive volume, has no particular theme.

I was grateful to be a part of the two-day seminar they orchestrated with the help of Jadavpur University. I had the chance to meet authors like Samit Basu and Indra Das, critic Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, and editor Salik Shah. It was perhaps the first SF seminar in eastern India. The seminar encouraged me to attempt writing in English.

TKS: Your forthcoming story ‘Song of Ice’ (in translation by Arunava Sinha in the Gollancz Book of South Asian SF Volume 2) is in the line of dystopian writing about the looming threat of climate change. Share some details about the genesis of this story based in the Calcutta of the future, ravaged by cataclysmic changes to the ecological basis for survival leading to extreme behavioral transformation and the breakdown of community.

SG: Since I live on the other side of Ganga, in the Hooghly suburbs, I did not, and still don’t, avail the metro often.

In 2017, I was a freshman in college and desired to explore the City of Joy. The day I first boarded the subterranean train was the day the metro malfunctioned and abruptly stopped on the track. There was smoke, there were screams, there was darkness. It took the officials sixteen minutes to reach the immobilized train. During these minutes, sandwiched between terrified men and women, profusely sweating, suffocating, my tongue was like sandpaper, doused in claustrophobia. All this, trapped in the belly of hollow concrete worms was an alien experience. When I came above ground and my hands stopped shaking, I asked myself, what happens if we are forced to live here? What happens if this asphyxiating place becomes the last frontier of our kind? These questions evolved into ‘Song of Ice’.

TKS: ‘Song of Ice’ is rooted in an understanding of a long history of conflict and socio-political movements, dating back to the freedom struggle, also including the 1960s student protest movements with their stirring idealism. Yet there is also a sense of melancholy at the falling off from such high ideals and values. Is there a conscious attempt here to achieve an ‘estranged’ or distanced commentary on the present in your depiction of the grim future to come?

SG: On both my parents’ side, there are stories of migration, separation, financial instability, and melancholy. My roots were in Barishal, a part of Bangladesh. Partition has left for us a coffer full of stories, for stories were never short among those who crossed the Radcliffe Line. This very word is the embodiment of division, displacement, and refuge on an unprecedent scale. People who were brothers, neighbors, overnight became invaders, even aliens to each other. The wake of partition is still prominent, though seventy-five years of independence made it more subtle with each generation. The seed of the student movement, of which my father was a participant, can be traced back to Partition, to the Raj. Hearing these stories from my father, my Khuku Pisi (paternal aunt) who was on the last train from East Pakistan, made me aware of what we lost, and what we can gain. We are fragmented, too muddled among ourselves to be one. We are a species thriving on entropy. On this note, Emerson’s ‘We don’t inherit the Earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children’ becomes an apt phrase about our responsibilities for our world and society. Perhaps it will be the final days of my generation, or our children’s, that will inherit a fragile, dying world battered by erratic climate, exhausted resources, and poisoned surroundings. We are entering the third panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, a world running on fumes. Because of this, what we do today, how we change the present will assure this grim future never comes to fruition. History is a riverine system of interconnected channels. Every minute change of thread in this grandly woven tapestry creates another possibility.

To understand where we stand and what we can become, we must reflect on ourselves; that is where the moral obligations, our values, and ideals become important, if not integral. All these played a subconscious role when I was writing this story. So, though it was not deliberate, the distanced commentary is present.

TKS: You have expanded the story into a full-length novel in English titled Frostsong (yet to be published). What were the challenges of extending the initial storyline into the different format of the novel, especially in terms of world-building?

SG: The idea of Frostsong bloomed in me when I was in college. However, because of my circumstances, and I did not have the experience then, I could not write it even though I wanted to. Because of this, the novel (and the series) remained scribbles in my notebook for long, as plot points that span across the entire timeline of our universe. My aching fingers drove me to put down a part of the novel as a story. And now, slowly climbing the learning curve, I attempted to write it down because I was yearning to bring these characters, their motivations, inter and inner conflicts into life, and give the world of Frostsong the complexity it deserves. Frostsong, because it is a post-apocalyptic novel where the climate becomes too savage too sudden, acts as a flocculant mirror of our extant society. It is about the monsters inside us, the monsters that are outside, and the people torn between humanity and animalistic insensitivity. Time and again history has shown us the fiends it gives birth to when survival becomes the driving force. Frostsong is a story of India, of its people, trapped in a world of ice.

TKS: And work in progress, any other forthcoming books and stories in the SF vein

I am finalizing the draft of Frostsong. I am looking for representation and writing other short stories sailing on the speculative stream.

TKS: Has contemporary SF/speculative fiction, including your work, become a vehicle for more sharply critical statements about present day dilemmas, whether in the domain of religion, ecology, gender relations or politics, eluding the traps of informal and formal censorship in the process?

SG: Because of the sheer potential of SF, and because the authors derive the inspirations for their work from reality, SF becomes a metaphorical vessel of diverse narratives. When we read stories set in our current world, and see characters interacting with contemporary settings and themes, involuntarily we try to relate with the scene. This way, the reader’s opinion, because of her/his preexisting experiences, becomes biased. SF isolates readers from this sense of associating as it takes readers to unfamiliar locations, on a secondary world. Here, because of this unfamiliarity, and the unexplored possibilities, even if the problems presented are derived from our world, the reader can attend to them in a more detached fashion, not as an interpolated character, but as a keen observer. The interpretations drop their abstruse veils.

Particularly contemporary SF, as representation from the marginalized sections around the world emerge, open a doorway to stories that dwell in multidimensional, multicultural, multiethnic, and pluralistic concepts. The jagged narratives courageously criticize these issues without the presence of the hegemonistic censorships (often) because most of the stories are of an alternate or future world. Contemporary SF narratives, in their subtle yet glaring execution, are stories of our wounded world and how we can heal it, and ourselves.

**

![]()

OUR LIVES ON TIDES

Soham Guha

We all dream of flying.

I’m living that dream now, like Icarus, seeing the world from here, asleep almost nine thousand kilometers beneath me. The first golden rays of the sun touch my face through the visor and illuminate the floating castle of ice beneath me like a gargantuan unpolished diamond. The earth below me is dark in the final hour of the night: a global ocean wraps the planet in her cold watery embrace.

Amidst the perpetual darkness, I count eight bright dots. Eight illuminating sites of civilization. One of them is my home, Kolkata. It propels its behemoth self across the ocean; and deep beneath, in the city’s steel and titanium womb, eight hydraulic engines make their noise, and enormous blades generate electricity from the ocean currents. Were I there, I could hear the sonnet of the city, sung in low vibrating whirls and thumps, like the pumping heart of this metal Atlas.

The transmitter becomes alive in my helmet, with a voice I can recognize amidst the commotion of a crowd.

“Mission Control to Messiah 2, did you establish touchdown?” you ask. If I had the sight of a thousand falcons, I could see you right now.

For a moment I forget my zero-gravity situation, and nausea and mild vertigo I’m facing, and my eyes move towards the tropical thunderstorm raging in the south. “This is M2 to MC. There is touchdown. I’m on XF2. Now about to set the charges,” I say.

You answer worriedly, “Godspeed.”

Although there is the whole atmosphere between us, I can picture you, my love. You are sitting on a plastic chair. The monitor is showing you my vital signs, the oxygen left in my tank, the distance between me and the ship, and maybe a photo of mine is minimized somewhere between all this. Maybe you are having some trouble breathing; maybe you fumble your hair as every second stretches longer than you anticipate.

I remember how you reacted when you came to know that I was involuntarily selected. You threw a glass to the wall. You believe yourself to be a piece of helpless machinery in this system.

Speaking of machinery, do you know Kolkata, our floating metropolis, looks like a firefly from here? Seeing it, I can feel how small we are, how insignificant are our contributions in the pages of history.

History is all we took with us when we fled.

#

Do you remember the day we met? There was a collaborative conducted tour in the artificial wetlands adjacent to the city. Outside Kolkata’s circular four-kilometer radii, they had made the wetland farms.

The guide was a novice and failed to answer how the seawater was treated with bacteria, how the defecated matter from the city were used as manure, or how the vegetables grew so big in those hanging gardens. While the instructor scratched his head, you stepped in beside me and said, “Arun Roy. Nice to meet you. Don’t give him a hard time. If you can come with me for a drink, I can answer a few.”

I knew the answers, I only asked to pull legs. Even before you took me to the bar, the way you moved, gestured, the way your eyes danced, I could tell that you were like me. But I could not ask first, I dared not to. And yet I accompanied you to an underwater bar. The place was beyond my reach. You had a permanent tab there. A school of salmon swam before our window; you rested a hand on my thigh and asked my name. I moved your hand, worried in case someone noticed it. What if I was wrong? After all, the government prohibits same-sex relationships to keep a viable fertile population. They even set drastic examples for those who protested.

You did not care. You were searching for someone just like me. We were searching for someone like us.

I remember the way you made love to me that night when I sneaked you in my apartment through the fire escape. You held me like a blossomed lily and caressed me like a caring gardener. It was my first time with a man, my first time with anyone. My circumcision astounded you; it was necessary in our religion for purification. Your religion did not bother. It hurt more than I anticipated but you whispered in my ear that all will be well. You made me an addict of the coffee you made, first thing in the morning. Moored and hypnotized, I sunk with you. I started to fall in love with you.

The government continued to show their propaganda against us. On the television; everywhere.

The day when I found that I was going to space, you grabbed me on the shoulders and I saw terror for the first time in your eyes. You asked, “Do you even know why you are going up there?”

I had a vague idea.

“Remember what we read in school?” you said. “Fifty years ago, Hailey’s Comet struck the moon and scattered into a million pieces. It came back from the Kuiper Belt being ten times larger than the scientists anticipated and a full year later. The experts thought it merged with some other comet or might have become a part of it.”

I know. The pieces were attracted by the earth’s gravity and our pale blue dot resembled Saturn for a decade. The Kessler Syndrome acted on the smaller pieces of the accretion disk. They came down as rain. Endless rain.

It was called the half-centurion monsoon because the rain came to the Indian subcontinent, and all over the world, in the winter, and never stopped for the next forty-five years. The water rose to a colossal fourteen thousand feet before the sky finally cleared. Our parents and grandparents worked against the rising tides and the endless rains on the roof of the earth. Their generations hollowed the earth’s crust for raw materials, excavated deep within her subterranean womb to create the final arks. They followed in Noah’s footsteps, knowing the waters would not recede. They built Kolkata and her thirty-three sisters before Lasa, the last terrain city, sank; and now we roam alone. While every generation borrows the earth from their children, we are indebted to our ancestors. Without them, the last billion of us would have been impossible. Though now when I think of it, I wonder if we even deserve this gift. This is not the world they envisioned.

“But the thirteen biggest pieces are still up there,” you said. “If they come down, we’re fucked. That’s why we keep going.”

I know. I detach the cable that connects me with the spaceship and hook a new one on the iceberg. The circle of illumination is stretching its periphery below me. Dawn has come in the world and people are waking from sleep unknowing what danger looms above them. I once was one of them: ignorant, self-absorbed, and blind. You should not have barged in my life like it was your playground and made me so aware of my surroundings.

Arun, before you came, I did not know what it meant to be loved. I forgot how it felt. You cannot grasp what an empty house means to you, or an empty bank account. After all, you are the son of the defense minister, you always have what you want. You will now protest, saying that your paternal connection to the government made you aware of its delicate clockworks, and I believe you are right. We often argued about it; I remember one day in particular.

It was a winter evening and I made rice and fish curry for us. The stars and the broken moon were visible through the transparent plexiglass dome above and their lights came down on our balcony. The pedestrians moved beneath, on the motorized footpath that originated from the city’s center and stretched inside it like interconnecting threads of a spider’s web. You took a spoonful and commented bluntly, “Look at them. So happy. So oblivious. Is this even living?”

My spoon stopped right before my lips. “I don’t understand. What do you mean?”

You had visited your father earlier that day and I wondered if something happened between you two. After your mother’s death, the glue that stuck you two together had dissolved in grief.

You told me once that melancholy has the taste of the sea.

“They went through a trading dispute with Delhi. I mean, if trades stop, how can we even sustain ourselves throughout the summer? We need fresh soil from Himalaya for the farms.”

“Why do you keep worrying about things that don’t concern you? It’s your father’s colleagues’ duty to resolve the matter. Not yours. Even though you are a government employee, you are an astrophysical surveyor, not a minister. Look at the stars, not the earth.”

“I wish I could continue to do that,” you pointed at the multistoried buildings and the roads before us, “If I could forget their existences.”

When I looked where your spoon pointed, I noticed the security cameras. The cameras envelop the city like a digital invisible umbrella. “They are watching us,” you said.

The city is a floating device with limited resources, drifting in an endless ocean. They are right to worry about peace. However, during implementation, they forgot that peace always comes at a cost. Sometimes the cost is freedom, sometimes it is individuality. The city is our refuge, our hope, but it is also our prison. I knew about the gay couples who were thrown out in the sea after they were found out. I never asked how the government knew where to look.They were looking always, looking everywhere. We are the Mynas who live in a birdcage because there is no more jungle left to roam. We are the silverfishes who devour book after book in a helpless rage because we cannot write a single word for ourselves.

“If you are so angry with the government,” I asked, “Why are you its employee? Hypocrite!”

You pointed the spoon at your stomach. “Revolution never happens with an empty belly.”

Our walls shook for a second:the city’s heart skipped a beat. You looked worried. “The city’s breaking down, both physically and institutionally.”

You told me that there was once a democracy completely different than what we have right now: that it was us who chose the ministers, not the members of the one-party government. I guess they introduced this system to cut down expenditure and increase political stability. “What do you mean?”

“The engines, the storage rooms, the prison, and the archive beneath us creates a good ballast of weight for the city. It keeps the city stable above the waves. But rust and corrosion have taken place. The government knows about this, but they are too busy with low-hanging fruit. It feels like they are cutting the very tree where their treehouse is.”

“Are you talking about Kolkata or all cities in general?”

“I know it is definitely true for Kolkata. I think it is the same for the other cities. The sea is a merciless landlady. We are living in her, and the rent is long due.”

I looked at the anadromous fish I served as the side dish. Whenever I taste this fish – Hilsa, cooked with mustard and spices – I savor the flavor with the tiniest of bites. Our Bengali roots, our genetic and cultural heritage, were evident in the plates. When I look back at history, particularly the years of our riots and partition, I wonder, while we share the same mother tongue, the same national anthem, almost the same taste for food, why do our religious beliefs have to be so different? And why does the government encourage religious separation?

I asked, “Why is our home breaking apart, Arun?”

Maybe it was written on my face; you said, “Because our refuge isn’t sustainable anymore. The government, like the colonial British preceding them, believes in divide and rule, to ensure harmony. Yea, when you say that aloud, it does sound oxymoronic. And you somehow think astronaut training will help us.”

You laughed. I laughed too, uneasy.

It was my ‘Father-In-law’ who gave the speech that sent me up here. “Recruits,” he said, “you are gathered here today to serve your states, for there is a portentous matter at hand.” He switched on the screen behind him. “As you can see, there are thirteen floating icebergs above us above, hanging like motionless pendulums of a dysfunctional clock.” Then he looked at me and said, “Recruit Imran Mandal, this is for you,” and enlarged a single XF on the screen, “This is XF2. It is above Kolkata. XF2’s orbit is decaying. All XF orbits are. Enormous bodies like these create drag and that drag will soon decentralize their orbit… that’s where you all come in.” He shifted to the next slide to conclude. My heart almost stopped when I saw it. It showed the XFs crashing on earth. The shockwaves would be absorbed by the water; there would be no earthquake. Instead, they would converge, and a mega tsunami would ravage the last strands of human settlement.

We are planting bombs in space to save humanity.

#

Now I encircle the iceberg and drill in the specified places and create a path resembling an armillary sphere. I put in the required blocks of charges there (as mentioned in the briefing file).

From here, the green peaks of Himalaya are visible as a chain of small islands and all I can see is the airtight glass jar I left in the almirah.

My mother, I told you before, was a nurse in the city hospital. She was pregnant with me when they boarded her on the refugee ship from Lasa. Not much she carried but one of them was a jar.

I became an orphan just before I reached my twentieth summer.

I will always remember the day they handed me my ma’s belongings. There was nothing much, small enough to fit in a briefcase. A civil servant came in and looked at my bloodshot eyes. Tears had left their dried marks on my cheek. I still was having trouble breathing, as if the walls around me had closed in and converged to create a prison cell. I wanted to wrap myself in those barren bricks of memories and put a ‘do not disturb’ sign on my door. It was the least I could do.

I could not remember how long I held the last clothes she wore; I only knew the shadow of the buildings grew larger on my floor and then disappeared, the shadows turned into darkness and the streetlights failed to create a milieu in the absence of daylight.

In the dark, I fumbled through contents of the briefcase until a jar caught my hand. I switched on the lights: it was a sealed jar with dirt inside. I was young and did not grasp what it meant. I was born in the sea, without a memory of what the world was before. The only things I saw in my life were an endless ocean, the highest peaks of Himalaya, still standing with their skyscraping pride, the cities that float on water, all underwater farms and attached fisheries, and the thunderclouds.

But now, as I look at the Earth, I can feel my heart breaking apart because I finally understand what it meant for her. Now I know why my mother treasured it like jewels for her whole life. The dirt inside the last fragment of her submerged home, the last page of her father’s memoir in a transformed water-world. She told that my father died in the flood, that the rising sea claimed what was never hers. Somehow, I found that hard to believe. Maybe because he survived only in her memories, not in photographs. She is now gone with the rain, and there are no more memories left as his anchor on this planet.

The sea has breached my suit through my eyes; droplets of salt water are floating inside my helmet.

#

I told you once about my recurring dreams about the Kolkata that existed before my lifetime, the Kolkata that came alive in my childhood bedtime stories; you only nodded in response. I wanted to see the city my ancestors called home. I wanted to feel their imprints in my life.

Now nothing is left there apart from the highest peaks; it’s a blank slate. I look at the present Kolkata. It shines like a crystal as the newborn day places its lights on its metal physique.

“How the universe looks from Jannat, Dr. Imran Mandal?” The transmitter barked in my ear. You used my term for heaven. You only used the word when I orgasmed. “It is heaven out here, Mr. Arun Roy. It looks like there are diamonds all around me stitched on black fabric.”

Though the deadline is closing in, I feel surprisingly calm. There is no sound of detonation in space, but through my visor I see that others of the Messiah Project have finished their jobs. The exosphere around me bursts with the bright blue, yellow, orange, and green explosions of ignited Dipicramide and Hexanitrostilbene as the other XFs shatter into a million pieces. I am now behind schedule, but I stop drilling and observe the fireworks.

As I look at the world down beneath, a spark of hope lingers in me. My whole life, like the lives of other citizens, is shaped by the city. In ancient China, they practiced foot binding; I feel I can somewhat relate with the girls who suffered. When someone takes away your ability to walk, to talk, and to love freely, how can someone express themselves to be alive anymore? We are pets in the zoos Mother Nature forced us to create. But here I can think about it freely. Their laws and regulations don’t work in space. Even the strongest of iron fists loses its grip.

As I finish planting the last Flexible Linear Shaped Charges (FLSCs), and declare it to you, you say with joy, “Open the left pouch on your suit.”

I unzip the pouch. There are two pockets in it. You whisper in the transmitter, “Something for you, my friend. Happy birthday in space.”

It’s a holographic projector. With the whole earth as a witness before me, I press the only button on its surface. It blooms like a hibiscus and a three-dimensional hologram float before me. I look at the detailed map of the old Kolkata, with its roads, pavements, alleys, skyscrapers, housing complexes, colonial structures, greenery, railroads, metro rails, and even models of miniature Kolkatians, all afloat in front of me. I gasp, the lower part of the visor becomes foggy by my breath. Your voice comes to me as a whisper, “One day you told me one of your deepest desires: of reliving the past, to read the last pages of the human odyssey. If you did not show me your inner monsters, how would I know you ached to be human?”

Before I can come with a good answer, I see something breaching the atmosphere, leaving a trail of light behind it.

No, No. No. I recognize the object that entered the atmosphere, the ship that was supposed to carry me home. I ask for an explanation, I scream. Over the radio, I hear you quarreling with someone. I recognize him to be your father. My vitals are probably dancing on your screen. After you return to me, I sense a disturbance in the transmission. It takes me a few seconds to realize it is your voice that is cracking. “Open the other pocket on your pouch,” you say.

I do and when I hold the detonator between my palms, I find it to be made of cheap plastic.

“It is fake. They just handed me the real one.”

Your voice sounds as if your vocal cords have snapped like twigs. I throw the hologram projector away but it still drifts around me like an obedient dog. “They knew, Imran. They always knew. I thought we could fool them but love is massacred in a city wrapped in surveillance. It is all about collective human survival where an individual can become collateral damage. My father is standing right behind me, saying it is he who pulled some strings and saved me. I am sorry. Imran, I am so…so sorry. I should have known this was bound to happen, from the day they selected you to be a part of this project. What am I other than a toy?”

Nothing. You were in charge of my suit’s assembly. How can an important piece like this be replaced without you knowing? If you did not know, I think you are the biggest of fools. If you did know, I acknowledge you as the greatest of actors. Either way, I cannot forgive you.

I don’t have that power in me, not anymore.

Yet, I say, “Hush now, my love. Do you know I saw the most beautiful sunrise today? Our planet appears like an azurite from here; the half-submerged mountain ranges are her green veins. Arun, I was alone and you came to me and made us a family. I was afraid but you taught me courage. I lived in the shadows and you brought me back under the sun. My mind only reflected the poisons of my soul until you brought me saplings of hope to plant. I was a prisoner and you set me free.

“You know what you have to do, Arun. The fate of the world depends on that button.”

I count your heavy breaths on the transmitter mic and face the sun.

Mother, if I knew, I would have carried the jar with me for you.

*******

When he is not busy constructing stellar engines in his mind, Soham Guha finds himself in his suburban home near Kolkata, the city he is so fond of. He writes in his mother tongue Bengali, and in English as well. His works have been published in kalpabiswa.com, Scroll.in, Mithila Review, Desh magazine, Kishor Varati, UnishKuri, parobashiapachali.in, Matti Braun’s Monograph and Megastructures (Mohs 5.5). ‘Our Lives on Tides’ was published in the Mohs 5.5: Megastructure anthology, which is now a part of the Peregrine Lunar Lander payload.

Dialogue with South Asian SF Writers series in The Beacon

Leave a Reply