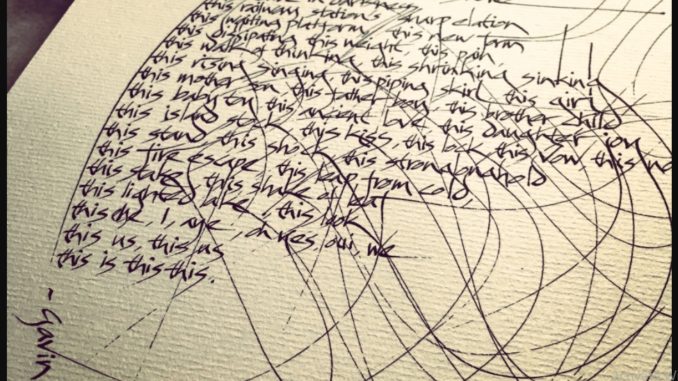

Calligraphy by H. Masud Taj of Gavin Barrett poem “This Fall

Gavin Barrett

Gavin: Taj, as Bombay poets both, you and I have shared poetic space on many a page over the years, and at the same time, a great deal of your poetry has been oral poetry— what the world today calls Spoken Word — and I hear that it took some haranguing to commit your oral poems to paper finally. So Taj, tell me about the challenges and joys of your oral poetry. Why oral poetry, and why did you need to be convinced to get it printed?

Taj: I think it’s got to do with the process. The way I do a poem is all in my head. Meaning from the moment of inspiration until it ends up as a crafted poem, it is all in the mind. It may take 20 minutes or it may take four hours. And once it is finished, you leave it there and recall when you need to. I can’t take credit for this because this is something that came naturally to me. When I reflected on that, I realized this is how all poetry began. Because the origins of all epic poems in every language are oral—writing came much later. And I thought, well, it appears the oral poet has been born again!

And to be true to my calling, putting words to paper is a fall from grace. Now, this is paradoxical because I am also a calligrapher, and when calligraphy appears in my poetry, it is always in a negative sense. For instance, in the poem “Vampire”, there are two stanzas.

They say blood is red

But by the residual light

Of moonless night

All blood is ink.

Punctuations are punctures,

I am a lapsed calligrapher

Who does not inscribe

But reverse-flows ink.

Or you have the calligrapher as a serial killer whose blade is a “stainless reed.” This goes way back to 1991 when The Silence of the Lambs was running on Sterling Theatre’s 70 mm screen with Dolby sound. The next year, this villanelle was published in Debonair—so, arguably it is the earliest, if not the first, classic villanelle in my generation in India. At the same time, Debonair also published my avant-garde work—pieces like the Zipper poem. You read the whole poem, and then you unzip it, so it becomes two strands you read separately. But let me recite “Killing & the Art of Calligraphy” for you.

He leaves his signature on the skin,

Glint of the moon on stainless reed,

With inkless stylus draws out ink.

He can stare for hours and not blink

At bodyscapes to get a lead,

He leaves his signature on. The skin,

Tabula rasa for his sin,

Compelling inscriptions he pleads

With inkless stylus. Draws out ink,

He sees the red run in the sink.

Water is a part of the creed

He leaves. His signature on the skin:

Snake devouring its tail in a spin,

Ending is a beginning seed

With inkless stylus. Draws out. Ink

Trapped in a loop mode he dare not think

Of life and art and death and deed,

He leaves his signature on the skin

With inkless stylus, draws out ink.

Gavin: “Trapped in a loop mode he dare not think / Of life and art and death and deed, / He leaves his signature on the skin / With inkless stylus, draws out ink.” That paradox, that beauty, thank you for sharing that poem with us. I have to ask you: I know there was a poem you recited as a finalist at Scream in High Park one year — I believe it was the year you landed in Canada? You recited a poem on that occasion. What was that poem?

Taj: Actually, that poem landed in Canada before I did. Someone read it on my behalf; yes, it was a finalist at Scream in High Park in Toronto. It was The Cockroach—one of the 90 animal poems in my Bestiary. The scene is that you are sleeping and feel something crawling up your sleeve, back in India. You wake up in a panic, you jerk your hand, switch on the light and there’s a big cockroach sitting on the edge of your bed. You take a newspaper and whack it! Now, the thing is this; I recall distinctly, mid-whack, I hesitated. I hesitated because it did not run and that perplexed me. We are opposing species: my job is to whack you; your job is to run. Why didn’t you run? I couldn’t sleep and just like Kafka’s metamorphosis, I think I metamorphosed into a kind of cockroach! By sunrise, the cockroach was speaking.

I wait on the hard edge of his bed,

Watching the blur of newspaper

Rolled into a taut cylinder

Arcing towards me.

Species are forever, I shall not flee.

Survival, after a while, is tiresome.

Individuals must, once in a while,

Learn to let go.

The cylinder is approaching

At an unnecessary speed, driven

Less by the need of the moment,

More by his fear of machines.

My glinting bronze exterior

Belies an inner yielding;

He is soft outside, hard within,

But bones only wrap around voids.

I am supremely articulated,

My structure is my ornament.

He is a blob with a brain and four limbs,

One of which he is swinging in.

The aim of all his existence

At this instance is to snuff out mine.

He does not know, even as he does so,

He is bending to my will.

Close up and the greyness of the cylinder

Separates into patterns black and white.

Zooming in, black explodes into planets

In panic fleeing white space.

And then I am touched by the cylinder,

Knighted I shall arise in a new age of bronze,

Oh the sweetness of surrender that ignores

The crushing weight of a mind once set.

My sides burst symmetrically –

Is there life after death?

Is there death after life after death?

Is there life after death after life after death?

Turn to the back page

Of yesterday’s newspaper:

I am a Rorschach smear in relief.

Read me.

Gavin: I have to confess that is the first time I have ever liked a cockroach!

Taj, you write extensively and capaciously in English, though your mother tongue is Urdu.

Could you tell us something about what your multilingualism has meant to your life, to your poetry, to your work? What doors has it opened for you?

Taj: Yes, my mother tongue is Urdu; my Muslim tongue is Arabic; Indian tongue is Hindi, but I grew up in English in Blue Mountains School, in the southern mountains of Ooty where we heard Carnatic songs in classical Tamil—and I am fascinated by the sounds and script of each.

My heart is in Urdu, my head in Arabic, my tongue in English.

So, when the longest-running annual mushaira in Ottawa, celebrating Sir Syed Day, invited me, an English poet, to preside over their Urdu poetry evening, I chickened out. Now, I have faced challenging audiences—uniformed officers of the Indian Navy at a naval base in Bombay or a lone Bosnian refugee in Vienna’s Landtmann Café—but Urdu audiences are astute, and they are unforgiving if you slip up. If you are not up to the mark, you’ll be booed into oblivion. My strategy was to begin with an Urdu ghazal by my father.

Abhi na ja o saaqiya

Abhi na ja, Abhi na ja,

Zara idhar, idhar to aa

Abhi na ja, Abhi na ja

Abhi to raat baqi hai

Abhi sharab saqi hai

Peelai ja, peelai ja

Abhi na ja, Abhi na ja

It goes on in this vein, in the same beat

Janam se mein kahan kahan

Zaman zaman, makan makan

Teri talash mein phira

Abhi na ja, abhi na ja

Once I had set the mood and established my Urdu credentials, I segued into my bilingual poem, and that’s the one I’ll recite now. It’s called “Fade-Out”. It’s an old poem, but it is so apt today. Because, Gavin, even as we speak, people are dying. This pandemic is unrelenting. And what is tragic is that somewhere they are dying needlessly due to the ineptness of the very people they elected. So I guess the poem’s message is, “Hang on!”

The leaf that defied the season

Was the leaf that decided to stay

Woh sab guzar gaye.

Hand that clenched into a fist

Was the hand that opened to pray

Woh sab guzar gaye.

Eyes that beheld the rising sun

Closed at the close of the day

Woh sab guzar gaye.

Life that knew all along

It was death at the end of the way

Woh sab guzar gaye.

Gavin: Beautiful. How would you render Woh sab guzar gaye for readers not conversant with Urdu? What would be your preferred translation?

Taj: I wouldn’t because if I did that, I would have to translate English into Urdu, and you’d be left with the same predicament.

Gavin: Very true! We’ll let our readers look it up for themselves. Taj, you and I are both immigrants from that incredible port city, Bombay. We even come from the same idyllic part of it, Bandra, with its face always turned to the setting sun and the shining sea. Maybe that orientation gave us our wanderlust; you and I have travelled extensively as young men, and we seem to keep travelling even in our later years. I don’t think I’d be stretching it if I were to say that these have always been journeys of discovery, exploration, pilgrimage even, and as much internal as external.

My last question for you is a travel or rather a pilgrimage question, and I will deliver this question to you in verse—much as you have been answering in verse. This poem of mine, called “This way to the sangam”, comes from my book Understan, published last year by Mawenzi House. I’d like you to answer the question in the last line of the poem with any poem of your choosing. Here’s my poem-question.

This way to the sangam

By the sea I met a man

out walking a holy elephant,

firm of foot

headed south.

Walking with him a length, we spoke.

Sounds fell from his mouth,

rounds of sand sank into the beach

beneath the animal’s shuffling feet.

He confessed his journey was to the temple of the north

where even now a million men drew near

before the crowds arrived.

But he was going south I said.

He shrugged his nothing and read

my curious face, my foreign speech

considered his slow pace, this white beach.

Would he not be late?

But what good was any pilgrimage if it ran straight?

Taj: That pilgrim, on his way to sangam, I think he lost his way. Because when I found him, he was humming under his breath:

Bol raadha bol sangam hoga ki nahin

He also lost his elephant! Because he was sitting cross-legged, by the shore of Marine Drive. So I photographed him and put him on the last page of my illustrated monograph on the city Bombay which got lost in Mumbai: Walking Looking Thinking: A Pedestrian Views Public Spaces in Bombay. He is under the Author’s Note—the book is full of illustrations and he is the last illustration.

A decade later, I found that lost elephant in the mind of the Canadian architect Arthur Erickson on the stage of the National Gallery of Canada. We were having a conversation and I asked him what he would like to be reborn as? Not quite the question he expected. He grew silent, and then he said, “An elephant.” So I recited my poem “Elephant” for him.

Inarticulate

Blob of ink;

Nose and tail

Out of scale,

Ears that would be

Wings.

White tusks precede

The body’s darkness

Scanning eyes

Record the world.

Mind does not erase,

Does not overwrite;

Celebrates the excess

Of memory

With the memory

Of excess:

No bigness

Is big enough

When you have

Forgotten

How to forget.

But your question was: But what good was any pilgrimage /if it ran straight? And you do realize you are asking someone whose dissertation Doctoring Strange Loves, was on constructing the labyrinth using the movies of Stanley Kubrick.

At the end of last year, I was deluged with a hundred poems, literally a hundred poems on ordinary objects in the house. Zeba says that’s what happens when you lock down a wandering poet.

Typically, the day would begin during breakfast with Zahra, my delightful 12-year-old, saying, “So daddy, what about the flower-vase?” And I would look at the flower-vase in the room, and it would speak to me. Or Nuh—Noah—my son would drop in and say, “What about a three-point socket?” or something like that, and I would look at one, and the words would come. One of them was the paperclip, itself a micro-labyrinth, spiralling with three U-turns that make up 540 degrees (as in a pentagon). Here is my “Paperclip” agreeing with your pilgrim.

Life moves

In a roundabout way

You end where you began

Displaced

Begin inside

End up outside

Begin outside

End up inside

Begin inside

Descend before ascending

Then descend a mighty descent

Before ascending to the level you began

Begin outside

Descend before a mighty ascent

Then descend less than before

Before ascending to the level you began

Sum total of all your ascents and descents

Is a sideways shift

Inside to outside

Outside to inside

All pathways end

At the same level

You end where you began

Displaced

Gavin: A labyrinth hidden in a paperclip; this is the poetry of H. Masud Taj.

*******

Notes Excerpts from Howl, the literary radio show on the University of Toronto’s radio station CIUT89.5FM. You can listen to it in full on Soundcloud at https://soundcloud.com/gavin-barrett/howl-ciut895fm-hosted-by-gavin-barrett. Cover image photo by Gavin Barrett.

Gavin Barrett is a poet and the author of Understan, a new collection of poems published by Mawenzi House in June 2020. Born in Bombay, India, of Anglo-Indian and Goan East African parentage he lived in Hong Kong for several years before immigrating to Canada. In addition to Understan, Gavin’s poetry has been published in Ranjit Hoskote’s anthology of 14 contemporary Indian poets, Reasons for Belonging (Viking Penguin, India); the journal of Pen India; The Folio; The Independent; The Toronto Review of Contemporary Writing Abroad; and Poeisis — the journal of the Bombay Poetry Circle. He is the founder, host and series co-curator of the Tartan Turban Secret Readings, a Toronto reading series that focuses on giving BIPOC writers a stage. He is the co-founder of Barrett and Welsh, a branding and advertising agency that creates inclusion through communications.

Masud Taj poet, calligrapher and architect grew up in Bombay, hearing Urdu poetry at dinnertime conversations. He is an award-winning Adjunct Professor at Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism and lectures on Muslim civilizations at the Centre for Initiatives in Education, Carleton University in Ottawa. He is the architect of War Memorial in Bombay, was mentored by Hassan Fathy in Egypt, worked with Charles Correa in India and conversed with Arthur Erickson at National Gallery of Canada. His book Embassy of Liminal Spaces synthesizing his poetry, calligraphy and architecture is a permanent installation at the Canadian Chancery, India and has been inducted into the Library of Parliament. His book on Frank Lloyd Wright’s apprentice Nari Gandhi is archived in the University’s Special Collections and his poetry collection Alphabestiary featured at the International Festival of Authors, Toronto. Taj himself featured in Portraits of Canadian Writers, on TIME, CBC and BBC. His writings on the website Academia can be freely accessed at https://carleton-ca.academia.edu/HMasudTaj

Leave a Reply