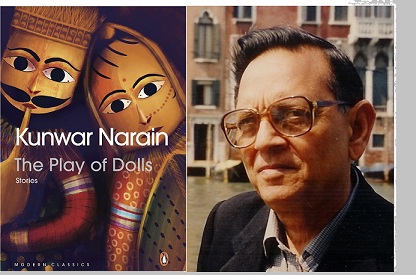

The Play of Dolls: Stories. Kunwar Narain

Translated by John Vater & Apurva Narain

Penguin Modern Classics, India, 2020

www.amazon.in/Play-Dolls-Stories-Kunwar-Narain/dp/0143446959

Prelude

On the occasion of his birth anniversary,19 September, The Beacon pays tribute to Kunwar Narain (1927-2017), re-issuing a collection of his works, first published in this journal 30 April 2021.

Also included are links to some of the events that were organized in his remembrance 17-19 September 2021.

**

Kunwar Narain

The Court of Public Opinion *

SADIQ Miyan managed to keep his motives in check at first, but then they went awry. A completely new bicycle, stood completely unclaimed—without even a lock to guard it! He glanced around once, then ran his hand over the bike’s glittering handle, as if caressing the mane of a magnificent Arabian horse. He couldn’t hold back any longer, and jumped on the bike. No one objected, nor noticed; and, well, what could the poor bike say either? He pushed down on the pedal lightly. The youthful cycle was ready to take off with him right away. The people nearby came and went by as usual, just as before.

Sadiq Miyan spurred the bicycle on, and it began to fly like the wind. It was his now.

But, alas, what an awful stroke of bad luck! An endless herd of buffaloes came along, straying right into the middle of the road. Sadiq Miyan lost control and collided with one of the stoutest in the bunch—head-on. What could he do, the poor guy? He hit the ground—his own injury less, the cycle’s, more. Bent and broken, the wheel went from being hoop-shaped to heap-like. The handle, twisted backwards, gazed at the seat, and the mudguard took on a look as if it were not a part of the bike but of the buffalo. The buffalo stood in stunned silence; Sadiq Miyan glanced nervously at the crippled bike. What could he do? He’d really landed himself in a strange sort of trouble. It crossed his mind to abandon the bike and make a run for it. After all, it was only the bike that was broken—nothing wrong with his legs!

But in the meantime, a crowd began to gather all around him, as was only natural. Running just then would have meant getting himself in more trouble. Two, four, six . . . dozens of women, men and children began surrounding him. In the middle lay the mangled bike; with the buffalo, chewing cud, on one side, and Sadiq Miyan, head reeling, on the other.

At first, the people pitied the bike that was now a mess, then their hearts were kindled with compassion for Sadiq Miyan, and finally, they got angry at the buffalo. Because there was clear evidence before them of what happens when one locks horns with a buffalo, they decided to tackle the herdboy instead. It was because of him that the hazard of something like a buffalo had sprung up in the middle of the road, and someone upright like a Sadiq Miyan had become the victim of that hazard.

By consensus, it was decided that they should fix the herdboy properly, right then and there. But Sadiq Miyan objected: in his view, it was more important to fix the bicycle first—and the herdboy should be made to do that. Everyone agreed.

The crowd lifted the bike tenderly and delivered it to a nearby cycle hospital with great care, where its wounds were treated for a cost of ten rupees. But when the herdboy was told to cough up the money, he expressed his inability to do so, and asked how on earth was he supposed to come up with ten rupees when he hadn’t even ten paise to his name then?

Confronted by this new problem, an extraordinary debate took place among the ordinary folk assembled there; so many arguments all at once that it was practically impossible to make out any argument clearly. Nevertheless, one solution somehow seemed to survive intact: whatever the herdboy was wearing should be sold to cover the penalty cost of the repairs.

This too was easier said than done, because the herdboy had nothing but a dhoti around his waist and a lathi in his hand. Even if both these items were taken, it wouldn’t be enough.

Anyhow, after the cycle had recovered, it was agreed that Sadiq Miyan and the cycle should be considered free from the whole dust-up. This was deemed incontestable not only in the eyes of the public, but also in the eyes of the luckless bicycle mechanic, who now, having taken the entire burden of Sadiq Miyan’s ten-rupee misadventure on his own head, was an eager prosecutor of the blameworthy herdboy. As for the public, it was surely commendable that not a single person there was willing to step back until final justice had been delivered, no matter what.

Some wise guy then repeated the suggestion that, if it satisfied the cycle mechanic, the herdboy could also be handily fixed, with a flogging worth ten rupees! But nobody paid much mind to this idiocy, though the herdboy was entirely willing to go along. Everyone’s attention was stuck on the intricate problem at hand: how could they wring ten rupees from the herdboy in his present condition?

One gentleman, who had perhaps trained as a lawyer, or was capable of being a lawyer, came up with a novel proposal: by selling that same buffalo which had given rise to all this mess, the cost of the fine could be recovered. The idea wasn’t unreasonable, and his submission was accepted.

The buffalo again became the centre of attention. For five minutes, the people waited. But where would they find a ready buyer for a thing as big as a buffalo? A buffalo isn’t some wad of paan, a bidi or a cigarette that can be purchased along the road, tucked in one’s pocket, and hung along with the pocket on a peg on some wall back home. It was a matter of responsibility, which could go as far as spelling fortune or disaster for one’s offspring. Second, who had the cash on hand worth a buffalo at this time? As a result, this attempt at justice proved unsuccessful as well.

Around now, everyone was sorely feeling the need for some kind of mastermind in the crowd. A few sights fell on one particular gentleman, and remained on him. He certainly looked like a wiseacre—though some others pegged him as a daydreaming wiseass. They held a vote; and it was decided that he was indeed a wiseacre, not a wiseass, though he himself kept claiming to be nothing less than a prophet. Well, he could think of himself as whatever he wanted, but he couldn’t get past what the public thought of him; and he was forced to become what they made him become.

It was his opinion that ten rupees’ worth of milk be squeezed out of the herdboy’s buffaloes, and sold on the spot. Milk was something that everybody could immediately buy a little of, and use then and there. The idea was undoubtedly so fantastic that the crowd wholly and willingly welcomed the decision with a hearty round of applause.

The buffalo was milked. Several seasoned people completed the task with much skill and gusto. Then, someone bought a quarter kilo of the milk, another a quarter and a half, someone half a kilo . . . and drank it right there. To stumble upon a rarity like fresh milk undiluted by water, at such a bargain price—well, who could object to buying it? In fact, the crowd only regretted it a bit that the penalty price wasn’t higher than ten rupees!

The payment was thus settled, but then, amidst all this, an unexpected event occurred that compelled them to rethink their justice once again.

During the time the buffalo was being milked, a pitiable state had befallen the herdboy. Some felt a little injustice had been done to him in the heat of meting out justice. His guilt was not so great as to merit such a grave punishment. After all, it was the buffalo’s fault—the herdboy’s only fault was that the buffalo was his! An elder in the crowd took inappropriate advantage of the situation and imposed an unsolicited folk proverb on them: ‘When you can’t defeat the dhobi, then box his poor donkey’s ears.’ Despite the fact that this use of the proverb was opposite to the situation at hand, all grasped his point straightaway. This is perhaps the greatest virtue of proverbs: use them correctly or turn them upside down, they mean exactly what you want them to mean.

The full effect of the herdboy’s state—or sad state— was felt most acutely by a woman, who at that moment also happened to be the crowd’s most beautiful and heart- warming constituent. From the start, she had felt pity for the herdboy, but what could she say before justice? She had managed to control herself, somehow. But when the tide of fellow feeling also began to shift towards the herdboy, the dam holding back her self-restraint broke down. Who knows which of the herdboy’s pained postures it was that plucked her infinitely gentle heartstrings, and her soft sighs began to play a poignant portamento. The people’s hearts, which were not made of stone, melted, partially due to her tears, but mostly due to her beauty. An ocean of compassion swelled all around. The people regretted their actions, and rushed to redress the injustice they had committed against the herdboy.

Each, according to their feeling, began to shower him with four-anna coins, eight-anna coins, even a rupee, with such fervour as if they would atone for a lifetime of sins right then. Their sense of virtue, rather than their sense of power, was in full swing now, and it was clear that the herdboy would benefit to the fullest from it. In front of this religious outpour, even if the icon of the herdboy were there in place of the boy himself, it wouldn’t have made the slightest difference. Overwhelmed at receiving over twenty rupees instead of ten, the herdboy first lauded the buffalo silently in his heart, then thanked the Almighty, and finally looked at the public as he beamed with joy. At that moment, everyone’s eyes, except the buffalo’s, sparkled with tears of generosity. After showering so much adoration, their hearts felt light as flowers. Sadiq Miyan, happy; the cycle mechanic, happy; the herdboy, happier than both; and the people, happiest of all. Now that’s what you call true justice!

~

That same day, around the same time when all this was taking place, not far away, another somewhat commonplace incident occurred. I think, while I’m at it, I should say something about this as well.

A man had just stepped out of a shop after buying a few things, only to find his brand new cycle missing. At first, his palate dried up, sweat beaded his brow. A new cycle— even its full cost hadn’t been paid off!

There was a paan shop nearby.

‘My bike was just here! Do you know where it has gone?’ he asked the paan seller.

‘Did you not lock it up?’ The paan seller asked a valid question.

‘No.’

‘Then it must have gone for a stroll, to take the air!’ said the paanwalla mockingly, looking at the man as if he had gone off his head.

‘Then what are you complaining about, sir? You had yourself made all the arrangements for the cycle to be lifted,’ said a second gentleman.

‘It would’ve been a surprise if the cycle wasn’t lifted,’ opined another.

‘The height of stupidity . . .’ a third weighed in.

‘A cycle with no lock, and you complain to others!’ erupted a fourth, unable to hold back.

‘Go home, sir. Go home now, and pay the price for your stupidity,’ ruled a fifth, and closed the case.

(* First published in the journal Ploughshares, in an earlier version)

* * *

Remembering Kunwar Narain. 17-19 September 2021,

Engulfed in the Formless … (34min.) a film by Gautam Chatterjee

Excerpts from Kunwar Narain’s ‘Kumārajīva’ | कुँवर नारायण के ‘कुमारजीव‘ से चयनित अंश

Kunwar Narain’s Poetry and Ceramic Art Works – Three Artists and Short Films

Jīvan Rāga | जीवन राग — Excerpts from a concert by Shubha Mudgal

Kunwar Narain’s Poetry: The Translator’s Voice

Five Films on the Poems of Kunwar Narain

![]()

Witnesses of Remembrance: Selected Newer Poems.

Kunwar Narain. Translated by Apurva Narain

Eka, Westland Publications, India, 2021

www.amazon.in/Witnesses-Remembrance-Selected-Newer-Poems/dp/9390679028

In the Queue of People

These arrows, quivers and scimitars,

these clarions, these eulogies,

beyond their ambitions

blessed is the serene journey

of the bare-headed and bare-footed.

I accept that I’m no paladin,

that I’m ordinary;

what will I do amassing

a wreckage of weapons

and wounds on my body?

Humble, I stand with all

in the queue of people tired

of manoeuvres and counter-manoeuvres.

They who had arrived

with their camps, covenants and regalia

even before the battle

returned crestfallen, seeing

no verve in me for war or warrior;

Seeing my signature

on pacific overtures of amity, meant

to quash animosity with love,

they became wary

of my stance to remain free.

**

The Killing of the Heron *

We are the aching wound

of a nation passing

through fragile times,

the defence for life

standing like a convict

in the courtroom of death,

We are the testament

of innocence breathing its last

in a world brimming with venom,

the hapless, star-crossed people

whose blood now flows

not in veins but in streets,

A wounded tree, love

drying out twig by twig

under the merciless winds,

we are the bad times

of a man with an axe

hatcheting his own roots…

Returning from rama rama

back to mara mara, are we

a home for termites to dwell in?

Perhaps, we are the most tender

note in the sloka that had bewailed

the killing of the heron then.

*Legend has it that Valmiki was a robber first; sages once told him that true treasure could only be found in (Lord) Rama, and brought him to realisation. But he couldn’t utter this word, so they had him chant it in reverse as Marā…Marā (killed), something he could say, which soon became Rāma…Rāma. During his long penance, as he sat chanting, a termite-hill (vālmīki in Sanskrit) built around him. Later, after his transformation, he was once on a riverbank with a pair of herons in peaceful bliss nearby. Suddenly, a hunter shot one down. The painful wails of the other so shook up Valmiki that he uttered a curse, amazingly in anuṣṭup verse, a rhythm-type with eight syllables to a pāda (foot). He became a harbinger-poet, and this the first ‘śloka’ of the Rāmāyaṇa, the first Sanskrit epic. The heron is also said to be a symbol in other cultures: of luck and patience in Native American tribes, purity in Japan, a path to heaven in China, a creator of light in Egypt, and a messenger of God in Greek myth. Its killing here is conflated with our abject times, and redemption alluded to in the epic it triggered.

**

Arrival of the Barbarians *

(After Cavafy’s Waiting for the Barbarians)

It is no use fretting about anything

Now. They have arrived. Once again

They have trounced and conquered us.

Their officers, constables and brigadiers

Counsellors, bailiffs, henchmen and jesters

Pimps, sycophants, jobbers and soothsayers

Their lackeys, marshals and their courtiers—

They are there, shadowing us

Everywhere. All of them

Have come back, again

They have taken over all the common

And special places in the city all over.

Their mobs are now raring

For a free hand to maraud.

* First published in the journal Asia Literary Review

*******

The Beacon thanks Apurva Narain for arranging this selection and the respective publishers for permission to publish the selections.

Kunwar Narain (1927–2017), is considered one of India’s foremost poets, thinkers and literary figures of modern times. His work spans diverse genres, and includes three epic poems, poetry across eight collections, translations of poets like Cavafy, Mallarmé, Borges, Herbert and Rózewicz, and books of stories, criticism, essays, conversations, and writings on world cinema and the arts. His oeuvre of seven decades, since his first book in 1956, has evolved continuously and embodies, above all, a unique interplay of the simple and the complex. His honours include the Sahitya Akademi award and Senior Fellowship; Kabir Samman; Kumaran Asan award; medal of Warsaw University; Italy’s Premio Feronia for distinguished world author; Padma Bhushan; and the Jnanpith. A reclusive writer, some of his works remain unpublished. Apurva Narain is Kunwar Narain’s son and translator. His books include a translated poetry collection No Other World, a co-translated short story collection The Play of Dolls, and the just-published collection of poetry translations Witnesses of Remembrance. His work has appeared in several literary journals, such as Asymptote, Modern Poetry in Translation, Indian Literature, Asia Literary Review, Scroll, Poetry International, Two Lines, Columbia Journal, etc. Educated in India and at the University of Cambridge, he writes in English and has been an avid traveller. He has professional interests in the fields of international development, ethics and ecology. John Vater holds an MFA in literary translation from the University of Iowa. The Play of Dolls is his first book in translation, co-translated with Apurva Narain. In 2018, he was selected as an emerging translator from the US to attend the Banff International Literary Translation Centre Residency in Canada. His translations have appeared in Ploughshares, Asia Literary Review, Words Without Borders, and Exchanges. He works as a research associate at the Institute of South Asian Studies in Singapore.

Leave a Reply