Mridula Garg

E

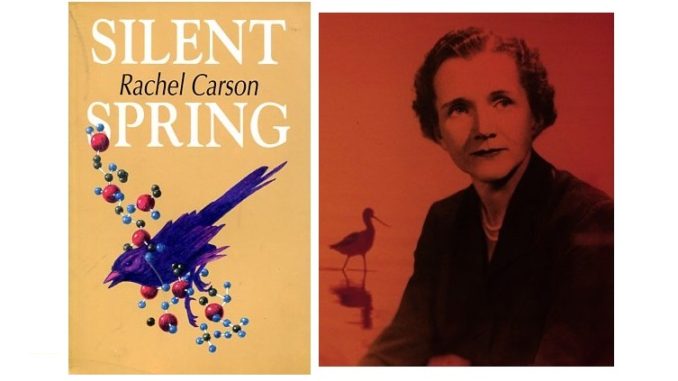

ver since I read Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring in 1963, I had subconsciously waited for something like Covid-19 to happen! The books prophesy combined with my own experience convinced me that, sooner or later, a war between Nature and Humankind was inevitable. And that is what Covid-19 is; a consequence of humankind’s ruthless exploitation, denudation and destruction of natural resources.

In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson describes an imaginary town, laid waste by excessive use of DDT, which was the leading insecticide used during and after World War II. It applied equally to other potent pesticides, developed later and also toxic pollutants, released by industries. But she enunciated a catastrophic withering of the vegetable and animal kingdoms first and through them, the destruction of humankind. Covid 19 on the other hand, attacked humans directly and humans alone.

To fully grasp this anomaly, we have to first understand Rachel Carson’s thesis. I start with quoting a short piece from her prologue, A fable for Tomorrow.

“There was once a town in the heart of America, where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings. The town lay in the midst of a checkerboard of prosperous farms, with fields of grain and hillsides of orchards where, in spring, white clouds of bloom drifted above the green fields. In autumn, oak and maple and birch set up a blaze of colour that flamed and flickered across a backdrop of pines. Foxes barked in the hills and deer silently crossed the fields. Along the roads, laurel, laburnum, alder, great ferns and wildflowers delighted the traveller’s eye, through much of the year. Even in winter, the roadsides were places of beauty, where countless birds came to feed on the berries and the seed heads of the dried weeds, rising above the snow.

Then, a strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change. Some evil spell had settled on the community: mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was a shadow of death. In the gutters under the eaves and between the shingles of the roofs, a white granular powder still showed in a few patches. Some weeks before, it had fallen like snow upon the roofs and lawns, the fields and streams. No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves.

“. . .This town does not actually exist; but it has a thousand counterparts in America and elsewhere in the world. “

Rachel Carson was a scientist, so she went on to explain in great detail, the damage caused by fusing and compounding chemicals to conjure new ones; which had a potency that was many times the sum of the original two or three. She covered every possible permutation and combination which was wreaking havoc on the balance of the natural system that sustained life.

Coincidentally, when I first read it, I had just married and moved from Delhi, a city of Babus and traders to an industrial township, Dalmia Nagar, in Bihar. It boasted of Industries like coal, cement, paper; limestone quarries for raw material and a steam railway line for transport of goods. As you can imagine, the air was full of cement, limestone and coal particles and it smelt of bleaching chemicals, used to cure pulp in the paper mill.

What I read and experienced, coalesced to shape a frightening vision of the future. I knew, a day will come, when Nature would take its revenge for being ravaged by pesticides and Industrial pollutants, plus the destruction of forests and wetlands by humankind.

My nightmare and the prophetic words of Rachel Carson came true, ten times in magnitude, in the middle of the night of Dec 2-3, 1984, when MIC and Phosgene gas leaked from the Union Carbide Factory of Pesticides in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. It turned Bhopal into a living replica of Carson’s imaginary town, covered by a poisonous white powder; where no birds sang and human beings were blind and dumb.

Instead of giving you details of the world’s second biggest industrial disaster, I want to connect it with globalization, by quoting a part of a story I wrote in 1985, called “Vinaash Doot,” which was a take on Meghadootam by the legendary Sanskrit poet, Kalidasa.

Let me first give you a gist of Meghadootam or the Cloud Messenger.

In the first half of Meghadootam, Kalidasa drew an environmentally researched, in-depth and detailed road map, for the cloud to travel from Ramgiri Hill in lower Himalayas to Kailash, its highest peak. It gave finely-etched details of the flora and the fauna, the changing direction of the wind and the climate; the different colours of the numerous rivers on the way and with them, the change in the colour and form of the cloud itself. He also described the opulent festivities of the towns and the erotic love life of the inhabitants. He insisted that the cloud not go straight to his destination; but make appropriate detours to savour the beauty, diversity and erotica.

Sounds familiar? Doesn’t Rachel Carson do something similar when she draws a pen portrait of the natural grandeur of her fabled town in the first half of her, “A Fable for Tomorrow?” In the second, she pictures the chemical catastrophe.

Kalidasa was fortunate. There was no catastrophe. That came centuries later in 1984. As he continued to live in a natural paradise, he went on to articulate a passionate and lyrical love message to the beloved in the second half. The crux of the poem was the intense yearning of the poet for his beloved, which made the impossible, possible.The cloud was the alter-ego of Kalidasa. The poet could travel anywhere he wished, because he was fancy free like a cloud, as only a poet could be.

Now, imagine a time, when the environment was totally polluted and destroyed by global Capital, carrying out secret experimentations, with poison without bothering about its lethal implications. Actually you do not need to imagine it because it was something that really came to pass in 1984, in Bhopal. When the poison gas leaked, killing and maiming thousands; all avenues of relief and rescue remained closed, because of the secrecy maintained by Union Carbide about the chemicals it had used. What would you expect to happen to love and passion then and to faith that had once made a mute cloud, its messenger?

![]()

The Cloud Messenger/Meghadootam. Ink drawing. Girijaa Upadhyay

I feel that under such circumstances, the cloud would not remain mute then but be forced to speak. And that was my story. Let me give you a short version of Vinaash Doot or the Rebel Cloud. It went like this:

“I shall not take your message to your beloved. I will not!” The cloud was quite adamant. The poet was shocked. Had not the legendary poet Kalidasa chosen a dapple grey cloud as a messenger for his love sick hero? Had the legendary cloud refused to carry the message, the classic Meghdootam might have never been written. The world that was then the third world but has now become the first or the only world, might never have heard of Bharat that became India. What was India without Bharat!

But here was a little fluff of a cloud refusing to obey him, he who was the re-incarnation of Kalidasa, born for the thousandth time, in the land of Kalidasa himself, in the very centre of India, that we now called Madhya Pradesh.

Brahmin that he was, he rose in terrible anger, all set to curse the cloud. But the poet in him restrained him. How could he curse the cloud and its progeny and deny the earth its meagre sustenance?

He contented himself with an admonition, “You cannot refuse to carry my message. By doing so, you are striking at the very root of poetry. What is poetry but the anguish and bliss of love? If you stand in its way, you would throttle all human passion and creative energy. From where would the cosmic dance of creation draw its rhythm and melody, its verve and fervour, its climactic orgasm?”

The cloud broke into derisive laughter.”Cosmic dance of creation indeed! What kind of poet are you that you can’t see beyond what seeing eyes show? Not eighty miles from here is the city of Bhopal!” The poet waited for him to go on but the cloud continued silent; as one who had nothing to say because the ultimate truth had been told.

The poet was puzzled and angry. He was not used to being puzzled. But he was a poet; his curiosity was greater even than his ego. He swallowed his pride and asked the cloud for clarification. The cloud laughed again.” Have you lost not only your vision but your sense of smell and hearing? Do you not smell the bittersweet smell of worm infested almonds? Do you not wonder at the sudden silence, that assaults the senses with far greater rapacity than the greatest cacophony of sound? This is not the dance of Lord Siva that carries the seeds of fresh creation in its womb. It is danced by the First World man, an imperfect being who believes himself perfect. Nature has not entrusted him with its keep. He has appointed himself the keeper, made a plaything of Nature and the third world his playground. He forgot that nature can strike anywhere.

“It was in Bhopal that it chose to strike. The affluent guised their arrogance and quest for knowledge in the cloak of benevolence, and taught the third world to kill the little creatures of nature, it called pests. Why did the third world agree! The arrogance of the First world combined with the carelessness of the Third, meant that the experimentation with poison, transcended crawling and flying insects, and struck at those who stood erect on two feet.

“What of my beloved, “mumbled the poet,” what news of my beloved?”

“Fie,” said the cloud, “Do you still hanker for news of her alone? What about hundreds of thousands….”it stopped mid-sentence, petrified. A sudden darkness descended upon the city. But its high noon, wondered the poet and why had the cloud stopped preaching? He went to the window and threw it open. The fleecy cloud rushed in. He felt its touch as it went past him…. An intense fire broke out robbing the poet of speech. Outside it was pitch dark. It was within his body that the fire raged.

As the fire reached his heart, his mind flamed with a last verse. “Give us grace, we shall atone.” He strove to give it voice so that the little cloud might record it for history… but he had no voice.

The poet died standing. He could not slide to the floor to cradle in the lap of mother earth. But as he succumbed, he felt the caressing touch of cool water on his face. With a last burst of extinguished hope, he realized that his rebellious cloud had the grace to weep over him, before it surrendered to the giant foe.”

What Rachel Carson could not foresee was the onslaught of viruses, which would single out human beings as their target. Covid-19 is a special high precision weapon, because it targets and impacts only humans, leaving the animal and vegetable kingdoms intact. The playground too thanks to globalization, is the entire world. As Covid-19 hit the world with full force, there was a regeneration of the environment. Not because of the Pandemic but because, human beings stopped encroaching on Nature. They kept to themselves, either in lockdowns or because there was closure or slowdown of Industries, factories, markets and traffic. One could safely say that an endangered and partially destroyed Nature had taken its revenge by unleashing the weapon of Covid-19, as it had earlier set loose MERS, SARS and Ebola etc.

But it is important to realize that Rachel Carson’s predictions came true. They did in the period between the unleashing of the viruses; by way of the disappearance of countless species of wild animals and birds. We also need to note that whether in gas hit Bhopal, nuclear bomb hit Hiroshima or nuclear leak hit Fukushima; Nature greened itself the very next spring. Despite the dire predictions of scientists, fruits and flowers of even unusual kinds blossomed. Only humans could not be resurrected. They were dead or maimed forever.

The process of breaking the barrier between the wild and humankind started, not with the outbreak of zoonotic diseases like Ebola, SARS, MERS, or Covid-19 but much before! All of us are equally responsible as it started, when every country started cutting forests and reclaiming sea area for land; for human habitation and construction of industries and roads, for rapid transport.

When speed became the new religion and technologies were geared for its worship, unmindful of the impact on climate and environment, it brought human species in closer proximity to Wilderness, reserved by Nature for the creatures of the wild. As a result, all of them clawed through the biological barrier between human and wild animal species.

The questions we need to ask ourselves are; would humankind learn its lesson and stop its rampant encroachment on Nature or continue the old way, once the threat is over? The people or governments of all Nations are face to face with this political question. But are they giving it serious consideration? Will something stupendous happen as a result of the current pandemic?

***

![]()

But first, let me to bring the story home to India. As one of those who had felt for long that the gang rape of nature was about to boomerang on the rapists, I was more anxious about the next generation than the current one. I worried about my children and grandchildren and the children of those rendered jobless, hungry and homeless by the country wide lockdown. The number ran into more than 300 million.

Who were those people?

They were that cursed breed of daily wage earners, peculiar to India called the migrant workers. Every year, poor farmers from all over the country, migrate to metros and Industrial towns, looking for work. What they get is daily wage work as contractual labour in factories and workshops, never mind that they form the bulwark of our Industrial production and urban services.

They were not allowed to go home to their villages, post covid, after a country wide lockdown was imposed by Central decree on 24 March 2020. No trains or buses were plying and the state borders within the country were sealed. Unbelievably, so desperate were they to go home to their villages and families that in the hope of making it, they travelled for hundreds of kilometres on foot. But they were turned back from the border of the next State they needed to cross. The State Governments’ plea that they were stopped to prevent them from spreading covid in the villages, defied logic because they had not yet contracted the disease! They got it only after losing their jobs and homes in the cities. That was when they were forced out on the roads in hordes to get the meagre free food, doled out by the govt and bit more substantial fare by private charities.

We talk of the great exodus from Germany before the 2nd World War or between India and the newly created State of Pakistan, post partition in 1947. The 2020 exodus was no less ghastly, though violence occurred not directly as blatant killing but circuitously through hunger. That was the new weapon which became universal in India in 2020. Actually it was not entirely new as we had a gory example in History.

The 1943 famine of India; in which more than 3 million Indians died in Bengal only, was caused not by drought but policy failure of the British Govt, that is, it was also violence through hunger. Lapses such as prioritising distribution of vital supplies to the military, civil services and others; stopping rice imports and not declaring Bengal, famine hit, were some of the factors determining the magnitude of the tragedy. Actually they were outward manifestations of an act of violence perpetrated by a Colonial Govt. against the colonised people.

What happened in 2020, post Covid-19 was another policy failure; this time by the National Government. Between January 30 when Covid-19 was declared of international concern and a countrywide lockdown on March 24; no organized plans were made for dealing with the known repercussion on millions of migrant labourers; who would lose their jobs and homes in the cities.

At last the lockdown was lifted on May 31, 2020 and the workers were allowed to go to their villages. But no proper amenities were provided for travel. Trains were run but they were not only few and far between but irregular, delayed for hours for inexplicable reasons and believe it or not, even losing their way. People had to crowd the stations waiting for them. More often than not, they went without food and water during days’ long journeys and there were quite a few casualties.

When the so-called migrant workers reached home after arduous journeys, they were put in quarantine for 14 days. The conditions in the quarantines were beyond belief. They survived the lack of food, water, ventilation and medicines purely because of their will to reach home, even if to collapse with hunger and exhaustion amongst the family. There were no jobs at home too, and hardly any food. The only work they could look for was under MNREGA scheme of the Govt, which gave a pittance in return for a full day’s work, and in any case was and is a temporary measure of relief. The reason they had left their homes and families was precisely because there were no jobs in the villages and farming could not support life. Now they were back in the same quagmire.

***

It comes as a pleasant surprise when historians affirm that the reaction by Indians, during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 was quite different. We were, of course, under British rule. When the rich businessmen and aristocrats, both Hindu and Muslim, called mohalledars, as they were heads of mohallas or localities, found that the government intended to do nothing to help the sick and dying Indian people, they took over the responsibility. It brought the Hindus and Muslims together, as had the First War of Independence of 1857. Both in 1857 and 1918, the motivation came from the need to fight a common enemy, the British rulers. It would be more pertinent to say that the fight was against an already prevalent racism, which separated the few British residents from the multitude of Indians so it did not fan any fresh brand of racism.

I want to quote from an article written on 24 April 2020, by Maura Chhun, of Community Faculty, Metropolitan State University, US. According to her, during the 1918 influenza pandemic, a staggering 12 to 13 million people died in India. But it did not strike everyone equally. Most British people lived in spacious houses with gardens and yards, compared to the lower classes of city-dwelling Indians, who lived in densely populated areas. Many British also employed household staff to care for them – in times of health and sickness– so they were only lightly touched by the pandemic and were largely unconcerned by the chaos sweeping through the country.

In his official correspondence in early December, the Lieutenant Governor of the United Provinces did not even mention influenza, instead noting “Everything is very dry; but I managed to get two hundred snipe so far this season.”While the pandemic was of little consequence to British residents of India, the perception was totally different among the Indian people, who spoke of universal devastation. In Mumbai, almost seven-and-a-half times as many lower-caste Indians died as compared to their British counterparts; 61.6 per thousand versus 8.3 per thousand.

India after 1918 never returned to normalcy of British perception. April 13 of 1919 saw the Nazi type massacre of Indians at Jalianwala Bagh by the British, with other atrocities in Amritsar and elsewhere in Punjab. Shortly after that came the launch of Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement. Influenza became one more example of British injustice that spurred the Indian people in their fight for Independence. A nationalist periodical stated, “In no other civilized country could a government have left so much undone as did the Government of India did during the prevalence of such a terrible and catastrophic epidemic.”

The long, slow death of the British Empire had begun. The dispossessed had risen.

*******

Mridula Garg (b. 1938) writes in Hindi and English. She has published over 30 books in Hindi – novels, short story collections, plays and essays – several translated into English. She was a recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Award in 2013.

Leave a Reply