Prelude

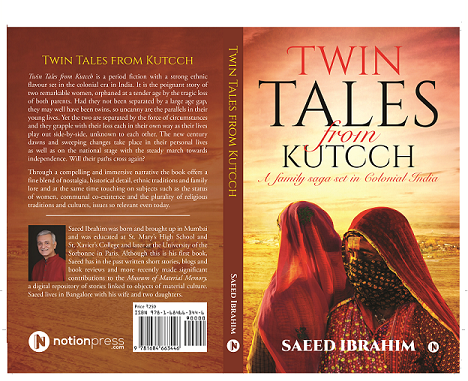

“Twin Tales from Kutcch” is a family saga set in the Colonial period in India. It is a story of how two women, the author’s respective grandmothers, are orphaned at an early age, grapple with their loss, each in their own way and unbeknownst to each other, as sweeping changes take place in their personal lives, as well as on the national stage. The book covers the period from the closing years of the nineteenth century (an era of horse drawn carriages, gas-lit street lamps and steamship travel) to the period just before independence..

The extract below lays out the backdrop to one of the two historically documented events that were crucial to the narrative of the author’s paternal grandmother who was to be orphaned in her teens. This was the maritime tragedy of 8th November 1888 which came to be known in later years as the “Titanic of Gujarat,” although in actual fact the RMS Titanic sank 24 years later in April 1912. The SS Vaitarna (nicknamed “Vijli” or electricity) on her maiden voyage from Bhuj to Bombay, sank and disappeared mysteriously off the coast of Gujarat. Ibrahim’s great grandparents who lived in Bhuj (the capital of the erstwhile semi-autonomous princely state of Kutcch in Gujarat) were travelling on the ship and they both met a tragic end when the ship was wrecked after a violent cyclonic storm, leaving no survivors.

![]()

This extract from the first few chapters of the book describes in dramatic detail the tragic sinking of the SS Vaitarna. But before that denouement, the reader gets acquainted with subtle threads weaving the quotidian lives of the characters: harmonious communal co-existence; plurality of social and religious traditions, evident too in food and clothing and marriage customs. The Beacon

***

Saeed Ibrahim

J

an Mohammed sat in his favourite easy chair on the wide verandah of his comfortable four room bungalow with a copy of the Gujarati newspaper the Bombay Samachar spread out in front of him. Although since 1855 the newspaper had graduated from a bi-weekly to a daily, it took days before his copy reached him in Bhuj. By then the news was already a bit out-dated, but Jan Mohammed eagerly awaited the delivery of his newspaper as it helped him keep abreast of events in Bombay (now known as Mumbai) and the happenings in the business community there. This day in May 1888 he read about the completion of Bombay’s Victoria Terminus, that architectural marvel in the Indo-Saracenic style designed by the British architect Frederick William Stevens to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria who had completed fifty years as a monarch. He remembered how the work on the new railway station had started a decade earlier in 1878 on the site of the old Bori Bunder station from where on the 16th April 1853, the Great Indian Peninsula Railway had operated the first passenger train from Bori Bunder to Thana covering a distance of 39 km and heralding the birth of the Indian Railways.

But now his musings about the new Victoria Terminus were interrupted by the arrival of Imtiaz, the local barber who came to the house twice a week to give Jan Mohammed his customary shave and beard trim. After meticulously finishing the task at hand, Imtiaz ingratiatingly held up a hand mirror before his client’s face to seek his approval. Jan Mohammed looked up to see his image reflected in the mirror. At 48, his face with its wide set eyes, straight nose and broad forehead was still handsome and unlined, although the hair on his head and his beard had a generous sprinkling of grey, which, according to some, gave him a more dignified appearance.

To Imtiaz he gave a curt nod of his head to indicate his satisfaction. It always helped to keep Imtiaz in check because he was the town’s gossip monger and loved chatting up his clients in between cutting their hair or shaving their beards. But at Jan Mohammed’s house he knew better and always remained uncharacteristically tight lipped. Jan Mohammed reached into his pocket and paid Imtiaz his dues and thought reminiscently of the story his father would tell the children to illustrate how barbers had always been known for their indiscretion and their inability to keep a secret.

His father, who always loved an audience, would clear his throat and start:

“In the old days, the town barber would not be paid for his services in cash, but rather in kind– a bag of grain or a seer of oil and often, if there was a marriage in the family, a brand-new item of clothing, invariably, a sherwani. Thus, the barber’s wardrobe was always well stocked and he was never short of clothes. Now it so happened, (his father would continue), that a friend of the barber’s was getting married but did not have a sherwani to wear for the occasion.

‘Why do you worry my friend, I have a yet unused sherwani at home and I would be happy to loan it to you and get you out of your predicament,’ the barber offered. The groom was overjoyed and gladly accepted the generosity of his friend. Now as they stood outside to welcome the guests, both attired in shining new sherwanis, the barber piped up:

‘Welcome, welcome, do come in. But make no mistake. My friend here is the groom, but the sherwani is mine.’

The groom went scarlet with embarrassment and quietly whispered to the barber, ‘Why did you have to say anything about the sherwani?’

‘I am sorry’, countered the barber, ‘I will not say anything next time.’

But unable to keep the matter under his hat, when the next lot of guests passed by, he exclaimed,

‘This here is the groom, and the sherwani is also his.’

The groom now was beginning to get angry at his friend’s indiscretion and remonstrated again with him. His friend with profuse apologies promised that he would no longer say anything. However, unable to contain himself, as the last lot of guests trooped in, he blurted out,

‘Here is the groom, and of course there can be no mention of the sherwani,’” Jan Mohammed’s father would end dramatically amidst peals of laughter.

Smiling to himself at the memory of this amusing story, Jan Mohammed stepped into the house to check with his wife Hajra if she had kept his bath water ready. Knowing that her husband liked his bath water plentiful and hot, Hajra had earlier made sure that Sakina, her house help had topped up the water and installed hot burning coals in the large bronze samovar in the bathroom.

Jan Mohammed stepped out of his bath and began getting dressed, putting on a pair of starched white pyjamas tapered at the ankles and a long knee-length white kurta topped by a short, buttoned-up waistcoat. Summers in Bhuj were extremely hot and he wore his sherwani and red tasselled fez cap only for more formal occasions.

“Breakfast is ready Sait”, Hajra called out in Kutcchi, the language they spoke between themselves. It was not the custom for good Kutcchi wives to address their husbands by their first names and Hajra used the more respectful “Sait” whilst addressing her husband. They both were also conversant in Gujarati and Urdu, and Jan Mohammed in English as well, although Gujarati was the language in which all local business was conducted. The couple now sat down to a breakfast of sevian topped with sugar, warm milk and thick fresh cream and crisp, deep fried pakwan, enjoyed plain or dunked into hot cardamom – flavoured tea.

But the house seemed somehow empty without Aisha, their demure and mild-mannered sixteen-year-old daughter. Aisha’s clear and unblemished olive skin and large brown eyes made her a pretty and poised young lady, but unlike her mother’s exuberance and robust good health, she had a more delicate physique and a shy, retiring nature.

Hajra’s older sister Halima was married to Rehman, Jan Mohammed’s cousin and they had settled in Bombay. They had two daughters only a few years older than Aisha and on their last trip to Bombay Hajra had been persuaded by her sister to allow Aisha to stay back. Being an only child, she was often lonely back home in Bhuj and the company of her cousins and the boisterous air of Halima’s household in Bombay would do her good according to her aunt. Besides, she reasoned, Jan Mohammed could easily take her back on his next trip to Bombay which he made at least twice a year combining both business and a family visit.

Hajra had appeared convinced and had agreed to the proposal, but now barely a month down the line she was already missing her daughter and had begun to have second thoughts about her decision to leave her back in Bombay. Little did Hajra know at the time, how inexorably her decision was to affect the future course of events in their lives.

xxxx

As with the other Kutcchi Memon families living in Bhuj, Jan Mohammed and Hajra were descended from the Lohana Memon families living in Thatta in Sindh who had converted to Islam in the 15th century A.D. and subsequently left Thatta and migrated to Gujarat. They had come to be known as “Momins” or believers. The word “Momin” was corrupted later on to “Memon”. Some families travelled to Bhuj and decided to settle down there. This group of Memons came to be known as Kutcchi Memons. From 1813 or 1816 onwards some Kutcchi Memons started moving out of Bhuj, seeking their fortune in other cities in India and overseas, but notably Bombay, attracted by its business opportunities.

From his Kutcchi Memon ancestry, Jan Mohammed had inherited a strong business acumen coupled with qualities of honesty, integrity and generosity, qualities that had gained for him the respect and goodwill of other members of Bhuj society, and in particular the trust and affection of his Parsee business partner, Jamshedji Khersetji Madon. Together they had set up “Jan & Co.” a thriving silver ware and crockery outlet located in the Camp area of Bhuj.

The Camp area of Bhuj was an area located beyond the old walled city and at the foot of the Bhujia Hill. This was the area where in 1819, the British forces had set up “camp” after capturing the hill fort of Bhujia and establishing their authority over the area, which until then had been part of the independent princely state of Kutcch. The area had since become known as the Camp area and by the latter part of the 19th century, the Camp area of Bhuj had become a prosperous and almost exclusive quarter inhabited by the British officers and their households and some of the more affluent and influential Indian families.

It was just before 10 o’clock each morning that Jan Mohammed set out in his horse-drawn buggy to join his partner at the shop. Hajra on the other hand, having seen off her husband, would continue with the rest of her morning routine, supervising Sakina as she got her to dust and clean the house and wash the clothes and help Hajra in the kitchen with the preparation of meals.

At 40, Hajra was an energetic and organized housekeeper and a good cook. Her biryanis, fish curries, khitchda and muthias were well known amongst community and friends. She was particular about the right ingredients and would never proceed with making a dish unless all the required items were at hand. Surprisingly though, despite her bustling energy and culinary talents, Hajra lacked self-confidence. She had a nervous and superstitious nature. Unsure of herself, a constant worrier prone to bouts of anxiety and self-doubt, she always relied on the validation and support of those around her. But right now, time was rushing ahead and Hajra had to press on with getting the afternoon lunch ready and packed. Abdul, the young assistant from the shop would soon be there to pick up Jan Mohammed’s lunch after which he would stop by at the other partner’s home where he would collect a similar tiffin box with Jamshedji’s lunch.

Jamshedji and his wife Mehroo, along with about twenty-five Parsee families, lived in the Camp area of Bhuj, not far from the premises occupied by Jan & Co. Their home was a good-sized bungalow with five rooms surrounded by a large balcony in the front as well as on both sides of the house. It was tastefully decorated with a carved wooden screen in the large central hall running the length of the bungalow and separating the sitting room area from the dining room behind it.

One wall of the sitting room was covered with a large tapestry depicting a pastoral scene from the English countryside whilst the opposite wall had a large portrait of Queen Victoria occupying pride of place in the centre and surrounded by family photographs on either side. Below the portrait was a showcase with several porcelain and lace figurines from Dresden and on the opposite side a comfortable sofa and chairs with antimacassars covering the arms and headrests. The coffee table in the centre and small teapoys placed between the sofa and chairs had dainty and quaint looking lace doilies. In the far corner of the sitting room was a Steinway piano and the well-worn sheet music was proof that the piano was being played regularly by one or other family member, in this case, Jamshedji’s wife Mehroo.

Mehroo was a tall and slim woman in her mid-thirties, always elegantly turned out in pretty dresses or traditional Parsee style sarees as the occasion demanded. She was fond of jewellery and matching accessories and fine perfumes and whenever she passed by a room she left behind the lasting aroma of her sweet presence.

Jamshedji on the other hand was the exact physical opposite of his wife. Portly, with a slightly protruding belly for one who was just forty years of age, he had a clean-shaven and cherubic looking pink complexion. Good natured and with a ready smile, he had an impish sense of humour with which he chaffed his friends and those close to him. A bon vivant who loved good food and the finer things in life, he had a gramophone and an enviable collection of western classical music records and never missed his glass of port wine after a good dinner.

Unlike her husband’s warm and engaging personality, Mehroo on the other hand was a bit aloof and not easily approachable. This tendency on her part did not make things easy for the self-conscious Hajra and the two women had not been able to establish the kind of friendly bond that their husbands enjoyed.

At 10 AM sharp, Jan Mohammed arrived at the shop to find Abdul the shop assistant waiting for him at the doorstep. Whichever of the two partners arrived at the store first, it was up to him to open shop. Today Jan Mohammed having arrived first, had scored over Jamshedji and he pulled out a large iron key ring from which dangled three long keys. He handed the key ring to Abdul who bent down to open the two massive pad locks on either side of a steel roller shutter. Having opened the two pad locks and relocked them in their respective hooks, Abdul lifted the handle of the shutter upwards and it went up with a loud fluttering sound revealing a thick wooden entrance door and two glass shop windows on either side.

The two decorated windows at Jan & Co. were a beholders delight. The window on the right had a blue and white willow pattern Staffordshire dinner set with its oblong platters, serving bowls, soup bowls and dinner plates tastefully arranged and displayed. The left-hand side window had an exquisite Aynsley tea set in pure white with pink roses and green leaf borders, with unusually shaped tea cups and pretty handles. Abdul turned the key and pushed open the entrance door and the two of them entered the shop to be greeted from behind by a resounding “Good morning, Jan. I see that you have beaten me to it today.” Jan Mohammed accepted the compliment from his jolly-natured partner and they both settled down to the day’s business.

There were the usual requests for table ware and cutlery from the officers’ mess, from the home of the British Resident or from the houses of the affluent and more westernized sections of Indian society. But today was a particularly busy day, with the visit of Mr. Stevens the majordomo from the Prag Mahal Palace.

The Prag Mahal Palace was the Bhuj residence of the Maharao of Kutcch, his highness Khengarji III of the Jadeja Rajput Dynasty which ruled the princely state of Kutcch from 1540 to 1948. The palace was designed in the Italian Gothic Style and was made of Italian marble and sandstone from Rajasthan with a 45-foot-high clock tower from where one could get a view of the entire Bhuj city.

![]()

The palace had been commissioned in 1865 by the previous ruler, Rao Pragmalji II who had died in 1875 before the completion of the palace. Construction was completed only in1879 during the regency of his son Khengarji III who had succeeded him on his death. A few months after reaching majority, he had been invested with full ruling powers on 14th November 1884 and in the following years he had become a popular ruler both amongst his own people as well as amongst the ruling elite in Delhi and London.

For Jan & Co. Mr. Stevens had placed a special and very large order of bone china crockery, porcelain dinnerware and decorative silverware for at the palace, hectic preparations were underway for the forthcoming birthday of his highness. A grand banquet was being planned to celebrate his 22nd birthday and visiting dignitaries from far and wide were expected at the palace to honour the young Maharao.

xxxx

Not surprisingly, the monsoon in Bhuj that year had been scant and unpredictable and July and August had been sweltering. With the hot, semi-arid almost dessert like climate, conditions in the old walled city with its small, narrow and winding streets could often be suffocating. Bare-chested artisans worked under such torrid conditions in tiny workshops making ajrakh shawls and quilts, mirror work textiles, lacquered pottery, wooden decorative carvings, or silver and gold beaten sheets for filigree and zari embroidery. The city walls and the city gates had been repeatedly damaged and rebuilt after the 1819 earthquake and evidence of the patchwork reconstruction could be seen all around.

Kanti Desai, who worked as the accountant and bookkeeper at Jan & Co, lived in the old walled city. Whereas most of the houses here were single storey stone structures, Kanti’s house was a handsome, double storey building made of heavy timber with an ornate and artistic doorway which made his home stand out from amongst its neighbours in the main vegetable market area in the heart of the old city.

Kanti Desai would leave home early on foot in order to be in time at the shop since both Jan Mohammed and Jamshedji were sticklers for punctuality. However, Kanti was a dedicated and gifted accountant and a wizard with figures and the partners often turned the Nelson’s eye when he occasionally arrived late. Jan Mohammed in fact was particularly indulgent with Kanti because in his father’s tradition he was always game for an amusing story and Kanti had a stock of funny anecdotes which he would sometimes dare to relate in front of his bosses if he found them in a good mood. Today seemed to be a good day because business had been thriving and the atmosphere prevailing at the shop was jovial and light-hearted.

The buoyant mood in Jan Mohammed’s household was further enhanced by the news from Bombay. The parents had learnt from a letter they had received the previous week that Aisha was happy and comfortable in Bombay and had been enjoying her stay there, attending community functions and events in the company of her aunt. Hajra began to wonder if her apprehensions about leaving Aisha behind in Bombay had after all been unwarranted, until an incident occurred the following month that brought back her anxiety, gave her sleepless nights and destroyed her peace of mind.

On a Thursday afternoon in October, Hajra was readying herself for an engagement ceremony she had to attend at the home of a friend. Kutcchi Memon alliances usually began with a bit of matchmaking done by the elders of the community and culminated by a formal proposal from the boy’s side. The male family members from both sides would then meet between themselves to formalize and seal the engagement and sweet refreshments would be passed around. This was followed by an exclusive ladies event called a bolani where the young bride to be was given a gift of clothing and jewellery from the boy’s side including sometimes an engagement ring. With Kutcchi Memons, engagements and marriages tended to be endogamous, within the same community or group with common social values and customs.

As she began getting dressed, Hajra’s thoughts automatically drifted towards her own daughter. The time was now ripe when she and Jan Mohammed would have to start thinking of a suitable match for Aisha. How and when this would occur she believed would have to be left in God’s hands. But she knew that as parents they would have to in some manner initiate the process. Dressed in the traditional long ankle length gown and pyjamas with embroidered bottoms and a bandhni odhni, Hajra nonetheless had to cover herself fully with her heavy gold embroidered milaya and missar scarf before she could step out of the house and walk the short distance to the home of her friend.

She was about to step out of the house when she heard a loud cry emanating from outside the verandah steps.

“Bibi, Allah ke naam par kuch dedo”. (Lady, give alms. God will bless you.)

The voice came from a mendicant fakir who would come by erratically now and then but particularly on Thursdays to seek food and alms. He had a flowing white beard and kohl darkened eyelids and was dressed in a long loose fitting black abaya and a green turban with several layers of beads strung around his neck. He wore copious silver rings capped with coloured stones on the fingers of both hands. In one hand he held a long tasbih and in the other a deep begging bowl.

Hajra was used to his occasional presence by her verandah steps and would often ask Aisha to fetch food from the kitchen and put it out onto his begging bowl. This along with a small donation in cash was readily accepted and would be followed by a long litany of blessings for the health and happiness of all the family members. This Thursday was no exception and Hajra herself doled out the food and alms. The fakir, noticing the absence of Aisha, asked after her and being told she was away, exclaimed “Go to her now Bibi, or you will never see her again.” With this he turned around and disappeared, leaving Hajra dumbfounded and stunned.

Horrified by the Fakir’s ominous prediction, Hajra slumped down into the nearest chair. A cold shiver ran down her back and she sat motionless staring blankly at the empty space in front of her. What had he meant when he said that they would never see their daughter again? Was she in some imminent danger? Was there some horrible misfortune that awaited her? Should she and her husband rush to Bombay as soon as possible to be by her side? Was there still enough time or was it already too late? These and other morbid thoughts plagued her mind and she could find no peace. At length she forced herself to go back inside the house and change into her usual home clothes. She would somehow have to explain her absence at the engagement ceremony to her friend, but for now she waited impatiently for her husband to return home.

Jan Mohammed found his wife disturbed and extremely agitated as she tearfully described to him the events of that afternoon. Fearing for her daughter’s safety and wellbeing she implored:

“Sait let us go off to Bombay as soon as a ship is available to take us there. I am extremely worried about Aisha and want to be with her.”

![]()

S.S. Vaitarna

Jan Mohammed listened patiently and gently soothed and comforted his wife although he did not believe in the pointless utterances of fakirs and found that his wife’s fears were irrational. However, without ever openly admitting it, he also missed his gentle and loving daughter, and promised Hajra that he would have a word with his business partner and make enquiries about the next ship sailing for Bombay.

A new ship called the SS Vaitarna was due to arrive at Mandvi port in the next one week and the ship operators had started accepting bookings for passengers wishing to travel to Bombay. The new steamer was modern in design with three floors and twenty-five cabins and he had secured a cabin booking for the two of them. The ship was due to sail for Bombay on 8th November. Jan Mohammed also informed his wife that that very afternoon he had sent off a letter to his cousin Rehman informing him of their forthcoming trip to Bombay.

he SS Vaitarna arrived at Mandvi Port on 5th November 1888. As news spread about its arrival a lot of interest and excitement was generated around the giant new ship and throngs of curious bystanders gathered on the pier side to view and admire the vessel. Instead of its official name it began to be referred to by the popular nickname of “Vijli” or electricity since it was lighted with electric bulbs, a novel feature for the time.

Hajra had busied herself for the past several days preparing foodstuffs that she knew were Aisha’s favourites and also well-liked by other members of the family. She packed and stacked away boxes and tins filled with gur papdi, roat, pakwan, nankhatais and khajuris. Not knowing how long they were going to be away, she had sent off Sakina to her village with a month’s advance pay.

Jan Mohammad and Hajra had had to leave Bhuj early the previous day to make the 60 km ride to Mandvi and had availed the hospitality of Kanti Desai’s brother Vitthaldas and his family for their overnight stay there. Because of the rapport between Jan Mohammed and Kanti, Kanti’s brother, Vitthaldas, had not hesitated to welcome Jan Mohammed to his home. That apart, it was also widely acknowledged that Kutcchi merchants both Hindu and Muslim interacted and co-operated well with each other and that religious or caste differences did not hamper relationships between them. In fact, cultural synthesis and a blending of religious rituals and practices was a feature of Kutcchi culture with Hindu saints as well as Muslim pirs being commonly revered by members of both communities.

From the beginning of the 19th century Mandvi had become an important textile production centre and there was a thriving export trade to Africa and Arabia. Vitthaldas traded in both fine and coarse cotton cloth destined primarily for African markets. His home was located in a busy and crowded by-lane in the commercial area of Mandvi located at a short distance behind the port. It was a two-storey building with his shop occupying the ground floor with the residential quarters housed on the upper floors. Vitthaldas and his wife Ansuya occupied the first floor, whilst the second floor was taken up by their married son and his family.

Dinner that evening was a delicious Gujarati vegetarian meal and Ansuya served up an array of different dishes arranged in gleaming silver thalis. To begin with there were snack-type items such as dhoklas and patras with a spicy green chutney and a sweet and sour tamarind chutney offering a tantalizing mixture of sweet and spicy that was meant to tickle the taste buds. Next, she dished out portions of stir-fried vegetables such as eggplant, ladyfinger and spinach eaten with bhakhri, a round, flat unleavened homemade bread. This was followed by fluffy white rice with kadhi, a thick gravy made of chickpea flour and yogurt and served with fried pakoras. Hajra attempted to protest,

“You should not have taken so much trouble, behen.”

“It is no trouble at all,” countered Ansuya, “We are honoured to have you as our guests and I hope that you have enjoyed our simple, home-made vegetarian food.”

Jan Mohammed assured her that it had been a veritable feast and the meal ended with two types of sweet dishes – shrikhand and doodhpak, one being yogurt based and the other milk based. Before retiring for the night Jan Mohammed and Hajra thanked their hosts and said how much they had missed having Kanti with them that evening.

The next morning Vitthaldas and Ansuya accompanied them to the pier to bid farewell and see off their guests. Arriving at the dock they found the area busy and animated with a large number of marriage parties bound for Bombay carrying large trunks filled with bridal finery and festival clothing, sundry decorative arrangements and boxes of freshly prepared food items. Along with the large number of marriage invitees there was also a fully equipped Gujarati musical band. Running hither and thither trying to get a last-minute passage was a motley group of students headed to Bombay to appear for the matriculation examination. Amongst the other passengers waiting to board were some small family groups, a mix of British and Indian businessmen, army men and even a doctor or two.

The SS Vaitarna left Mandvi port on Thursday 8th November at 12 noon with 520 passengers and 43 crew members. She reached the port of Dwarka where she picked up a further 183 passengers taking the total passenger number to 703. She left for Porbander but due to bad weather she did not stop at Porbander and headed directly for Bombay, a port that she would never reach.

Late that evening she encountered a heavy cyclonic storm with high, gusty winds with speeds of 100 miles per hour and over. The strong winds were accompanied by torrential rain and storm surges that caused gigantic waves to rise high above the surface of the sea lashing the sides of the ship and repeatedly sending it tossing upwards only to come crashing down again in a mad seesaw. Mayhem reigned on board the ship. The screams of the terrified women and children could be heard above the crashing waves as they sat huddled together, drenched to the bone and desperately clutching each other’s wet bodies. As the ship swayed relentlessly upwards and downwards some clung on for dear life to whatever firm object they could lay their hands on only to be dragged cruelly away by the sheer force of the wind and the rain. The harried crew members tried frantically to garner all possible help to the panic stricken and helpless passengers. But hampered by the ferocity of nature, their efforts were rendered useless. Being ill-equipped to handle a tempest of such a devastating magnitude, the SS Vaitarna was overpowered and after a valiant battle with the stormy sea she was sadly wrecked and sank off the coast near Mangrol. The hopes and dreams of the 750 people on board were shattered and their lives snuffed out in the matter of a few hours.

The next day the ship was declared missing. The Bombay Presidency and the shipping companies sent out steamers to find the wreckage. But there were no survivors. No wreckage, no debris and no bodies were ever found. The ship had just mysteriously vanished and the bodies of all its passengers and crew consigned to a watery grave.

After the disaster, a number of questions and theories were put forth on the ship’s seaworthiness and whether adequate safety measures had been put in place. Did it have enough lifeboats and life jackets on board? Had there been any instance of foul play or a conspiracy of some kind? Was this a case involving the hand of the supernatural and in the case of Jan Mohammed and Hajra, had they been pushed to their deaths by the cryptic prophecy of an itinerant fakir? The questions and doubts remained unanswered.

*******

Notes Extract courtesy author Saeed Ibrahim. “Twin Tales …” is available at https://www.amazon.com/Twin-Tales-Kutcch-Family-Colonial/dp/168466344X https://www.amazon.com/Twin-Tales-Kutcch-family-Colonial-ebook/dp

Saeed Ibrahim was born and brought up in Mumbai, studied at St. Mary’s High School, St. Xavier’s College and later, at the University of the Sorbonne, Paris. He has worked in India, the UK and France in marketing, advertising, airline and travel industries. Today he works as an independent consultant and writes in his spare time. Apart from “Twin Tales…” Ibrahim has written for newspaper articles, short stories, book reviews and some travel writing. His love of history, tradition and heirlooms, evident in his book and short stories prompted a contribution to the Museum of Material Memory, a digital repository of stories linked to objects of material culture. https://saeedibrahim.com/

Leave a Reply