The Great Indian Railways: A Cultural Biography.

Arup K Chatterjee Bloomsbury India. Reprinted 2018

Darius Cooper

A

rup K. Chatterjee is the prime engine driver in these trains of thought, and the purpose of this wonderful book, is to introduce the reader to the ever expanding archive of representation (a train whistle here would be most appropriate) of the Indian railways. As the son of a loyal PWI or Permanent Way Inspector of the Central Railway of India, let me line-clear at the outset with the author’s own insistence of that cute train song from Sholay ‘station se gadi jab chhoot jaati hai to, ek do teen ho jati hai’. Like these nau do gyaara lines, the book signifies in tantalizing numerical order vitality, progress, and the delightful critical prospect of decoding all those epiphanies brought to light that in many ways open up for me, all over again, my own private operatic love affair with the Indian railways.

Now that our train has quietly left the station, let us begin primarily with “first associations” connected with railway experience. From Chatterjee’s long list let me single out just the trinity of “food, upholstery, and suitcases.” The first summons up for me the stainlessly run Brandon railway station cafeterias, which memorialized the aromatic bread toasts that were served by the efficient Goan and Anglo-Indian waiters on the polished tables covered with green and white table cloths along with the accompanying phudinaa chai and eggs. And those numberless suitcases we packed when we went to visit my P.W.I. daddy, twice a year only, in exotic Indian villages whose names like a Dudhini or a Mohol were never found on any Indian map in any Indian atlas. Those suitcases I still remember because they tilted the tonga so crazily that they had to be evened by piling more suitcases till a balance of humans, horse, and luggage, finally tottered off like a weighted malgadi towards a dusky Poona station.

![]()

Since the book insists, not only on visualization, but also on “the industry of thinking or representing the railways,” I hope to focus on both, “the open-ended galaxy of nonfiction and the closed universe of academic writing“ that the author skillfully weaves as his locomotive gaze and penetrating intent conjure up a persistent magical interest in his fascinating subject, especially for this reawakened permanent way ex-railway boy’s sense of chamatkara or wonder. I’m coming to my first station now and I suddenly hear the “voices” of the tea vendors or the “chaiwallas” and they take me so swiftly back to the little girl of the western ghats shouting loudly about fresh “targollas” over the pounding rains next to Tunnel Nine on Monkey Hill between Lonavala and Karjat.

As my train is stalled momentarily in the western Ghats, let me endorse the author’s claim that “reading and literature almost always complete a train journey” and in a way immortalize it. Take, for instance, Chatterjee’s “second great rendezvous with the railways” that comes with the samaan of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles. Mine came with my first reading of A Study in Scarlet in Bombay-Poona’s original Deccan Queen’s first class compartment which was a sealed coupe with polished wooden walls, a freshly cleaned carpet, and ornate reading lamps. This Sherlock Holmes story, like Chatterjee’s: was an abridged and illustrated version of the novel and was presented to me as “a boon for I could read about and see how a first class carriage looked” since I was in one that exactly resembled the kind Watson and Holmes often took in their railway journeys from Baker Street to the hinter lands of England.

Now, as my train starts, sadness suddenly overwhelms me since “railway representations are now fast disappearing.” That is why it is important to spend some time focusing on the author’s resurrected examples of those “representations” in Indian cinema and Indian literature, especially for those Indians who tend to be stubbornly and even foolishly stranded in galaxies so far far away from the conspicuous Indian terrain that so memorably coaxed and guided Chatterjee’s generation and mine, flanked as we were by those two proverbial railway track lines, permanently on either side of us.

In Indian cinema, Satyajit Ray, is one of our greatest Indian railway signifiers and Chatterjee offers us superb insightful readings of Ray’s signified train moments. The train enters the chamatkara mental landscape of Apu in Pather Panchali as he runs with his sister Durga in an explosive field of kaash flowers. “This tingling encounter with a train belching black smoke” is one that none of our five senses can ever forget. Then, in Aparajito, there is another train that takes away Apu’s family to Benaras from their ancestral village. But there, as the author notes, the train further estranges Apu from his mother when she goes back to her village and he embarks on his future in the distant city of Calcutta. In Apur Sansar, the orphaned Apu first tastes a marital lyricism living in his tiny room practically “on the railway tracks.” But as another train takes his pregnant wife Aparna to her maheke and death, a crestfallen Apu tries to kill himself unsuccessfully on this railway tracks near his room.

It is in Nayak, however, that Ray really makes, as Chatterjee so brilliantly enunciates, “the luxury train function as the site of so many perpetuating desires“ that “transmute from the interiors of first class cabins, to the restaurant car” where the baring of souls is wonderfully achieved between an arrogant film star progressively humbled, both by the train’s steady rhythmic motions and the good faith permeations of an honest female interrogator.

Rudyard Kipling becomes the prime literary signifier of Indian Railways for Chatterjee and very correctly does he commence on Kipling’s “tyrannical Te-rains” with an interesting reading of all the train references in Kipling’s great novel, Kim. There is the characteristic idea of “the supposed solidarity of the characters” that joins friends and unites the anxious in “this thing,” the “te-rain,” which as the burly Sikh artisan reassures the lama and Kim “is the work of the Government.”

This spurs the academic in Chatterjee to educate us about the idea of “governmentality” as deployed by Michel Foucault from his college de France lectures delivered between 1978 and 1979. Chatterjee portmanteaus skillfully between the government’s “power” (Foucault’s singular historical idea and predominant critical utterance) and its creations of certain “mentalities” that visibly and ideologically affected “territories, communication and speed” that were first brilliantly cited by Kipling and later by Indian authors like Sa’adat Hasan Manto. Chatterjee offers scintillating readings of how Kipling, in his story “The Bridge Builders” reaffirms the “myth that the world of Eastern mystical legends co-exists facilitating the osmosis of social, scientific and even metaphysical reason aboard the railways.” But then he slyly deconstructs this idea by showing how Flora Annie Steel’s “In the Permanent Way” short story derails Kipling’s myth as being a hollow one by allowing “a whole train to go over an English railway engineer and an Indian Hindu saint who are so locked in each other’s arms” that it was hard to separate or even distinguish which was Shriver’s Martha Davy and which was Wishinyou Lucksone, semantically, historically, or culturally.

Similarly, in Manto’s Khol Do story, as Chatterjee boldly puts it, “the body of Sakina, a Muslim woman,” (during Partition) “becomes, like a railway carriage, the contested territory that must endure and obey the misogynist command of Khol do (open it) whether to remove her salvaaz or in the opening of the train’s door.” Manto painfully and shockingly illustrates here “Partitions un-sealable wounds through the technomorphic consciousness of an unconscious gang raped victim.”

Books on Indian Railways that I had previously read never solved one of its greatest mysteries for me that revolved around the enigmatic subject of A.H. Wheeler and Co. This was the railway bookshop or stall that one found practically on all Indian railway stations. Chatterjee’s wonderful history of it brings a nice Barthesian closure to it. Originally, I learnt, it was a company that started publishing literary works, with offices in London and Allahabad. What was even more surprising was that Kipling’s first published stories were inaugurated actually on our Indian railway platforms as six one-rupee volumes that came out way back in 1880. I did not know that. But I was born in 1949, and my train journeys began in 1955, and continued all the way till 1970. My frequent A.H. Wheeler trips during those long train rides related to the acquiring of my own personal Indian Railway Wheeler library that included all the Erle Stanley Gardner Perry Mason novels and all the Dell Comics of the Lone Ranger and The Sherriff of Tombstone that came all the way from America; and all the issues of Sports and Pasttime that came from distant Madras.

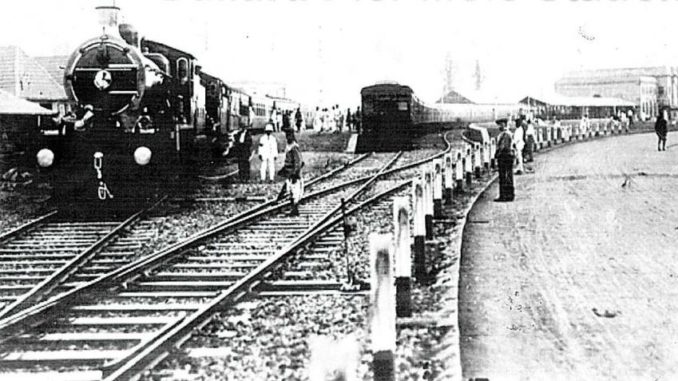

My train has once again stalled. This time we are waiting for the Deccan Queen to have first precedence. But do we really need to ponder Chatterjee’s lament of the Indian railways articulating twenty-first-century India? My answer is sadly, no. Does today’s version of the Deccan Queen, for example, evoke any kind of “nostalgia and heritage”? How could it? It is a disgusting ramshackle version to begin with–literally a bhikaree’s version of a once upon a time rani. Its carriages are filthy; the windows never open or shut properly; and it’s just plain awful during the monsoons. The luggage racks above are too tiny, and the ones below have floors that continuously leak. The seats in the chair cars are pathetic. They go neither forward (in space), nor backward (in time). There is nothing majestic or mythic about this train or, for that matter, any other train in today’s decrepit India anymore. Looking at these ugly Diesel locomotives pulling all the Indian trains today, one nostalgically longs for “the black beauties” (as those great W.P and W.G. steam engines were once called.) Since their “iron flesh” was stripped of “all their embellishments,” what we are left with today is an ugly skeleton network of what was once, undeniably, a great Indian Railway. Thank you Arup Chatterjee for at least resurrecting its ghost in all the right Proustian ways in today’s conspicuous Bharatian world of appalling mediocrity.

*******

Darius Cooper teaches Critical Thinking in the Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, California, USA. His essays, poems and stories have been widely published in several film and literary journals in USA and India A sample: Between Tradition and Modernity: the Cinema of Satyajit Ray (Cambridge University Press).In Black and White: Hollywood Melodrama and Guru Dutt(Seagull Publications).Beyond the Chameleon’s Skill (first book of poems) (Poetrywalla Pub).A Fuss About Queens and Other Stories (Om Books).

More by Darius Cooper in The Beacon:

Hindi Cinema’s Nehruvian Tryst: 2.Age of Vanishing Illusions

Hindi Cinema’s Nehruvian Tryst: I. Age of Tangled Optimism

“The Adventures of Goopy & Bagha”: Critical Rendering of a Fairy Tale.

Mourning and Melancholia: Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema-II

Mourning and Melancholia: Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema-I

Louis Malle’s Phantom India at 50: “Tabula Rasa” As Phantom

APOSTLESHIP in SANT TUKARAM and ST FRANCIS: STATE of GRACE in CINEMA

COMING HOME TO PLATO’S CAVE OR, DEATH OF CRITICAL THINKING

BETWEEN THUMBPRINTS AND SIGNATURES

RITWIK GHATAK’S ‘MYTHIC WASTELAND’

Leave a Reply