Courtesy: Getty images.

“Let us praise the twilight of freedom, brothers,/The great year of twilight!/A thick forest of nets has been let down/Into the seething waters of the night.—Osip Mandelstam

And therefore, think him as a serpent’s egg…” Brutus

Padmaja Challakere

T

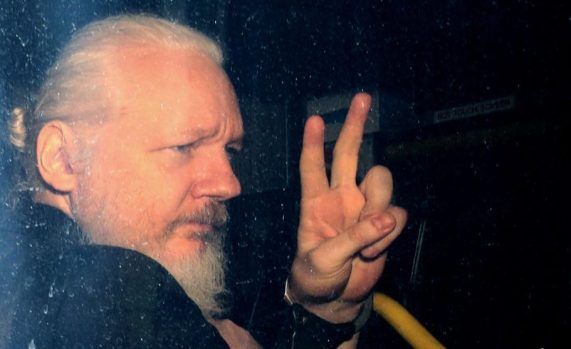

he visual image of 47 year-old Julian Assange- of his pale, sun-deprived, and aged face behind the glass screen of a police-van- giving a salute to the people has become the emblem of our times. The glass screen is transparent, and if we wanted to, we can see Assange’s predicament, and see all the ways in which the media and the Press are convicting him before the courts and prosecutors set up to do their work.

Julian Assange was arrested by the British police on April 11, 2019, and forcibly removed from the Ecuadorian Embassy in Central London when the new President of Ecuador, Lenin Moreno, withdrew Assange’s diplomatic asylum status. From March 2012 to April 2019, Assange was sheltering or “holed up” (as most media accounts like to call it) in the Ecuadorian Embassy in Central London. Thanks to Rafael Correo’s response to Assange’s request for diplomatic immunity in 2012, this necessary hospitality was made possible for Assange.

Perhaps, no one else has done more for Assange than the ex-President of Ecuador who offered hospitality to Assange for 7 years, acknowledging the need and the pact that brought them together, as this recent interview with Rafael Correo in the Jacobin reveals. For Correo, it was “about honoring the principle of the 1954 Carcass Agreement (to which Assange was a signatory) which established diplomatic asylum (granted within an embassy) as a recognized legal principle.” When Assange “showed up at the Ecuadorian Embassy disguised as a motorcycle courier,” Correo accepted the difficult responsibility of this hospitality the UK courts had warned Assange that he could be sent back to Sweden to face “sexual assault” allegations, and there was no doubt that Sweden would extradite Assange to the US.

That is why the difficult hospitality offered by Correo is significant, since neither UK nor Sweden could give any guarantees that Assange would not be extradited to the US. Raffi Khatchadourian’s New Yorker essay recounts the details of Assange’s 7- year unavoidable captivity in “the 350 feet square foot room” within the Ecuadorian Embassy now overhauled with expensive surveillance system called ‘Operation Hotel Star.’ The “tinted windows had to be kept closed throughout the day,” and food had to be checked by the Embassy staff so that Assange would not get poisoned and require a hospital visit (where he would be arrested). ’ If Assange’s 24/7 indoor-life (with occasional interesting visitors and constant police presence outside the building) seems difficult to imagine, in 2017, with Lenin Moreno’s tearing up of Assange’s immunity status, Assange’s situation turned from that of a guest (with hardships of isolation, depression, and trauma) to that of a hostage in captivity.

With predictable alacrity, the prosecutorial apparatus of the US was set in motion (as Assange must have anticipated in 2011). Assange was arrested by Scotland Yard, given the maximum sentence possible on the charge of “bail violation in 2011,” a 50-week sentence, and immediately taken to a maximum-security prison, UK’s Belmarsh prison. On May 2nd, 2019, the US charged Assange with one indictment of helping whistle blower Chelsea Manning (formerly Bradley Manning, US Army intelligence analyst) to crack a government password

Seventeen new indictments were added to this original indictment of being a co-conspirator to hack a password, with each count of the Espionage Act carrying 10 years of prison time. On June 6,thUS submitted a formal extradition request to the UK, and the UK Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, did his part by signing the papers for Assange’s extradition to the US. Julian Assange is currently detained in a maximum-security prison in Belmarsh as he awaits extradition hearings. On visiting his son in prison, John Shipton, Assange’s father has this to say:

“His[ Assange’s] movements have become fine and delicate” . . . “he doesn’t speak quickly” . . . “he is very careful about what he says,” . . . “considered in what he says — well-considered,” and “the fight is still there . . . though the fires are a little banked.”

Meanwhile, all the lies and strategies and prevaricating narratives of meritocracy are at work to turn Assange into an object of suspicion, suspicion of working for Russia, and therefore of being “a spy.”

A 102 year old Espionage Act is being used as ammunition against Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks (2006).

The US Federal Grand Jury and the Department of Justice (DOJ) with the help of the FBI and the Pentagon have stacked up 18 counts of espionage indictments against Julian Assange. Even though the whistle blowers who leak information, Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning, are vulnerable to prosecution, until now the Press and Publishers have had immunity from injunction and prosecution.

But this will change with the Julian Assange case. Now it will be possible for journalists to be prosecuted. The DOJ’s use of the Espionage Act sets a dangerous precedent for the safety of journalists.

As Stephen Rohde, historian, activist, and Constitutional lawyer points out, the 1917 Espionage Act has never before been used against journalists or against a media outlet for publishing and disseminating unlawfully disclosed information.” Rohde wonders how some of the espionage charges will play out in the court as the indictments “do not accuse Assange of stealing and leaking government documents but of receiving and publishing them.” Within the sphere of law, the Espionage Act has only been used against political opponents since it is accepted that journalists use classified information of National Security significance.

According to John Demer of the Department of Justice, “Assange is not a “journalist,” nor is he a member of the media, but is to be treated as “hostile non-state actor.” In other words, Assange is to be regarded as a spy.

To insist on the intransigence of the Espionage Act is to drastically reduce the sphere of the legal process- the due process of law- in favor of politicalization of justice.

Is the Assange case the political theater of our times? Is Julian Assange to be seen as a spy from Le Carre’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold? A spy within a new Cold War discourse of Russia’s “interference in the 2016 election”? An expendable spy within a post-Russia Gate version of Cold War? As a traitor who should be locked away for 175 years?

But a traitor to what?

Denouncing Assange, a multiple award-winning journalist and winner of the Sydney Peace Prize, as a spy is about making an example out of him. It is about exhibiting the full force of the prosecutorial power of the Department of Justice to restrict the legal protection granted by the First Amendment, which not only safeguards “the free exercise of speech, or of the press, or of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances” but prohibits all 3 branches of government from infringing the rights mentioned here. This means that neither the Executive Branch nor the Courts can restrict or abridge these protections except through a statute passed by the Congress.

Julian Assange, creator of the digital platform WikiLeaks (2006) is the active principle of journalism; of investigative journalism that matters. WikiLeaks is journalistic transparency at its best. What distinguishes WikiLeaks from fine reporting is not just the unforgiving clarity and the unconcealed nature of its evidence but its fundamental commitment to truth: truth in public interest. No one has been able to claim that any of the information that WikiLeaks has been exposing for 10 years is false news (10 million documents from different sources), or is inaccurate or untrue, or not in public interest. With effortless honesty, Assange in this interview with John Pilger, claims: “We have never been wrong.”

Yes, that is the value of WikiLeaks; that it is true, and it is in the service of the public; that is its rigid clarity. The walls of falseness erected against it are, in proportion, magnificently powerful and manipulative. Not only Washington bureaucracy but also the media and his own tribe of journalists seem keen to throw Assange to the wolves.

Julian Assange has exposed the unaccountable power of the deep state and the corruption of governments to bring newsworthy information and evidence to people around the world, to people who are not normally considered “the public:” information about CIA black sites, civilian killings in Afghanistan, war-crimes in Iraq including a classified video of a US Apache helicopter firing on two Reuters journalists, US diplomats spying on UN officials, Saudi Arabia urging the US to bomb Iranian nuclear plants, the duplicities of foreign aid, the blackmailing of government officials by corporations as in the case of Pfizer in Nigeria, Berlusconi’s corruption, the mafia state and corruption in Russia, the Libya cables, the Tunisia cables, and many other diplomatic cables that reveal the unvarnished reality of deal-making that lies behind PR rhetoric.

****

On July 25th 2010, The Guardian, Der Spiegel, andThe New York Times in collaboration with WikiLeaks published the Afghan war logs, with the Guardian running 14 pages of the relevant Pentagon diplomatic cables (less than 20% of the 250,000 diplomatic cables, as estimated by the Guardian Editor-in-chief, Alan Rusbridger). In October 2010, the Guardian published the Iraqi war logs revealing information about the use of private contractors and the prison tortures. At this time, the WikiLeaks was an admired journalism-outlet, a treasure-trove of accurate, authentic information, and the major newspapers were keen to turn this gold-standard reliable data into journalism, rich with possibilities for increased readership, profit, and new revelations. For example, the January 30 2011 New York Times article by Bill Keller titled The Boy Who Kicked Hornet’s Nest expresses great enthusiasm about the big reveal promised by WikiLeaks:

This past June, Alan Rusbridger, the editor of The Guardian, phoned me and asked, mysteriously, whether I had any idea how to arrange a secure communication. Not really, I confessed. The Times doesn’t have encrypted phone lines, or a Cone of Silence. Well then, he said, he would try to speak circumspectly. In a roundabout way, he laid out an unusual proposition: an organization called WikiLeaks, a secretive cadre of anti-secrecy vigilantes, had come into possession of a substantial amount of classified United States government communications. Julian Assange, an eccentric former computer hacker of Australian birth and no fixed residence, offered The Guardian half a million military dispatches from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan . . . . The Guardian suggested–to increase the impact as well as to share the labor of handling such a trove–that The New York Times be invited to share this exclusive bounty. The source agreed. Was I interested? I was interested.

Assange was never the darling of the Press, but this was the period of the Press’s enchantment with Assange, the heady early days; the “before.” Alan Rusbridger, Editor-in-Chief of The Guardian expresses his “respect” for the clarity and objectivism of WikiLeaks:

Unnoticed by most of the world, Julian Assange was developing into a most interesting and unusual pioneer in using digital technologies to challenge corrupt and authoritarian states . . . . At the Guardian we had our own reasons to watch the rise of WikiLeaks with great interest and some respect. In two cases – involving Barclays Bank and Trafigura – the site had ended up hosting documents which the British courts had ordered to be concealed . . . . There are very few, if any, parallels in the annals of journalism where any news organisation has had to deal with such a vast database – we estimate it to have been roughly 300 million words (the Pentagon papers, published by the New York Times in 1971, by comparison, stretched to two and a half million words). Once redacted, the documents were shared among the (eventually) five newspapers and sent to WikiLeaks, who adopted all our redactions.

Julian Assange fell out with The Guardian because he wanted to exercise more editorial control than the Guardian was willing to give him; editorial and journalistic control about what to publish, in what order to publish the material, and in what proportion to publish the material (since he was the one taking the supreme risk). Assange’s key concern was the proper order of release of the cables so that the revelations of corruption did not focus too heavily, too disproportionately on the US (and turn him, as it did, into America’s Number One Public Enemy). But for The Guardian, there was more safety in US First Amendment laws than in the British counterpart. For Rusbridger, Assange “was either an editor or a source, couldn’t be both”; and, in fact, Assange was not even a source, rather “Chelsea Manning was our source.” But what is elided here is that there would be no Chelsea Manning source but for the technical prowess of the digital platform created by Julian Assange, a platform with unassailable security.

The collaboration between the Guardian and Julian Assange went sour also because Guardian brought in New York Times because, and Assange distrusted it. Assange distrusted the gate keeping function of liberal elite journalism that pretends to eschew ideology, and claims to “make careful choices about responsibly publishing the material we consider to be of public interest,”in Alan Rusbridger’s words.

But from Assange’s perspective, the question was: Who gave you the right to determine what is in the ‘public interest’?According to Rusbridger, Assange is not a journalist but an amateur who has taken “crowdsourcing to its logical conclusion.” It is sad to see a claim to journalism being asserted through such manipulative turning of Assange into anti-journalist.

Assange is proved right about how ideologically driven establishment media (while it projects ideology to investigative journalism and maintains its stance as merely objective) is when we see the Guardian Editor, Rusbridger heaving a sigh of relief after publishing the documents in 2010: “We published. The sky did not fall in . . . . I remarked to a senior Intelligence officer that the American government, instead of condemning our role, should go down on their knees in thanks that we there as a careful filter.”

Whatever we might call this, courage is not the word we would use. The sky, as it turns out, has fallen on Assange.

*****

After Assange’s fall out with The Guardian, a new narrative emerged in the Press: in Assange’s own words, “the rhetorical narrative of a fallen man,” a “flawed,” “difficult,” “demanding,” “eccentric” man who, presumably, needs to be unmasked: “a libertarian anarchist.” In the early days, Assange was described by Rusbridger as “a visionary about the possibilities of internet” now Assange began to be maligned as “difficult,” “eccentric,” “impossible” “as an unpredictable negotiator,” and “a reckless amateur.”

The attention shifted from the truth-value of the WikiLeaks to interpretations and projections about Assange’s “opportunist” motives and difficult childhood and his eccentric personality.

The emergence of Assange as “a fallen man” who needs explaining can be clearly seen in the 2011 book WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy co-authored by The Guardian Editors David Leigh and Luke Harding, published by the newspaper, a book rushed to print with abnormal speed. Written like a TV thriller, this book about the global fame of WikiLeaks tells the story of The Guardian’s partnership with Julian Assange, and while it has a sympathetic chapter on Chelsea Manning, the book bristles with antipathy for Assange.

Here we begin to see the emergence of this different Assange; an Assange whose tragic life story explains the aberration that he is now:“irresponsible,” “narcissistic,” “egocentric,” “reckless” and “callous.” Every fact, every life detail becomes evidence of Assange’s narcissism.

Leigh and Harding dredge up every little detail about Assange’s non-middle class life: his rootless, disturbed childhood, the frequent moving from one rental to another to escape his violent step-dad, his “bad-boy” self-portrait on a dating website, the 19-hour days in front of his computer, the details of his hacker life, his paranoia and distrust, his forgetting to shower, his socially awkward frankness, his tasteless jokes, his sexual encounters in Sweden in August 2010 which later turned into rape allegations.

We get all the little things about Assange’s life but not once do we get a sense of Assange as principled and courageous. Nor do we get a sense of Assange’s philosophy of journalism or his views on anti-secrecy or his beliefs about open journalism or his faith that the public can make sense of transparency. Nor do we get any sense of Assange’s fearlessness in taking on formidable adversaries, or his intellectual abilities, or technological expertise. Assange’s commitment to the First Amendment, and his accuracy and clarity and faith in the public and his anti-secrecy is inverted and turned on its head, and Assange is accused of the very things he had been careful about: a carefully laid out plan of gradual release of documents, and his faith that the public could make sense of these revelations without journalism’s framing story.

The reader is confronted by an essentializing identity of Assange as somehow unnatural and uncaring, as a narcissist. We reach the highest levels of irony when Assange is made out to be “a reckless amauter” who cannot possibly be a journalist, or even a collaborator. What’s worse, in this book David Leigh reveals the encrypted password that Assange had given him to access the cables, so that the secret cache of unredacted cables on WikiLeaks became available to millions of users and warned off hundreds of powerful political figures around the world.The Guardian claims that this was an accident, a data-breach.”

David Liegh, of The Guardian in his recent interview is cynical enough to lambast Assange: “I don’t think Assange is against America, I think he is against everyone.” The patterns of betrayal that are now seen across the media can be traced to his Guardian WikiLeaks book. From being a crusader for transparency, Assange has now been turned into a fugitive from justice and an anarchist possibly “working on Russia’s behalf to get Donald Trump elected”.

According to Alan Rusbridger, Chief-Editor of Guardian, Assange appeared to have contempt for all journalists and for journalism itself.” And his substantiating proof is this: “Assange, solitary and reclusive, intervened in the 2016 US Presidential Elections.” The Guardian did the Brutus on Assange with their allegations: that Assange broke the law by jumping bail in order to avoid extradition to Sweden, that he has been in touch with Moscow, and that he has met with Paul Manafort, Trump supporter.

Jonathan Cook claims that not one mainstream source of journalism advocated for Assange or expressed concern about him after Assange went into the Ecuadorian Embassy. The Press during these 7 years mainly focused on Assange’s “bail violations,” and the Swedish sexual assault charges.

*****

The denigration of Assange has reached a level where the Press is paving the way for the prosecution, as can be seen in this opinion piece in The Washington Post April 11 2019, written jointly by the Editorial Board, which claims that Assange “is no free-Press hero and that Assange’s case, if carried out well, could be a victory for the rule of law.”

Assange is the man in the vortex, and the anger resulting from the failure to pin the blame on Russia for “hacking the DNC emails” and interfering in the US 2016 Elections has added to the weight of the prosecution campaign against Julian Assange. As James Goodale the First Amendment Lawyer who led the New York Times’s legal team in the 1971 Pentagon Papers release reveals in this interview with Trevor Timm, “everytime I mentioned the fact that establishment Press should advocate for Assange’s rights, I would hear hoots of laughter.”

The press and media characterize Julian Assange either as a reckless egocentric impresario or support him with calculating niggardliness, giving themselves wide alibis of caution and self-protection. Within establishment media, the distancing from Assange is loud, and, paradoxically, done through waving the flag of pathos.

On Good Morning Britain Assange’s father is interviewed, and the interviewer tries to wave away the possibility of Assange being sentenced to 175 yearsas a tragic story about Assange “bringing all this down on himself,” but Assange’s father counters this narrative firmly: “No, this is not a situation of Assange putting himself in a terrible situation. The WikiLeaks contains 3 million cables from the United States; an unsurpassed library of what shaped the 20th century, how the geo-political world is held together, composed and disposed; it is a considerable achievement.”

But the Times journalist, Quentin Richards Stephen, goes into the familiar schtick about how at a human level “my heart goes out to his father, I too have a son . . . but it is worrying when a son becomes so obsessed . . . everybody knows there are legal questions surrounding Julian Assange, improper sexual behavior etc, etc.” So, the smearing of Assange goes on in one form or another, and there is no hesitation about accusing Assange of being “egocentric and opportunist,” and at one and the same time of being an “information absolutist” and revealing “a promiscuity with facts.

Catastrophe is the name of such a manipulative trajectory of lies by which the media convicts first, and the citizenry’s capacity for judgement in relation to the conduct of the state is numbed.

Jim Kavanagh communicates the real urgency of this catastrophe when he says that we have to stop avoiding Assange now:

The consummation of his extradition and prosecution, the sight of him disappearing into the American prison system, will radically change that calculus of risk for every journalist in the world. The minute after the sentence is pronounced, every journalist and citizen will open their eyes in a world where a lot of important things they could expect to reveal and see a minute ago will now stay hidden. And they will know it. At that moment, all the bullshit irrelevancies and avoidance mechanisms will instantly dissipate, and it will be clear to everyone what the only issue always was. Too late.

Julian Assange turned 48 in prison on July 3rd, 2019. As John Pilger clarifies in this interview, Julian Assange is in a very “fragile state.”

Notes. Osip Mandelstam: Selected Poems. courtesy: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/141940/from-stone-103-the-twilight-of-freedom Also read section on Chelsea Manning: Broadening the Circle of Empathy in The Beacon:Imagining UtopiaPadma Challakere teaches high-school English in St.Paul, MN. She has taught literature and writing in liberal arts colleges in Minnesota for two decades. In the last few years, she has published essays in Counter Punch, The Hindu, The Deccan Herald, and The Wire on topics such as the Afghanistan war novel, Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Kishori Amonkar, V.S Naipaul, and Bret Easton Ellis.

Leave a Reply