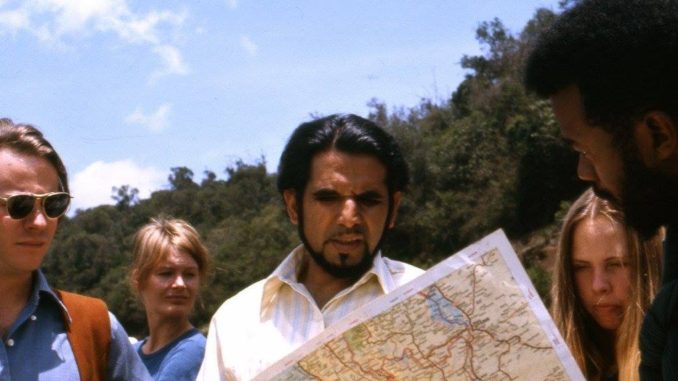

Kishore Saint with group of American students in eastern escarpment of Rift Valley Kenya

Kishore Saint

T

hese excerpts are from my memoirs about my work as a teacher educator in Kenya during the 1960s. This was a time of transition for Kenya from colonialism to independence (December 1963) and from social and political segregation to integration and indigenisation. Even before this came about I had opted to shift from Asian education to African education, first at Kagumo College, Nyeri in Kenya Highlands and then at Shanzu Coastal Teacher Training College north of Mombasa.’

Kagumo College Nyeri 1964

After independence education system in Kenya was being integrated. I came to know of an opportunity to teach in an hitherto African teacher training college, Kagumo College in Nyeri at the foothills of Mount Kenya at a height of 5500 feet above sea level. I applied to teach there and was accepted.

We reached Nyeri in early January 1964. I reported to the Principal, Mr Popkin and was assigned duties. To begin with we were lodged in a second grade house for clerical staff. This reflected the old hierarchical mindset of the Principal. Later when he realised my appointment as Education Officer he shifted us to a teaching staff bungalow. Most of the teaching staff were British but a few Americans and Canadians had come under the Peace Corps Programme. A couple of African faculty had also joined. Only other Asian staff was a physical education instructor, Roshan Lal from Machakos. With Master of Education degree and Postgraduate Diploma in Education, professionally I was the most qualified staff. I was asked to take courses in Teaching Methods, Educational Psychology, Approaches to Education. All the students were African, mostly from the Kikuyu tribe of that region.

They had good basic knowledge of English and had some experience in teaching in schools but the historical, cultural and conceptual background of modern systems of education was new to them. It had no relationship with their tribal way of upbringing and preparation for adult life. The curriculum in those days did not provide any opportunity for bridging this gap. I had read Jomo Kenyatta’s fascinating account of Kikuyu way of life in his book Facing Mount Kenya based on his doctoral thesis under Malinowski at the University of London. I had also read Elspeth Huxley’s ‘Red Strangers‘, a novel about the coming of white settlers in Kenya Highlands and how they were perceived by Kikuyu tribals. Despite being an outsider I took interest in students’ home conditions. During teaching practice we had to visit village schools to observe their performance. There we saw women at work, carrying fuelwood, digging, clearing land, drawing water, cooking, selling produce in roadside market.

In our teaching, however, there was no scope for local studies. Curriculum, text books etc had all been designed and prepared in the U.K. and had to be followed. Medium of instruction was English. Swahili, the lingua franca of East Africa, was taught as one of the subjects. The main course was of two years duration for primary school teaching. There were also short term refresher courses for secondary school teachers.

In extracurricular activities I led two climbing trips on Mount Kenya with the help of an experienced African guide. We took the route on the western side along Mackinder Valley named after the explorer, Harold Mackinder, who first reached the summit towards the end of the nineteenth century, starting from the base camp at Naru Moro. We traversed through thick equatorial forest, open deciduous belt, bamboo forest, coniferous trees, alpine grassland, ending at the snout of a glacier lined with weathered rocks. The highest peaks could be seen in the distance. The night was spent in a small wooden hut tucked in sleeping bags with temperatures well below freezing point. Next day getting up early we walked some distance on the side of the glacier toward the peaks reaching a height of 15000 or so ft. Climbing the peaks needed special equipment which we did not have. We returned the same day to the base camp and took the bus to Nyeri. As a part of my geography teaching I organised field visits to tea and coffee plantations and factories.

Among some other memorable events was Kenya’s President Jomo Kenyatta’s visit to Nyeri. This was a huge gathering of mainly Kikuyu tribals dressed in their ochre wraparounds. They occupied the main streets up to the shop fronts where we stood with our cameras to get a glimpse and photo of the great Mzee who had led Kenya’s freedom struggle spending many years in jail. He arrived, standing in an open sedan car smiling and waving at delirious crowds with his monkey tail hair whisk. Kikuyu women greeted him with their traditional ululating sounds. He made a short speech in Swahili encouraging people to unite and work hard for the progress of the country. Despite large numbers there was no chaos. But the wife of one of our Canadian colleagues found the heat and crowds exhausting. She nearly passed out. Later talking about the experience she described it as being in the midst of a mass of creepy, crawling creatures. Clearly, she had yet to feel the human in the people her husband had come to work for.

SHANZU 1967-68

This new institution had been recently constructed on an old raised coral reef along the coast. As first constructions on the site the buildings and houses had a modern design and were made entirely of cement concrete. We were first allotted a single storey two bedroom quarter with ground level vents in the walls. All home facilities had to be set up from scratch.

As at Kagumo, the College had a multiracial staff with British, American, Asian and African backgrounds. The Principal, Frank Bentley, recognized this and gave space and support to everyone. Since it was a new initiative in two years full time teacher training for primary education, every aspect -curriculum, schedules, teaching aids, textbooks, library, extra-curricular activities – had to be planned and organized from scratch. An academic staff committee was set up chaired by the Principal. Mr Bentley asked me to be the convenor. This was exciting work which gave me an opportunity to introduce new ideas and content. It was also a challenge to take into account and integrate the views and suggestions of staff with diverse backgrounds.

Amongst the topics I introduced in educational psychology was child development. I did this by encouraging students to observe their own and neighbours’ children at different ages and record the changes. However, my most ambitious undertaking was a local study project involving all the staff and students for three weeks on full time basis. This is how it came about.

In 1967 it was decided to introduce a three term pattern for the academic year. This was to be done in the middle of the year. The change left us with a three weeks gap in which something had to be done to keep staff and students engaged. I suggested devoting this time to study the region the College was located in a systematic way. A sub-regional framework was visualised starting from the sea in the east and extending through coral reef, beach, fossil reef, floodplain to the low hills in the west. These north-south strips had to be studied by the students on an inter-disciplinary basis, both in the field and through library work. This was to be done in a project format guided by the staff. The main subject areas for study were geography, history, science, mathematics, social studies, economy and culture. Students across classes were divided in groups and sub-groups keeping this matrix of sub-regions and subjects in mind. The first week was given to library work and planning. This was followed by nine days of field work. During this time students talked to local farmers, fisherfolk, factory workers to learn about their occupations and culture. They collected samples of crops, fruit, crafts, shells, coral, rocks. Those with a camera took photographs. Others drew sketches and paintings of what they saw. The concluding five days were given to writing reports, sketching, making charts, hanging displays for an exhibition of the work done.

The editor of local English newspaper Mombasa Times was invited to inaugurate the display. He was so impressed he wrote an editorial in next day’s edition applauding the effort and recommending it as a creative approach in education. I suggested to the Principal to invite practicing teachers from schools to come and see the work and have a discussion on it. For some reason he did not agree and the display was taken down next day. However, staff and students in general appreciated having this opportunity to work together and get to know each other and the locality better.

***

Teaching High School in Kisumu, Kenya

Prem Saint

D

uring my flight from London to Nairobi, in August 1960, I am excited to go home, and yet I am unsure where that home will be. I was awarded a Kenya Government scholarship in 1955, to study in England for five years for a Bachelor of Science degree in Geography and Geology. Now, I have graduated, and I am ready to teach in a Kenya high school.

I pull out a map of Kenya and contemplate the possibilities where Mombasa, my hometown on the east coast. Or, Nairobi, the capital, or Nakuru, in the Rift Valley, or Eldoret, in the western highlands. May be it will be Kisumu, on Lake Victoria. My father has been teaching there and has been talking about retiring. May be he will be helpful.

I reach Nairobi, and I sense a palpable wind of change blowing through the city. A number of new buildings have gone up, and the automobile traffic has multiplied. There is a lot of uncertainty about Kenya gaining independence from the British rule. I have learnt to keep a low profile in political matters, and to go with the flow. A few days after landing in Nairobi I am summoned to the Kenya Education Department, to meet with the Assistant Director, Mr. Amar.

“Welcome home, Mr Saint. I hope you have learnt a lot in England, and are now ready to inspire our high school students. We have a vacancy for a Geography teacher in Kisumu. How would you like to go there?”

“I do not know much about Kisumu, except that it is located on Lake Victoria. What kind of a high school is it, Mr. Amar?”

“Well it is a small Indian high school. in a predominantly Indian town. I was a Principal there a few years ago. The parents are very supportive. You will like it Prem Saint, July 2019 there.” “Ah, well….?” “ Please report to Mr. Sood at Kisumu High School in two weeks,” he adds, ignoring me. And that is that. Under the British colonial system you go where you are sent.

Mr. Sood, the Prinicipal, is much more friendly. He shows me around the school and introduces me to some of the teachers, who are friendly and welcoming. Back in the Principal’s office, Mr. Sood wants me to talk about my scouting experiences in England.

“I understand you underwent advanced leadership training for scoutmasters. Can you help us with our Boy Scout Troop?”

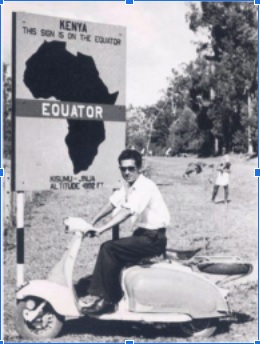

I am delighted to brag about my favorite subject. “Yes, I took several leadership courses at Gilwell Park, and was awarded the Wood Badge, I visit the Equator near Kisumu, in September 1960 their highest badge. Also, I worked as a camp counselor one summer in America. I’ll be happy to work with our school Boy Scout Troop.” Now, I am also the Scout Master of our Troop. And find out that our troop has no outdoor equipment, other than some ropes and a few wooden hiking sticks.

I present my dilemma to our four patrol leaders and our troop leader.

“No problem, sir. We have many contacts among our parents and friends,” assures Karam Singh, our Patrol Leader.

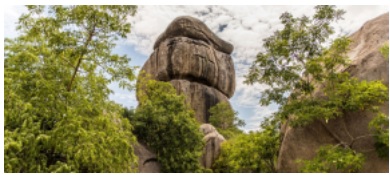

Our scouts are keen to go camping and hiking. One of our Patrol Leaders, Iqbal, suggests a hike to the Monkey Stone, the highest point in the nearby Nandi Hills. He also knows a sugarcane farmer on the foothills, where we can camp. Another patrol leader, Shirish, makes arrangement for transportation. The father of Sadiq, one of our scouts, works for the Kenya Survey Department, and he can loan us some tents. Finally, we are ready for our first weekend camp. Yeah… !

Karam Singh, takes charge of the shopping and cooking arrangements. I am impressed with the initiative displayed by our scout leaders.

Our campsite is a clearing on the sugarcane farm, which is surrounded by a rainforest. After dinner, we have a campfire, where the Punjabi farmer and his family join us. Our campfire songs are a Satellite image of Lake Victoria’s Kavirondo Gulf, where Kisumu is located mixture of English, Swahili and Punjabi lyrics,. These are interspersed with the howling of dogs and of the deer. Fortunately, the mosquitoes are kept away by the blazing fire.

Next day we hike to the Monkey Stone, carrying our lunches and water. We also carry pangas (machetes), for clearing the overgrown trail, and ropes for the final assault. During our hike we meet some impala deer, and see many colorful birds which I had never seen before. During lunch at the base of the Monkey Stone we devise a plan for the final climb. Some experienced scouts reach the top, carrying strong ropes. At the bottom, I teach the other scouts some knots to create secure chair loops. These are used to haul the younger scouts up the steep slopes. On reaching the top, our scouts savor the moment of triumph. We are enjoying the panoramic views of Kisumu and of Lake Victoria. For me this is a fascinating introduction to scouting in an African setting, where there are few developed campsites, but a lot of improvisation. I welcome this challenge.

For my Geography classes, we organize field trips to the Kenya Rift Valley, in the east. and study the faults and the volcanoes, Also, we visit Jinja, in Uganda to the west, to look at Ripon Falls, with hydro-electrical power station on the Nile River, and the sugar mills nearby. Again, the students take the initiative, by contacting their relatives and family friends, for transportation and accommodations. Wow, what a contrast from my experience of field trips and camping in highly sanitized sites in Britain and the USA.

In December, 1961, I get married. I want to showoff my excitement about living in Kisumu to my bride who is from Nairobi. We visit Hippo Point on Lake Victoria, to watch the sunset and the hippos, and to enjoy tea and samosas. Suddenly, we are attacked by mosquitoes, and we make a hasty retreat. Next day I complain about this incident to the owner of the teashop. Sure enough, within a week, the restaurant has a covered, screened area, free of mosquitoes. Later, when our son is born, we move to a larger house near the lake. Every evening impala deer came, and graze in our backyard. We love place to commune with nature.

In 1965, after earning my Master’s Degree, I am transferred to the Water Development Department, in Nairobi, to work as a hydrologist and a hydrogeologist. And that brings to an end to my high school teaching. I am still in touch with some of my Kisumu students, and we reminisce about the High School, the Monkey Stone, the Hippo Point, and laugh about the pesky mosquitoes.

*******

Kishore Saint was born in Peshawar. Following Partition he migrated to Kenya where, after a spell of studies in the United Kingdom he worked as a teacher and teacher educator. He spent a few years in the USA working in Friends World College, an experiment in World education. He returned to India in 1972 for good. As an activist he has been involved with rural tribal communities in South Rajasthan on problems of environment protection and regeneration in relation to livelihood. He is currently working on his memoirs.

Prem Saint Ph.D. is a Professor Emeritus, Geology and Hydrology, at the California State University, Fullerton. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota and an M.Sc. and a B.Sc. from the University of London England. Apart from teaching in a Primary and a High School in Kenya, Dr. Saint was employed as a hydrologist and a groundwater geologist for Kenya Ministry of Water Development. After completing his Ph.D., he was hired as a Professor at California State University, Fullerton, in Southern California. He has worked on State and Federal Projects on Water Pollution Control, Hazardous Wastes and Constructed Wetlands. In India, he has undertaken pioneering fieldwork on the Ghaggar River in Punjab and on the watersheds of the Udaipur Lakes in the Aravalli Hills of Rajasthan. He has published several research papers and consulting reports on projects in Kenya, California and India.

Leave a Reply