Cheri Jacob K.

“Enthaayaalum Oru Aathmeeya Unarvundallo, mmm?” “Oh, Aatmeeyathede mayiru.” [All said and done there is a spiritual freshening, ain’t there? / Well, spirituality’s dickhead’] –

L

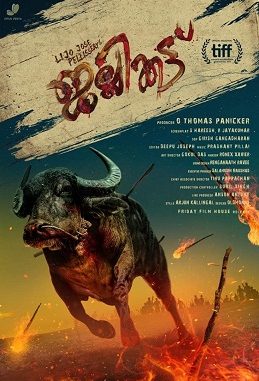

Lijo Jose Pellissery ends the official trailer to his yet-to-be-released film Churuli [Vegetable fern/Helix/Spiral] thus. In a certain sense, one can treat this tete-a-tete as some sort of a summing up of the huge accolade that his film Jallikkettu has received; a summing up in the sense that Jallikkettu as a film hits you in the raw, even when it retains a choreographed finesse that gives an apparent feel of ‘packaged-to-international-standards’ craftsmanship. And the critical baggage that has emerged like a spiral around the film too seems to be addressing the film’s orchestrated irreverence and off-beat-halo with a taciturn reverence that only slightly falls short of a new-found spiritually [filmic] refreshing awe!

Taking a cue from the makers of Jallikkettu, this meandering, rambling musing ‘irreverently’ puts forward a hypothesis disguised as a title: ‘Battle-slip Poten-kin: Jallikkettu as an (un)easy ‘pleisure.’’ Pleisure, George Torkildsen’s portmanteau word that signifies ‘Please Oneself + Leisure’, two affective states that this film evokes in abundance in quite a few sections of the film-viewing fraternity; Poten-kin, a willfully-corrupted rendition of Eisenstein’s politically charged and ever-relevant classic, an allusion to the way Jallikketu ‘mutes’ the probable immensity of a could-have-been-possible politics – loosely akin to the way the Pottan-Theyyam [Onappottan] in Kerala plays out its ‘politics of verbal-muteness’ – and yet aspires to and lures us into believing that there is indeed a certain ‘kin’ link (to all filmic battles of Bravehearts) within which a psychic ‘battle’ is being waged in the primeval terra incognita of the id/unconscious; and in this always already staged (even in terms of film historiography) battle, there is a slippage – hence the convoluted coinage ‘battle-slip’ – which creates an indeterminacy as to how we are to take in and then (over)interpret the dazzling cine-work. By way of an analogy, the following figuration is being offered: Jallikkettu is the film Pulimurukan in reverse! Here, the camera is Murugan on the hunt; and we are the hunted – we are asked to shed all our niceties and pretences and ‘assume’ the consensus regarding the critical essence/core philosophy that the film arguably puts up for consumption/discussion: aggression, lust for flesh, inherent savagery, the primitive in the civilized, time primordial, so on and so forth. And in the end the ‘pleisure’ that oozes out is not definitive; there is something uneasy about it – both for the cineaste and for the masses.

Be that as it may, one thing about Jallikkettu is that it has so far gained an endorsement that legitimizes the work as a ‘must watch’; from being the official Oscar entry from India and the Golden Globe Handshake, the film has had a brilliant run. Perhaps one can discern a certain ‘imbibing’ and ‘appropriation’ of a certain hidden, standardized Oscar Template. Oscar and India: Mother India, Salaam Bombay and Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India; India’s three Oscar nominations (so far) have one thing in common – poverty (also, Slumdog Millionaire!) Also, all these films are in a sense ‘historically materialistic’, but Jallikkettu steers clear of this terrain and posits itself as ‘psycho-analytic.’ This is evident right from the title, which throws one off the scent as to the subsequent content of the film. The preferred reading of this word is the human-animal sport but here it seeks to emerge as some sort of a metaphor-cum-metonymy that highlights human bestiality and the power-hunter trope.

In fact the film’s title is a transgression which exposes and then endorses the status quo with regard to violent human aggression.

Seen this way, the manner in which the title invites us to enter the film’s diegesis is uncannily close to the arguments in Anthony Julius’ book Transgressions: The Offences of Art. Julius frames ‘offence’ as ‘rule-breaking, including the violation of principles, conventions, pieties, or taboos; the giving of serious offence; and the exceeding, erasing or disordering of physical or conceptual boundaries…transgressing the laws both of perspective and morality.’ This film too manages to conjure up one such grim cacophony. Away from the actual sport itself, it deals blatantly with chaos: a water buffalo escapes a butcher’s clutches and then there is this build up where a whole mob-village/village-mob is maniacally in pursuit; this primary thread is embellished with a chilling voyeuristic peep into quite a few of the villagers’/characters’ lives, thereby revealing man’s innate bestial side, from time immemorial.

And yet, there is a sleek richness to the frames. And this richness prompts the question: In a broad sense, does Jallikkettu qualify as Film Noir? That too, a Noir bereft of the trappings of the (un)civilized city? Perhaps the answer is ‘yes and no’. But the issue here is that, in a neo-Foucauldian way, a rampant sense of power and domination is marvelously played out. The only difference is that here power is maintained at the physical level of violence and exertion where the psychological manipulation of power from within the body is in a sense visceral and (in)voluntarily. This discourse of dominance and savagery remains as a ‘trace’ in this film. Rather, the cinematography drastically imposes the dominance-discourse and subjugates the viewers’ minds by putting up dramatized illusions as dominant meanings through the tricks of montage, close-ups, assembly, and gaze; in fact, the movie accentuates a ‘fear of others,’ by harping on eventual (individual) alienation, isolation, and a lack of dialogue, which in turn are effective in inciting violence and which get highlighted by the use of the cut or transition. The cuts are lightning fast – one should possess a split second cognition; you feel you are hurtling downhill. It may be said that this disorienting/dislocating is a deliberate cinematic blow. And yet, it is here that the specter of Potemkin, especially the Odessa Steps looms up as a questioning apparition! And we are left uneasy because this assemblage has a frenzied joy that makes the claim of a film having to ever ‘mean,’ redundant! Rather, the core of the narrative is an energetic absurdity! Camus’ Absurd? – Well, let me leave that open.

This feel has a lot to do with Music/Sound pattern: Clocks ticking like Thor’s hammer-blow, human breathing that stays so very close to a dragon’s hiss (Smaug in The Hobbit), Gothic choruses indulging in some sort of a pre-linguistic primitive chant – taken together, we are submerged in a tantalizing orchestration that is more real than the actual real! This strain loops back into the issue of Film Noir.

In a big way Jallikkettu sets the audience up to accepting its dark style of filmmaking replete with cynical heroes, stark lighting effects and somber sounds; a cinema of the disenchanted that increases contrast through the use of shadows and dark tones – usually dramatic and full of mystery.

One possible path to tread while writing about the film is to go ‘gaga’ over the film’s quasi-kinship to Experimental cinema. For Dominique Noguez such cinema is a cinema of irreverence and ‘irreference’; and it refuses the conventions and the analogical imprint indexed on dominant mainstream cinema. It is a cinema of apparition more than of appearances; appearing, in effect, to comply with all the characteristics of the figural: a cinema which refuses mimesis, representation, narration (which the recognition of figures implies: what do they go on to become?).

Jallikkettu does possess such flashes that will seduce us into believing that this is indeed true at the instance of viewing. And yet, somewhere it refuses to further this experiment to an extent where it can be called ‘acinema’ in the way Jean Francois Lyotard conceives it. For Lyotard ‘acinema’ is the negation (a-) of the majoritarian (industrial, commercial) cinema, that is to say of the cinema norm, where the movement (kinêma) and the image are neutralised in a middle range acceptable to the largest number of viewers. Lyotard’s acinema is cinema which accepts ‘what is fortuitous, dirty, confused, unsteady, unclear, poorly framed, overexposed’: intensities, timbres, nuances, colours, drips, bursts, breaks, scratches, cuts, openings. In a word, the energetic: the tenuous, the unstable and shifting, which always escapes the deterministic and reductive constructions of the well-formed.

Indeed Jallikkettu simulates, in a straight-at-your-face way, quite a few of these traits, and yet…

Reflections on Jallikkettu often veer into the bold honesty of the ethic of the film regarding its mapping of aggressive and hierarchical patriarchy. The film refreshingly, albeit grimly, reminds us that all men are beasts: for instance, the man who slaps his wife for having made puttu again; the men who prey on each other; or the men who arrive from neighboring villages, fuelling the chaos and the hatred; the undertone that the hunter-gatherers are still running amok; as one old man comments, “It’s just that they tread on two limbs. They are all still animals”. A pertinent point here is that the women in the movie do not take part in this mad chase. This division of labour is at the core of Jallikketu’s patriarchal content. It is an honest take, all right. It denotes, but does it connote?

There is a negativity at play here. But does it ‘deconstruct’ the filmic dominant? Julia Kristeva conceives such an act thus: “The issue of ethics crops up wherever a code must be shattered in order to give way to the free play of negativity, need, desire, pleasure and jouissance, before being put together again, although temporarily.” Jallikattu as an allegory performatively proclaims that it is ripping apart the facade of civilisation. And then?

I am put in mind of Gayathri Spivak’s Preface to Göran Olsson’s documentary Concerning Violence: Nine Scenes from the Anti-Imperialistic Self-Defense. She says, ‘I add a word on gender. This film reminds us that, although liberation struggles force women into an apparent equality – starting with the 19th century or even earlier – when the dust settles, the so-called post-colonial nation goes back to the invisible long term structures of gendering…At the intersection between the vision of a real object and hallucination, the cinematographic object brings into the identifiable (and surely nothing is more identifiable than the visible/seeable) that which remains beyond identification: the drive unsymbolized, unfixed in the object-the sign-language, or, in more brutal terms, it brings in aggressivity.’

But this visibilisation of aggressivity ideally should bring along a gender sensitive ethics-coda. Curiously, Jallikkettu stops a few steps short of such a terrain. Its stance is more akin to what Roland Barthes, in ‘En sortant du cinema [Leaving the cinema]’, qualifies as a ‘jouissance of discretion’ – solitary auto-erotic pleasure; narcissism and a fetish for dormant violence: cinema as a homo-social/sexual cocoon/closet. Such a male bonding is much more than evident within (and behind the scenes!) in Jallikkettu.

Viewed thus Jallikkettu qualifies as well-packaged Bad cinema, in a strictly Deleuzian sense. In an interview, Deleuze states his belief in the need for a separation between the commercial and truly creative cinema. ‘Bad cinema always travels through circuits created by the lower brain: violence and sexuality in what is represented – a mix of gratuitous cruelty and organized ineptitude.’ Does not Jallikkettu ring a bell?

Here it would be pertinent to be reminded of the Oscar-Golden Globe nominations that the film has bagged. How close or distant does this label make Jallikkettu to the ‘Third Cinema’ of Solanas and Getino?

As is evident, Third Cinema, also called Third World Cinema, was/is an aesthetic and political cinematic movement in Third World countries (mainly in Latin America and Africa) meant as an alternative to Hollywood (First Cinema) and aesthetically oriented European films (Second Cinema). It was a cinema rooted in Marxist aesthetics generally and specifically inflected by the socialist sensibility of German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, the British social documentary developed by producer John Grierson, and post-World War II Italian Neorealism.

Third Cinema went beyond even these predecessors and called for an end to the division between art and life and insisted on a critical and intuitive, rather than a propagandist, cinema in order to produce a new emancipatory mass culture.

What about Jallikkettu?

And yet Jallikkettu is like (dark) chocolate – yummy, yummy! There is a surface glitter that takes me back once again to Roland Barthes; especially to Barthes’ eye for the sensuous surface of things; something which can be called the ‘micropolitics’ of film. This micropolitics finds expression in ‘a kind of egalitarian cinematic gaze, in an aesthetic sensibility intent upon exploring the inexhaustible fascination with the ordinary. This angle identifies the revolutionary potential of a film not strictly in its story, message, or even style, but rather in its fractions and particles, in those miniature, fleeting, fortuitous, or seemingly insignificant elements that nonetheless manage to transmit to viewers . . . new conceptions of being a body, of linking one gesture to another, of moving in space, of being together.’ Barthes here is no longer under the impression that the power of cinema resides ‘in its capacity to hypnotize or render us passive,’ but rather in its ‘ability to transform the sensory experience of the world around us.’

Somehow, as though in line with these observations, Jallikkettu possesses several teeny-weeny sub-plots that come along with the main men-beast-chase: for instance, the young couple trying to make its escape but get caught when the boy’s two-wheeler gets grounded and the girl’s father orders her back home; or the old man dying in his bed, guarded over by a tired middle-aged man. These snippets acquire a sensory sensuousness, a rustle, as Barthes would remark, that literally infects the viewer. This for one is a major USP of Jallikkettu.

At the cost of a travesty, allow me to say that the ending of the film Jallikkettu was precisely predicted, quite a while ago, by none other than Salman Rushdie. I am referring to the ‘freeze-frame (and to me ‘tame’) abruption – A pile of humans fusing and constellating into one compound beast-pyramid; a frame and a visual that does not quite gel into the rest of the visual narrative; a final composite semiotic thematic that is not enabling. Oops, I forgot Rushdie! Salman was highly annoyed by the ending of the film The Wizard of Oz. Waking up again on her bed in good old Kansas, Dorothy declares, “If I ever go looking for my heart’s desire again, I won’t look further than my own backyard. And if it isn’t there, I never really lost it to begin with.” This is an encomium to staying put. ‘How does it come about,’ Rushdie asks, ‘at the close of this radical and enabling film, which teaches us in the least didactic way possible to build on what we have, to make the best of ourselves, that we are given this conservative little homily?’

How could anyone renounce the colorful world of Oz, Rushdie wants to know, the dream of a new and different place, for the black and white comforts, the utter drabness of Kansas and all the homespun hominess it represents?

Something similar, but in a different tenor, happens in Jallikkettu: The hunted bull is finally swamped in mire; enraged and famished men pounce upon it, but the chaotic weight sinks the bull, killing it. And from this mud-slush heap Antony attempts to push out but gets sucked in. What is this scene connoting in terms of a closing vision? Perhaps, at this point of finishing off the diegesis Jallikkettu is freezing a situation in which life is reduced to ‘bare life’ and in which the already weakened link between bare-life self and society collapses into itself – a mise-en-scene of auto aggression.

However, there is no hint of a cinematic redemption like the one Roland Barthes (again!) teases out from Eisenstein’s film Ivan the Terrible. Barthes talks about ‘the third, meaning’ which several Eisenstenian frames conveyed to him. He takes recourse to geometry and says, ‘An obtuse angle is greater than a right angle: an obtuse angle is of 1000, says the dictionary; the third meaning also seems to me greater than the pure, upright, secant, legal perpendicular of the narrative, it seems to open the field of meaning totally.’ And then Barthes puts forth three orders of meaning in a film shot: the informational, the symbolic, and the signified: emotion-value. It is at this third level of meaning, says Barthes, that the filmic emerges – the content of film that cannot be described verbally.

Jallikkettu, in the formal design of its last scene, falls very much into this pattern. Moreover, in a Lacanian sense, what happens at this points of encounter marked by a culminating act of immediate aggression, even though it is choreographed, be they contingent and ritualized are examples of a ‘passage to the act’ – an exit from the symbolic network, a dissolution of the social bond. The subjects acting out are not psychotics, but even then there is a dissolution of the subject(s); in that instance the subject becomes a pure object – for the camera – This is the libidinal economy of the ending of Jallikkettu!

This ending also fulfills the demands of what Noel Burch calls the Emblematic shot at the very end: a reverse-establishing shot that creating an ocular contact between actor and spectator; a form of suture that is attempting a narrative closure; a meaningful, constructed and signaled ending – and yet, this ending lingers and resides at the level of a howling/screaming bestiality, just like that; and hence its tameness.

By way of a tentative analytical closure, allow me to state that at its barest (and broadest) level Jallikkettu is about death; obviously not of cinema or the auteur but perhaps of film theorizations/critiques/writings. A pessimist might say: Death? So what? I knew that already. And such a person can perhaps cite Laura Mulvey who elaborately discusses film’s relationship to death in her book Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image. In it, she writes: ‘For human and all organic life, time marks the movement along a path to death, that is, to the stillness that represents the transformation of the animate into the inanimate. In cinema, the blending of movement and stillness touches on this point of uncertainty so that, buried in the cinema’s materiality, lies a reminder of the difficulty of understanding passing time and, ultimately, of understanding death.’

Despite its inability to move beyond the logic and the cliché of the filmic/popular dominant, somewhere, right at the very end of Jallikkettu, one comes face to face with this very stillness. A stillness which whispers the actual actuality of the film’s essence: ‘Life is a tale, told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’

Sorry William, did you know that we just discovered we guys are all beasts?!

*******

References Anthony Julius, Transgressions: The Offences of Art, University of Chicago Press, 2003 David Martin-Jones, Deleuze and Film, Edinburgh University Press, 2006 Dominique Noguez, Cinema: Theories, Lectures, Klincksieck, Paris, 1973 Gayatri Spivak, Preface to Göran Olsson’s documentary Concerning Violence: Nine Scenes from the Anti-Imperialistic Self-Defense, Film Quarterly, Fall 2014, Volume 68, Number 1. Graham Jones/Ashley Woodward (eds), Acinemas: Lyotard’s Philosophy of Film, Edinburgh University Press, 2017 Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language, Columbia University Press, 1984 -- ‘The Subject in Signifying Practice’, Semiotext(e), 1: 3, New York. Laura Mulvey, Death 24 x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image, Reaktion Books, London, 2006 Michel Foucault, The Will to Knowledge: History of Sexuality – Vol 1, Penguin, London 1998 Noel Burch, Life to Those Shadows, London, BFI Publishing, 1990 Roland Barthes, ‘En sortant du cinema [Leaving the cinema]’ in The Rustle of Language, Blackwell, Oxford, 1986. --‘The Third Meaning’ in Image Music Text, Fontana Press, London, 1977 Salman Rushdie, The Wizard of Oz, BFI Film Classics, London, 2008 Solanas and Getino, ‘Toward a Third Cinema’, Cineaste, Vol 4, No, 3, Winter 1970-71

Cheri Jacob K. is Assistant Professor [stage 2] in the Department of English, Union Christian College, Aluva. He is winner of the Kerala State Film Award for the best article on cinema [‘Sepia: Nirangalude Soundarya-raashtreeyangal’ (Political-Aesthetics of Colour)] in 2012 and for the best book on cinema [Cinema Muthal, Cinema Vare (From Cinema, Till Cinema)] in 2016. He is awaiting the valuation report of his PhD thesis [Elsewhere/Nowhere: Spatiality and Fictional Emplacement] which focuses on the different emplacements that select Shakespearean plays have had in Hindi and Malayalam Cinema. He is an ‘off and on’ translator from Malayalam to English, especially for the journal Indian Literature, published by the Kendra Sahitya Academy [National Academy of Letters]. His areas of interest include, Film Studies, Cultural Studies, Adaptation Studies and Translation Studies. He hails from Olassa, Kottayam, Kerala. cherijacob@gmail.com

Leave a Reply