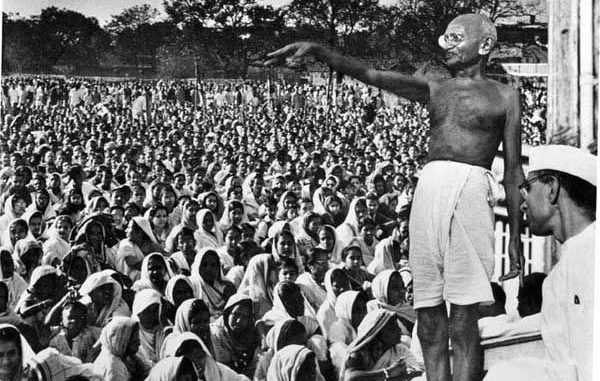

Source: Pinterest

Prelude

Published fifty years after the launch of the non-cooperation movement in 1921, Dharampal’s “Civil Disobedience in India” which forms Volume 2 of his collected writings and from which extracts are reproduced below was a pioneering examination of the antecedents of that movement. At first glance, and in view of the popular conception of its origin, it might seem Dharampal’s investigation of its origins would lead to Europe or America. To Thoreau, William Lloyd Garrison, Tolstoy.

Dharampal treads a different path through time to our own past that he will find isn’t yet past. Stray anecdotes by Gandhi provide him with clues and he journeys to the early years of British colonialism, to a protest by the ‘native’ population against taxes by the Company that began in Banaras and spread to other towns as far away as Bhagalpur and Patna. Between 1810 -11, the Company came face to face with a passive resistance that Dharampal meticulously chronicles by referencing official records, of Collectors and District Magistrates, civil servants of the Raj, on the ground, confronting a strange phenomenon of non-violent boycott and resistance.. The extracts below give a flavor of the movement so vividly as to collapse time, echoing those words from Faulkner’s Absalom! Absalom! that the past isn’t past it isn’t dead yet.

But remarkable too is Dharampal’s scholarship. Born in Uttar Pradesh in 1922, around the time the non-cooperation movement was getting off the ground, Dharampal joined the Quit India movement in the 1940s abandoning halfway his pursuit of a BSc in Physics worked with other nationalist leaders such as Sucheta Kripalani. Dharampal’s work wasn’t over. He had imbibed Gandhi;s world views far too deeply to call it a day. He would go on to undertake studies in what can only be called the recovery of traditions of science, education, self-rule and, civil disobedience suppressed by colonialism, by what Nandy has called the ‘imperialism of categories’ that manufactured the image of Indians as servile, cowardly, superstitious and unfit to self-govern let alone think for themselves and, most important, turned into an article of faith the notion that all progressive ideas had to have come from the West, even of passive resistance to injustice.

Reading these extracts from a chapter of that early colonial period when cognitive imperialism had not yet set almost makes you want to suspend disbelief. Dharampal is writing this fifty years after the the launch of the Non-Cooperation movement and his present, as measured in chronological time, is our past. We read the text written fifty years ago about an event that took place more than two centuries ago. And yet it all seems as vivid as the Punjab farmers’ protests are; as the State’s responses are. Historical time hides the realization that remembrance is also recovery of the self’s multiple legacies as truth, not absolute, perhaps not even coherent truth but angular and certainly resonant. The Beacon

****

Dharampal

INTRODUCTION

TRADITIONALLY what has been the attitude of the Indian people, collectively as well as individually, towards state power or political authority? The prevalent view seems to be that, with some rare exceptions, the people of India have been docile, inert and submissive in the extreme. It is implied that they look up to their governments as children do towards their parents. Text books on Indian history abound with such views.

The past half century or so, however, does not substantiate this image of docility and submissiveness. Many, in fact, regret the supposed transformation. But all, whether they deplore or welcome it, attribute it to the spread of European ideas of disaffection, and most of all to the role of Mahatma Gandhi in the public life of India. According to them, the people of India would have remained inert, docile and submissive if they somehow could have been protected from the European infection and from Mahatma Gandhi.

The twentieth century Indian people’s protest against governmental injustice, callousness and tyranny (actual or supposed) has expressed itself in two forms: one with the aid of some arms, the other unarmed. The protest and resistance with arms has by and large been limited to a few individuals or very small groups of a highly disciplined cadre. Aurobindo, Savarkar, Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekhar Azad (to name a few), in their time have been the spectacular symbols of such armed protest. Unarmed protest and resistance is better known under the names of non-cooperation, civil disobedience and satyagraha. This latter mode of protest owes its twentieth century origin, organisation and practice to Mahatma Gandhi.

In the main, there are two views about the origins of noncooperation and civil disobedience initiated by Gandhiji firstly in South Africa and later in India. According to one group of scholars, Gandhiji learnt them from Thoreau, Tolstoy, Ruskin, etc. According to the other, non-cooperation and civil disobedience were Gandhiji’s own unique discovery, born out of his own creative genius and heightened spirituality.

The statements about the European or American origin of Mahatma Gandhi’s civil disobedience are many. According to one authority on Thoreau, Thoreau’s ‘essay, Resistance to Civil Government, a sharp statement of the duty of resistance to governmental authority when it is unjustly exercised, has become the foundation of the Indian civil disobedience movement.’1 According to a recent writer, ‘Gandhi got noncooperation from Thoreau, and he agreed with Ruskin on cooperation.’2 According to yet another writer, ‘Gandhi agreed with Seeley only in order to apply the lesson learned from Thoreau, William Lloyd Garrison and Tolstoy. The lesson was that the withdrawal of Indian support from the British would bring on the collapse of their rule.’3

The protagonists of the second view are equally large in number, the more scholarly amongst them linking Gandhiji’s inspiration to Prahalada or other figures of antiquity. According to R.R. Diwakar, taking his inspiration from Prahalada, Socrates, etc., Gandhiji adapted ‘a nebulous, semi-religious doctrine to the solution of the problems of day-to-day life and thus gave to humanity a new weapon to fight evil and injustice non-violently.’ Taking note of the traditional Indian practices of dharna, hartal and dasatyaga (leaving the land with all one’s belongings), Diwakar comes to the conclusion that ‘their chief concern was the extra-mundane life and that too of the individual, not of the group or community’, and states ‘there are no recorded instances in Indian history of long-drawn strikes of the nature of the modern “general strike”.’4 According to an analyst of Mahatma Gandhi’s political philosophy, ‘the Gandhian method of non-violent resistance was novel in the history of mass actions waged to resist encroachments upon human freedom.’5 According to another recent student of Mahatma Gandhi, Gandhian non-cooperation and civil disobedience ‘was a natural growth and flowering of a practical philosophy implicit in his social milieu.’6

These two views are integrated in a recent introduction to Thoreau’s essay, On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, referred to above. The writer of this introduction states: ‘Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience marked a significant transition in the development of non-violent action. Before Thoreau, civil disobedience was largely practised by individuals and groups who desired simply to remain true to their beliefs in an evil world. There was little or no thought given to civil disobedience for producing social and political change. Sixty years later, with Mahatma Gandhi, civil disobedience became, in addition to this, a means of mass action for political ends. Reluctantly, and unrecognised at the time, Thoreau helped make the transition between these two approaches.’7

Other writers, like Kaka Kalelkar8 and R. Payne9 though visualising some link which Gandhiji’s non-cooperation and civil disobedience had with India’s antiquity, nevertheless feel, as Kalelkar does, that it was ‘a unique contribution of Mahatma Gandhi to the world community.’ Kalelkar, however, does visualise the possibility that the practices of traga (Kaka Kalelkar incidentally appears to be the only modern writer aware of the practice of traga.), dharna, and baharvatiya, prevailing in Gandhiji’s home area, Saurashtra, may have ‘influenced the Mahatma’s mind.’10

Recent works on ancient Indian polity, and the rights and duties of kings or other political authorities also seem to be in some conflict with the prevalent view of the traditional submissiveness of the Indian people. According to some, the very word ‘Raja’ meant ‘one who pleases’ and therefore any right of the king was subject to the fulfillment of duties and was forfeited if such duties were not performed. Further, an oft quoted verse of the Mahabharata states:

‘The people should gird themselves up and kill a cruel king who does not protect his subjects, who extracts taxes and simply robs them of their wealth, who gives no lead. Such a king is Kali (evil and strife) incarnate. The king who after declaring, ‘I shall protect you’, does not protect his subjects should be killed (by the people) after forming a confederacy, like a dog that is afflicted with madness.’11

Whatever may have been the ruler-ruled relationship in ancient times or the few centuries of Turk or Mughal dominance, in the late seventeenth and eighteenth century, according to James Mill, ‘in the ordinary state of things in India, the princes stood in awe of their subjects.’12 Further, according to Gandhiji, that ‘we should obey laws whether good or bad is a new fangled notion. There was no such thing in former days. The people disregarded those laws they did not like.’13 Elaborating on the idea of passive resistance, Gandhiji stated:

The fact is that, in India, the nation at large has generally used passive resistance in all departments of life. We cease to cooperate with our rulers when they displease us. This is passive resistance.14

Giving a personally known instance of such noncooperation, he added:

In a small principality, the villagers were offended by some command issued by the prince. The former immediately began vacating the village. (It is possible that such recourse to the vacating of villages, towns, etc., as noted by Gandhiji and as threatened in 1810-11 at Murshedabad etc., was of a much later origin than the various other forms of non-cooperation and civil disobedience described in this volume. Resort to such an extreme step as the vacating of villages etc., indicates increasing alienation of the rulers from the ruled and further a substantial weakening of the strength of the latter. Such a situation is in glaring contrast to the situation where ‘the princes stood in awe of their subjects’.

Though such an extreme step at times may have still worked in relation to Indian rulers who were not yet completely alienated from the ruled in Gandhiji’s young days, its potential use against completely alien rulers, such as the British, must have become very small indeed.) The prince became nervous apologised to his subjects and withdrew his command. Many such instances can be found in India.15

It is not necessary to add that Gandhiji’s discovery of civil disobedience is not just a borrowing from his own tradition. In a way it came out of his own being. His knowledge of its advocacy or limited practice in Europe and America may have provided him further confirmation. But it is the preceding Indian historical tradition of non-cooperation and civil disobedience which made possible the application of them on the vast scale that happened under his leadership.

It appears that Mahatma Gandhi as well as Mill had a more correct idea of the ruler-ruled relationship in India than conventional historians. Even without going far back into Indian history, a systematic search of Indian and British source materials pertaining to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries should provide ample evidence of the correctness of Mahatma Gandhi’s and Mill’s view. Further, it would probably also indicate that civil disobedience and non-cooperation were traditionally the key methods used by the Indian people against oppressive and unjust actions of government.

Even with a relatively cursory search, a number of instances of civil disobedience and non-cooperation readily emerge. These are recorded primarily in the correspondence maintained within the British ruling apparatus. For example, the Proceedings of the British Governor and Council at Madras, dated November, 1680 record the following response by ‘the disaffected persons’ in the town of Madraspatnam to what they considered arbitrary actions on the part of the British rulers:

The painters and others gathered at St.Thoma having sent several letters to the several casts of Gentues in town, and to several in the Company’s service as dubasses, cherucons or chief peons, merchants, washers and others and threatened several to murther them if they came not out to them, now they stopt goods and provisions coming to town throwing the cloth off of the oxen and laying the dury, and in all the towns about us hired by Pedda Yenkatadry, etc: the drum has beaten forbidding all people to carry any provisions or wood to Chenapatnam alias Madraspatnam and the men’s houses that burnt chunam for us are tyed up and they forbid to burn any more, or to gather more shells for that purpose.16

This tussle lasted for quite some time. The British recruited the additional force of the ‘Black Portuguese’, played the less protesting groups against the more vehement, arrested the wives and children of those engaged in the protest, and threatened one hundred of the more prominent amongst the protestors with dire punishment. Finally, the incident seems to have ended in some compromise.

At a much later period, reporting on a peasant movement in Canara in 1830-31, the district assistant collector wrote:

Things are here getting worse. The people were quiet till within a few days, but the assemblies have been daily increasing in number. Nearly 11,000 persons met yesterday at Yenoor. About an hour ago 300 ryots came here, entered the tahsildar’s cutcherry, and avowed their determination not to give a single pice, and that they would be contented with nothing but a total remission. The ahsildar told them that the jummabundy was light and their crops good. They said they complained of neither of these, but of the Government generally; that they were oppressed by the court, stamp regulation, salt and tobacco monopolies, and that they must be taken off.17

Referring to the instructions which he gave to the tahsildar, the assistant collector added:

I have also told him, to issue instructions to all persons, to prevent by all means in their power the assemblies which are taking place daily, and if possible to intercept the inflammatory letters which are at present being despatched to the different talooks.18

He further stated:

The ryots say that they cannot all be ‘punished’, and the conspirators have as it were excommunicated one Mogany, who commenced paying their Kists. The ferment has got as far as Baroor and will soon reach Cundapoor. As the dissatisfaction seems to be against the Government generally and not against the heaviness of the jummabundy, speedy measures should, I think be taken to quench the flame at once. But in this district not a cooley can be procured. The tahsildar arrived here yesterday with the greatest difficulty.19

These protests were at times tinged by violence at some point. Most often, however, what is termed as violence was the resort to traga, koor, etc., (which are familiar under other names) inflicted by individuals upon themselves as a means of protest.

On the occasions when the people actually resorted to violence, it was mostly a reaction to governmental terror, as in the cases of the various ‘Bunds’ in Maharashtra during the 1820-40s. 20 (At what point the people reacted to terror and repression by resorting to violence is a subject for separate study.)

(The violence manifest in modern movements of civil disobedience and the counter violence adopted by the authorities to deal with it require deeper investigation. According to Charles Tilly in Collective Violence in European Perspective: ‘A large proportion of the…disturbances we have been surveying turned violent at exactly the moment when the authorities intervened to stop an illegal but non-violent action…the great bulk of the killing and wounding…was done by troops or police rather than by insurgents or demonstrators.’ Commenting on this, Michael

Walzer believes that ‘the case is the same…in the United States.’ (Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War, and Citizenship, 1970. p. 32))

Overall, the civil disobedience campaigns against the new British rulers, including the one documented in this volume, did not succeed. The reasons for this must be manifold. Partly, the effectiveness of such protests was dependent upon there being a commonality of values between the rulers and the ruled. With the replacement of the indigenous rulers by the British (whether de jure or de facto is hardly material) such commonality of values disappeared. The British rulers of the eighteenth and nineteenth century did not at all share the same moral and psychological world as their subjects. Over time, what James Mill termed the ‘general practice’ of ‘insurrection against oppression’21 which had prevailed up to the period of British rule, was gradually replaced by ‘unconditional submission to public authority.’ In the early 1900s, it seemed to Gopal Krishna Gokhale ‘as though the people existed simply to obey.’22

[…]

II

[…]

In 1810, on the instructions of the directing authorities in England, the Government of Bengal (Fort William) decided to levy a new series of taxes in the provinces of Bengal, Behar, Orissa, Benares and the Ceded and Conquered territories (these latter now constitute part of Uttar Pradesh). One of these, recommended by its Committee of Finance, was a tax on houses and shops. This tax was enacted on October 6, 1810 by Regulation XV, 1810. According to its preamble, the Regulation was enacted ‘with a view to the improvement of the public resources’ and to extend ‘to the several cities and principal towns in the provinces of Bengal, Behar, Orissa and Benares, the tax which for a considerable period, has been levied on houses, situated within the town of Calcutta.’ The Regulation provided for a levy of ‘five per cent on the annual rent’ on all dwelling houses (except the exempted categories) built of whatever material, and a levy of ’10 per cent on the annual rent’ on all shops. Where the houses or shops were not rented but occupied by the proprietors themselves, the tax to be levied was to be determined ‘from a consideration of the rent actually paid for other houses (and shops) of the same size and description in the neighbourhood.’

The exempted categories included ‘houses, bungalows, or other buildings’ occupied by military personnel; houses and buildings admitted to be ‘religious edifices’; and any houses or shops which were altogether unoccupied. The tax was to be collected every three months and it was laid down that when it remained unpaid ‘the personal effects of the occupant shall in the first instance be alone liable to be sold for the recovery of the arrear of tax.’ Further, if some arrear still remained ‘the residue shall be recovered by the distress and sale of the goods, and chattels of the proprietor.’ Though appeals were admissible against unjust levy, etc., ‘to discourage litigious appeals, the judges’ were ‘authorised to impose a fine’, the amount depending on the circumstances, etc., of the applicant, on all those whose appeals ‘may prove on investigation to be evidently groundless and litigious’.

The collector of the district was ‘allowed a commission of five per cent’ on the net receipts. Incidentally, such a commission accorded to the collectors was not unusual at this time. The collectors received similar commissions on net collections of land revenue.

The total additional revenue estimated to arise from this tax was rupees three lakhs in a full year. Comparatively speaking, this was not very large. Of the total expected receipts from the various new or additional levies enacted around this time, the house tax was to contribute around ten per cent. In relation to the total tax revenue of the Bengal Presidency for 1810-11 (Rs.10.68 crores), most of it derived from the rural areas, the house tax amount was insignificant. But taken along with the other levies imposed about this time, large portions of which fell on the urban areas, this tax became a rallying point for widespread protest.

[…]

EVENTS AT BENARES

The protest begins at Benares. As Benares was then the largest city in northern India and possibly the best preserved in terms of traditional organisation and functioning, this was most natural. Also it may have been due to the Benares governmental authorities being more prompt in taking steps towards enforcing the house tax.

The following were the main arguments against the levy of the tax, as they emerge from the documented correspondence, and from the petition of the inhabitants of Benares (rejected by the court of appeal and circuit, partly because its ‘style and contents’ were ‘disrespectful’)23:

(i) Former sooltauns never extended the rights of Government (commonly called malgoozaree) to the habitations of their subjects acquired by them by descent or transfer. It is on this account that in selling estates the habitations of the proprietors are excepted from the sales.

Therefore the operation of this tax infringes upon the rights of the whole community, which is contrary to the first principles of justice.

(ii) It is clear that the house tax was enacted only for the purpose of defraying the expenses of the police. In the provinces of Bengal and Behar, the police expenses are defrayed out of the stamp and other duties, and in Benares the police expenses are defrayed from the land revenue (malgoozaree). Then on what grounds is this tax instituted?

(iii) If the Shastra be consulted it will be found that Benares to within five coss round is a place of worship and

by Regulation XV 1810 places of worship are exempted from the tax.

(iv) There are supposed to be in Benares about 50,000 houses, near three parts of which are composed of places of worship of Hindoos and Mussulman and other sects an houses given in charity by Mussulman and Hindoos. The tax on the rest of the houses will little more than cover the expenses of the Phatuckbundee. Then the institution of a tax which is calculated to vex and distress a number of people is not proper or consistent with the benevolence of Government.

(v) There are many householders who are not able to repair or rebuild their houses when they fall to ruin and many who with difficulty subsist on the rent derived therefrom,how is it possible for such people to pay the tax?

(vi) Instead of the welfare and happiness of your poor petitioners having been promoted, we have sustained repeated injuries, in being debarred from all advantages and means of profit and in being subject to excessive imposts which have progressively increased

(vii) It is difficult to find means of subsistence and the stamp duties, court fees, transit and town duties which have increased tenfold, afflict and affect everyone rich and poor and this tax like salt scattered on a wound, is a cause of pain and depression to everyone both Hindoo and Mussulman; let it be taken into consideration that as a consequence of these imposts the price of provisions has within these ten years increased sixteenfold. In such case how is it possible for us who have no means of earning a livelihood to subsist?

The authorities of Benares appear to have been the first in implementing the house tax regulation. Possibly, this promptness resulted from their being better organised with regard to civil establishment as well as military support.

Whatever the reasons for their speedy compliance within a mere seven weeks after the passing of the regulation the collector of Benares, as the authority responsible for levying and collecting the house tax, started to take detailed steps towards the regulation’s enforcement. On November 26, he informed the acting magistrate of the steps he was taking to determine the assessment on each house and requested him to place copies of the regulation in the several thanas for general information.

He further requested the magistrate for police support for his assessors when they began their work in the mohallas.

On December 6, the collector gave further details to the magistrate and requested speedy assistance from the thannadars etc. The acting magistrate replying to the collector on December 11, informed him of the instructions he had issued but stated that for the time being he did not feel that the police should accompany the assessors. He, however, assured the collector that ‘should any obstacle or impediment on the part of the house-holders be opposed to your officers in the legal execution of their duties, I shall, of course, upon intimation from you, issue specific instructions to the officers of police to enforce acquiescence.’ (pp.59-60) (Page numbers here, and on the following pages, refer to the page numbers of documents reproduced later in this volume.)

The assessment having started, and meeting with instant opposition, the acting magistrate thus wrote to the Government at Calcutta on December 25:

‘I should not be justified in withholding from the knowledge of the Right Hon’ble the Governor-General-in-Council, that a very serious situation has been excited among all ranks and descriptions of the inhabitants of the city by the promulgation of Regulation XV, 1810. (p.60)

After giving the background he added:

‘The people are extremely clamorous; they have shut up their shops, abandoned their usual occupations, and assembled in multitudes with a view to extorting from me an immediate compliance with their demands, and to prevail with me to direct the collector to withdraw the assessors until I receive the orders of Government. With this demand I have not thought proper to comply. I have signified to the people that their petitions shall be transmitted to the Government but that until the orders of Government arrive, the Regulation must continue in force, and that I shall oppose every combination to resist it. By conceding to the general clamour I should only have encouraged expectation which must be eventually disappointed, and have multiplied the difficulties which the introduction of the tax has already to contend with. (p.61)

Three days later, on the 28th, he sent another report:

‘The tumultuous mobs which were collected in various places between the city and Secrole, on the evening of the 20th instant, and which dispersed on the first appearance of preparations among the troops, did not reassemble on the morning of the 26th and I was induced to hope that the people in general were disposed to return to order and obedience.

‘But in the afternoon the agitation was revived: an oath was administered throughout the city both among the Hindoos and the Mahommedans, enjoining all classes to neglect their respective occupations until I should consent to direct the collector to remove the assessors and give a positive assurance that the tax should be abolished. It was expected that the outcry and distress occasioned by this general conspiracy would extort from me the concession they required. The Lohars, the Mistrees, the Hujams, the Durzees, the Kahars, Bearers, every class of workmen engaged unanimously in this conspiracy and it was carried to such an extent, that during the 26th the dead bodies were actually cast neglected into the Ganges, because the proper people could not be prevailed upon to administer the customary rites.

These several classes of people, attended by multitude of others of all ranks and descriptions, have collected together at a place in the vicinity of the city, from whence they declare nothing but force shall remove them unless I consent to yield the point for which they are contending’.(p.62)

On December 31, the acting magistrate further reported:

‘Several thousands of people continue day and night collected at a particular spot in the vicinity of the city, where, divided according to their respective classes, they inflict penalties upon those who hesitate to join in the combination. Such appears to be the general repugnance to the operation of the Regulation, that the slightest disposition evinced by any individual to withdraw from the conspiracy, is marked not only by general opprobrium but even ejectment from his caste.’ (p.64)

[…]

Meanwhile, the humbling process, initiated through the Rajah of Benares and the other ‘loyal’ and ‘faithful public servants’ went further. On February 7, the acting magistrate forwarded to the Government a petition, presented to him by the Rajah of Benares in the name of its inhabitants. This he described as an ‘ultimate appeal’ by means of which the petitioners, in the words of the petition, ‘present themselves at last before His Lordship-in-Council’ and ‘humbly’ represented that disobedience ‘was never within our imagination.’ Instead, they added, ‘in implicit obedience’ to the proclamation of the magistrate of January 13 ‘as to the decree of fate, we got up, and returned to our homes, in full dependence upon the indulgence of the Government.’

The Government however still did not ‘think proper to comply with the application of the inhabitants’ to a ‘greater extent than will be done’ by the operation of its orders of January 11. This order of Government, along with the information of the earlier modifications, was conveyed a week later, on February 23, to the Rajah and principal inhabitants of Benares by the magistrate, who in his proclamation to the inhabitants of Benares, of the same date, concluded with the view, ‘that no ground now remains for the complaint or discontent.’

The people in general, notwithstanding their having submitted to the orders of Government ‘as to the decree of fate’ as stated in their petition submitted through the Rajah of Benares, did not share the magistrate’s view and exhortation.

Nearly a year later, on December 28, 1811, the collector reported:

At an early period I directed my native officers to tender to all the householders or tenants whose houses had already been assessed, a note purporting the computed rate of rent of each house, and the rate of tax fixed; and I issued at the same time a proclamation directing all persons who had objections of any nature to offer to the rates of rent or tax mentioned in such note to attend and make known the same that every necessary enquiry might be made and all consistent redress afforded. In the above mentioned proclamation, I fixed a day in the week for specially hearing such cases and repaired to the city for that purpose. Neither would any householders or tenants receive such note nor did any one attend to present petition or offer objection

The most in sullen silence permitted the assessors to proceed as they pleased rigidly observing the rule to give no information or to answer any questions respecting the tax; in determination that they would not in anywise be consenting to the measure, that the assessors might assess and the executive officers of the tax might realise by distraint of personal or real property; they could not resist but they would not concur.’ (pp.99-100)

But, as a consolation for the authorities the collector added:

‘A few exceptions were found in some of the principal inhabitants of the city either in the immediate employ of Government or in some degree connected with the concerns of Government or otherwise individually interested in manifesting their obedience and loyalty. These persons waited on me and delivered in a statement of their houses and premises and the actual or computed rent of the same and acknowledged the assessment of tax.’(p.100).

Yet such exceptions did not seem to console much and in concluding his report, the collector ‘strenuously’ urged ‘as an indispensable measure of precaution, that no collection be attempted without the presence of a much larger military force than is now at the station. (p.101)

Such withholding of concurrence and cooperation was apparent even earlier in February. While forwarding the ‘ultimate appeal’ of the inhabitants, the acting magistrate had stated:

‘I believe the objection which they entertain against the measure in question, is pointed exclusively at the nature and principle of the tax, and not in the least at the rate of assessment by which it will be realised. The inhabitants of this city appear to consider it as an innovation, which, according to the laws and usages of the country, they imagine no government has the right to introduce; and that unless they protest against it, the tax will speedily be increased, and the principle of it extended so as to affect everything which they will call their own. Under the circumstances, I fear, they will not easily reconcile themselves to the measure.’ (p.93)

[…]

EVENTS IN PATNA

Now to turn to the other towns. As stated by the Benares collector in his letter of January 2, the inhabitants of these other towns seemed to have been watching the events at Benares. On January 2, the magistrate of Patna forwarded 12 petitions regarding the house tax from the city’s inhabitants, the Government informing him on the 8th of their rejection, but cautioning the magistrate to use ‘gentle and conciliatory means’ in stopping the inhabitants from convening meetings or petitioning ‘while the discussion is depending at Benares.’ It however instructed him to use the various means he possessed under his general powers and instructed him to report without delay to Government any ‘tumultuary meetings’ or ‘illegal cabals.’

[…]

![]()

Dharampal: 1922-2006

III

This story of the 1810-11 protest in Benares and other towns, as it emerges in more vivid detail from the documents, seems not really very different from what has happened during the noncooperation and civil disobedience movements of the 1920s and 1930s in different parts of India. It may, however, be worthwhile here to recapture the main elements of the 1810-11 happenings at Benares and other places.

The immediate cause of the protest was the levy of the house tax. Yet unhappiness and revulsion had been simmering for a considerable time previous to this levy. By 1810, these areas had been under British domination for about 50 years and the people in general (whether at Benares, Bhagalpur or Murshedabad) had begun to be apprehensive of the doings of Government. As stated by the people of Benares, the levy of the house tax felt ‘like salt scattered on a wound.’ The people of Murshedabad felt it like ‘a new oppression’ and stated that it had ‘in truth struck us like a destructive blast.’

The main elements behind the organisation of civil disobedience at Benares were:

- Closing of all shops and activity to the extent that even ‘the dead bodies were actually cast neglected into the Ganges, because the proper people could not be prevailed upon to administer the customary rites.’ (p.62)

- Continuous assemblage of people in thousands (one estimate24 puts the number at more than 200,000 for many days) sitting in dhurna, ‘declaring that they will not separate till the tax shall be abolished.’ (p.71)

- The close links made by the various artisans and craftsmen with the protest through their craft guilds and associations.

- The Lohars, at that time a strong and well-knit group, taking the lead, calling upon other Lohars in different areas to join them. (p.71)

- A total close-down by the Mullahs (boatmen). (p.70)

- The assembled peopled who ‘bound themselves by oath never to disperse’ till they had achieved their object. (p.69)

- The dispatch of emissaries ‘to convey a Dhurm Puttree to every village in the province, summoning one individual of each family to repair to the assembly at Benares.’ (p.69)

- ‘Individuals of every class contributed each in proportion to his means to enable them to persevere’, and ‘for the support of those, whose families depended for subsistence on their daily labour.’ (p.69)

- ‘The religious orders’ exerting all their influence to keep the people ‘unanimous.’ (p.69)

- ‘The combination was so general, that’, according to the magistrate ‘the police were scarcely able to protect the few who had courage to secede, from being plundered and insulted.’(p.69)

- The displaying of protesting posters about the streets of Benares. The magistrate called them ‘inflammatory papers of the most objectionable tendency’ and ‘offered a reward of Rs.500 for every man on whom such a paper may be found.’ (p.85)

Regarding the people’s own view of the unarmed resistance they had put up, the collector reported: ‘Open violence does not seem their aim, they seem rather to vaunt their security in being unarmed in that a military force would not use deadly weapons against such inoffensive foes. And in this confidence they collect and increase, knowing that the civil power cannot disperse them, and thinking that the military will not.’ (p.71) The taking of such steps seems to have come to them naturally. Further, their protesting in this manner in itself did not imply any enmity between them and state power. It is in this context that the rejected petition quoted some prevalent saying: ‘to whom can appeal for redress of what I have sustained from you, to whom but to you who have inflicted it.’ The concept of ruler-ruled relationship which they seem to have held, and which till then had perhaps been widely accepted, was of continuing interaction between the two. Such a dialogue seems to have been resorted to whenever required, and its instrumentalities included all that the people of Benares employed in this particular protest

[…]

The happenings at Patna, Saran, Murshedabad (though seemingly of lesser intensity) and at Bhagalpur appear to be of the same nature and similarly conducted as at Benares. Even at Bhagalpur, where the collector, seemingly forgetting where he was, began to mete out summary justice in the manner of contemporary British justices of the peace, the people, though enraged, remained peaceful. They continued assembling in thousands, totally unarmed and even the ‘women, and their children seemed to have no dread of the consequences of firing among them, but rather sought it.’

If the dates, (1810-12) were just advanced by some 110 to 120 years, the name of the tax altered and a few other verbal changes made, this narrative could be taken as a fair recital of most events in the still remembered civil disobedience campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s. The way the people organised themselves, the measures they adopted, the steps they took to sustain their unity and the underlying logic in their minds from which all else flowed are essentially similar in the two periods. (It is by no means implied here that there are no differences at all between the non-cooperation and civil disobedience in 1810-11 and what is termed as “Satyagraha”. To an extent the concept of satyagraha, since this term was coined by Mahatma Gandhi has become more and more involved. For many, it cannot be resorted to be by any who have not been trained to an ashram life etc. But ordinarily satyagraha can only mean non-cooperation and civil disobedience of the type resorted to in Benares in 1810-11. And when Gandhiji recommended to the Czechs and the Poles to resort to satyagraha, it could only have been this Benares type of protest (suitably modified according to their talents) which he had in mind)

There is one major difference, however. While the people in 1810-11 could still act and move on their own, the people of India a century later could not. The century which intervened between the two (or a larger or shorter period for some other areas) wholly sapped their courage and confidence and, at least on the surface, made them docile, inert and submissive in the extreme. It is this condition which Gandhiji overcame to put the people back on the path of courage and confidence.

[…]

IV

The story of the 1810-11 protests at Benares and other towns does not necessarily include every form of protest resorted to by the Indian people in relation to governmental or other authority.

A more systematic exploring of eighteenth and early nineteenth century primary records (as well as records of still earlier periods—if such exist) may well disclose several other forms of protest and their principal features. Yet it should establish beyond any doubt that the resort to non-cooperation and civil disobedience against injustice etc., are in the tradition of India. It also confirms Gandhiji’s observation that ‘in India the nation at large has generally used passive resistance in all departments of life. We cease to cooperate with our rulers when they displease us.’

It further suggests that either intuitively or through knowledge of specific instances, Mahatma Gandhi was very much aware of such a tradition.

Does the knowledge that non-cooperation and civil disobedience are in the tradition of India have any relevance to present day India? It appears to the present writer that there is such a relevance both for the people as well as governments and other authorities. A realisation of it in fact seems crucial in the sphere of people-government relationship, and its acceptance imperative for the health and smooth functioning of Indian polity even today.

[…]

*********

Notes For purposes of brevity the works cited have been omitted. Readers are encourages to read them in the original text: Civil Disobedience in Indian Tradition. Volume II. Other India Press. Mapusa, Goa India.

Dharampal: Collected Writings (All Other India Press publications} Volume I: Indian Science and Technology in the 18th Century Volume II: Civil Disobedience in Indian Tradition Volume III: The Beautiful Tree: Indian education in the Eighteenth Century Volume IV: Panchayat Raj And Indian Polity Volume V: Essays on Tradition, Recovery and Freedom For a full list of his writings see: https://www.dharampal.net/ Image of Dharampal from : https://www.dharampal.net/

Leave a Reply