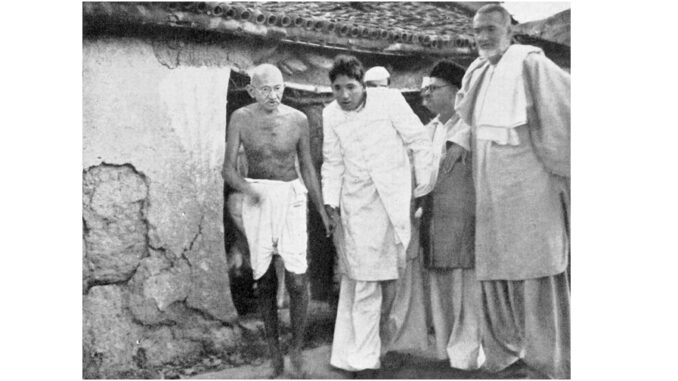

In the riot affected area of Bela, Bihar, March 28, 1947.

Sudhir Chandra

I

t should be impossible to think of 2nd October without recollecting what Gandhi said on that day in 1947. His words should be etched in our remembrance of the man. Instead, in a master stroke of instinctive self-deception, we have buried those words deep in collective oblivion. Those unremembered words are:

Indeed, today is my birthday…. This is for me a day of mourning. I am still lying around alive. I am surprised at this, even ashamed that I am the same person who once had crores of people hanging on to every word of his. But today no one heeds me at all. If I say, do this, people say, no, we will not…. Where in this situation is there any place for me in Hindustan, and what will I do by remaining alive in it? Today the desire to live up to 125 years has left me, even 100 years or 90 years. I have entered my 79th year today, but even that hurts.

(Translated from Gandhi’s Hindi original by Chitra Padmanabhan.)

I read these words as a mature man of 60. I had by then read and seen enough to be rid of our usual illusions about human nature. In the course of a prolonged engagement with the emergence and spread of nationalism in our country, I had seen the ugliness of this phenomenon which remains hidden behind its bewitching facade. Yet, I was shaken by those searing words. They still haunt me.

That was not a solitary outpouring of agony. Driven to see what Gandhi was feeling and saying in the months immediately preceding and following his ‘confession,’ I realised that this constituted the chief strain of what he described as his aranyarodan, cry in the wilderness. By early June, a month and a half before independence, he had stopped talking of living for 125 years. From then on, confessing that he was saying the same thing everyday, he began detailing his saga of sorrows, ‘meri dukh ki katha.’

As the paralysis of that first shock began to subside, a chain of thought and a new way of seeing set in. What could possibly have led Gandhi, in the hour of independence, to be so disillusioned as to lose his famous resolve to live and serve humankind for 125 years? Further, whatever may have led to it, what does it mean for a Gandhi, the incorrigible optimist and indomitable fighter, to not want to live? His moral scheme did not countenance the idea of suicide. But, given his faith in prayer, he was attempting precisely that. In any case, to lose the will to live and crave, seriously, for death is not vastly different, and distant, from actual physical death.

This is an unsettling thought. It upsets our comforting view of Gandhi’s assassination as one definitive event, and of Nathuram Godse as his sole assassin. It pluralises the assassination and the assassin. And leaves none of us unimplicated.

Gandhi was convinced – and would occasionally say so – that his lament was not about his own sorrows alone. His sorrows were the whole country’s sorrows, ‘sare Hindustan ke dukh.’ He was not wrong.

The sorrows that weighed upon him were: the country’s partition and the resultant violence; virtual disavowal of non-violence by Gandhi’s closest associates who were now the country’s rulers; neglect and exploitation of the poor; summary rejection of the model of free India that he had envisaged in his seed-text, the Hind Swaraj; and corruption within the government.

He shuddered to think of where all this would end.

Hindustan did not think so. It cast Gandhi aside and rendered him helpless by refusing to heed him. He saw everything, foresaw the dark ahead, and bemoaned: ‘Whatever is happening in this country that could make me happy?’

There was, however, one man, Vincent Sheean, who knew what was happening. Following Louis Fischer, William Shirer, Margaret Bourke-White, and Edgar Snow, Sheean was the last among the distinguished quintet of American journalists who felt powerfully drawn to Gandhi. For long, despite being goaded by his friend Shirer, Sheean had been content with knowing just enough about Gandhi to get a sense of his greatness. On his own admission, his frivolous and self-indulgent life had not allowed him to engage seriously with Gandhi.

Then, suddenly, sitting far away in his farmhouse in Vermont, Sheean began, ‘for some reason or for some unreason, to feel perturbed and anxious about Gandhi.’ The anxiety soon grew into the conviction that Gandhi was going to die. He would be martyred by his own people. This, Sheean saw, was inevitable.

The persistent premonition of Gandhi’s martyrdom by his own people acquired such clarity and precision that nine days before the actual deed Sheean noted in his diary that the killer would be a Hindu, not a Muslim. ‘This,’ he wrote, ‘is in the logic of every sacred drama in the entire history of religion.’

The engagement with Gandhi that he had long deferred acquired urgency. Sheean knew that Gandhi was the only one from whom he could obtain ‘some clue to the meaning of our struggle,’ of the very purpose and significance of human life. He rushed to New York to meet William Shirer and requested him to use his influence and facilitate a meeting with Gandhi. Sheean reached Delhi just in time to have two conversations, each one-hour long, with Gandhi on 27 and 28 January. Since he was going to the Panjab with Prime Minister Nehru on the 29th, Gandhi asked him to come on 30 January and try his luck in case a third interview could be fitted in after the prayer meeting. Back the following evening to try his luck, Sheean saw his terrible premonition materialise.

Dazed and in unspeakable misery, Sheean was consumed by one thought: ‘How can such things be?’ Two years later, in his Lead, Kindly Light: Gandhi & the Way to Peace, he came out with a long meditation on the question.

Sheean was unique in his prescience about the inexorability of Gandhi’s imminent assassination. It is not surprising that there were not many like him. What is surprising is that, even after the deed was done, not many understood what had happened. Not even from among those who had heard, day after day, Gandhi’s unceasing recital of his – and their – woes. They seemed too overwhelmed to think of anything other than grief. There were, of course, exceptions. A future great of Indian fiction, Krishna Sobti, then only 22, had the self-reflexivity to describe the assassination as pitra-hatya, patricide. Even William Shirer needed the actualisation of his friend’s premonition to grasp the larger significance of the assassination. Only in retrospect did he realise that Gandhi’s life had, indeed, marked him out, inevitably, for the end that Socrates and Christ had met before him.

These great martyrs’ ends never end. Talking only of Gandhi, he was killed more than once before Godse took charge; he is being killed posthumously as well. Let us return to his aranyarodan of 2 October 1947. He followed up his general lament about living on in spite of his redundancy with a pointed reference to the Hindus’ insane hostility towards the Muslims and their behaving like they owned the country. But even that aranyarodan, shot through with despair as it was, carried a semblance of faith and hope as it ended with offering the people a chance:

‘If you really wish to celebrate my birthday it is incumbent on you to ensure that we will not let people go mad and will cast off whatever anger there may be in our hearts.’

People curbed neither their anger nor their madness and went merrily on to celebrate his birthday, unaware that that was killing the helpless old man.

The tradition set in the first year of independence has since gathered momentum. Gandhi’s birthday – now also the International Day of Non-Violence to boot – is observed every year without fail. In the meanwhile, corruption, violence, neglect and exploitation of the poor, religious fanaticism – the sorrows he harped on during the few days he lived among his free compatriots – have grown exponentially. One of those sorrows – religious fanaticism – was the immediate cause of his assassination. Godse, the physical assassin, was a Hindu fanatic. For quite some time after he had done the deed, it seemed that the ideology on the lunatic fringe of which he then stood, had been swept away by the shock waves the assassination had produced. To that very ideology have Gandhi’s own people now entrusted the running of his – their country.

Another incriminating fact, like Gandhi’s cry on 2 October 1947, that we have kept out of our everyday remembrance of him is the duration of his life in free India. Counting out his struggle in South Africa, Gandhi fought the alien rulers for thirty years after returning home. No harm came his way. The worst they did was to incarcerate him from time to time. But never during his 2089 days in their prisons did they treat him except with great courtesy. They made his prison life comfortable, permitting him, normally, facilities like the company of his private secretary, access to books and newspapers, and correspondence with the outside world. There were incarcerations when much of his entourage was around him. His wife breathed her last in his arms in jail, so did his beloved long-serving private secretary. In independent India, among his own people, Gandhi survived less than half a year.

Unlike what Gandhi said on 2 October 1947, the number of days he lived in independent India is not something confined within books. It is a simple count between 15 August 1947 and 30 January 1948. That count lays bare an ugly reality we would rather not face.

Just how effortlessly we have managed to protect ourselves was brought home to me, rather unwittingly, by an American political scientist, David Lumis. We were together on a long train journey. Just as I was going to sleep, David came and asked me straightaway: ‘Sudhir, what do you think was the immediate reaction of Gandhi’s close associates to his assassination?’ I was completely taken aback by the question. Nothing half as inconvenient had ever crossed my mind. My first instinct was to say that I had not thought about the matter and would rather come back with my answer. But before I could say so, a rapid reflection ran through my mind and I found myself answering: ‘I think their first response was one of relief, and before they could feel guilty about that, they were overtaken by grief.’

Years later I read three extraordinary lines by Jayanta Mahapatra about our fraught relationship with Gandhi. Matching Gandhi’s simplicity and brevity, Mahapatra says:

We love him,

We hate him,

We do not know it.

It was around the same time that I stumbled upon Krishna Sobti’s pitra-hatya. Both Sobti (born 1925) and Mahapatra (b. 1928) had seen Gandhi and, as gifted impressionable individuals, experienced first-hand the time in which were born the sorrows Gandhi died talking about.

Why, even at this distance in time, can we not see what these exceptional contemporaries saw, and Vincent Shirer foresaw? Besides, a great deal more is at stake today. We never needed Gandhi like we do now. But he can be of no use to us if we cannot be a little more honest and unafraid. Honest and unafraid enough to face up to our role in killing him. Godse was an honest man. He knew what he was doing and died for it.

We know neither that we have been killing Gandhi nor that, in the process, we are killing ourselves as well.

******

Sudhir Chandra is a historian. He has made a notable contribution to our understanding of the kind of society and consciousness that we have inherited as part of our colonial legacy. His publications include Dependence and Disillusionment: Emergence of National Consciousness in Later 19th Century India, The Oppressive Present: Literature and Social Consciousness in Colonial India, Enslaved Daughters: Colonialism, Law and Women’s Rights, Continuing Dilemmas: Understanding Social Consciousness, and Gandhi: An Impossible Possibility, Violence and Non-Violence across Time: History, Religion and Culture (edited).

Sudhir Chandra in The Beacon https://www.thebeacon.in/2017/09/30/in-bloodbath-moral-vision-reasserted-between-the-lines/

I am lying on my hospital bed, and have just finished reading Sudhir Chandra’s essay on the Gandhi’s first birthday in Free India. A deep sadness runs through me, not in that we have cunningly forgotten to turn inwards to lay our finger on that pulse between the shock and grief of Gandhi’s killing, but because we are going through all that he – and perhaps a handful of others – had foreseen, again and again. Madness, indeed. But is that madness also a convenient mask, albeit of hatred and empty fury, but a mask that is quite like what happened around 1947 and 1948 – that prevents us all from saying, forgive me father, for i do know what i am doing. All i can say after reading this is that i have enough stoicism to go in for my procedure early tomorrow morning to find out where i am bleeding internally. Because we have bleeding as a nation all these years and still are – but at least this doctor and his team will locate this bleed and stem it