Ashwin Desai

“Where no monuments exist to heroes but in the common words and deeds . . .” Walt Whitman

N

ovember 16th marks the 160th anniversary since the first Indian indentured labourers arrived at Port Natal. Like Shiva’s dance it is a journey without end.

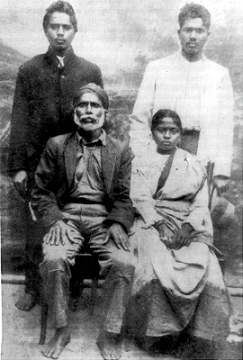

None more so than the Munigadu family of Rangadoo indentured number 57684 and his children Narainsamy, Amasigadu and Muthialu. They made contact with the South African government from Dar-es-Salaam on 14 April 1922 when Munigadu was seeking re-entry into South Africa. Their ‘contact’ with South Africa had begun much earlier. Munigadu was 21 when he first arrived in Natal from north Arcot on the Congella in March 1895. He was assigned to the Natal Central Sugar Company in Mount Edgecombe. A shipmate, Mangai was assigned to the same employer and they married shortly after. Mangai died in 1904 soon after and Munigadu married Thayi Chinna Kistadoo.

When Thayi died, the family returned to India with their father on the Umhloti on 26 August 1920 under repatriation. After Thayi’s death, Munigadu needed ‘consoling’ and sought solace from his extended family in India but found India to be ‘almost a foreign country’. They could not return to ‘the land of birth’ because Munigadu had abandoned his and his family’s right to domicile in South Africa. They were desperate to escape India and made their way to Dar-es-Salaam and from there sought permission to enter South Africa. When this was refused, they walked through present-day Mozambique to northern Zululand, where they were apprehended.

They walked over 2 000 miles in ‘some of the most difficult country in the world with no little danger from wild animals’. The Principal Immigration Officer in Durban, GW Dick, declined their request to remain in South Africa even though Advocate Leon Renaud wrote to him on 15 May 1923:

The Appellants were born in this country. Under the influence of their father they consented to undertake not to return again to Natal….They went to India and found that their father’s relations had died or disappeared and the country was a place distant and foreign to them in every way. The land was new, even the air that they breathed was foreign to them. They lost heart and endeavoured to trace their steps to this country.

Dick advised the government to deport them ‘on principle’. The government declined Munigadu’s application. To complicate matters, Renaud informed Dick on 19 June that the son, Muthialu had married a Natal-born Indian, Marimuthu, in Zanzibar. Since Marimuthu had the right to domicile in South Africa, as much as Dick hated the idea, he could not deport Muthialu. Munigadu challenged the deportation order but his application was dismissed and he was deported in early October 1923.

Narainsamy and Amasigadu appealed their deportation on 6 October 1923, but lost their case. The brothers were deported on the Karagola on 10 December 1923. Muthialu would never see her brothers and father again, with whom she had braved a walk of 2000 miles.

The Munshis were more fortunate than Munigadu’s family, though it did not seem so for a long time. On 13 May 1927, seventeen-year old A.M. Munshi wrote to the Governor-General of South Africa from Bombay for a “free pass” to return to South Africa. The family, made up of his father, mother, three brothers, and a sister, had returned to India in 1924. All the children were born in South Africa. Between 1924 and 1927, two brothers died of poverty:

We are born under the British flag and we claim our British right. For the last three years had we been in starvation… Here we have lost two of our brothers and the rest are daily sick. My parents are very old. Here we have nobody to our care …We are asking in the name of God for a pass to our Longing Land…

H.L. Smith, the Governor-General’s secretary, acknowledged the letter but did not follow-up. Munshi wrote again on 3 August 1927, once more signing the letter “The African Family”.

The family tried year after year without success. Eventually, on 10 October 1936, the mother, appealed to the Governor-General:

For twelve weary years have I written dozens of petitions to the Governments to send me back to my Native Land. Your Excellency, what have I and my children done that we can’t be permitted to return to our Native land? What crime have we committed to be deported to a foreign land?

In October 1938, Mrs. Munshi finally received passports, dated 2 May 1938, for two of her sons.

**

Fast forward to the present day. There are those who insist on spending millions of rands on a monument to indenture. It’s understandable that they want history to be recognised. Should it be a cane-cutter? A coal-miner or railway worker? And if it is a family, will that not write the single woman who came out of herstory? Again. What about the gay and the cross-dressing migrant? This single image captured in a monument reinforces Pierre Nora’s point that as ‘memory remembers…history forgets’. Monuments freeze. Yet as Chamoiseau and Glissant remind us ‘The same skin can have different imaginations. Similar imaginations can have different skins, languages and gods’.

After 160 years, surely it is time to confront the straitjacket that goes under the label Indian. A label that the Munigadus and Munshis challenged nearly a century ago. When will we insist on our African heritage by at least debating the identity, Afro-Indian? Maybe there should be no hyphen, allowing the words to merge, confronting the idea, as Paul Gilroy put it, that there is a ‘single culture…hermetically sealed off from others; Culture, even the culture which defines the groups we know as races, is never fixed, finished or final.’ Some might argue that we should just have the label South African, others that we should hark back to the time of Steve Biko’s innovation of Blackness. Identities though are not a tabula rasa that one can just willy-nilly write upon. At the same time however, and to steal from Virginia Woolf’s words on books; identities ‘have a great deal in common; they always overflow their boundaries; they always breed new species from unexpected materials’.

AfroIndian gestures to not only who we are but that we are always in the process of (un)becoming. A bunny chow if you like.

Now here’s an idea. A monumental bunny chow overlooking Blue Lagoon. The place where many streams join the Umgeni in a dash to the Indian Ocean.

Bunny Chow. The most South African of dishes, born at the height of colonialism’s barbarism. It says a lot that a Kota is an imitation.

Open the door of a half loaf, to a living (anti) colonial museum that talks to the past and the future. To give a snippet, think of the life of King Dinuzulu, who linked up in July 1884 with a hundred mounted Boers to defeat the British imposed Chief Zibhebhu. Boer and Zulu riding side by side across a river whose blood still flowed. Subsequently, Dinuzulu was found guilty of high treason and exiled to St. Helena. Dinuzulu was released in 1898 only to suffer four years’ imprisonment after the Bambatha Rebellion. When General Louis Botha became Prime Minister of South Africa in 1910, one of his first acts was to order Dinuzulu’s release. He granted him a farm near Middelburg, Transvaal, He died in 1913, the year of the Indian indentured’s great strike. On the upper reaches of the bunny chow, the names of every one of the 152 184 indentured. On a wall the story of the Old Natal British settlers many of whom are not what they seem as they manufactured a double-barrelled surname. The Green became the Lovell-Greens, the common-as-smallpox O’Farrell’s lost the O’ on the ship over to Port Natal to occlude their Irish origins.

Contra to those who today seek to write our histories in Black and White, there are many shades of Brown, many myths dressed up as iron, in this special type of KwaZulu-Natal colonialism. Ask the children of the White Zulu Chiefs appointed by Shaka.

To try and force a single-rootedness is to fly against history. Ask Kamala Harris about single roots. Through three centuries in Africa, while not exactly an immaculate conception, something new, made in Africa continues to mutate.

Imagine this mix and flow under the protective gaze of an up-to-date potato, gravy overflowing, refusing to be boxed in. As Edouard Glissant evocatively points out ‘we each need a memory of the other…if we want to share in the beauty of the world, if we want to show solidarity…we have to learn to remember together’. He should have added that we have to also learn to eat together.

A Bunny Chow museum.

A place where everyone can munch on a piece of history and where in Wole Soyinka’s words we can ‘leave the dead…room to dance’.

*******

Note. Bunny chow, often referred to simply as a bunny, is a South African fast food dish consisting of a hollowed-out loaf of white bread filled with curry. It originated among Indian South Africans of Durban. A small version of the bunny chow that uses only a quarter loaf of bread is sometimes called, by black South Africans, a scambane or kota ("quarter"); it is a name that it shares with spatlo, a South African dish that evolved from the bunny chow.--Wikipedia

'Ashwin Desai is Professor of Sociology at the University of Johannesburg and author of Reverse Sweep: A Story of South African Cricket Since Apartheid.' More by Ashwin Desai in The Beacon Ways of (not) Seeing: Cricket and its Discontents When Cricket’s not Cricket: When Shame’s in Short Supply Pandemic Musings from South Africa

Leave a Reply