A Foreword

Asif Raza’s review of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s Urdu epic novel Kai Chaand Thay Sare Aasmaan (translated into English in 2013 as The Mirror of Beauty by the author himself) was written soon after the novel’s publication in 2006; not for a periodical but as correspondence with Faruqi himself over a period of ten months. That is reason enough to offer it here–as an interaction between author and reviewer. The reader is sharing his journey into the labyrinths of the written word with the writer; the author ‘reads’ the reader reading his text;. In this engagement, inflected with languorous luminosity, roles intertwine and dissolve. Like the author writing chapter by chapter digging deep into his subject and his own reading that together inspire the creative composition, the reader peers into the written text and his own reading to record his responses with love (not adulation) and a critical gaze (not contempt/condescension); love of reading and gratitude for the written word’s ecstasies fuel the dialogic and dialectical exchange.

But here’s another reason for us to offer Raza’s epistolary review: it is an example of deep reading-an immersive and reflective experience. The ‘review’ as consequence is not a god-like verdict on the writer for the consumption of that omniscient figure, the book reviewer’s followers: “A compelling original read” “Un-put-downable” “subline prose” “must-read!” SRF acknowledges the critical gaze Raza is directing at his work when he bemoans the critics’ praise for its historical research, factual details and the like and absence of comment on its “ ’narrative techniques’ and above all, what the novel wants to say about the world.”

Raza’s epistolary review is a labour of love and discovery, waiting to be read as a reminder that reading is as creative an act as writing. The Beacon

***

Asif Raza

Friday, July 21, 2006 1:18

Dear Asif Raza, I am glad the books arrived today. The English book was with the publisher for a long time. I didn’t want to add anything to what I gave him initially…

For then the book would have become very large…Right now I am giving finishing touches to Vols 11 & 111 of my book on Dastan.

By the way, did you get to my novel? What do you think of it?

Send the money when it is convenient. There is no hurry.

With best regards, Yours, SRF, July; 21, 2006

July 26, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

I have been rather diligently pursuing the task that I set up for myself this summer, of studying your works within the larger framework of the western literary theory and criticism. That necessitated visiting and revisiting some critics (especially Cleanth Brooks and I.A. Richards) and many theoretical approaches (formalism/new criticism, structuralism, post structuralism and others). Consequently, I do have now a better perspective on your theoretical position as a critic vis-à-vis other theoretical formulations and about the points of convergence and divergence between you and the others (I did, however, experience a degree of cognitive dissonance when reading your seminal “She’r, Ghair She’r…. In it you seem to be arguing from the premises of logical positivism whose ontological and epistemological premises I have always taken issues with).

I would like to know if someone in the subcontinent has done a study on you in the context of contemporary theories of literature and criticism. I am aware that many literary magazines have special issues dedicated to you. Can you help me get one or more of them? I have not yet completed reading your novel. Yet even the limited extent to which I have read it (Saleema) inspires me to venture some comments.

You remind me of Huysmans who, true to the Naturalist ideal of absolute fidelity to details, plunged himself headlong into painstaking research before writing his masterpiece, A Rebours. He studied several medical texts relevant to the symptoms of his hero’s neurosis, consulted countless specialist writings on tapestry, floriculture, perfumery, theology, jewelry etc. I wonder as to how many specialties you might have researched in the process of writing your novel, Kai Chand Thay Sare Aasmaan.[Mirror of Beauty in English]

The reportorial style in which you begin your novel tempts the reader to categorize you as a writer in the literary manner of realism and naturalism. But as he proceeds further he realizes that your narrative combines (as James Joyce did) aspects of many novelistic modes: realism, naturalism (your exhaustive description of techniques of extraction of colors, your medically precise description of death by freezing) symbolism, expressionism and the introspective mode of the stream of consciousness (for example in “Kitab”).

In your novel you seem to treat time as Faulkner does. The narrative begins as a trickle, gathers the force of a mighty river as it is fed by so many tributaries. It reaches into the dark recesses of history, into the ruins of a civilization and, as it does so, the dead begin to rise and speak in the syllables of a language that the world thought it had forgotten.

In my view, the flexibility of your method of narration, with its shifts from narrator to narrator, that is, consciousness to consciousness, third person to first person, and historical time to historical time, fits well with the encyclopedic scope of your novel.

Mahar Awwall gallops into the stage of the reader’s mind, as full of vitality as the horse he is riding on, deals the blow for which you had so deftly prepared the reader in “Tasvir”. With a few broad stokes, you ‘show’ the character in terse dialogue and condensed action. The dramatic effect is overpowering. Mahar Awwall exits the scene as quickly as he entered but is etched in the memory of the reader. And you draw his portrait in a fiercely masculine prose.

In ‘Ta’leem’ the setting and the central character gradually melt into a mystical dream vision. Your metaphysical portrait of the Ustad, dreaming the transcendental dream of ‘the color beyond colors that has no color’ is rendered in a lyrical prose that fully unveils the poet in you.

My retrospection of what I have read thus far is poised against the tension of anticipation in a mode of suspended animation. I wait to read what follows.

You might regard my comments as hopelessly impressionistic (a mode of appreciation you reject). While I was writing them, I was constantly aware that your novel needed a more competent reader than me. I would like to read how it is being received by the critics.

Aap ka Mukhlis,

Asif

Thursday, August 3, 2006 11:18 AM

Dear Asif Raza: Many thanks for your very generous and inspiring email. No, while people have vaguely mentioned Richards, Brooks, the logical positivists, etc., in regard to my criticism, no one has engaged in the kind of things that interest you. That includes the special issues you refer to.

I like your comments about the novel. They are so literate and creative and often make me look at the novel from newer angels. What more could a novelist ask for?

By the way, it is maha rawal.

Sometimes I wish I had people like you writing for Shabkhoon. Now it’s too late.

With best regards, Yours, SRF; aug 3, 2006

August 9, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

Thanks for you kind words. I find them encouraging.

It is amazing, to say the least, that as firmly as your critical work is grounded in the soil of the continental philosophy, the literary theory you expound and its hermeneutic and aesthetic principles should not have been examined in that context.

Realizing what an awfully slow reader I am, I recall Hermann Hesse who establishes categories of readers. There are those who, with a child-like imagination, pursue the beckoning symbolic connotations of every word and image, and then those who ‘swim’ in the suggestions and ideas such that a ‘Latin initial’ on the printed page metamorphoses into “the perfumed face’ of their mother”. (Rimbaud, who sees a mosque at the bottom of a pond, perfectly exemplifies that type)). I lie in between the two. Thus, though at a very slow pace, I continue to tread upon your earth and travel under your skies. I am at your “Bagh-e-Kashmir.”

I observe that carpet weaving is a recurring motif in your novel. That may also be an apt metaphor for the manner in which you have written and developed this novel. By interlacing story lines and episodes and characters, you have created patterns that are exquisitely intricate. Handling your sentences delicately, like threads of silk and filaments of silver and gold, you have woven a texture that is rich in vivid colors and cultural motifs. As for “the figure in the carpet”, it is for the critic to find. I am curious to know what the critics are saying about your novel.

I detect a certain continuity of purpose from your postcolonial literary analysis up to this novel. In your former occupation, you brought Urdu poetry to consciousness of the riches of its own pre-colonial aesthetics. In this novel, you reach down into the Unconscious of Indian history to bring it to the awareness of its cultural riches and diversity— its religion, its customs and rites, its sites and its characters. However, though it is a historical novel, it does reach across to the modern consciousness as well since it encompasses end- themes of human existence, that is to say, the existential constants of human condition.

I wince at the thought of not having your “Sh’er-e-Shor Angez” on my shelf.

Aap ka niazmand,

Asif

Saturday, August 12, 2006 2:28 AM

Dear Asif Raza:

Please note that I write your full name so as not to confuse the future archivist, if any, between Asif Raza and Asif Farrukhi and Asif Naim.

You give such sensitive comments on my novel that I almost wish you would write about it. I have never requested anyone ever to write about me and am not going to start now. But the wish is there. I’d translate your comments in Urdu, if I had the time, a rare commodity that goes scarce by the minute.

You ask: What have the critics been saying? Sadly, everyone who has written and spoken so far, while praising the novel in maximum terms sometimes, spoken mostly of the information, the “research”, the historical and the cultural detail packed into it. No one at present seems to have anything to say about the structure of the novel, its “narrative techniques” and above all, what the novel wants to say about the world.

About my criticism: Here again, I find myself wishing that you wrote about it sometime.

And again, please note that this is NOT a veiled request for you to write. Your own work, your teaching load, your other commitment, must take the fullest of your time and energies.

Reading speed: I am a slow reader myself. Urdu I read incredibly fast, partly because there isn’t much there to take in, but English is very slow, Persian slower.

With be regards, yours, SRF

August 20, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

To dwell upon your ‘information’ is the task of the historian. The critic’s task is to see how you mold that information into an art form, how your creative imagination transmutes it into the images that your prose paints, into the song that your prose sings and the dance that your prose dances. For your prose does all these things, (though it also just walks when it should, such as in the larger part of Khalil Faruqi’s narrative which is in the prosaic language of ordinary discourse.)

For anyone who is sensitive to the aesthetic quality of prose, it should not be difficult to see that the naturalist in you is often superseded by the poet. For instance in “Taleem” when you show the Ustad teaching the physics and metaphysics of carpet weaving to his students (Makhsoos Ullah being one among them), the language in which you articulate his oracular speech, is the language of poetry par excellence. The sensuous richness of the images, the dazzling similes and metaphors are not just a rhetorical flourish on your part, nor merely a demonstration of your linguistic mastery or artistic finesse, but the very appropriate form called forth by the mystico-metaphysical content. In other words, Ustad’s ecstatic oration, both impassioned and highly cerebral, calls for a language that is commensurately elevated in tone and tenor, as is the case in the following instances:

“tum rangon ke rasya ho, laikin chamakne wale rangon ki tarah shokh rang, aur cheer ke tail ki tarah chikne aur sabun ki jhag jaisi jhilmilati shaffafiyyat rakhne wale aur hathon se bar bar phisal jane wale raushan rang., jalte huve, aapas mein mutasadim laikin kisi na kisi sath par baham aamez haqeqat-e- wujoodi ki tarah apni apni khusoosiyyat ko barqarar rakhne wale rang, tumhari talash ka maqsood hain”… (p.79)

“ Insan ka wujood ghair munqasam hai- Kya tum jante ho ke jism kahan khatam hota hai aur rooh kahan shuroo’ hoti hai?…insani wujood ki tamseel saat sur, sattat rang aur saat sau zaviye hain…” (p.83)

I find it rather puzzling that you, whose prose is quintessentially poetic, albeit in flashes in the body of your book, should have been categorized as one unreceptive to the genre of prose poems. I notice that, at times, you go a step further, such as in the following example in Bagh-e-Kashmir in which Makhsoos Ullah’s son, Mohammad Yahya delivers the following rhapsodic lines (which read like a formalized prose poem):

“Marodhar, log wahan marne ke liye jate hain…Kashmir mein khizan nahin aati

Gar murgh kabab ast ke ba bal-o-par aayad

Laikin zindagi ki bahar to behr-e-zulmaat aur majlis-e aafaq se aawaz deti hai………………………………………………..

Mujhe ghar jana hai”

Aiy bakht rasan ba baghe Kashmir (p.114)

You break the syntax into lines of irregular length; the tone is poetically elevated, and the rhythms and cadences are deftly controlled:

The nostalgia that this piece evokes reminds me of Garcia Lorca’s “Rider’s Song” (though his rider is not torn with such inner anguish as yours):

“Cordoba.

Far away and alone

………………….Ay! That death should await me

Before I reach Cordoba”.

Your method of narration is an eclectic mix of the traditional and the modernist techniques. For example you sporadically disrupt the sequential flow of your narrative by interpolating sentences that are unanchored in the context. You also thwart the expectations of the traditional reader by subverting the representational convention of a logically coherent narrative so that it remains up to the reader to tie the loose ends and relate components far flung from each other in the textual space.

Thus far (which is not very far) I find Makhsoos Ullah and his son Muhammad Yahya to be the most profound characters. According to the somber and austere portrait you have drawn of them, they are essentially creatures of inwardness and solitude, meditative, and tormented by the transcendental desires of their souls. As such, they have an aura of tragic grandeur about them. In their inward experience, they suffer a lack, a void within or a ‘hole’ in their soul. Alienated from this world, they aspire after the Absolute. They are transported to a state of ecstasy and undergo a transformative experience that is akin to a theosis in the presence of beauty. One can call them worshippers of beauty, (or followers of “the religion of beauty”, to use Flaubert’s expression). They are dreamers whose eyes are hitched to the stars and, they find solace in the thought of death.

Mukhsoos Ullah longs to pass the art of carpet weaving to his son. But when his son is born, he ascetically abandons his home and family, and goes out to die, to be frozen into eternity, with his hands clutching at a portrait, not of “shabih-e haqiqi”, that is, of some real flesh and blood woman (such as Manmohini) but of BaniThani, the “shabih-e-khayali” that he himself had painted (he had once proudly proclaimed to have mastered the art of painting “shabih-e-khayali”.) There is contentment on his dead face. He departs from this world holding on to an image conjured out of his own fancy, to a portrait that was a precipitate of his own vision of absolute beauty. (It recalls to one the Mallarmean idea of art as a supreme fiction yet one that has supreme value as a substitute reality, or compensatory reality.) Did then Mukhsoos Ullah die a martyr’s death at the altar of his own beauteous fiction, by achieving transcendence through his work of art on this earth? Or did he die a mystic’s death, with his soul flapping its weary wings toward the infinite heaven of the Beloved that the mystics seek?

Yahya has his own theosis when he encounters the ‘shabih-e-khayali’. Suddenly feeling himself to be a stranger in his own house, he is seized with a strong desire to abandon his home and family and withdraw from the world. He describes his inner turmoil as “spiritual earthquake.” Proclaiming “I have found my light” he feels triumphant at the thought of his impending death, happy that the doors of his house are going to close upon him forever. It seems dying to him is going home. Or, as one might put it in the lexicon of the mystics: “Fanaa” is “Baqaa’.

Though by genre yours is a historical novel, however, as I said earlier, it can well resonate with the sensibility of an informed modern reader since you impregnate your story, plot, and characters with the themes that represent, what I earlier called “the existential constants” of human existence. Questions about, man’s place and destiny in the cosmic order, his anguished feeling of abandonment in an alien universe, the yearning of his anguished soul for transcendence… these and others are the philosophical and literary tropes that have reverberated across ages down to our own. The negative experience of “void” or lack and emptiness that your two characters undergo, has received divergent and sometimes diametrically opposed treatment, in both Western and Eastern cultures, for example in phenomenological analyses of French existentialism. But, given the well-recognized affinities between phenomenology and mysticism, in mystical traditions too such as the Chinese and Indian Buddhism. Yet, despite these reverberations that an informed reader may experience echoing in his mind, he tends to lean toward the view that in your treatment of these characters, you largely stay within the framework of mysticism afforded to you by the Indo-Muslim cultural history.

But how audacious of me to be making these statements when I have read only 139 pages of your 822 pages long novel! Then again, what other way there is to break the vicious hermeneutic cycle? So let these be my hypotheses, based on my retrospection of what I have read and anticipation of what I might read. I may modify them or altogether drop them and offer new ones if that is what the text calls for.

I do not have the key to one of your most intriguing chapters, that is, “Kitab” (written entirely in the modernist technique) which is stated to be based on Wasim Jafar’s memoirs. Who is its narrator, Khalil Faruqi or Wasim Jafar?

So much for my being your ‘commentator’.

As for my comments on your novel, they are now yours and you can do with them whatever you like, even edit out irrelevancies as you translate them..

I am enticed by your mention of the additions that would be made to the third edition of She’re Shor Angez. I therefore, opt to wait for it until January. Thanks for keeping me in mind.

Aap ka niazmand, Asif

Tuesday, August 22, 2006 3:39 PM

Dear Asif Raza, I will look forward to your poems.

My God, if you can produce so much, and such learned stuff only after 139 pages, what would you not do after you go through with it? My trouble, if I don’t agree with you, I’ll have to argue with you which is tedious and a pleasureless job in this context. If I agree with you, I’ll sound extremely egotistical. So I keep silent.

I translated your communication about the Novel and put it in a Newsletter. A copy will go out to you soon.

The narrator of Kitab is a fictional version of the fictional character called Wasim Jafar. How is that for being a big, bad novelist?

With best regards, Yours, SRF; Aug.22, 2006

Friday, September 1, 2006 12:14

Dear Asif, the publication of some of your comments in the Shabkhoon Newsletter should not let you believe that I don’t expect more comments from you, when you can.

With best regards, Yours, SRF; Sept., 2006

September 17, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

Although, in my view, none of the reviews (Dawn, Jung) measures up to the challenge that your novel poses, I am nevertheless, delighted to know that your work has caused quite a stir in the subcontinent.

Continuing the travel, I have reached “Fanny Parks”. It is as if, after climbing up and down the cliffs enwrapped in the fogs of mysticism, I have emerged onto a plateau that is lit up by the sunshine of earthly reality. It is almost like a descent from the ontological to the ontic. One can feel the change in the atmosphere and technique. From chapter to chapter, the narrative moves in a straight line.

Your main character in this new dimension, Wazir begum, is no aspirant after the Infinite but a vibrant being of flesh and blood. She is also on a quest but one that is this-worldly. In her you have developed an intriguingly complex character. A rebel, a marginal personality torn between the old and the new, a pre-feminist, a hard-bargaining, calculating rational pragmatist and an absolutist, she carries the tension of polarities within herself. With the grounds shifting under her feet, she is constantly trying to find her balance. She is constantly in search of her identity which she is ready to invent and reinvent with every twist and turn in her fate.

I am tempted to look at her as a symbol of the fall of a civilization from its former spiritual heights, rather than an embodiment of the grandeur of the Hindu-Muslim civilization, as Intizaar Hussain seems to think in his Dawn review, (unless I misread him), or as a metaphor for the schism in the Indian psyche effected by the colonial experience.

But once again, I may be rushing ahead of myself and should wait to see how you develop the character in the pages ahead.

Thanks for sending my poems for publication.

Niazmand,

Asif

Wednesday, September 20, 2006 12:45 PM

Dear Asif, I like your analysis of Wazir’s character. She is indeed a mixture of the pragmatist, the idealist, and the plain human. I like even more the idea that she symbolizes the Mughal Empire in its decline and fall. But I am not sure that the decline is spiritual. I believe it is the physical, political and military decline of the empire that she symbolizes. Extremely beautiful and sophisticated, with depth of character and strong individuality, she is unable to prevent her defeat. Intizar’s analysis too is not far out. In fact it is the obverse of your coin: the Mughal (Indo-Muslim) culture, even in decline, possesses depth and beauty and sophistication and a sort of timelessness. And that’s what Wazir was: a woman of great individuality, finesses of mind and character.

Ahmad Mushtaq called me today to praise the novel. Among other things, he unknowingly made the point that you did earlier. He said the motif of carpet weaving permeates the whole novel in the sense that the novel too has been woven like a carpet and carpet designing and weaving as depicted in the novel has mystic undertones. I told him about your comments. He was very pleased.

With best regards, Yours, SRF; Sept. 20, 2006

September, 22, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

Thanks for your e-letter.

The meeting of minds is a felicitous event! It checks one’s slide into solipsism. I am delighted to know that there is a concurrence on this point between my views and Ahmad Mushtaq Shaib’s. Please convey my regards to him.

I concede that. Wazir may symbolize more than just the “spiritual” decline of a civilization.

I am on “Gardish-e -Khama-e-Naqqash

My initial impression of Wazir’s character was that in her, I was witnessing the Indian reincarnation of Scarlet O’Hara. But you have enriched and deepened her character since.” Yet she remains elusive, which, in my view, enhances rather than diminishes her character.

In my very first review-letter, I had commented on your Huysmans-like fidelity to details. In his Dawn review of your novel, Intizar Hussain Sahib also notes what he calls your “complete mastery of details”. With the benefit of the progress that I have made with reading your novel, I am tempted to elaborate on that point a little.

Whether it is the description of the outdoor nature (myriad examples in the early part of the novel) or the ‘interior’, such as Nawab Shamsuddin Ahmad khan’s kothi, or his divan khana, or the physical appearance, apparel, and ornaments of the characters, such as Wazir Begum’s and Pandit Nand Kishore’s, you seem to exhibit an intense epistemological commitment to render an exact verbal equivalent of that which you describe. In this mode, you are so minutely descriptive that one is tempted to say you don’t just write but do linguistic embroidery (Urdu main ye ke aap mahz likhte hi nahin balke lisani kahsida kari karte hain. )

However, it seems to me, that you explode your own representational mode of narration from within, in the ‘subversive’ way in which you use the language, with the result that the mimetic world of representation, the sensory world, is replaced by a world which is unto itself, a word-created world. This transformation is effected by your extensive use of ‘synesthesia.” (Once again I see the poet in the prose). This throws me back to my earlier observation of your eclectic use of several novelistic techniques. For example your chapter “Kitab” is entirely written in the surrealistic mode.

In your novel, the individualization of your characters is deftly integrated with the chronological unfolding of the story of a civilization. Your narrative point of view shifts between the one and the other as this dialectic between the individual and society/history plays itself out. It is a testament to your acute aesthetic and artistic sensibility that you have chosen a feminine character, an ill-fated woman of exquisite beauty, taste and grace as a symbol for the beauty, grandeur and pathos of a dying civilization. That she betrays all too human flaws and contradictions, keeps her from degenerating into an idealized type, or a puppet tied by a string to some vacuous abstraction, and imparts to her character that contingent and concrete particularity which defines human existence in real space and time.

I being myself a Mughal, have a weakness for all things Mughal. I have a shelf-full of books on (and by) Mughals but with large gaps, none as blatant, it seems so now, as the period of Mughul decline within which your narrative unfolds.

Niazmand,

Asif

Friday, September 29, 2006 6:30

Dear Asif, You overwhelm me with your eloquence. Since almost all of it is devoted to praising something or the other in the novel, I have no choice but to keep mum.

I have copied a substantial part of your letter to a nephew of mine who is toying with the idea of translating, or assisting at the translation of the novel. I have asked him to show it to William Dalrymple too who is his good friend and as you might know has published/is about to publish his book on Bahadur Shah Zafar.

I’ll mention your views to Ahmad Mushtaq when I talk to him next.

Yours, with best wishes, SRF; Sept. 29, 2006

October 6, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

Is William Dalrymple too involved in translating your novel? I know he is a historian and a writer of international acclaim. (Incidentally, I have a historical novel on Bahadur Shah Zafar, titled ‘The Last Moghul’ written, in a rather stiff English prose, by Gopal Das Khosla, the Chef Justice of Punjab State). I shudder at the enormity of the challenge that is likely to confront the translator of your novel.

I have just finished reading “Bharmaru’ (the hunter that you have produced and sent him onto the hunt for his prey). The plot has thickened and the narrative is propelled forward in a straight line (unless the straight line turns out later to be the curve of a large circle). At this point, I have surrendered myself to the story and am riding the crest of its intense suspense.

The Shabkhoon Newsletter lists some works of yours that I would like to buy, that is, if possible. They ae as follows:

Tabeer ki Sharh

Aasman-e mehrab

Urooz,Aahang aur Bayan

No sign of Tashkeel as yet.

Aap ka niazmand,

Asif

Monday, October 9, 2006 1:18 PM

Dear Asif, Many thanks for your perceptive thoughts on the novel. Yes the story after Bharmaru does get straight quite a bit, though I hope the element of uneasy uncertainty remains.

I have asked Amin Akhtar to air mail the books to you…I think I will sign them for you.

Yours, with best regards, SRF; Oct. 9, 2006

October 17, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

Not much progress with the novel. I just finished ‘Dast-e rozgar’ certainly suspense and uncertainty but not the earlier ambiguities that intrigued the reader and allowed him a free play of imagination. The difference perhaps follows from the fact that what you are narrating in this part are not fictional (perhaps not even fictionalized) but determinate historical events.

I am curious to know if more reviews of your novel have surfaced.

Khaksar,

Asif

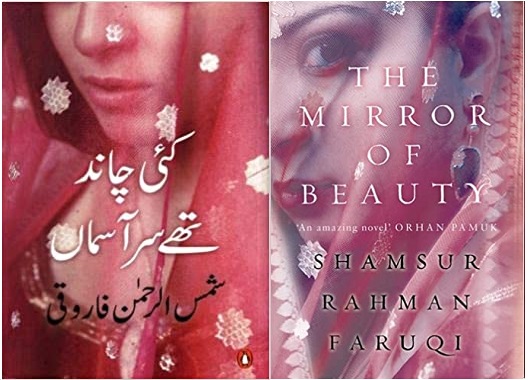

![]()

SRF with Raza

Tuesday, Oct 31, 2006 10:47 AM

Dear Asif, Thanks for your mail. Yes, a little before the halfway mark, it seems that the story has become quite straightforward. But perhaps it will gain some speed. Let’s see how you feel when you reach the end.

The packet of books must be arriving now.

Id Mubarak, and best regards, Yours, SRF; Oct.31, 2006

November 02, 20006

Dear Faruq Sahib:

I received the set of books from Amin Akhtar Sahib. Thanks.

I have gone past “Kussi”.

With great artistic restraint and poise, and in a deceptively calm and obliquely advancing prose, the reader is lured into a trap where horror awaits him, coiled and ready to strike. The moment of the strike is chilling in its suddenness and entirely effective in the vividness of its presentation.

I continue to be intrigued by Wazir’s character. One aspect of it that is enigmatic to the reader is the contradiction (to which her consciousness does not seem to have access, even in her moments of introspections) between her expressions of piety, and of her devotion to the conventional ethical and religious code on the one hand and their serious transgressions by her on the other hand, whether by inclination and willful choice (for example, her initial rebellion and marriage to Marston Blake) or by necessity. In the latter case, it is always her instinct of survival that claims victory over her moral being. One wonders if, by opting for an nonintrusive narrator, you intended a subtle irony in your portrayal of her character. However, such a reading is not substantiated given the absence of any pointer in that direction. More or less the same observation may be transferable to Nawab Shamsuddin Ahmad’s character too, that is, to his unselfconscious and unperturbed transitions between his acts of piety, observances of religious code and his moral transgressions.

Aap ka niazmand,

Asif

Monday, November 6, 2006, 10:22 AM

Dear Asif, Many thanks for your (as usual) perceptive remarks about Wazir and Shamsuddin. No, I don’t think there is any irony. Wazir seems genuinely unaware of any contradiction in her character. I of course had no intention of taking her in that direction. Or perhaps there were other women like Wazir at that time: secular, passionate, practical, all at the same time. Or perhaps Wazir makes up her own code as she goes along. Or she had some notion of ideal womanhood where a woman should be full of tenderness but also believe in fashioning her own fate. You should write about it sometime when you have time.

As for Shamsuddin, I think his code of conduct permitted all those things which seem asymmetrical to us today.

I am happy that the books arrived.

With best regards, Yours, SRF; Nov.6, 2006

PS By the way it is kassi as in lassi

November 20, 2006

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

Thanks for your e letter.

I am a few chapters away from the end of the novel. But for a ‘close reader’ like me, one reading may not be enough. I will share with you my additional remarks on your novel soon.

Yesterday, I called Adil Mansuri sahib to thank him for sending me a copy of his “Hashr ki Subh Darakhshan ho”. He told me that the same magazine that took out a special number on you is now taking out one on him. He wished I wrote something on him. I hoped to him that, if I did not, for lack of time, he would forgive me. He seemed to understand.

I hope the publication of the new edition of your “She’r-e- Shor Angez “is on schedule.

Aap Ka Niazmand,

Asif

Tuesday, November 21, 2006 6:07 AM

Dear Asif, The First volume of She’r-e-Shor Angez (revised edition) is out. The 2nd is about to go to press.I hope it will be out before the end of March.

I look forward to your thoughts on the novel. But there is no hurry at all.

Vols 11 & 111 of my Dastan came out recently. I should now get busy on the 4th Vol. I am finishing the final proofs of Kulliyate-e Mir, Vol.11. The first came out some time ago.

Yours, with best regards, SRF; Nov. 21, 2006

January 3, 2007

Dear Faruqi Sahib

At long last, I have come to the end of your prodigious novel. But first, some more comments on Wazir’s character.

As I remarked earlier, BaniThani’s painting (a shabih-e khyali”) takes possession of the soul of its beholders, such as Mekhsoos Ullah , and his son Yahya. She was to them, as I interpreted it, a beckoning glimpse of the Absolute (in fact, your association of her with Shri Radha does seem to bestow a sacerdotal status upon her). However just as BaniThani’s beauty transports them into a state of mystic rapture, Wazir’s painting casts a similar, if not the same spell, on its beholders. For example Khalil Faruqi (in ‘Wasim Jaffar). Stupefied, he describes himself as well-nigh losing his reason after beholding her “miraculous beauty.” (In fact, in quite a few accounts in the novel, the description of her features evoke BaniThani’s.)

Wazir too was spell bounded by BaniThani’s beauty, though fully conscious of her own, and its power over men. However, although entirely a worldly soul, and knowing that Bani Thani is a ‘shabeeh-e-khayali, she wants men to give her the same adoration that is given to Bani Thani. In other words, men’s way of adoring Bani Thani becomes her ideal of how a woman should be loved. That is the kind of infatuation and ardent devotion she expects from men. She wants to be loved much more than she wants to love. Wants much more to be a ‘mutloob’ than’talib’. That romantic idealism, reinforced by her immersion in poetry, lies behind much of her suffering in her relations with men. As a ‘mutloob’ she constantly judges men on the measure of her idealism and is torn with doubt and mistrust when they do not measure up. But as her character unfolds, the belief that she wants to be loved more than to love proves to be merely her vain delusion. She wants to love just as passionately. But once again, she is a romantic idealist as a ‘talib’ too. Her ideal of what a woman’s love should be is derived from poetry and legends such as Zulaikha’ love for Yusuf. This time she measures her own love on the measure of her ideal and is tortured by self-doubt when she feels she does not measure up to it.

Despite the above analysis of Wazir, she largely remains for me a figure half lit and half in shade. Or a face reflected in a broken mirror, a fragmented self, embodying many irreconcilables.

Your novel closes with the scene of a grief-stricken Wazir exiting Delhi’s Red Fort through the Lahori Darwaza in ignominy. The night is upon her. She sits in a carriage, wrapped in a chador, head bowed down, and her eyes sightless from the darkness of despair. She is being escorted by her two sons. The dream of an impetuous and ambitious youth has been shattered on the rock of reality; she has been defeated by chance and circumstance; defeated at the chess–game of life (a metaphor she often used to describe the vicissitudes of her fortune).

The ending scene above pivots the reader back to a scene at the beginning of the novel: it is the dawn of a new life for Wazir; a new horizon of possibilities is opening before her. She is sitting in a chariot, bedecked in her ‘bridal’ attire, and is being escorted out of Delhi, to a bright future, it seems, by her knight in shining arms, Captain Marston Blake.

The poignant and ironic contrast between the two scenes makes the ending dramatically very effective, in addition to imparting formal unity and structural balance to the novel.

But this scene stirs other obscure associations in the mind of the reader too.

Wasim Jaffar, in his hallucinatory obsession with Wazir, (in “Kitab”) sees Red Fort’s Lahori Darwaza suddenly lit up on a page of his book. Then upon the night air rise, slowly, like an invocation, soft notes forming a sad melodic pattern:

Pa…Ni…Sa…Re…Re

The sitarist and the ensemble are invisible; Wasim Jaffar’s frenzied imagination recognizes it: it is the nightly Raga Kamod. His delirious mind conjures up before his eyes a dark vision which he verbalizes in these haunting and heart-rending lines:

“Is raag main guzarti huvi raat ka dard aur bhoole huve lamhaat ki kasak aur aane wali subh ka khauf hai jab shamaen bujha di jaengi jab chiraghon ke sar qalam honge”.

At a generational distance from the legendary Wazir Khanun, the Raga to Wasim Jaffar might have sounded like a dirge to her passing through the dark night of Delhi into the thick fog of history into which he sees her disappearing.

Though your novel is populated with a large number of memorable characters, from my personal horizon of understanding, and for my sensibility, Makhsoos Ullah and Muhammad Yahya are unparalleled in their depth and complexity. In my opinion, these two characters, brooding, anguished, and with a tragic aura about them, deserve a detailed analysis of their own.

Thanks for getting the poems published.

Three books available out of nine! Meaning the glass is two third empty! But the optimist in me see it one third full. And that is good enough for me.

Yours,

Asif

Thursday, February 8, 2007 3:52 PM

Dear Asif, I read your excellent analysis of Wazir twice, though I think it needs a 3rd reading, for in my present state of depression I am unable to concentrate much. But I feel I generally agree with your analysis. While I was writing the novel, W.K. seemed to me a rather transparent character, but now she seems rather enigmatic. The portraits that find place in the novel seem to add to the enigma. Or maybe it’s just my obtuseness?

I am happy to hear your thoughts about the ending. I remember when I wrote the last lines, I had ambivalent thoughts. The novel itself seemed so resplendent in hindsight, and the ending seemed so tame. But a number of good readers actually like the ending, and now your remarks reinforce my satisfaction with it.

A copy of Sabaq-e Urdu containing your poems must have arrived by now.

With best regards, Yours, SRF; Feb.8, 200y

- I have saved your email for translation at some suitable item. I expect you got the 2nd Shabkhoon Khabar Nama

March 12, 2007

Dear Faruqi Sahib:

My appreciation of the ending is based (as it should be, unless one’s interest in reading is extra-literary) ) not on the actual history but the textualized history. A reader familiar with her biography (which I am not) might feel that, after tracing her life story from her birth, you could have taken it to its end and closed the circle off. But in my view, your choice to not bring the circle to a close has symbolical connotations.

When Khalil Faruqi looks at Wazir’s lost picture, discovered by Wasim Jaffar after his obsessive search, Khalil ruefully observes that it was incomplete: someone had callously torn it off. I tend to read it as symbolical of Wazir Khanum’s life of unfulfilled dreams and desires thwarted by fate. (At one time Wazir herself had wondered whether she was among those who started but could not finish.)

Before signing off on the review, I would like to offer some final thoughts, though sundry, on your novel.

Symbolism, whether disguised or undisguised, runs like a streak throughout your novel. When in disguise, you create subtle symbolic effects by the way you handle a word, an image, an object or describe an event or action. Along with creating symbols, using irony is also one of your structuring devices whereby you orchestrate myriad themes and motifs in your novel.

Chance plays a crucial role in your novel. It is chance that intertwines the destinies of Marston Blake and Wazir khanum. Her stunning beauty is revealed to the colonial captain when a strong gust of wind blows away the chador in which she sits, enwrapped, in her bullock cart. The irony: her chador, (symbol of chastity among Muslims), is blown away just when she is returning from her annual pilgrimage to the shrine of a Muslim saint. Compounding the irony, Sadakar, her father, who is very strict about her wearing a chador heaves a sigh of relief at Captain Martin Blake’s approach reasoning that but for him, she would certainly have been carried off by the marauding bandits and sold into a brothel as a prostitute (or “qehba”).Yet, as it turns out, ionically, it is on account of her relations with the English captain that she begins to earn the reputation of being a “qehba”. So much so that even long after her death, her grandson, Dr. Wasim Jaffar is outraged when he reads her mentioned as a ‘qehba’ by a highly regarded literary personage.

In the later part of your novel, one sees Wazir gradually retreating from her teenage voluntarism and move more and more towards fatalism. Wazir cites Shakespeare through Blake “As flies to the wanton boys are we to the gods.” In fact as the novel progresses, other characters, for example Nawab Shams and Mirza Fakhru, too seem to come to share a fatalistic vision of human condition.

In the chapter titled “Talib’e Aish and….” Nawab Shams is viewed through the eyes of a terrified Wazir. The reader sees the room darkening and taking on the appearance of a grave. The Nawab, is deftly metamorphosed into a corpse right before the reader’s eyes. His image, which is drawn to suggest the rot setting in a dead body, turns into a symbol of his own looming death as well as the death of Wazir’s dream of a secure life. His cheeks are sunken, his straight nose shriveled, his cheekbones protruding, his neck veins visible, and his body is cold. Wazir takes him into her embrace to warm him back to life but only for a short time, one might say. . Within a year he would be hanged and turn back into the corpse that Wazir sees him to be.

In “Shush Jehat se is main Zalim….” Nawab Shams is raised to stature of a sacerdotal figure. His gestures become hieratic and his speech oracular. This is done by way of drawing a sustained parallel between Nawab’s unfolding tragedy and the tragedy of Karbala. His farewell to his loved ones and his leave-taking amidst the loud wailings of women and children. His departure to the metaphorical ‘battlefield’ against the forces of evil, against the background of the elegiac verses being chanted by the mournful Moharram crowd. (“Run se chale aao munh mujh ko dikhlao” )

The artistry behind this scene is unquestionably remarkable, however it is the narrator(s)-privileged interpretation of Nawab’s character that the reader may have trouble with, that is, does Nawab Shams deserve to be elevated to the status of a martyr? It will not be difficult to show, on the evidence of the text itself, how such an interpretation ‘deconstructs’ itself. The reader faces similar difficulty regarding the narrator(s)-privileged interpretation of Wazir’s character, which raises the question: is the narration intended to be in the hands of an unreliable narrator? (An affirmative answer to the question is not suggested by the text).

Aap ka niazmand

Asif

Sat, 12 May 2007 16:40

Dear Asif, I am disappointed that you won’t be I in Texas when my packet arrives. I expect someone will receive it on your behalf. I have put on hold the idea to send you She’re- Shor angez until all four volumes are ready and you are back in Texas.

I expect you are going to Karachi? Could I have an address or phone number so that I may reach you if I need to?

I did enjoy your further comments on the novel. But I didn’t have the energy to give the kind of response that it so richly deserves. I’ll try to translate it into Urdu and put it in the next Khabarnama.

With best regards, Yours, SRF, May 12, 2007

********

Notes Many thanks to Asif Raza for compiling this exchange for The Beacon and also to Shamsur Rahman Faruqi for agreeing to share it with our readers.

Asif Raza writes poetry in Urdu and translates many of them into English. His poems have been published in several literary journals in India and Pakistan. Several of his original poems as well as his English translations of them were published in the now defunct bilingual journal, Annual of Urdu Studies, University of Wisconsin. He has authored three collections of poems: Bujhe Rangon ki Raunaq (Splendor of Faded colors), Tanhai ke Tehwar(Festivals of Solitude) and AaeeneKeZindani (Captives of the Mirror) published in two editions, the first one in Delhi, India (under the supervision of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, who also wrote its foreword) and the other in Karachi, Pakistan. Asif Raza came to the U.S. in 1975 on a fellowship. After a doctorate in Sociology, he taught at the University of Missouri, Columbia, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb and a senior college in Texas. He lives in Tyler, Texas

More by Asif Raza in The Beacon Tremors of the Soul: On Translation and Poetic Vision Reading “At a Window, Waiting for the Starlings” CONVERSATION WITHOUT MAPS ARCH OF MEMORIES and other poems

Leave a Reply