Tarun K. Saint with Sami Ahmad Khan

Tarun K. Saint–What would be your assessment of the SF scene in the subcontinent today? As a seasoned scholar and critic of SF who also teaches a course on this genre, is this a pivotal moment for South Asian SF in your view?

Sami Ahmad Khan–The force has awakened – or maybe it did a long time ago. Even though I solely focus on contemporary India’s anglophone SF, I can safely say that this is a good time to be writing, reading, researching and teaching SF in South Asia. More and more short stories, novels, critical works, etc. seem to be coming out with each passing year. Roger Luckhurst may have referred to SF as the literature of technologically saturated societies, but the current surge of SF in/from South Asia is evident. Now, this increase in creative and critical mass can be explicated by a variety of factors: this is, in itself, worth a doctoral thesis, but this spurt can be attributed to specific conditions created by global market forces, techno-scientific weltanschaaung, demographic dividend, a desire to do something ‘new’ within/via cultural production, and an inbuilt fascination for non-mimetic modes of representation that can generate a mode of storytelling that both adopts and challenges endemic and external literary and cultural traditions.

TKS–Has translation enabled an adequate appraisal of SF emanating from regional locations, or does the language hierarchy still prevail? Can this be changed in the near-future, as we develop a corpus of SF writing from South Asia?

SAK–Untranslated literature is not unread literature, as Jessica Langer points out. SF, at least in India, has been prominent for some time now. While many readers may confuse Anglophone output with the total literary output, India has had a long tradition of SF in Bangla, Marathi, Tamil, Urdu, etc. starting in the late 19th century itself, a tradition that runs parallel to SF’s historicity in other cultures and languages, such as English or French SF. The future is now – or maybe it always was. Though I must admit that I have been a victim of a similar phantom, I did not read any Indian SF writers while growing up simply because I was unaware they existed! My ignorance led me astray. If only I knew that India’s regional languages had a rich history of SF… but a teenager me was so concerned with anglophone works that it was only much later that I chanced across Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonku etc. It made me feel horrified– there was a mighty tradition of Indian SF and I had ignored it, limited by the medium of instruction in school (English). However, things are changing fast. I think Bal Phondke’s anthology It Happened Tomorrow – which brought translations of SF stories from India’s regional languages into English–became a benchmark that needs to be emulated more. The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction has done something similar. I think the point is to write not in the preferred language of the market but one in which an author/poet is most comfortable–or not. It’s an individual choice and that must be respected.

TKS–Has SF in the regional context and in English here moved beyond the ‘supra-educational’ function of the Golden Age and after, when SF was aimed at science students for the most part?

SAK–While you have scientists like Jayant Narlikar (Marathi), DC Goswami (Assamese) and Sukanya Datta (English) writing SF, all SF is not about science communication or science popularization. SF also indicts its times and the epistemology of science and society. The SF from South Asia, particularly India’s anglophone SF (for I am not qualified to talk about South Asian SF – it is too multidimensional an entity), operates per a dual epistemic function. The first is, of course, SF written as science communication, but the second is replete with horrifying projections that refract the brokenness of our world. Together, they may also provide a template to heal it. The movement you refer to happened a long time ago. Why should scientists have all the fun?

TKS–Let us turn to key influences on your work. Which SF writers left a key imprint on your writing style as you took the decision to become a writer? Were writers in the Anglo-American tradition (Asimov, Clarke, right up to cyberpunk and beyond)more important, or werethe sub-continental epics, mythology and Indian SF writings crucial to your imagining?

SAK–First, I never decided to become a ‘writer’. Even today, my first and last reader is myself. I write because the act of writing something crazy gives me happiness at the moment I am writing it. It is a therapeutic, cathartic and intensely personal act – whether it is deployed in the market or not is a secondary concern. Moving on to key influences, well, I must point out how I view SF as a genre: I see it as a crisscrossing of warps and wefts of semantic/syntactic elements hybridized from multiple modes of storytelling (using terminology from Paul Kincaid and Rick Altman). SF is not an insulated tradition but a shape-shifting sea into which rivers of SF from different spatiotemporal locations flow. As pointed out earlier, I was deprived of Indian SF while growing up – owing perhaps to the dearth of translations into a language I understood. I grew up on Star Trek, Star Wars, Doctor Who, and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which made me fall in love with SF in the first place. However, despite swearing fealty to SF (as opposed to the SF, Fantasy and Mythology of SpecFic or the fused version of SF and Fantasy, SFF),I am slowly beginning to feel wary of essentializing or universalizing enterprises that cleave SpecFic into tidy pigeonholes. This becomes especially true of our techno-scientific times. Myth can be SF, SF can be science, and science can be realism; similarly, even the differences between the “Indian” and “Anglo-American” traditions can be problematized. For example, while Indian SF often appropriates western tropes (e.g. Koii…Mil Gaya), India’s distinct mythic frameworks make their way in SF across the world (e.g. Zelazny’s Lord of Light). While it is only logical to look at the binaries and dialectics of this SF and that SF, the inherent universality and polyphony of a genre/mode such as SF–a universal genre/mode that belongs to all of humankind–can only be understood in/as a holistic, gestalten whole. If SF belongs to multiple dimensions, its readers and writers must also strive for a synoptic, trans-dimensional view of the semantic elements that comprise SF.

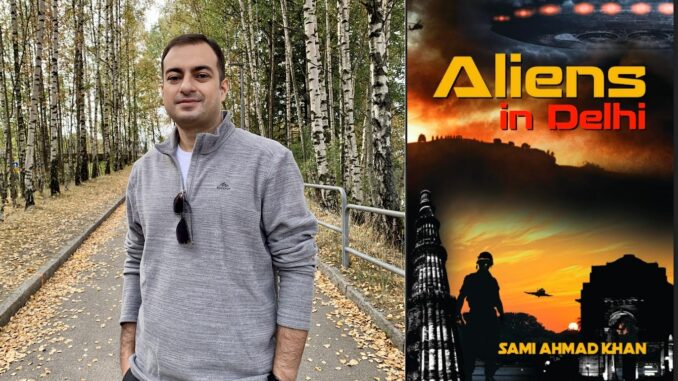

TKS–Your SF novel Aliens in Delhi appeared in 2017. The novel envisages a distinctive variant on the alien invasion theme, with the reptiloid invaders using communications technology to make inroads. Share with us the genesis of this storyline, especially with respect to the challenge of reconciling ‘serious’ and ‘pulp’ elements.

SAK–In Aliens in Delhi, I wanted to fuse the political thriller with classic SF. The idea came to me one day as I was riding on Delhi’s crowded Ring Road and saw the Pitampura TV tower rise up in front of me. From a particular angle, it looked like a space gun – and this set the ball rolling. Through this particular novel, I wanted to experiment with how characters change when placed within a different genre. My goal was to destabilize the metaphorical underpinnings of the quintessential alien figure by placing it within South Asian geopolitics. This is why when I wrote about people in New Delhi turn into reptilian hybrids. As for the differences between serious and pulp elements, I chose what organically flowed into the story. My first love is pulp, the subtle insertion of serious themes into ostensibly mindless pulp is what gives me the kicks – and that’s why I write. Though I still don’t agree with any division between serious and pulp. Lot of serious literature was either pulp in its times, or would be seen as pulp in the far future. Pulp lies in the eyes of the beholder.

TKS–The forthcoming story ‘Biryani Bagh’ (in the Gollancz Book of South Asian SF, vol.2) takes forward the theme of ‘alien-nation’ seen in your novel. Comment on the notions of alterity and difference underlying this story, with its resonant allusions to contemporary protests.

SAK–While politics, protest and pulp almost always flow together in my head, “Biryani Bagh” is overtly more political than other works – this time the metaphors that operate within the text are easier to identify owing to the topicality of the narrative. I decided to have fun in this story by literalizing the metaphor and metaphorizing the literal. I wouldn’t go into the specifics of allusions etc. here – that may spoil the fun of reading😊

TKS— Let us know a bit about work in progress, including forthcoming books and stories in the SF vein.

SAK–I am working on a critical lead I have. The past couple of years have had me attempting to explicate the behaviour of India’s anglophone English SF. My latest book (Star Warriors of the Modern Raj) comes up with an ‘IN situ model’ that advances three nodes vis-à-vis the space, time and being of India’s SF: the ‘transMIT thesis’ evidences how Indian SF transmits (emergent) technologies, (sedimented) mythologies and (mutating) ideologies across/through its narratives; the ‘antekaal thesis’ interrogates the ruptured temporalities of Indian SF; and the ‘neoMONSTERS thesis’ approaches marginalisation-monsterization as contingent on specific material realities. Presently, I have started to focus on the neoMONSTERS – mutating ontological narratives in space-time echoing realistic situations–thesis to comprehend to how monstrosity and alterity are constructed, deployed and interrogated in India’s SF, and how they interface with the world(s) in which they are produced and consumed, especially when religious and political ideologies collide and collude.

A question from Alok Bhalla–Is writing serious SFF basing oneself in societies (or communities) which are fundamentally religious and superstitious more of a challenge? One can, of course, write SF as a dark satire about such communities in the manner of Swift’s Voyage to Laputa or, perhaps look back with nostalgia from a late 3045 BC about a distant past when Hanuman could fly and carry back a mountain for a magical herb (Incidentally, the Black Panther movies do something similar by imagining pre-colonial African with Shamans). Even a brilliant novel like The Overstory, by Richard Powers, has difficulty with the Indian (Hindu, of course!) commuter geek in some future time who whines about Indian gods even as he creates complex modules. What was the vision of Indian social structure underlying your novel, Aliens in Delhi?

SAK–Now, I don’t aspire to write “serious” SF at all, but I love how the aliens, robots, clones, zombies, time-travel, CBRN warfare, etc. of SF make us re-envision our collective futures. I categorically reject the labels of serious or pulp – for even reductive, pot-boiling pulp can sometimes foreground something really important to the society which serious SF – with its emphasis on form and aesthetics – can totally ignore (and vice-versa). SF has its own polyphony: for example, Wakanda meets its antithesis in Aryavrata. Alternative and indigenous futurisms can be equally revolutionary and reactionary, left or right, anti-racist or pro-racist. As pointed out earlier, I write for myself and don’t think of narratives that come to me as pulp or serious, but as stories – and focus on a plot/narrative that makes me happy. With Aliens in Delhi, the focus was not on the future but the present – and how a generic hybridization between two distinct modes of storytelling (SF and political thriller) could create a narrative with semantic elements of both, all the while having a new syntax. SF, South Asian geopolitics and thrillers provided a canvas where all three could bring their ontological nuances into an ostensibly “pulp” narrative.

AB— One of the crucial problems that has troubled SF writers from the time of Frankenstein onwards is that of imagining human love (and sexuality) in future time. Human love is either monstrous or impossible. Think of Karl Capek’s RUR or Kazuo Ishiguru’s Never Let Me Go, where love as a sentiment important for the survival of our future becomes unimaginable. In Chris Marker’s great film, La Jettee, the man trapped in a dark authoritarian future travels back in time only to realise heartrendingly that love is now only a fading memory. In Tarkovsky’s haunting version of Solaris, the protagonist understands that love in future time can only be the love for simulacra. To what extent did speculation encompass the realm of love/eroticism for you personally while writing SF narratives?

SAK— Hain aur bhi gham zamane main mohabbat ke siva. I have, till now, consciously veered away from writing of/on love–for that requires a level of comprehending human psychology that is beyond me at the moment. I prefer to write of another kind of love, a love more readily accessible, though equally, if not more, intoxicating – the love of triumph, the love of destruction, the love of domination, and the love of absolute control. As human history has taught us, what can be more romantic as an ideal than a genocide (of the other)?

TKS/AB— In the subcontinent, ghost stories about the superstitious past have had a conservative dimension, perhaps due to fear of change. Has contemporary speculative fiction, including your work, become a vehicle for making more sharply critical statements about present day dilemmas, whether in the domain of religion, ecology, gender relations or politics eluding the traps of informal and formal censorship in the process?

SAK— SF is a double-edged sword. It can propel one towards the dark side with as much panache as towards the light. However, most of India’s contemporary anglophone SF has engaged in a sustained critique of mindless violence, fanaticism, extremism, etc., in short, the maladies which plague our current world. To cite a few examples: Mainak Dhar’s Zombiestan critiques Islamist terror; Rimi Chatterjee’s Signal Red denounces Hindutva fanaticism; Anil Menon’s The Beast with Nine Billion Feet advances a dialectics of capitalist market forces and the global south; Shovon Chowdhury’s The Competent Authority satirizes multiple aspects of the world around us; and concerns of class and caste intertwine in Priya Sarukkai Chabria’s Generation 14, Manjula Padmanabhan’s“2099”, Payal Dhar’s “The Other Side”, and Vandana Singh’s “Almaru” etc. Using metaphorical projections and critical interventions, SF becomes a battleground where the ‘Other’ is constructed and controlled across domains of society, religion, politics, ecology, etc. This is, clearly, a subtle, yet somehow more direct, way of critiquing external reality and the times in which literature and society intertwine.

(The neoMONSTERS project run by Sami Ahmad Khan has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101023313)

**

Earth Report 1: On board Qa’haQ Shuttle D’bHin, Punjabi Bagh, New Delhi, India

Sami Ahmad Khan

Today; zero hour

The skies groaned softly.

A gentle unseen ripple ran through the polluted air above Delhi’s Ring Road as the Qa’haQ planetary landing vehicle uncloaked for a split second and shimmered into existence. Some pieces of junk – which human cars belched into the atmosphere with alarming nonchalance – had collided with the invisibility shields. The organic circuitry aboard the ship chattered to compensate for this tactile assault.

Ensnared in a traffic gridlock, a bewildered Madhav Khanna stared at the apparition through the tinted glass of his teakbrown Audi Q7. Before he could finish gawking and raise an alarm, the spaceship disappeared, leaving Khanna cursing his eyesight.

Oblivious to the blaring car horns, the resident AI aboard the dark, dank bridge of the alien craft was playing a soothing meditation song. The Qa’haQ mother ship in orbit was but an exploratory science vessel with a complement of fifteen, and it had assigned two officers to take a cloaked shuttle down to Earth’s surface for a reconnaissance run.

Commander S’aulk, the leader of this small surface party, was in his chair, humming a melody under his breath. Sub-commander Dac’ish, the pilot and executive officer of the shuttle– attentive, efficient, and observant –sat in front of the faintly glowing Operations Console as she navigated the narrow, SUV-infested by-lanes of Punjabi Bagh.

An instrument beeped thrice. Dac’ish slid a slender reptilian claw across an octagonal panel. A screen sprang to life. Her eyes focused on a pulsating blip and blinked, processing the new information with the help of neural implants. She assimilated the data and tensed ever so slightly.

‘Commander S’aulk,’ Sub-commander Dac’ish reported, a note of concern creeping into her voice, ‘we have a development.’

‘Report,’ S’aulk shrilled absentmindedly.

‘We’ve received a priority message from the Qa’haQam – it is being relayed to us via the mother ship.’

The oval bridge suddenly fell quiet as the song automatically muted itself. The soothing forest noises of the Qa’haQ home world faded into nothingness, the beeping of instruments taking their place.

‘What is it?’ Commander S’aulk dropped the precious Orcheum flower he was sucking, his yellow eyes widening to perfect circles.

Dac’ish’s short tail quivered for exactly two seconds to denote certainty. Her claws became a blur. After a few moments, she slowly turned around and hissed, fighting to keep her voice even. ‘It is confirmed, Commander. We have been ordered to activate the Genetic Transmutor.’

‘What? Are you sure?’

Dac’ish waved her claws across a few lighted panels. ‘The order has been authenticated by the Qa’haQ Central Command.’

S’aulk muttered to himself, ‘But we were only supposed to observe and report back.’

He was so lost in thought that he didn’t realize that Dac’ish was impatiently drumming her claws on the console. Her eyes were a shade of brown now, and her skin had changed colour to match that of the bridge – the basic Qa’haQ defence mechanisms, even if involuntary, had kicked in. Her senses were heightened in anticipation of danger, and a piece of hard green cartilage slid over her neck from inside her exoskeleton, protecting the soft reddish flesh of her throat from immediate physical attack.

Dac’ish had already taken up battle posture by inserting a claw into the computing input device to provide the ship with immediate instructions. After all, such fragile situations demanded split-second decisions or new commanders who could issue them.

She cut in coldly, ‘We have our orders, sir. Should I contact the CentCom for a direct verbal command?’

At that precise moment, a monstrously filthy DTC bus swung so close – with a passenger leaning out to retch– that the navigational computer of the D’bHin had to engage in emergency course correction. Inertial dampeners groaned to protect the occupants of the ship from unwanted jolts.

‘No, no need for that,’ S’aulk hastily countered, mindful of the implications of doubting orders from the home world and unmindful of the crazy traffic outside. ‘Do it!’

Sub-commander Dac’ish nodded and put the information into the genetic warhead. ‘Powering up and activating Genetic Transmutor. Priming the radiation amplifying devices. Rewriting their software now.’

‘Good.’

‘Target, sir?’

S’aulk was not sure where exactly he wanted the genetic incursion to begin. He spun a holographic globe and randomly pointed a claw at one location. ‘Here.’

As the globe stopped spinning, the first officer nodded and acknowledged the order.

Dac’ish withdrew her claw from the input machine and looked squarely at S’aulk, who just stared back at her.

‘What else do you want me to do, sir?’

The bridge had suddenly warmed up. S’aulk grinned in response, knowing that Earth Sector JVHN-20, or New Delhi, the precise location where they had initiated the genetic assault, was going to get much, much hotter.

*******

Sami Ahmad Khan is a writer, academic and documentary producer who also researches and teaches Indian Science Fiction. The recipient of a Fulbright grant to the University of Iowa, USA, Sami holds a PhD in Science Fiction from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He has taught at IIT Delhi, JNU, JGU and GGSIP University. His future-war debut Red Jihad won two awards and his second novel–Aliens in Delhi– garnered rave reviews. Sami’s creative writings and critical essays have appeared in leading journals, anthologies and magazines, his overview of Indian SF has been translated into Czech, and his fiction has been the subject of formal academic research. His latest book is Star Warriors of the Modern Raj: Materiality, Mythology and Technology of Indian Science Fiction (University of Wales Press, 2021). He is presently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the University of Oslo, Norway.

Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers series in The Beacon

Leave a Reply