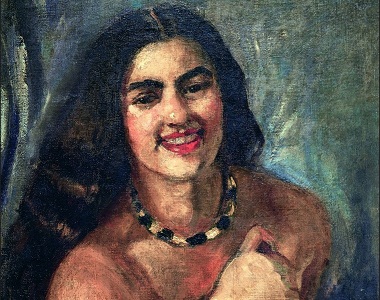

Amrita Sher-Gil. Self portrait

Gábor Lanczkor

A Prelude

Amrita Sher-Gil. She was born in Budapest, then one of the great urban centres of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, now the capitol of Hungary, and she died in Lahore, then one of the great multicultural cities of British India, now in Pakistan (where unfortunately I’ve never been). As a Hungarian poet I had to have some leader-spirits on my long journeys into the vast landscapes of India, and one of them was Amrita Sher-Gil. Hungarian mother, Sikh father – this great Indian painter who wrote beautiful letters in my mother-tongue to her mom and her favourite poet was the world-class, though unknown (as he is not translatable) Endre Ady. Just as he is mine. I have some more elusive connections to her and her work, but I can’t really talk about them in this form – that’s what poetry is for.

**

Coins From Amrita

The history of the period of the Indo-Greek princes is extremely confusing. Eucratides’ successors ruled over the North West Indian territories in a whole host of bigger and smaller kingdoms; we know of most of them only through their coins.

Ervin Baktay

Dr Újhelyi, psychoanalyst

Little Amri caught the Spanish flu during

the epidemic and almost died.

There was no doctor in Dunaharaszti.

There was no doctor available anywhere around.

They almost gave up on Amrita.

Her father prayed for her.

By morning the little girl was better,

and eight days later she was fully recovered.

After that it seemed certain the war was going to end,

the Sher-Gil family was living in the Grand Hotel on Margitsziget.

Social life in their salon was very active.

In the Christmas of 1920

a young psychoanalyst,

a certain Dr Újhelyi celebrated with them.

The close family friend Jaszai Mari too.

They should do some experiments on such a patently intelligent seven year old,

said Dr Újhelyi.

He raised his hand to the little girl’s brow

and put her into a light trance.

What were her favourite colours,

which fruit did she like,

for its shape,

which for its taste,

match the colours to the shapes,

soft dance music was playing on the gramophone,

Jászai said afterwards,

it wasn’t sure that it was proper to hypnotize

somebody like this for no good reason. Let’s go, Mari,

enough of what’s going on here.

The Sher-Gils packed their bags and left by boat for India.

At sea they celebrated

Amrita’s eighth birthday.

Ecole des Beaux-Arts

The family sailed to Bombay,

then travelled North by train,

to Delhi then Lahore.

Little Amrita slipped into her new skin: saris, chappals,

instead of frilly skirts and patent leather shoes.

From Lahore the Sher-Gils finally moved up to Shimla:

a small English hill station on a 2000 meter high ridge of the Himalayas.

A landscape of mighty waving green pine forests

The official summer residence of the Viceroy, the colonial government

and likewise of the native and English

high societies. Luncheons, plays, dinners and receptions

to satiety. Amrita drew.

Many, and most of all Ervin,

who was on a three year visit to India,

advised them to send their eldest daughter to Paris to study

for she was too talented for Shimla’s drawing classes.

The whole family went with her.

Paris! She learnt a lot, held exhibitions, successful, exotic: the Salon loved her.

Every summer Hungary,

Budapest and Zebegény, the Danube, the Balaton.

In Paris everyone, men and women, was crazy about her

and in Pest too. Just one among them, her dear cousin,

who was studying to be a doctor. He cured her of a sexually transmitted

disease,

and, maybe because it came from him, he secretly performed Amrita’s first

abortion in Pest.

Victor performed the second one as well in Buda

just before their marriage, although its certain the embryo was not his.

But Amrita had already decided to be Viktor’s wife

when the Sher-Gils returned to Shimla after five years at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

After Five Years in Paris

“I have come from the banks of the Ganges”

-Ady

After five years in Paris Amrita returned to Shimla with her family.

She painted. Led a wild nightlife.

The Parisian layer of paint inside her eyelids gradually grew drier,

and until it peeled off: it became blacker and blacker.

She travelled to South India.

Till the end of her life she never recovered from the fifteen hundred year old Ajanta cave

[paintings.

When she saw her friend Karl’s Moghul miniature collection

In Bombay she broke out

into a sweat.

In the villages

along the ocean shore she could not believe the colours she saw.

Married women in their voluminous homespun clothes,

half-dressed youngsters and completely naked children,

sprawled together, hardly bothering to take shelter from the hot sun,

under huge palm leaf fans,

the boats on the Ganges have a roof,

just like the village carts in Hungary, wagons with curved roofs,

they live in them their whole lives, sometimes I imagined my brothers and

sisters

in our childhood, I also recognized my mother,

in this way another similar half-artist, half Hungarian

Zsigmond Móricz

struggled for his need of the East preserved in his heart in the age of mechanical reproduction

yes radically

after watching the newsreel in a cinema in Pest.

In Buda

Amrita Sher-Gil the Indo-Hungarian painter’s mother

says of her coming into the world:

we were living in Buda, in Szilagyi Dezso Square, below the Castle

where there’s that brick church with a single steeple.

Later, in the 20s Bartok also lived there,

in the same block of rented flats where Amrita was born.

It may have been around the time we came to India that he moved in.

But as to what he composed during that period

I don’t know and I’m not interested,

we lived in that house in a different era, before 1914.

We lived in so many places in Hungary in those times,

I distinctly remember we lived the age

and not our rooms. Icy winds from the frozen Danube on our windowpane,

seagulls above the stained ice, in the narrow streets the snow reached to our

knees.

Amrita’s birth. Summer came. Autumn. Earlier the Spring.

The black outline of the bare tree branches on snow-covered Gellért Hill

like fine root hairs in the soil.

The bedroom wall glittered in the sunlight reflected from the snow’s surface

Amrita was born at mid-day, and outside, from the

pointed steeple of the Protestant brick church, the bell rang out.

Umrao

Amrita’s father, Umrao, was the scion of an old

aristocratic Punjabi family,

who met the mother of his daughters in London

where the beautiful Marie-Antoinette was a lady’s companion

to an Indian princess.

White complexioned, freckled, red-haired:

he married her. When he moved to Hungary Umrao cut his hair and beard.

He was a philosopher to no end.

In the First World War he cut his hair even shorter and became clean-shaven,

he never published a line.

He took a lot of photos.His ancestors used to have a curved sword.

One of his ancestors once had a friendly disagreement with an English captain

who maintained that his straight sword was better,

you could pierce with it as well as strike and cut.

The argument was inconclusive, but not long after there occurred a once in a

[life time opportunity

for the two to settle the question

when during the newly broken out Anglo-Sikh war

the captain was taken captive. He got back his straight-edged sword,

and after a short duel, the British officers were one head less.

During his Paris years Umrao became completely estranged from his wife.

He points at the food-laden dining table in Simla

and grumbles into his beard, there’s nothing here for me to eat, nothing.

At night he watched the stars through a telescope, if the moonlight was not too

[bright.

(Translated by Terry Varma)

***

An Afterword by Ashwani Kumar

With her audacious, intriguing and sublime paintings of women and rural India, Amrita Sher-Gil, is often celebrated as one of the greatest avant-garde women artists of the early 20th Century. Born in Budapest to Marie Antoniette Gottesmann, a Hungarian-Jewish opera singer and Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Majitha, a Jat-Sikh aristocrat, Amrita spent her early childhood in a villa in Ráth György Utca on the Buda side of the river Danube in Budapest The Sher-Gil family had moved from India to Hungary because Marie-Antoinette wanted to return to her home country for the birth of her children. Amrita was born January 1913, and her sister, Indira in 1914, but the outbreak of World War I prevented the Sher-Gils from returning to India. In 1916 her parents moved from Budapest to Dunaharaszti, where they lived with her mother’s relatives in this small town just south of Budapest. They lived in her mother’s family home. Amrita’s uncle, Ervin Baktay, a famous Hungarian author and painter also lived here.

Living between Hungarian and Indian roots and ‘often searching for a sense of belonging’, she studied art in Paris Influenced by post impressionists like Gauguin, she painted many self–portraits that brought her immediate success. Sometimes wearing western clothing and sometimes a sari, she not only explored her exotic hybrid identity, she also began to experiment with non-western forms of paintings such as in Sleep 1933, which depicts her younger sister Indira. Soon, her longing to return to her Indian roots became so manifest that she wrote “I can only paint in India. Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque….India belongs only to me”. She embarked on intriguingly unique artistic and personal quests to explore Indian art traditions and decided to relocate to Saraya, a village in India’s Gorakhpur district in Uttar Pradesh.

India in the mid 30s. The desire to make her father’s homeland her artistic destiny radically changed Amrita and her visual language.Her masterly control over the oil medium and use of colour, as well as her vigorous brushwork and strong feeling for melancholic composition expressed a new visual reality of the daily lives of Indian women in the 1930s, revealing what she called “those silent images of infinite submission and patience, to depict their angular brown bodies.” Living a life of what her nephew and artist Vivan Sundaram calls a “photo-dream-love-play” Amrita wrote “I should like to see the art of India break away from both [Bengal and Bombay schools] and produce something vital, connected with the soil, yet essentially Indian. I am personally trying to be… an interpreter of the life of the people, particularly …of the poor and the sad.”

At Saraya, she painted numerous scenes capturing the sensuous and vulnerable faces of Indian women. This led Amrita to “feminize Indian art” as art historian Geeta Kapur termed it and redeem the pre-colonial art forms of Indian sensuality. With her ‘fundamentally Indian’ form of art, she continued to remain connected to Hungarian roots as she painted ‘Trees’ during a year–long sojourn in Hungary in 1938-39 roughly the same size as ‘Hungarian Church’, which she made during an earlier visit to the land of her birth.

Fond of traveling and exploring newer locations, Amri, as she used to describe herself, moved to Lahore, then a major cultural and artistic centre in September 1941 and died at the age of 28 years, just days before the opening of her first major solo show there.

With her strong colours, expressive motions and powerful feminine figures, Amrita’s legacy continues to inspire artists in India and abroad

******

Gábor Lanczkor (1981) studied in Budapest Hungary and spent longer periods in Rome, Ljubljana in Slovenia and London. He is an award-winning author with twelve books; novels, poetry volumes, children’s books and essays. He is the guitarist of the band Médeia Fiai, and is involved in the musical project Anarchitecture. Selected poems in English were published as Sound Odyssey in 2016 by Poetrywala (Mumbai, India)

Ashwani Kumar in The Beacon

Cholera Conversation at Fulton Canteen

Autopsychography of Mohandas

Scattered Circumstances,Odd Geographies:A Life in Epigraphs.

Blurring Boundaries

remarkable jugalbandhi.

poet reads the paintings

across continents