Vinay Lal

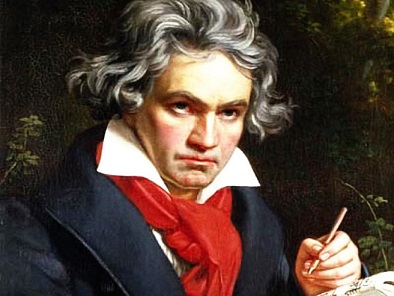

LUDWIG van Beethoven was born 250 years ago in December 2020 and the German-speaking world would, in ordinary circumstances, have been ablaze with celebrations to honour the memory of the composer of whom the Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi, himself a man of no mean reputation, reportedly said: ‘Before the name of Beethoven, we must all bow in reverence.’ We are living at a time of ‘lists’, and there are now even lists of lists; and in all such lists featuring the ‘greatest composers’, Beethoven features at the very top, edged out only by Johann Sebastian Bach and sometimes, rather surprisingly, the Russian composer Ivor Stravinsky. Bach is the musician’s musician; but, I suspect if popular choice be taken into consideration, Beethoven would easily be the crowd favorite.

The coronavirus pandemic has of course muted most celebrations in Germany, Austria, and elsewhere in Europe, but it is safe to say that, even without the pandemic, there would not have been much of a stir in India. Beethoven’s name is by no means unknown, at least not among the more Anglicized middle-class populations of the metros, and India doubtless has its share of afficionados of Western classical music. Fifty years ago, the Indian government even issued a postage stamp in his honour, and they followed it up with a stamp in 1985 in joint tribute to George Frideric Handel and Bach, both born in 1685. A few years later there appeared a postage stamp in honour of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It is something of a remarkable tribute to the ecumenism of the Indian sensibility that, even though Western classical music commanded a miniscule audience in India, the government at that time thought it fit to acknowledge the great composers as representatives of ‘world culture’. Among Indian figures, only Gandhi has similarly been honoured in the philatelic traditions of the West. These gestures may be taken as inconsequential by those who have little understanding of the excitement that philately generated for decades around the world before email, the advent of other forms of communication technology, and the precipitous decline in the epistolary art all contributed to rendering philately nearly obsolete. It is quite likely, for instance, that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was at work on his stamp collection one day in December 1941 when he was taken aside to be informed that the Japanese had launched an attack on Pearl Harbor.1

Yet what is true of India with regards to its miniscule constituency for Western classical music is scarcely the case in China, Japan, and Korea. It is an unimpeachable fact that in these countries Western classical music has over the decades gained enormous ground. Why that should be the case is itself a matter of considerable discussion. Some have speculated that China’s one-child policy, and the low birth rate through much of East Asia, encouraged parents to invest heavily in their children; and others, elaborating on this point, have noted that the Confucian ideal of education is attentive to the cultivation of the arts. Many of the greatest practitioners these days of such music are East Asian, from countries in what is sometimes called the ‘Confucian zone’, and they are increasingly dominating orchestra halls and performing centers in the US and Europe. Around 2005, 36 million Chinese students were estimated to be taking classes in piano, in comparison with around six million in the US—and of the six million in the US, it would be worthwhile knowing how many are of East Asian origin.2 A few years ago the German violinist Viktoria Elisabeth Kaunzner wrote that a ‘performance by the Seoul Philharmonic conducted by Eliahu Inbal of Shostakovich’s Symphony no.11 prompted the same kind of enthusiasm from the audience that one sees after a goal is scored at the FIFA World Championship’.3 This would be unthinkable in India—even, to be quite clear about it, in Russia, Germany, or elsewhere in Europe or the United States. The Symphony Orchestra of India, based in Mumbai, appears to be nearly the only such organization of its kind in the entire country, and Bombay again seems to be host to the one and only chamber music group in the country. It may be that in princely India such music had perhaps more patronage than it would in independent India: the prodigious Philomena Thumboochetty gave a violin recital at Mysore’s B.R.V. Theatre and ‘was assisted’ by ‘The Mysore Palace Orchestra’.4

Just why India has not furnished a hospitable ground to Western classical music is a question that is not without interest, though a somewhat perceptive student of music might object that the question presumes what in fact needs to be proven. The most general form of the argument would be that the country’s own ‘classical music’ traditions are unfathomably deep, but one might then ask why it is that Italian, Continental, and Mexican cuisines among many others have now been absorbed into the repertoire of Indian chefs when India’s own culinary traditions are similarly extraordinarily complex but that the same story does not hold true for music. Some ethnomusicologists have written about the manner in which the violin, introduced to India two hundred years ago, has now become intrinsic to Carnatic musical tradition. But the history of violin’s absorption in this fashion is singular; no other Western instrument can lay claim to such a history in India. A more interesting argument might be made apropos of Hindi film music. On the one hand, Hindi film music’s monopoly on Indian musical tastes is seen as nearly total, at least in north and central India; at the same time, the orchestral music of many Hindi films shows the lasting influence of Western classical music, one which may not be apparent to everyone—though perhaps a hint may be found in the fact that hundreds of Hindi movies, from Andaz (1949) to Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995) and beyond, featured the actor ostensibly playing the piano.

We need not be detained much further by considerations of why Western classical music, even say the pleasant-sounding music of Vivaldi or Mozart in contrast to the demanding music of Shostakovich, Arnold Schoenberg, or Olivier Messiaen, has not able to take root in the fecund soil of India, though this is a question that merits further investigation. It may be that Yehudi Menuhin, one of the very few Western classical music performers of immense stature to have developed a real attachment for India, had some insights into this matter and perhaps his papers will shed further light on this matter. He visited India for the first time in 1952, the first of many visits, on the invitation of Jawaharlal Nehru and played a number of concerts on his two-month visit, with the proceeds from his concerts in Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, and Bangalore going to the Prime Minister’ Relief Fund, primarily to alleviate food shortages in Madras.5 The concerts were held—where else, this being India—in cinema halls: the New Empire in Calcutta, and the Regal and Excelsior in Bombay. Among the pieces played, recalled Zubin Mehta—whose father, Mehli Mehta, was the concertmaster—in his autobiography, was Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Yehudi Menuhin’s autobiography speaks to his abiding interest in yoga and the manner in which Indian music entirely took him ‘by surprise’: ‘I knew neither its nature nor its richness, but here, if anywhere, I found vindication of my conviction that India was the original source. The two scales of the West, major and minor, with the harmonic minor as variant, the half-dozen ancient Greek modes, were here submerged under modes and scales of (it seemed) inexhaustible variety.’6

There are yet more surprising ways, as I shall now suggest, to think of the inheritance of Western classical music, and more particularly the music of Beethoven, in relation to India. As is true of so much in our country, the name of Beethoven is also inextricably linked up with the name of someone who is inescapably present in nearly every conversation—Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. This is as unlikely a pairing as any that one might ordinarily think of, except perhaps in the sense that both Gandhi and Beethoven are what may be called ‘world historical figures’. They are, quite simply, ‘giants’—but by this reasoning they could be paired with many other giants, men and women of altogether exceptional stature. The difficulty in bringing the two together, on grounds that would be less flimsy than their extraordinary place in the course of human affairs, is that, at least in the common view, Beethoven was an ‘artist’ who created music that transcends the everyday and the political, while Gandhi was fundamentally immersed in the political life.

However, a view of Beethoven which presumes that instrumental music is a pure art dissociated from politics, and that Beethoven himself was above politics, cannot withstand scrutiny as students of the social, cultural, and political history of music know all too well. Biographers of the great composer unfailingly recount the story of his tortured relationship to the figure of Napoleon.7 Beethoven was a staunch Republican and an ardent defender of liberty and, in common with many Germans of his day, looked to Bonaparte, First Consul of the Empire, as a political genius. The democratic ideals of ancient Greece seemed to be reincarnated in the political aspirations and ideas of the Jacobins of post-revolutionary France. Beethoven had intended to dedicate his Third Symphony to the great liberator; but before the Eroica (‘Heroic’) Symphony, as the piece would later come to be known, had received its inaugural performance, Napoleon declared himself Emperor of France. Enraged by this act of betrayal, Beethoven struck Napoleon’s name from the title page which originally bore the inscription: ‘Sinfonia grande intitolata Bonaparte del Sigr Louis van Beethoven’ (‘Grand Symphony titled Bonaparte by Mr. Ludwig van Beethoven’)8. As he told his pupil Ferdinand Ries, who first brought him the news of Napolean’s installation as Emperor, ‘So he too is nothing more than an ordinary man. Now he will trample on all human rights and indulge only his own ambition. He will place himself above everyone and become a tyrant.’ That the political can be read into his music is nowhere so amply demonstrated than in the uses, explored with marvelous dexterity and admirable scholarship by Esteban Buch, to which Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony has been put by people with all shades of political opinion, from Romantics and idealists to the Nazis and the advocates of apartheid in South Africa and the erstwhile Rhodesia.9

But what of Gandhi, who, among many other things, has been charged by the likes of Nirad Chaudhari and V.S. Naipaul with being wholly indifferent to the arts? It is commonly supposed that his leadership of what we in India call the ‘freedom struggle’, his painstakingly detailed and rigorous commitment to the constructive programme, and his attention to myriad other issues—among them, social reform, the condition of Indian villages, the eradication of Untouchability, the Hindu-Muslim question—left him with no time for poetry, music, painting, and such emerging art forms as cinema. Many of his critics, however, aver that this is a prosaic and rather forgiving view of his shortcomings. They hold that Gandhi was without an aesthetic sensibility and that he had no appetite for art or other things that he took to be rather frivolous. The more astute of his critics, aware of Gandhi’s fondness for hymns such as Narsi Mehta’s “Vaishnavajana To”, think that too much has been made of ‘the music of the charkha.10 Rabindranath Tagore, in the famous exchange that he had with Gandhi in 1921, spoke rather of the ‘cult of the charkha’ while acknowledging the ‘notes of the music of this wonderful awakening of India by love’ that the Mahatma had made possible.11 On the other hand, even as Gandhi is increasingly coming under attack for some of his views on race, caste, and sex, many scholars are moving closer to the view that he was fully engaged with the arts and had a distinct aesthetic sensibility. One might think that the scholar Cynthia Snodgrass’s massive doctoral dissertation, The Sounds of Satyagraha, should put to rest doubts about Gandhi’s fondness for music—but perhaps, as shall be seen, it will not.12

The story of Mirabehn, in this connection, cannot be told often enough. It was Beethoven, of course, who brought the aristocratic Madeleine Slade to Gandhi. She venerated Beethoven and in the mid-1920s paid a visit to Romain Rolland, a celebrated French novelist, dramatist, and essayist, and an eminent scholar of Beethoven. Rolland appeared to her as someone who could perhaps help bring her into the presence of the divine. He advised her that, if she was in the quest of a genius to whom she could offer her adoration and service, she might think of someone living—a skinny Indian known as the ‘Mahatma’. Rolland would have known: though in 1929-30 he would go on to write biographies of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, he had as early as 1924 penned a book on Gandhi describing him as ‘the man who became one with the universal being’.13 That was precisely the language Rolland used to characterize Beethoven, who reigned supreme ‘in the kingdom of the spirit’: what Beethoven had been to the 19th century, Gandhi was to the 20th century. Why yearn for an understanding of greatness through the dead, Rolland seemed to be saying to her, when the greatest man alive in the world can dazzle you with the music of his spindle no less than you are swayed by the violin of your revered composer.

Just how the daughter of an English Rear-Admiral wound up spending most of her adult life as the companion of Mohandas Gandhi for two decades is a story with turns and twists that leaves most good fiction looking impoverished. By the mid-1920s, Gandhi was used to the adoration of the millions; but nevertheless he must have been struck by the letter that she addressed to him, imploring him to accept her as a disciple. Never one to entirely discourage someone who was prepared to embrace a relentless quest for truth and live by the principles of ahimsa, Gandhi wondered whether a woman accustomed to live in the lap of luxury would be able to sleep on a hard floor, forswear meat, wash her own clothes, sweep the ashram floor, and empty her own chamber pot. So he advised her to practice simple living for one year—which she dutifully did, jettisoning her gowns, taking up spinning, replacing roast dinners with a vegetarian diet, and ordering, much to the astonishment of her family, the house staff to remove the bedding from her room. Mirabehn’s autobiography, The Spirit’s Pilgrimage (1960), tells it all but no passage is as priceless as her description of her first meeting with Gandhi when she is ushered into his presence:

‘As I entered [the room], a slight brown figure rose up and came toward me. I was conscious of nothing but a sense of light. I fell on my knees. Hands gently raised me up, and a voice said: ‘You shall be my daughter. . . . Yes, this was Mahatma Gandhi, and I had arrived.’14

Only a decade after Gandhi’s assassination did she depart—heading for the Vienna Woods, where she eked out the remaining twenty years of her life, stalking the trails taken by Beethoven, listening to his Pastoral Symphony (No. 6), and working on The Spirit of Beethoven, left unfinished at her death.15

It is as Mirabehn rather than Madeleine Slade that she visited Rolland again in late 1931—this time as Bapu’s devoted acolyte, constant companion, and personal assistant. Gandhi was on his way back to India from the Round Table Conference and at Rolland’s invitation they stopped to see him in Switzerland. Writing to an American friend shortly after the departure of his distinguished visitors, Rolland noted that Gandhi asked him to play ‘a little of Beethoven’ after dinner: ‘He does not know Beethoven, but he knows that Beethoven has been the intermediary between Mira and me, and consequently between Mira and himself, and that in, in the final count, it is to Beethoven that the gratitude of us all must go.’16 Rolland played him a piano transcription of the andante of the Fifth Symphony and Les Champs Elysees of Christoph Gluck (1714-1787). His biographer Robert Payne observes that these were ‘were admirable selections, for they convey a sense of heavenly mysteries and the divine presence, but Gandhi, immersed in the rhythms of Indian music, remained unmoved and detached’,17 but another gifted biographer displays a different awareness of the cultural politics of Rolland’s choices: ‘Apparently these pieces reflected his own concept of Gandhi. One notes the limitations of the pacifist [Rolland]. If Beethoven’s symphonies contain any echo of this particular Great Soul and his career, it is surely in the first movement of the Ninth.’18 Mirabehn recounts the meeting but only quotes Rolland’s observations without comment: if there is any disappointment, it is not shared with the reader. She may, in the event, have been heartened by Rolland’s further observation’s about Gandhi’s tastes in music: ‘He is very sensitive to the religious chants of his country, which somewhat resemble the most beautiful of our Gregorian melodies and he has worked to assemble them.’19

Rolland’s own preoccupations with both the music of Beethoven and Indian philosophical thought were perhaps prefigured in some strands of German and European intellectual history. It may yet be possible to take a more complex view of the transcendent links that brought India to Beethoven and in turn augur what one hopes will be a new phase in the long narrative of India’s propensity to parley with the infinite. India occupied a very prominent place in the German imagination in the late 18th century and early 19th century and the names of Goethe, the philosopher Schopenhauer, the philosopher, poet, Indologist, and linguist Friedrich Schlegel, and the Sanskritist August Wilhelm Schlegel, to name just a few intellectuals, come up frequently.20 Beethoven has seldom been mentioned in this connection, but his Tagebuch, or notebook which he kept from 1812-1818, suggests that Beethoven’s interest in India was something far more than perfunctory and possibly just as profound as that of his peers.

![]()

It is now clear, as studies of the Tagebuch have shown, that he had an intimate familiarity with Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, upon which Goethe had lavished encomiums and which was quite the rage in Germany, as well as with Charles Wilkins’ translation into English of the Bhagavad Gita (to which Warren Hastings added a preface as remarkable as any ever penned by a member of a ruling class to a work belonging to the colonized), the writings of Sir William Jones, and William Robertson’s An Historical Disquisition Concerning the Knowledge Which the Ancients Had of India (1791). The deaf composer found inspiration, too, in the blind Homer, quoting from the Iliad (22: 303-5):

Let me not sink into the dust unresisting and inglorious,

But first accomplish great things, of which future generations too shall hear!21

Stunningly, this quote from the Iliad is preceded in Beethoven’s notebook by an excerpt from the Gita that he took to be its central teaching:

Let not thy life be spent in inaction. Depend upon application, perform thy duty, abandon all thought of the consequence, and make the event equal, whether it terminate in good or evil; for such an equality is called Yog, attention to what is spiritual.22

An equally arresting, and no less compelling, strain of thought that suggests what ties Beethoven to Indian philosophical traditions and to what I would like to call Indian ideas of the sensorium is to be found in the work of the scholar David Tame. Much has been written on the fact that Beethoven’s deafness became progressively worse—and that somehow he was able to marshal his inexplicable gifts to continue writing music that he could not hear and that he yet heard all too clearly as if he had been struck by a mystical vision of the divine. To Tame, however, there is no mystery here: as he explains, ‘The loss of one’s perceptive faculties has symbolic and mythical overtones in mysticism. In raja yoga, concentration and samadhi are achieved partly by cutting off one’s awareness of the senses.’23 As Beethoven’s malady worsened, and his awareness of the outer world diminished, he came closer to the attainment of divine union. Tame is of the view that Beethoven’s very understanding of music as the release ‘into the material world [of] a fundamental, superphysical energy’ is anticipated in the Vedic notion of ‘divine vibrational force—referred to as the OM—[as] the source of all matter and all creation.’24

A few years after the notebook’s last entry in 1818, Beethoven would go on to write what are justly viewed as his greatest musical compositions and quite likely among the most sublime works in the entire repertoire of Western classical music. In their own day, the late string quarters (numbers 12-16 and the Grosse Fuge) were viewed askance, as nearly incomprehensible and confused works. Beethoven’s contemporary, the composer Franz Schubert, was almost singular in recognizing that the late string quartets were perhaps an expression of the ineffable in human existence and the search of the soul for the transcendent. Listening to the String Quartet No. 14 in C minor (Opus 131) for the last time, just before his death, Schubert exclaimed, ‘After this, what is left for us to write.’25 Opinion would begin to swing the other way many years after Beethoven’s death, but what is singularly striking is that musicologists have been loath to consider how Indian philosophy may have contributed to carving out in Beethoven’s frame of thinking a space for the melancholic longing for the liberation that the Buddhists describe as nirvana and the Hindus as moksha. After the Upanishads and Shankaracharya, Beethoven has given us the music of advaita.

![]()

*******

1Author’s Notes See, for example, this blog from the American Philatelic Society (29 January 2021): https://stamps.org/news/c/collecting-insights/cat/opinion/post/stamp-collecting-has-soothed-presidents-can-it-do-the-same-for-you 2 For a discussion of these issues, see Hao Huang, ‘Why Chinese people play Western classical music: Transcultural roots of music philosophy’, International Journal of Music Education (2011), 1-16, doi: DOI: 10.1177/0255761411420955 3 Viktoria Elisabeth Kaunzner, ‘Melancholy and perfectionism: South Korea’s love of western classical music’, The Strad (9 April 2014), online: https://www.thestrad.com/melancholy-and-perfectionism-south-koreas-love-of-western-classical-music/3763.article 4 Priya Chaturvedi, ‘Philomena Thumboochetty: Portrait of an artiste’, Serenade (11 June 2019), online: https://serenademagazine.com/features/philomena-thumboochetty-portrait-of-an-artiste/. Serenade describes itself as India’s first and only ‘Western classical music portal’. 5Shubha Mudgal, ‘Menuhin Memories’, Mint (16 September 2016), online: https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/yG32Z4WBuoovCc6GCGhcvL/Menuhin-memories.html 6 Cited by Luis Dias, ‘Yehudi Menuhin birth centenary: How India shaped the legendary violinist’, scroll.in (22 April 2016), online: https://scroll.in/article/806878/yehudi-menuhin-birth-centenary-how-india-shaped-the-legendary-violinist 7See, for example, Walter Riezler, Beethoven, trans. from the German by G. D. H. Pidcock with an introduction by Wilhelm Furtwangler (New York: Vienna House, 1972 [1938]), 136-37. 8 The manuscript title page is reproduced in Romain Rolland, Beethoven the Creator, trans. Ernest Newman (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1929), between pages 62 and 63. 9Esteban Buch, Beethoven’s Ninth: A Political History, trans. Richard Miller (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003). 10Sudheendra Kulkarni has spun a fat volume from this idea: see his Music of the Spinning Wheel: Mahatma Gandhi’s Manifesto for the Internet Age (New Delhi: Amaryllis, 2012). 11Sudheendra Kulkarni has spun a fat volume from this idea: see his Music of the Spinning Wheel: Mahatma Gandhi’s Manifesto for the Internet Age (New Delhi: Amaryllis, 2012). 12Cynthia Snodgrass, The Sounds of Satyagraha: Mahatma Gandhi’s Use of Sung-Prayers and Ritual, Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Stirling (2007), online at: https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/555/1/Sounds%20of%20Satyagraha.pdf 13Romain Rolland, Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One with the Universal Being, trans. Catherine D. Groth (New York and London: The Century Co., 1924). 14 Madeleine Slade, The Spirit’s Pilgrimage (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1960), 61, 66. 15Mirabehn’s unfinished manuscript was published as Beethoven’s Mystical Vision (Madurai: Khadi Friends Forum, 1999), but is nearly impossible to find and I have yet to lay my hands on a copy. 16 The letter is quoted at some length in D. G. Tendulkar, Mahatma: The Life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, 8 vols. (reprint of revised ed., New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, 1969), 3: 150. 17Robert Payne, The Life and Death of Mahatma Gandhi (reprint ed., New York: Smithmark, 1996 [1969]), 424. 18Geoffrey Ashe, Gandhi (New York: Stein and Day, 1969), 312. 19Slade, The Spirit’s Pilgrimage, 149; Tendulkar, Mahatma, 3: 150. 20One of the best and lengthy introductions to this subject is Raymond Schwab, Oriental Renaissance: Europe’s rediscovery of India and the East, trans. G. Patterson-Black and V. Reinking (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984). 21Quoted in Maynard Solomon, Late Beethoven: Music, Thought, Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 6. 22These verses from the Gita are quoted by Warren Hastings in his preface to the first English translation of the text by Charles Wilkins, The Bhagavat-Geeta or Dialogues of Kreeshna and Arjoon (London: C. Nourse, 1785). 23David Tame, Beethoven and the Spiritual Path (Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 1994), 32. 24 Ibid., 6. 25Cited by Zachary Woolfe, ‘At Mozart Festival, Dvorak and Others Shine’, New York Times (8 August 2011).

Vinay Lal is Professor, History at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), United States. A sample of his extensive writings: Political Hinduism: The Religious Imagination in Public Spheres. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.India and the Unthinkable: The Backwaters Collective on Metaphysics and Politics. Co-edited with Roby Rajan. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016. A Passionate Life: Writings By and On Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay. Co-edited with Ellen C. DuBois. Delhi: Zubaan Books, 2017.Blog:https://vinaylal.

wordpress.com/ Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/ dillichalo More by Vinay Lal in The Beacon Vaishnavajana to: Notes on Gandhi, Bhakti, and Narsi Mehta Visions of an Insurgent Spirit: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay on the ‘Global South’ The Ayodhya Verdict: What it means for Hindus Gandhi’s Dharma: Itineraries of a Religious Life

I enjoy music…eclectic as it may be. But this piece by Vinay Lal prompts me to set aside ‘me from myself’. In its simplicity the writing entices one to visit the well written chapters of Beethovan, anew. It promises much. It promises much!

I seem to have missed this well-informed, intelligently argued and empathetic article. The Mahatama continues to surprise me as I find his inquiring mind continuously seeking and nurturing the finest imaginative impulses wherever he finds them — villagers singing bhajans, simple potters, painters, Charlie Chaplin, Romain Rolland and Victor Hugo ( a connection yet to be examined) or Bade Gulam Ali Khan — and leaving his own special mark on each.