Mohammad A. Quayum

Introduction

R

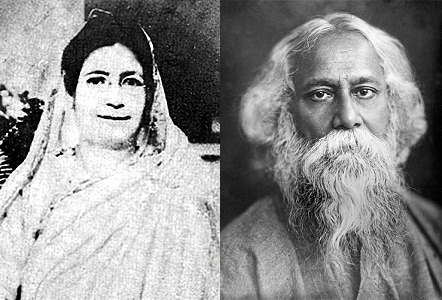

abindranath Tagore (1861–1941), Asia’s first Nobel Laureate, and Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880–1932), one of British India’s earliest Muslim feminist writers, were contemporaries in Bengali literature and are two of the most acclaimed writers of the Bengal Renaissance during the early twentieth century. They were born and raised in very different socio-cultural and religious environments. Tagore hailed from a financially well-off and culturally rich Hindu-Brahmo-Brahmin zamindar family in Calcutta, while Rokeya was born into a similarly well-to-do but relatively conservative Muslim zamindar family, in a small village in the north of East Bengal, now in Bangladesh.

Tagore was primarily a poet, though he wrote in other genres as well. Rokeya excelled in polemical prose, but wrote poetry and fiction too. Tagore was more of a romantic writer who saw reality through the eyes of a visionary and an idealist. Although social reform was an important aspect of his writing as well, he did not compromise his art tobecome a teacher or give ‘moral lessons’ (Das, 1996: 737, 741). Rokeya, on the other hand, saw the edification of readers as the primary function of writing. To her, literature was essentially a tool for reforming and improving society (Hossain, 1992: 17). Tagore considered imagination and emotion to be his guiding stars, Rokeya celebrated reason and logic.

A natural poet, Tagore wrote in florid and figurative language even in his prose, for which he was once forced to defend himself against charges of grandiloquence by his critics (Tagore, 2008: 850–1). Rokeya always wrote in an ostensibly simple and transparent style, using familiar diction, simple sentences and deliberately unadorned prose. Tagore’s objective was to arouse the reader’s imagination and passion. Rokeya’s was to appeal to her readers’ intellect and influence their judgement through a compelling train of thought.

Both of them lacked formal education, both became ardent champions of education. Tagore considered education as a major step towards India’s freedom and the assertion of her moral authority on the global stage. Rokeya saw the redemption of Indian women, more specifically of Muslim women in South Asia as central. To express their convictions in the redemptive power of education, Tagore built Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan in 1921, while Rokeya established a school for girls in Calcutta in 1910, Sakhawat Memorial School for Girls, named after her husband.

Most significantly, despite their different religious identities, both writers stepped out of their cultural borders to embrace the ‘other’ in a spirit of fellowship and unity, against a backdrop of turbulent Hindu–Muslim relationships and recurrent communal riots,1 through most of their adult lives.

Both believed that creating Hindu–Muslim amity and unity was fundamental to the creation and survival of the internally plural Indian nation. Both were thus respectful in their interactions with and representation of members from the ‘other’ religious–cultural community. It could be said that they took a humanist and secular approach, though the meaning of the latter term remains deeply contested even today,

The Importance of Biographies

To understand how and against what grave odds these two writers came to espouse such a cross-cultural outlook and to champion the value of religious unity one should begin with their biographies. Tagore as is well known, was born into a culturally advanced and rich zamindar Hindu–Brahmin family in Calcutta in 1861, only four years after the outbreak of a revolt by Indian soldiers against the East India Company. Tagore’s grandfather, ‘Prince’ Dwarkanath Tagore (1794–1846), a leading industrialist of his time, was held in ‘very high esteem and affection by Queen Victoria and the nobility of England’ (Kripalani, 1962: 22).

However, Dwarkanath’s son, and Tagore’s father, Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905), was a spiritually inclined individual who contributed to a reformist religious movement, Brahmo Samaj,2 which sought to revive the monistic basis of Hinduism as laid down in the Upanishads. Tagore’s sister Swarnakumari Devi (1856–1932) was one of the first women novelists in Bengal. The rest of the family were equally gifted in literature, music, art, philosophy and mathematics, such that the family ran a literary journal of its own.

Despite such an outstanding background, Tagore never had any formal education in childhood. Instead of being sent to school he was educated at home. Although he went to England at the age of 17 to study Law at the University of London, he returned home a year later without completing his studies. This alternative mode of education was perhaps a boon, as it would have helped Tagore to elude the dominant religious stereotypes of his society, often passed down to children through the mainstream education system. Moreover, Tagore was influenced by his father’s reformist outlook. Like his father he was interested in revising and reinventing Hinduism by ridding it of its fatuous traditions and meaningless rituals.

Although Tagore’s father lost much of the family wealth accumulated by Tagore’s grandfather owing to his impractical and idealistic nature, the family still had large landholdings in three different places in what is now Bangladesh. In November 1889, Tagore was appointed by his father to oversee this family property. This at once brought him into close contact with poor tenant farmers, most of them Muslims cultivating the family’s lands. Tagore spent more than ten years (1890–1901) living with these tenants in East Bengal and possibly this particular experience helped him rise above the prevailing ‘dusty politics’ (Tagore’s own phrase) of communal hatred. It enabled him to understand and appreciate the culture of those Muslim tenants, and by extension, the culture of Islam. In a letter to a Bengali woman friend in 1931, the daughter of an orthodox zamindar family from Natore in East Bengal, Tagore declared in simple but pointed language: ‘I love [my tenants] from my heart, because they deserve it’ (Dutta & Robinson, 1997: 405).

As Novak (2008 [1994]: 118–9) points out::

Interested in politics only insofar as it concerned the deeper life of India, he espoused mildly communistic ideas, though not necessarily Marxist ones, wanting the nationalist movement to consider social reforms before political freedom, actively opposing the Bengal partition, and endorsing the peaceful aspects of the countermovement to keep Bengal in one piece.

Compared to Tagore, Rokeya’s life, as a woman and a Muslim, was far more challenging, laced with additional difficulties. Born in 1880 into a conservative Muslim family, she grew up not in metropolitan Calcutta like Tagore, but in a small village called Pairaband, in Rangpur district, now in northern Bangladesh. Rokeya’s father, Zahiruddin Muhammad Abu Ali Hyder Saber, was a zamindar, like Tagore’s. But he was wasteful and extravagant; he lost his entire inheritance long before his death incurring huge debts and lived the remaining years of his life in hardship and poverty.

Moreover, Rokeya’s father was an orthodox man who did not believe in an academic education for his daughters apart from learning the Qur’an by rote without knowing its meaning. Tagore’s family valued knowledge and culture, creating a positive influence on the young boy, Rokeya’s father barred his daughter even from learning Bengali and English. Abu Ali Saber himself read and spoke several languages, including English; he even took a European woman as his fourth wife (Ray, 2002: 17). Yet he did not want Rokeya to learn English, because in those days Muslims viewed this as detrimental to Islamic teachings and the Islamic way of life. Moreover, he did not want his daughters to learn Bengali because the aristocratic ashraf Muslims at the time saw Arab and Persian traditions as authentic Islamic culture and treated local traditions and languages, as un-Islamic (Ahmed, 2001: 9). Bengali was looked down upon as a ‘non-Islamic inheritance’ (Ahmed, 2001: 6), spoken mainly by Hindus and those lower-class atraf Bengali Muslims who had converted from Hinduism.4

If this was not enough, Rokeya was also brought up in the strictest form of purdah practiced by elite Muslims at that time. She was not allowed to interact with men or even women outside her family circle from the age of five. In several episodes of her book The Zenana Women (Aborodhbashini), especially in episode 23, Rokeya sarcastically portrayed how she had to go into hiding in her own home whenever an unknown woman walked into their courtyard or came to visit. A victim of this purdah system, she became its severest critic in later years. For example, in her essay, ‘Bengal Women’s Educational Conference’ (Quadir, 2006: 227; my translation), Rokeya wrote:

Although Islam has successfully prevented the physical killing of baby girls, yet Muslims have been glibly and frantically wrecking the mind, intellect and judgement of their daughters till the present day. Many consider it a mark of honour to keep their daughters ignorant and deprive them of knowledge and understanding of the world by cooping them up within the four walls of the house.

In another passage of the same essay, purdah practices of the time are compared to carbonic acid gas which kills its victims silently and without causing any physical pain. Rokeya (Quadir, 2006: 229, my translation) wrote scathingly: “The purdah practice can be compared more accurately with the deadly Carbonic acid gas. Because it kills without any pain, people get no opportunity to take precaution against it. Likewise, women in purdah are dying bit by bit in silence from this seclusion ‘gas’, without experiencing pain.”

Despite such challenges and obstacles that left her with virtually no options in life other than to become a traditional Muslim housewife, Rokeya grew up to become a writer in both Bengali and English. She came to embrace a view of life that was utterly contrary to the insular and parochial lifestyle in which she was brought up during her childhood. In later life, she not only became a fierce critic of social segregation of sexes and excessive purdah, but also a champion of unity between various racial and religious groups in the subcontinent.

This was probably made possible through the benevolent and salutary influences of three people in her life: Karimunnesa Khatun, her elder sister; Ibrahim Saber, her elder brother; and Khan Bahadur Syed Sakhawat Hossain, her husband. Reading through the works of Rokeya, one finds that she did not have much to say by way of expressing gratitude to her parents. Rather she gives full credit to these three people for whatever success she attained in life.

Rokeya learnt Bengali from her elder sister Karimunnesa Khatun, to whom she later dedicated the second volume of her book Motichur (1922). In her dedicatory note to this book, Rokeya explains that without the constant support and motivation from her sister, she could never have learnt Bengali or become a writer in the language:

I learnt to read the Bengali alphabets in childhood only because of your affectionate care…. I have not forgotten Bengali in spite of so many challenges… because of your care and concern and encouragement which have continued to motivate me to write in the language. (Quadir, 2006: 57, my translation)

Likewise, Rokeya learnt English from her elder brother, Ibrahim Saber, who used to tutor her secretly at night after their father had gone to sleep. Ibrahim Saber, brought up in an elite institution in Calcutta and later educated in England, also perhaps taught her to come out of the shadows of her father’s orthodox outlook and to perceive the world in a more modern and inclusivist spirit. In childhood, Ibrahim Saber came into contact with Dr K.D. Ghosh, father of the renowned philosopher, writer and nationalist leader, Sri Aurobindo Ghosh (1872–1950), when Ghosh was working as a civil surgeon in Rangpur. This probably had some effect in shaping his attitude towards Hindus generally, and indirectly influenced Rokeya as well in later years. As a mark of the overall influence her brother had on his younger sister, Rokeya dedicated her only novel Padmarag (1924) to Ibrahim Saber, in which she acknowledged:

“I have been immersed in your love from childhood. You have groomed me in your own hand. I have never experienced the love of a father, mother, an elder or a teacher. I have known you only…. Your love is sweeter than honey. Even honey has a bitter aftertaste, but yours is ambrosial; pure and divine like Kausar.” (Quadir, 2006: 261, my translation)

Rokeya’s husband too helped her overcome the closed, exclusivist world views of her father. Sakhawat Hossain was educated in England; like Ibrahim he was modern and progressive in his outlook. That Sakhawat was free of religious prejudice is evident from the fact that when he came to West Bengal to study at the Hooghly College, he became a close friend of Mukunda Dev Mukappadhay. Son of a renowned nineteenth century Bengali writer and philosopher, Bhudev Mukhapaddhyay (1827–1894), he helped Sakhawat, a man from Bihar, to learn Bengali.

Tagore’s Legacy

Tagore has left behind much evidence of his intention to unify the various racial and religious groups in India, part and parcel of his global imagination.5 He was interested in creating not only a holistic national identity for India but one identity for the whole of humankind. He believed that territorialism and provincialism were essentially animal instincts in the human being. Throughout his life, Tagore campaigned for a global society through the cultivation of fraternity and human fellowship.

His attempts to bring together Hindus and Muslims in India and to create an inclusive race (mahajati) were an important aspect of this philosophy. Tagore believed that one of the reasons for Hindus and Muslims being constantly at each other’s throats was their ignorance of each other’s culture, which induced bigotry in both groups. In a foreword to a book by a Muslim author (see Karim 1935 [1935]: 7), Tagore explained:

One of the most potent sources of Hindu–Muslim conflict is our scant knowledge of each other. We live side by side and yet very often our worlds are entirely different. Such mental aloofness has done immense mischief in the past and forebodes an evil future. It is only through a sympathetic understanding of each other’s culture and social customs and conventions that we can create an atmosphere of peace and goodwill.

Attempting to bridge this widening gap and to create a better and more sympathetic understanding between the two religious groups, Tagore introduced a Chair of Islamic Studies at Visva-Bharati in 1927 and a Chair of Persian Studies in 1932. Already in 1921, the year in which Visva-Bharati was upgraded from a school to a university, he started admitting Muslim students. In 1915, he translated many poems by the fourteenth-century poet Kabir into English. He also paid tribute to the Prophet of Islam on several occasions as a mark of respect and admiration for the religion and its followers. One such tribute describes the Prophet as ‘one of the greatest personalities born in this world’, while in another, after describing Islam as one of the few great religions of the world, Tagore went on to invoke the blessings of the grand Prophet of Islam for India, which, he wrote, ‘is in dire need of succour and solace’ (Das, 1996: 802).

Riots between Hindus and Muslims remained a common occurrence during this period as the British would often use religion to divide people. Whenever riots broke out, Tagore would pen letters in newspapers, appealing for calm and understanding on both sides. In one such letter to the Calcutta Statesman, written in 1931, in the wake of riots in Chittagong, Tagore urged Hindus and Muslims not to ‘indulge in mutual recrimination’ at the behest of the British, but ‘join hands…for the sake of bleeding humanity’, and for the fact that being ‘the children of the same soil, [they] will ever remain side by side to build up a commonwealth’ (Dutta & Robinson, 1997: 404).

It is true that Tagore did not depict many Muslim characters in his fictional work. This is not because he did not like Muslims or did not care to represent them in his writing. It is mainly because he knew that any criticism of Muslim culture, no matter how mild or well-intentioned, would only fan Muslim extremism.

Fiercely opposed to traditionalism and religious extremism, Tagore however attacked the outworn, degenerate and superstitious practices in Hindu culture over and again in his works. In many other writings he critiqued the Hindu caste system, child marriage, dowry practices, gender disparity and other evils associated with patriarchy and/or religious chauvinism and formalism. At the same time, Tagore consciously avoided such criticism in the case of Muslims, because he knew that such an approach would blur his mission of creating a religious mosaic in his homeland. Therefore, whenever he introduced Muslim characters in his work, albeit rarely, he portrayed them in a positive light, often pitting them against corrupt and retrogressive practices in the Hindu culture and/or community. This is particularly evident in those well-known stories, Kabuliwala’, ‘False Hope’ (‘Durasa’) and ‘A Woman’s Conversion to Islam’ (‘Musalmanir Galpa’).9

Rokeya’s Work

The spirit of potential fellowship, unity and togetherness that we observe in Tagore’s writings is also evident in the works of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. Rokeya wrote mostly for Muslim women since her primary focus was to redeem them from an abusive patriarchy that kept them utterly ignorant, socially segregated and financially dependent on men. However, she never lost sight of the larger objectives: the emancipation of all women, the necessity of a holistic national identity that unites all Indians; and, indeed, uniting all mankind for the sake of harmony, justice and peace. Although a practising Muslim who recited the Qur’an regularly and prayed five times a day,12 she had no prejudice against Hindus and often spoke in favour of Hindu women.

When she opened a school for girls in Calcutta in 1910, Rokeya had no clue about how to run a school, as she had never been to one herself. To gain experience in school administration, she would visit several Brahmo and Hindu schools in Calcutta, where she came in close contact with leading Hindu Bengali educationists of the time, such as Mrs P.K. Roy and Mrs Rajkumari Das, who became life-long friends. After Rokeya’s sudden and premature death on 9 December 1932, a memorial was held at Calcutta’s Albert Hall, where Indians of all faiths, Hindus, Muslims and Christians, gathered to pay tribute to this remarkable woman. This commemorative meeting was chaired by Rokeya’s longtime friend Mrs P.K. Roy, who in her presidential address made the following remarks about Rokeya and her cross-border cultural outlook (Sufi, 2001: 33, my translation):

The more I saw her, the more I was impressed by her broad outlook. She knew that mere customs and rituals couldn’t make a true faith; that which can elevate the human condition to a higher level, was the only true and lasting religion.

I loved her, because I shared her dreams and aspirations. She knew no difference between Hindus and Muslims; neither do I.

I always revered her, because she embodied the image of a true Indian woman in every sense—whatever that is truly India, is what she cultivated all her life.

Rokeya cultivated Indic values throughout her life. She considered herself first and foremost an Indian national. Thus, in her essay ‘Sugrihini’ (‘The Good Housewife’), she stated unequivocally that it was important for all Indians to place their national identity over and above their religious and regional identities, in order to heal all differences between those of different ethnic and religious backgrounds and bring the country together. She wrote (Quadir, 2006: 56; my translation):

We ought to remember that we are not merely Hindus or Muslims; Parsis or Christians; Bengalis, Madrasis, Marwaris or Punjabis; we are all Indians. We are first Indians, and Muslims or Sikhs afterwards. A good housewife will cultivate this truth in her family. This will gradually eradicate narrow selfishness, hatred and prejudice and turn her home into a shrine; help the members of her family to grow spiritually.

As Mrs P.K. Roy said in her eulogy, Rokeya also believed that all religions were in essence one, as the objectives of all religions were to elevate the human condition and to establish harmony in society. Explaining this non-sectarian,inclusivist and sublime outlook, Rokeya wrote in the dedicatory note to her novel Padmarag (‘Ruby’), by drawing an anecdotal example from her elder brother, Ibrahim Saber (taken from Quadir, 2006: 263, my translation).:

A religious person once went to a dervish to learn about meditation. The dervish said: ‘Come, I’ll take you to my guru’. This guru who was a Hindu, said: ‘What will I teach? Come, I’ll take you to my guru’. His guru was, again, a Muslim dervish. When the disciple asked the dervish about this free mingling among the Hindu and Muslim priests, the dervish replied: ‘Religion is like a three-storied building. In the lowest floor there are many quarters for Brahmins, Kshatriyas and other castes among Hindus; Shi’ites, Sunnis, Shafis, Hanafis and other sects among Muslims; and, likewise, for Roman Catholics, Protestants etc. among Christians. If you come to the second floor, you will find all the Muslims in one room, all the Hindus in one room, etc. When you reach the third floor, you will notice there is only one room; there is no religious segregation on this floor; everyone belongs to the same human community and worships one God. In a sense no differences exist here, and everything dwells in one Allah only’.

Perhaps it is in keeping with this outlook that Rokeya also read Hindu scriptures. There is evidence in her work of a familiarity with the Ramayana, the Upanishads, the Vedas and the Bhagavad Gita. In her essay, ‘The Female-half’ (‘Ardhangi’), for example, she mentions the story of Rama and Sita, though she rejects the story’s premise of being a positive example of familial relationship between husband and wife, considering Sita too slavish and submissive, and Rama overly insensitive and domineering. In ‘Educational Ideals for the Modern Indian Girl’, however, Rokeya cites the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita approvingly, arguing that it is important for all Indians, despite their respective religions, to be aware of the Indian heritage of education and to assimilate the old while holding to the new.13 Rokeya also explains that Indian education was religious at the beginning, as its primary objective was to train young Brahmins for their duties in life as priests and teachers of others (Hasan, 2008: 504). As a result, there has always been a moral dimension to the Indian education system. As India modernises appropriating the Western utilitarian mode of education, it should not rid itself of these Indian values, which give a distinctive quality to its education system. It should rather adjust and amplify those values to suit the modern context, to avoid what Rokeya refers to as ‘a tendency to slavish imitations of Western custom and tradition’ (Hasan, 2008: 505). The need is to be modern and yet Indian at the same time, as Rokeya (Hasan, 2008: 506) proffers:

India must retain the elements of good in her age old traditions of thought and methods. It must retain her social inheritance of ideas and emotions, while at the same time by incorporating that which is useful from the West a new educational practice and tradition may be evolved which will transcend both that of the East and the West. .

Rokeya also shows familiarity with Hindu myths and Puranic tales. She mentions Durga, Kali, Shitala and other Hindu goddesses in her work. Two of her essays, ‘The Creation of Woman’ (‘Nari-srishti’) and ‘The Theory of Creation’ (‘Srishti tawtho’) are built on the Hindu Puranic tale of Tvastri’s creation of the universe, in particular the creation of man and woman. The latter essay has Hindu and Muslim characters–Jaheda Begum, Shirin Begum, Nonibala Dutta and Binapani Ghosh– living under one roof, or at least spending the night together as friends. In ‘Nurse Nelly’, again, we are told that the narrator, Jobeda, has a good friend, Bimala Devi, a Hindu woman, whom she visits at the hospital every day when she goes to Lucknow with Khuki, her younger sister-in-law, for the latter’s treatment.

In her essay ‘Home’ (‘Griha’), Rokeya gives examples from both Hindu and Muslim societies to show that all women in India are essentially homeless, owing to the fact that no matter what caste, class or religion they belong to, they all have to live at the whim and mercy of men.

In ‘Woman Worship’ (‘Nari Puja’), Rokeya has four women conversing on the purdah system, two Muslims and two Hindus: Mrs Chatterjee, Kusum Kumari, Amena and Jamila. The women discuss how the purdah practice has plagued women for centuries in both religious communities, giving examples from both to show that men have treated women like animals, sometimes even worse than animals. When Mrs Chatterjee naïvely suggests that women enjoy deified the status in Hindu society, Amena retorts, in effect summing up the author’s view: ‘Excuse me…. the position of woman in this country is no better than a slave’s’ (Quadir, 2006: 196, my translation).

In The Zenana Women (Aborodhbashini), again Rokeya draws examples from both Hindu and Muslim communities to illustrate how women in India have been dehumanised and commodified by a patriarchal system that has spread its roots through all Indian religious traditions. Thus, if Muslim women have to live a mute, abased, obedient and invisible life, with no control over their minds and bodies, remaining utterly dependent on their male counterparts for every business of life, this is the condition of Hindu women too, who are equally deprived of their selfhood and dignity. Forced to live an often abject and ignoble life, they exist totally at the caprice and clemency of their men.

The book has 47 episodes. In most of these Rokeya ridicules the excesses of the purdah practice in Bengali and Bihari Muslim communities that deprived women of life’s opportunities: education, personal and social freedom, as well as rights to work, wealth and inheritance. However, in two episodes (episodes 12 and 41) Rokeya specifically empathizes with Hindu women. The first of these episodes takes a swipe at the practices of child marriage and female segregation simultaneously, depicting a child bride who goes for a holy bath at the Ganges with her family, gets lost in the crowd and starts following another man only because the man is wearing clothes of the same colour as her husband’s. Asked why she was following the other man, the girl innocuously explains that since ‘she always covered her head with a veil, she had never seen the face of her husband fully before’ (Quadir, 2006: 389, my translation).

In the second episode, Rokeya recounts two incidents from Shrijukta Rai Bahadur Jaladhar Sen’s recollection from his youth of ‘stringent and even laughable purdah practice.’ The first one is about ‘a mosquito net travelling’, the second about ‘a palanquin bathing’. In the first incident Jaladhar Sen recollects how he saw a woman entering Howrah station to board a train one day, covered in a mosquito net. He found the incident so ridiculous that he could not contain himself, commenting: ‘I…could not restrain my laughter at the sight of that ostentatious display of purdah. Oh, yes, this is the true purdah—nothing short of an expedition in a mosquito net’ (Quadir, 2006: 407, my translation). The second incident narrates the sight of a Hindu woman brought to the Ganges river banks for a holy bath. The woman is not allowed to step out to bathe; instead the palanquin with her inside is dipped into the water by the bearers. She is later carried back home in that wet condition. Apparently, the woman is not let out because her family honour would be compromised if her face were visible to strangers. Both Hindu and Muslim women are treated like precious commodities to be jealously guarded by men, invisible to the rest of the world, stripped of their agency and individuality altogether.

In ‘The Mysteries of Love’ (‘Prem-rahasho’), an autobiographical story, Rokeya declares: ‘I have loved people of all religions—Hindu, Christian, Muslim, but why, I am not sure of it myself’ (Quadir, 2006: 429, my translation). Love, she argues, is mysterious; it defies all logic and social norms. Although human nature is to instinctively love something attractive and beautiful, sometimes things not so beautiful can also fascinate us. Love cannot be circumscribed or compartmentalised on the basis of race, language or creed. It transcends all borders. We are capable of loving another human being regardless of cultural or religious identity, age, class or caste.

Rokeya narrates three experiences of ‘sisterhood’ from her own life as illustrative of this transcendental experience. Her ‘love’ relationship with Champa, an untouchable girl in Orissa; with Ms. D, an English woman; and with an elderly woman from northern India, whom she describes as ‘my patient’. The story documents how each of them came close to the narrator and meant so much to her, though Champa and Ms D were from different cultural-religious groups, and the elderly woman came from a different language and age group. Rokeya not only advocated cross-cultural unity and inclusivity in her writings, but also experienced and practiced them in her personal life.

Starting out from totally different perspectives Tagore and Rokeya, shared a dialogic spirit and sought to bring together Hindus and Muslims in their work. Though they largely focused on the follies and foibles of their own cultures, hoping to help their respective communities ride above such weaknesses and move forward, they consistently advocated fellowship between various cultural and religious groups, especially between the two largest religious communities in the country, Hindus and Muslims.

Tagore and Rokeya’s message of peace, amity and unity has lost none of its relevance and poignancy in Hindu-dominated India and Muslim-dominated Bangladesh, in particular. ,

*******

References

Ahmed, Rafiuddin (2001) ‘The Emergence of the Bengali Muslims’. In Rafiuddin Ahmed (Ed.), Understanding the Bengali Muslims: Interpretative Essays (pp. 1–25). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Das, Sisir Kumar (1996) The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore: A Miscellany. Vol. 3. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

Datta, Pradip Kumar (2012) ‘Women, Abductions and Religious Identities in Colonial Bengal’. In Charu Gupta (Ed.), Gendering Colonial India: Reforms, Print, Caste and Communalism NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE (pp. 265–86). Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan.

Desai, Anita (1985 [1915]) ‘Introduction’. In Rabindranath Tagore, The Home and the World (tr. Surendranath Tagore) (pp. 1–7). London: Penguin.

Dutta, Krishna & Robinson, Andrew (1997) Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hasan, Morshed Shafiul (2008) Rokeya Rachanabali. Dhaka: Uttran.

Hossain, Yasmin (1992) ‘The Begum’s Dream: Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and the Broadening of Muslim Women’s Aspirations in Bengal’, South Asia Research, 12(1): 1–19. Karim, Maulvi Abdul (1935) A Simple Guide to Islam’s Contribution to Science and Civilisation. Calcutta: Goodword Books.

Kripalani, Krishna (1962) Rabindranath Tagore: A Biography. London: Oxford University Press. Mahmud, Shamsun Nahar (2009 [1937]) Rokeya Jibani (The Life of Rokeya). Dhaka: Shahitya Prakash.

Novak, James J. (2008 (1994) Bangladesh: Reflections on the Water. Dhaka: The University Press Ltd.

Quadir, Abdul (2006) Rokeya Rachanabali (Collected Works of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain). Dhaka: Bangla Academy.

Quayum, Mohammad A. (2004) ‘Rabindranath Tagore and Nationalism’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 39(2): 1–6.

——— (2006) ‘Imagining “One World”: Rabindranath Tagore’s Critique of Nationalism’, Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, 7(2): 20–40.

——— (tr.) (2011) Rabindranath Tagore: Selected Short Stories. New Delhi: Macmillan. ——— (2012) ‘Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’. In Robert Clark, Emory Elliott & Janet Todd (Eds), The Literary Encyclopedia. London: The Literary Dictionary Company. URL (consulted 25 March 2013), from http://litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=13179. Radice, William (tr.) (2005) Rabindranath Tagore: Selected Short Stories. London, New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Ray, Bharati Ray (2002) Early Feminists of Colonial India: Sarala Devi Chaudhurani and Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sufi, Motahar Hossain (2001) Begum Rokeya: Jiban O Shahitya (Begum Rokeya: Life and Works). Dhaka: Subarna.

Tagore, Rabindranath (tr.) (1915) One Hundred Poems of Kabir. London: Macmillan. ——— (2008) Galpaguccha (Collected Short Stories). Kolkata: Visva-Bharati.

———————-

The above is a shortened edited version of the original that appeared under the title: HINDU–MUSLIM RELATIONS IN THE WORK OF RABINDRANATH TAGORE AND ROKEYA SAKHAWAT HOSSAIN in South Asia Research Vol 35(2): 177-194.

With kind permission of the author.

———————-

Mohammad A. Quayum is a faculty member at College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide. He is the author of Beyond Boundaries: Critical Essays on Rabindranath Tagore (Bangla Academy, 2014) editor of The Poet and His World (Orient Longman, 2011) and Tagore, Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism (Routledge, 2020).

Leave a Reply