Darius Cooper

P

icture this:

A chawl in Poona. 2394 Sholapur Road. Where Pool Gate begins. The Sindhi resident who lived above Prince Restaurant never learnt Hindi. He spoke only a Karachi Sindhi. All his daily transactions were done instinctively. He had taught us how to deconstruct his gestures. He found all languages unnecessary. Next to him was old Mehra-mai. Her tiny home was daily populated by the Kasees and the Raibais who came to Poona from their gaons looking for work in the cantonment’s middle class homes. In their presence Mehra-mai spoke only in Marathi. When she didn’t want them to hear what she was saying, she spoke to us, her Parsi neighbors, only in English. She had devoted her entire life looking after her insane brother Dinsa-ji. He was a gentle soul constantly addressing his lunacy, but always in English. In our tiny home, we spoke, hesitatingly a fractured Gujarati, but if we didn’t make sense, we quickly corrected our broken bols with English. With our female bayees we communicated in a footpath Marathi, the kind spoken in the Bhimpura Lanes where they resided. I called it, to their delight, a yere yere pausa Marathi. Our matriarchal Iranian landlady, Banubai spoke Dari, Gujarati, and an explicit madar chood Hindi, especially when she called her Muaa Kasam, Prince Restaurant’s regular bharwalla, to get her endless cups of chai, buns, and bread pudding, but the summons were always affectionate and her stream of Hindustani galees humorous. Her daughter Homai aunty and her grand-daughter Katy, who went to St. Helena’s, always spoke English, never saw Hindi films (they were too phaltoo) read Romance novels and watched only Hollywood films. However, in spite of all their stubborn Anglo Indian efforts, the Hindi film argots did creep in. This is how Rohinton, their son, who went to St. Vincent’s, chipped in, after we had both seen Shane for the third time. “Tereko maloom hain? Sala Alan Ladd never used a double in his long fight scenes. He insisted on actually fighting. Soowar to tha, but still he was a man!”

I went to a British School, Hutchings High. Our English medium of instruction for all eleven standards came all the way from London. Our funding, however, came from the religious Methodist Churches in America. So we met Jesus and his apostles and all the saints from both testaments, in the wonderful King James English translation of the Bible, and we were mesmerized by all the English fictional heroes and heroines we read in our exclusive Radiant Reader texts. I always insisted on buying the English publication and mocked the cheap Tarachand Bookseller’s copy that was offered as a substitute. There were only three British Schools in Poona. Ours (which was co-educational), Bishop’s (for boys), and St. Mary’s (for girls). We were all being prepared to eventually face “higher English studies” and land up in Oxford and Cambridge via our school leaving prestigious exam called the Senior Cambridge or the Indian School Certificate exam. We always ignored the ISC title and called ourselves the Senior Cambridge Scholars.

Read Here: Geetanjali Shree, “growing up in Two Tongues”

Hence, the establishment of the predominant colonial binary even after the goras had left. Everyone and everything angreezi that came from academic England and an entertaining America was considered privileged. All Indian sources, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, were considered inferior. We lived in a Platonic Universe, where the Idea was defined always in its English language-determined affiliation even when it was so remote. The Indian version may have been more intimate and more comfortable, but it was always marginalized. So, we laughed and loved Falstaff and how he was made into a buffoon by Hal at Shrewsbury. But we were bored and irritated when Mrs. Pathole, our Marathi teacher, talked about how Tanagi used a large lizard, the ghorpad, to climb Shivgad. We enjoyed the “tally ho” refrains in Shammi Kapoor’s baar baar dekho/hazar baar deko” song because, in addition to punning on the words to invoke taalees or applause from the audience, it also implied primarily the English huntsman’s resolve to triumph in the hunt. Sure, dada Burman’s provocative “ek ladki bhegi bhagi si” was very infectious, but the original from which it was borrowed, Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Sixteen Tons” was far superior.

What certified this colonization in our psyches was also the iconoclastic roles played by our Marathi and Hindi teachers. We were not allowed to enter their vernacular universe, because they, and not us, did not want it. They displayed an overt hostility in the classroom and constantly scolded and ridiculed us for our English/American presences and preferences. When I told Mr. Deshmukh, our Swadeshi clad Hindi teacher, that I knew what life in the Indian villages was all about because my father was a Permanent Ways Inspector for the Indian Railways, and was constantly posted in villages like Dudhni and Kurduwadi, “names,” I said, “you can’t find on the map of India in our Atlas.” As soon as he heard that, he pounced on me, “Why are they not on your English map of India? Did you ever sit down with a shetkari and have Javari bhakar and looncha? No, you carried it and ate it from a plate on your English dining table in your bungalow. And why are you telling me all of this in English?” When we tried, however, to pose questions in our broken down Hindi, he would retort, “Yeh shbda galatt hain. Bheje sein aasli shabda nikalo.” The “til gul gya/gaudgaud bola” Marathi met with the same nativist response. We were tragically orphaned from these two beautiful languages and so much was lost because of this hostile kind of binarisation that still exists and is demonstrated today by the natives. The teachers in college were ever more perverse. Our Hindi teachers would add to our confusion by lapsing from Hindi into Sanskrit and refuse to translate that into English. It was the same even with some of our old English teachers who would plunge into Latin to explain something Milton wrote without giving us the English version.

When I wrote my critical study of Satyagit Ray’s film in English, most Bengalis hated it. They refused even to read it. “How can you write about Ray’s films when you don’t know Bengali?” This question was always addressed to an Indian, but never to Ray’s English and American critics. Tired of this constant accusation, I singled out one nasty gentleman.

“You are, I presume, being Bengali, well read?” After he had argued I proceeded to point out, “Then you must have read Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, and Flaubert and Balzac, and I notice you are carrying the poems of Pablo Neruda and Octavio Paz. So, am I to presume, you have read and understood them only in Russian, French, Spanish and Mexican, the languages they were written in and not in their English (or Bengali) translations?”

Critical Imperatives

The desire to be bilingual (or even trilingual) was always there, surrounded as one was, constantly, with people who spoke in so many fascinating and different tongues. But, it was never reciprocated. The nativism of the regional language always protested and barred the English entry. Then it mocked it, refusing to yield the grandness of the vernacular in which the meaning to be conveyed was wrapped in. We were literally out-casted as “the Wren and Martin” generation. The response was always punishing and incestuous The image of the colonizer that our facility with the English language constantly projected was never obliterated. You were reduced, and not just in linguistic terms, to the other. So, it was not a question of me choosing English “by accident.” It was English, rather, that chose me “historically” when I was exiled, repeatedly, from these vernacular ‘edens.’ If I did balance, and at least, dared to speak the vernacular from time to time, it was only in a mimetic vein that, as I was constantly reminded, was always thrice removed from the ideal. So, with my Marathi friends, I always referred to their fathers as vadils, their mothers as aiyees, their brothers as bhaus, and their sisters as taees. Similarly, in a Muslim, “mohool, Urdu “manzils” were awkwardly “ghazaled,” these efforts always brought on a smile, which was then followed by the “Koshish Karte rahoon” sermons.

English, the only language that determinedly adopted me, in my homeland, turned out to be wonderful. It was, first of all, very inclusive. One could include many other mother/native tongues with it, in what Rushdie calls, chutnification. (This is what I have been doing in this essay as well.) If one is writing a story in English that is taking place in a Maharashtrian wada, or a Kamatipura brothel with Amijaan as madam, or a Parsee library, the encrusted languages of these sites would always spontaneously creep in, and you did not have to offer footnotes in English to explain them. This kind of otherness is acceptable. It is,, in fact, magical, and you can feel the wholeness of understanding the source language when it is sensitively translated into English.

Tukaram’s “abhangas” gracefully ascend from Vithal’s feet and joyfully embrace your consciousness in Dilip Chitre’s marvelous English translations. So do Kabir’s “dhohas” in Linda Hess’s bhakti efforts.

Geetanjali Shree condemns the power of English to globalize its overwhelming importance, thereby marginalizing Hindi. But this is not done in any way to inferiorize it. It is done because English, unlike all other languages, has worked very hard and succeeded in earning, not just a local, but a global acceptance, making the important process and idea of communication, transparent and clear. Speeches in the United Nations or at important ceremonies like the Nobel Prize, are always made in English. Earphones are given if you wish to hear them in the original language. But here, the vernacularization is privatized. The English version is offered publically, for universal understanding. It is like watching films, in their own languages, from different parts of the world, with English subtitles. If one had to watch them dubbed, they would become laughable. The English subtitles do not interfere with the culture’s vernacular, and as one enters the film, one understands its native contents without the English subtitles guiding one to its meanings.

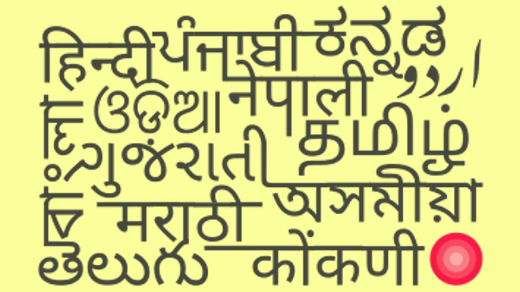

My response to Shree is we should abolish and not participate in the center/margins binaries. A concerned effort has to be made to reach out and welcome all “others” to such an extent that the exclusive idea of the “other” itself is not acknowledged as “the other” at all. Scripts of languages vary, both in their spoken and written forms, but the meanings they convey are identifiable, beyond language, as one composite whole. So why this binarization?

I offered this in my own instinctive way when I was a child to one of my best street friends who was Hare Moochi, our cobbler. When he came, every “morning” to polish our black and white shoes for school, I offered him Marathi “a sakaal” greeting. On weekends, when I passed him by in “the afternoon,” I always threw him a “dupari” greeting. Coming back from school in the “evening,” I shared “a sandhyakaal” one. And he always came and told us “goodnight” before he left for home fondly clutching “the ratri” greetings he would share from us with his family. In this exercise I tried to include, and not exclude or compare and contrast the native Marathi and the English utterances, so that neither of the two languages began or ended, thereby escaping out any emerging presences, either of the center or the margin. This is what living in the language, any language, really means.

What one has to be constantly aware of is not committing the sin of essentialism. The English generation does that. But so do the nativists. The wombs of all languages hate it. By calling “a father, a vadil,” I am not implying a specific cultural patriarch or a heavenly figure but embracing all fathers through an intimate bonding of more than one language. If I indicate that all of us are embarked on our “manzils,” I’m not implying the narrow meaning of “destinations,” but the universal one of “goals.” Each tongue should express not just a singularity, but a totality of understanding gained always by several inclusions. The overwhelming specter of just one power should never be allowed to raise its ugly head in any language. Henry Higgins had no right to infer and correct the flower girl’s authenticate cockney utterances.

She pretended to be a Duchess at the Epsom Derby when she danced, ate her cakes, and sipped her tea. But when the horse she bet on lagged behind, she told him in definitive cockney terms “to move its bloody arse.” Did Higgins even bother to attend the girl’s father’s marriage and then salute him only in his cockneyed terms, at the bridegroom’s favorite pub?

The time has therefore come for Hindi to remove all its caste marks, and for English to welcome it and embrace it without, and in spite of, the proverbial white talcum powder.

********

Darius Cooper taught Critical Thinking in the Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, California, USA. His essays, poems and stories have been widely published in several film and literary journals in USA and India A sample: Between Tradition and Modernity: the Cinema of Satyajit Ray (Cambridge University Press).In Black and White: Hollywood Melodrama and Guru Dutt(Seagull Publications).Beyond the Chameleon’s Skill (first book of poems) (Poetrywalla Pub).A Fuss About Queens and Other Stories (Om Books).

More by Darius Cooper in The Beacon:

This is a wonderful piece, Darius. For the substance and the style. For one, it faithfully traces how you grew up with the languages around you. And second, for the same reason as first though I put it differently – because you start with the experience of a child and not a policy or some other airy fairy abstraction. We Indians rarely do that and begin quarreling in a hurry, as if there was something to settle for all of us. There isn’t except the little matter of relating to the reality around us as we grow into adulthood and old age. To the best of our abilities of course!