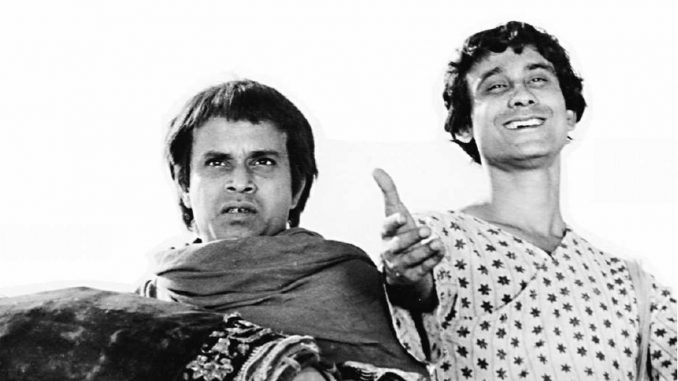

“Rabi Ghosh and Tapan Chaatterjee”

Darius Cooper

S

atyajit Ray’s first children’s film “Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne” (”The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha) made fifty years ago begins with a traditional folk–tale narrative unfolding. We are introduced to our first hero Goopy, who like Apu, is a farmer’s son; unlike Apu who aspires to be an artist, Goopy aspires to be a classical singer. His first appearance before us makes very clear the contradictions that Goopy himself is unaware of. He has a terrible singing voice that cannot hold even two notes out of the eight in any proper tune. Synonymous with his name, he displays a goofiness to everything and everyone he encounters. Instead of laboring behind a plough in his father’s field, he spends his entire day carrying a classical musical instrument on his shoulder, a tanpura. Instead of helping his poor farmer father in the field, Goopy absents himself and practices his awful singing in the nearby forest clearings. His poor father is shown constantly scolding him to change his errant ways because he does not have any musical talent worth pursuing. Goopy continues to incite his father’s anger and stubbornly refuses to change.

Classical music and farming don’t really mix, especially in a traditional Indian culture. The former is an art that was practiced usually by the Indian elite (Ray’s Jalsaghar is a wonderful exploration of this idea). Farmers really had no business in trying to ascend, as Goopy is, to a higher level. Hence, his punishment is delivered by two significant groups of symbolic father figures chosen by Ray. The first are the high-caste Brahmin village elders who in order to teach him a lesson send him off to sing below their local king’s royal window. The king is the other symbolic father who is a traditional patron of Indian classical music. When he hears one of his local peasants making a mockery of it, he summons Goopy and asks him to identify the third note, which is Ga, and the sixth note, which is Dha. When Goopy does that, his new identity is announced by the enraged king, which is that of a gadha or donkey. And since Goopy’s musical intrusions had become an intolerable beast of burden for the entire village, he is ceremoniously put on a donkey and banished from the village. In a very moving shot we see his old father wiping away tears as his idiot son is literally drummed out of the village behind him on an ass.

Ray has now advanced his tale with the sudden arrival of calamity. Goopy’s new state of isolation, completely cut off from his family and village, now makes him a nomadic resident of the forest into which he has been expelled. The forest, however, is presented by Ray in wonderfully contradictory terms. On one hand it becomes the ideal place where all exiles and idiots from normal societal standards and conventions can practice their wayward talents. But, on the other hand, it can also become a dangerous site, especially when presenting mother nature’s primitive savage world. But the forest also becomes a very important meeting place for the first Goopy-Bagha (the other hero of the story) encounter.

Ray presents this meeting brilliantly. As Goopy enters the interiors of the forest, he becomes aware of a peculiar noise that seems to grow progressively louder. Ray’s camera mimics very well Goopy’s curious and hesitant expectations. The camera stops when Goopy stops, trying to make sense of this unusual sound, and then it starts again as Goopy resumes his walking. We see Goopy, often in long and mid-shot, moving horizontally across the thick foliage, and as soon as the sound increases, Ray zooms into the forest’s interiors from Goopy’s anxious and curious perspective to locate the origin of that sound. A cut now presents us with a big drum in a gigantic close-up on which large drops of water are shown incessantly falling. A slow pan reveals Bagha, ostensibly the owner of the drum sleeping under a tree.

Goopy’s amused chuckles, now that the mystery of the sound has been revealed, wakes Bagha up. Bagha instinctively rushes to protect his drum watched by this amusing stranger. Bagha pretends, at first, to ignore him. He starts drumming his knees, stretches and yawns, cracks his fingers, only to find Goopy mocking him by doing exactly the same. This mimicry, besides being rude, reminds us critically of how similar both protagonists really are. As they subsequently exchange the accounts of their personal histories that has led them into the forest in the first place, both realize how similar their lives and ambitions have been. Everything that Goopy desires, Bagha desires as well. And the exile that Goopy has recently embraced has been the same for Bagha. Their bonding, therefore, is brilliantly achieved via that first enacted ritual of mimicry. But the mimicry also allows them to make their musical lack known to each other and bonds them firmer as the tale’s newly inscribed victimized heroes. This then sets up in the tale the beginnings of a journey in which various adventures now await both of them. But in order to provoke this journey, a new character has to enter the tale and play the role of the proverbial donor or the provider. Usually he is encountered accidentally and the forest is a perfect place for it. Also the donor’s presence is necessary because it is from him that our heroes will obtain certain crucial magical gifts which will permit them to conquer all kinds of misfortunes that await them on their new adventure. And Ray presents this donor in the guise of the king of ghosts and his troupe who are summoned to Goopy and Bagha’s presence by the tremendous cacophony they create with their first song-and-drum session after their initial accidental meeting. To rival Goopy-Bagha’s awful musical performance, the ghost king puts up an elaborate performance of his own with his troupe and after making our heroes witness it, he grants them four magical boons: unlimited quantities of food of their choice whenever they are hungry; the best of clothes suited for all Indian seasons; magic slippers that will grant them instantaneous travel anywhere; and the supreme gift of immobilizing everyone with their music in which Goopy is granted a mesmerizing voice and Bagha his spellbinding drumming skills.

Ray’s tour de force depiction of the ghost-dance moves his fairy tale into the realm of political and historical allegory. Through the dance Ray is able to depict, via his carefully invented ghosts, all those departed classes of people who had once lived in Bengal. Since they had died, they could be categorized as ghosts of their own particular histories that Ray now wishes to revive. The first are the kings and rulers who had been there from the Buddhist period. Next come the peasants who were the ruled, followed by the Europeans who conquered both classes. His last group consists of the corpulent class who were the most sycophantic—the Hindu banias (men from the trading castes), the shrewd and ritually overfed Brahmin priests, and the Christian padres with their donation box and crucifix.

The practice of colonialization is slyly indicted when the Englishman is shown repeatedly rejecting the hookah prepared for him by his servant. And religious fundamentalism is also humorously parodied by showing the christening padre, shaking his holy book, the Bible, repeatedly at the fat Brahmin pundit responding in anger with his holy Vedic books and the Gita.

Each of these four classes had to be musically defined in particular ways as well in order to provide inspiration for Goopy and Bagha witnessing the musical execution. Ray uses a special percussion ensemble from the south, called chalavadyakachiri, for this wonderful inventive presentation. An appropriate musical instrument is chosen for each of the four classes. The traditional Mridanga is given to the rulers because of its inherent classical status. The Ganjira is given to the peasants since it is a very popular instrument of folk music. The Europeans get the Ghattan which is nothing more than a clay pot and produces very rigid and rough sounds. For the corpulents, Ray provides the Mursring, a tiny instrument which is held between the teeth and plucked with the forefinger.

The dance is worked out like the gradual unfolding of a raga. It starts in a slow movement, the slow tempo being maintained by all four instruments until it reaches a middle level. Then the tempo starts increasing till it climaxes to the fastest in five successive movements. The musical climax is paralleled, at this juncture, by the choreography which now depicts a clash between all four classes fighting each other violently, and as a result, perishing. But the dance does not end here. Ray adds a musical coda in which all four classes are shown reasserting a musical harmony amongst themselves. As ghosts, they are reminding the humans like Goopy and Bagha (and us) that there is never any internal conflicts among ghosts, and when problems, from time to time, do arise and force them to act in negative ways, they have to be overcome and subdued till harmony is finally restored. That is how law and order is maintained in the ghostly kingdom. If Goopy and Bagha are going to be heroes from now onwards, they will have to strive to repeat this same exercise of harmony amongst the world of men and restore peace and happiness wherever they go in the real world itself.

After the dance the ghosts leave, and after a good night’s rest, the first song Dekho re nayan melejagater bahar is presented to us in Goopy’s newly acquired mellifluous voice and Bagha’s magical accompaniment on the drum. In the song both musicians are telling us, almost in a Wordsworthian vein, to “come and see and hear the splendors of the world, here provided by nature.” The song is a celebration, not only of nature, but also of their own transformation from hopelessly out of tuned musical idiots to refined musical artistes and vitalizes for us their music as being their most powerful tool that they will learn how to regularly use from now onwards. Their essence and their existence is now overwhelmingly tied up with their music and when Goopy sings and Bagha plays, the entire world will have to stop, listen, and obey their musical commands woven skill fully through their sangeet or music. The second song, Bhuter raja dilo bar or “Boons provided by the King of Ghosts,” is offered next to test the validity of the three other boons. And since all this singing and drumming exhausts them, they settle for their first lavish meal that magically appears with cushions to sit on, plates to eat from, and a pair of magic slippers ready to take them to any destination of their choice. After making a few comical errors in choosing lands that are either too cold or too hot, they finally stumble on a ‘classical musicians’ party on their way to participate in a musical contest being held in the distant Kingdom of Shundi. Our intrepid heroes decide to follow them and test out their newly acquired musical skills amongst the land’s legendary ustads or masters who are going to be present at the competition.

This enables Ray to provocatively anchor his tale in the two remarkably opposed kingdoms of Shundi and Halla into which our two heroes are now going to be spatially transferred and from time to time, distributed. In the traditional folk musical syntax, two basic plots are repeatedly invoked. One is called hierogamy and the other is called apocalypse. The hierogamy plot usually takes place in a world where stability, peace, harmony, and happiness exist in spite of a major obstacle that has created a momentary climate of unhappiness and a looming one that threatens to take away all familiar day to day signs of happiness. The kingdom of Shundi offers this plot to our two heroes. When the spy is asked by the evil minister of Halla to define Shundi, the spy tells him there is always “peace” there. The people are “happy” and always “helpful,” even when a mysterious malady has rendered all of them “dumb.” But they manage all their daily tasks “without complaining” and their king, who has been spared this malady because he was away on a pilgrimage wonders what he can do to make his happy people talk and hear again.

Here Ray inserts a new personage who can be termed as the villain of the tale whose main function is to disturb the peace of this happy nation and cause deliberate misfortune, damage, and harm. The wicked minister of the neighboring kingdom of Halla now enters the tale to provide it with the appropriate apocalypse plot that implies preliminary suffering, dark hours for a chosen victimized mankind, and an extended period of fear and trembling that inverts everything that the hierogamy plot has established. It privileges destruction over creation; emphasizes separation rather than unification; and is hell bent on violent endings rather than fruitful beginnings. The neighboring King of Halla (the Shundi King’s twin brother) is shown to be in the powerful grip of magical spells and strong drugs constantly administered to him by a cunning magician Burfi who has been engaged cleverly by the king’s own evil minister, who apart from robbing and oppressing the Halla people, is now preparing to invade and annex Shundi and become the sole ruler of both kingdoms. When he hears about Shundi’s hierogamic existence from the spy, he is, in fact, overjoyed. His apocalyptic perspectives evaluate Shundi as being totally unprepared for any kind of war and conflict with no weapons and no armies to protect its subjects since they seem to be totally absent in its blissfully peaceful and prosperous existence. Shundi, therefore, seems an easy “cherry” to pick (like Wajid Ali Shah’s Oudh was for Lord Dalhousie in Ray’s powerful depiction of a similar colonial intent in his The Chess Players).

What stands between him and his apocalyptic designs, however, are two rustic peasants from the land of Bengal who with their singular musical talents of songs and drumbeats are going to prevent a war between those two kingdoms, unite them and establish a place where everyone, in the appropriate fairy tale ending, lives happily ever after.

Goopy and Bagha waste no time in establishing their credentials in Shudi before the King at the Musical Contest, through their third song Maharaja, tomareselam, mora bangladesh erthekeelamor “greetings to you, maharaja, we come all the way from Bengal.” This song is important because even when it musically moves from one astonishing musical key to another, what it expresses as a whole is the idea that even though they know no other language except Bengali, there is another language that transcends all places, time, and even people. That language is universal and everyone can understand it, because it is the language of singing, of music. The song also stresses the idea of humility. The singer and drummer announce themselves as simple ordinary Bengali peasants who travel from one land to the next as troubadours establishing peace and harmony. People do not understand the language they speak. But understanding immediately dawns on them when their song is sung and their drum is beaten. Such an admission wins them not only the coveted prize in that competition, but the Shundi King is so overjoyed that he invites them to stay at his palace as his honored guests.

While enjoying their first luxurious holiday in his opulent palace, Goopy and Bagha learn from their generous royal host the history of that sad epidemic that has taken away his subjects’ speech. As they entertain the king, next day at his silent court, by launching into their fourth song, almost in a Homeric Odyssian way of telling an entertaining story, O Raja, shonoshono, or “Listen, listen O Maharaja,” an emissary arrives from the neighboring kingdom of Halla with a threatening declaration of war, leaving the stunned court with an ominous warning “surrender, within three days or else…” At this horrible juncture, where once again catastrophe threatens, our heroes intervene, assure the dejected monarch that they can avert this impending war, and putting on their magic slippers, fly into Halla to investigate what ominous things are going on there.

They first witness a frustrated military Halla general trying in vain to exercise the Halla soldiers in preparation for their upcoming war. But the soldiers refuse to comply They haven’t been paid for months. They next encounter the deranged and drugged Halla King. He is fuming with rage because his treasury is empty. He orders his evil minister (who of course has swiped all the money from the treasury (and his soldiers’ monthly salaries) to produce all those poor Halla peasants who have defaulted on their taxes and threatens, like the Queen in the Alice story, to “cut off their heads.” Goopy and Bagha, who have disguised themselves as peasants, are caught and they use their next song Ore Bagha, ore Goopy, ebarbhege pari chupi chupi re or “O Bagha dear, O Goopy dear, let’s make off from here, but softly softly” to escape the appearance of a grinning executioner who adds more spirit to Goopy’s singing and Bagha’s drumming and the immobility that this song imposes on all the soldiers rushing towards them helps in accelerating their flight. But again, we see how Ray’s song, cast in a traditional Carnatic vein here parodies humorously the jerky Bharatnatyam neck and body movements that Goopy and Bagha dutifully mimic while rendering this particular song. Unfortunately, Goopy and Bagha are caught while eavesdropping on the minister’s interview with his spy and later with Burfi, the magician. But they manage once again to immobilize everyone with their sixth song, Ore thaam, theme thaak, o mantrimashaior “Stand still, you lot, stand still, O mister Minister, Mr. Conspirator.” In this song, we notice how Goopy is not only singing to save his life and Bagha’s, but by addressing the evil minister as a conspirator, he is performing, in addition, the role of a musical commentator and critic as well.

His song is making a dramatic point about people who deliberately create war for their own selfish and powerful needs like this Halla ministerial villain. So the song is unleashed almost like a devastating verdict.

After their escape, they become a little careless and sated with yet another abundant meal, they fall asleep and are pounced upon by a vigilant guard of the king and put into prison.

The minister, with Barfi’s help, administers a very strong drug for the king, and turns him into a warmongering maniac, compelling all his administrators to join him in a crazy war dance that he further instigates with a crazier martial song Achoohethajataamir o omaraor “Come, all nobles and ministers.” Ray heightens the king’s cries for “war, war,” with heavy orchestration where even the violins, cellos and the rest of the instruments seem to get infected by it. But counterpointing this song at the moment is Goopy’s sad song sung in his prison cell which is directly addressed to our insane king, Ek je chillo raja-tar bharidukhor “there was once a very unhappy king.” For this song, Ray uses just two instruments, the dotara and the violin. The dotara is a string instrument in folk music, constantly used in Bengal by the Bauls. Since it emphasizes do taras or two ness, (for the Bauls it invokes the debate between the devotee and God), here it shows Goopy’s calm responses of peace to all the king’s strident tones of war. The solitary violin also contributes powerfully by answering the frenzied orchestral ensemble of violins in the orchestra, thereby reaffirming Goopy’s repeated pacifist message against the King’s violent declarations of war. Goopy’s song magically reaches the King, who has now retired to his chamber, and partially restores his senses. We see the hyper monarch collapse and ask his minister, “When shall I be free?”

The villain minister now has his plate full: trying to manage a king with wild emotional swings; compelling an unpaid platoon of soldiers to finally go to war by drugging them with Barfi’s magic; being abandoned by his favorite magician who subsequently vanishes, and finally dealing with two rogue foreigners in his prison. All in all, he is shown to have reached the end of his rope. Goopy and Bagha, meanwhile, have escaped by luring their half-starved sentry into their cell to partake of their latest lavish meal. Two more songs are delivered by our heroic duo as they now step into the battlefield to stun the newly awakened soldiers of Halla to a finite pacifism. What their ninth song starts, Ore baba dekhocheyekatosensachalecche samara or “My God, look at all these soldiers going to battle” their accompanying tenth song completes by asking them to lay down their weapons if they wish to live and be rewarded. Ore hallarajarsena, torayuddha kore karbikita balor “Come, soldiers of Halla, what is the use of war?” The army is frozen and when it emerges from the musical spell cast upon them, it is rewarded by pots and pots of magical sweets dropping from the sky. In the ensuing scramble for acquiring this wondrous manna from heaven, Goopy and Bagha manage to abduct the Hallaking who has run all the way into this warlike space from his chamber, and fly him to be reunited with his brother at Shundi. As for our evil villain, the last time we see him, he is sprawled on the ground, unable to acquire his pot of sweets since it has been smashed by his own mad soldiers now threateningly surrounding him.

While the villain is left to meet his own desserts, Goopy and Bagha, who had also obtained the magical cure for the Shundi subjects dumbness by learning of it from eavesdropping on Burfi, release it all over the kingdom as their final boon. Now only the question of how both these peasants from Bengal should be rewarded remains. It most fairy tales, what the heroes usually obtain as a reward is their impending marriage usually to the processes who are, of course, the daughters of their grateful masters. The happy Shundi monarch proposes that Goopy should marry his daughter because she happens to be as tall as him. Bagha, who is comparatively shorter, protests, but the Halla king intervenes, offering his short daughter as the accompanying prize. The tale ends with the nuptials of both heroes being celebrated in a vibrant splash of color.

While this ending is perfectly achieved within the fairy tale narrative structure, it opens up, on the level of gender, a problematic critical area of inquiry which focuses on the overwhelming patriarchal nature of this story as narrated and executed by a master storyteller. The arrival of the two princesses, only at the closure, suddenly reminds us of a conspicuous feminine lack displayed right throughout the film. Goopy and Bagha have no mothers. We don’t see any woman figure, either in Goopy’s village or in his raja’s court. The two kings of Shundi and Halla seem to possess no wives also. Even the general populace of these two kingdoms with whom our two heroes occasionally rub shoulders are totally devoid of any women.

The first time one of the princesses is shown as actually entering the narrative space is when both heroes are getting ready to fly into Halla. It is Goopy who looks up and in a long shot, Ray cuts to the shadowy figure of a princess, in extreme long shot, looking at him from a palace balcony. Goopy summons Baghato reaffirm his vision of whether that shadowy presence up there could be a princess or even a maid since they had seen neither when residing in the palace as guests. Bagha insists it has to be the former because of her fair complexion which is occasionally seen through the blur of whatever else is trying to conceal it up there on the balcony. Since the first presence of a woman is offered in this enigmatic exchange from the troubled gazes of our male heroes’ perspectives, her independent feminine presence is still not in any way confirmed.

Another area where the subject of princesses (and not the women themselves) first manifests itself within the narrative is when Goopy asks Bagha to list all his preferences that he would like to acquire and fulfill in his life. Bagha responds by reminding Goopy that one of his most important one happens to be “marrying a princess.” Goopy is surprised, because Bagha, being of a lowly peasant stock, is offering him here a preposterous wish fulfilment. “Where will you find a princess?” he demands in mock-heroic terms, but the realist Bagha confidently assures him (and in a way also alerts us to the film’s fairy-tale ending) that “there are so many kings and so many kingdoms, and we can’t find a princess? One has only to pick and choose.” This conversation takes place in the forest after their first lavish meal. If food is now going to appear so regularly and so magically, then what is to prevent them from acquiring princesses who will also be given to them in the same magical way.

So, when the princesses do appear at the end of the film, Bagha’s prophecy is confirmed. Sure, the women may be prizes offered to reward all the hard work they have put in to unite and join, not only two families, but also two kingdoms, but the princesses in their own symbolic ways confirm for us the worth of these two peasants who have indeed come a long way, a very long way on their pather panchalis that began with the paths outside their modest huts in their villages and ended remarkably in the marble corridors and sprouting fountains of the palaces in which they will now reside with their two appropriately beautiful consorts.

Mihir Bhattacharya starts his excellent essay “Conditions of Visibility: People’s Imagination and Goopy GyneBaghaByne” by discussing “the disappearance of women” from the film.1 He deepens the argument by linking this disappearance to “narrative desire and patriarchy”2 in the film. Women are allowed in the film under certain pre-arranged “conditions of visibility” which like him I have pointed out in my essay as well.

Ashis Nandy‘s essay “Satyajit Ray’s Secret Guide to Exquisite Murders: Creativity, Social Criticism, and the Partitioning of the Self” from The Salvage Freud3 offers the best evaluation of Ray’s masculinly inclined universe in his short stories for children and by implication one can apply them to Goopy GyneBaghaByne as well since this was his first children’s film as well.

According to Nandy, Ray’s adventure stories borrow notably in their constructions, the proverbial and popular world of “the classical Victorian thrillers, in Arthur Conan Doyle’s and G.K. Chesterton’s works.”4 Women made marginal and subservient appearances in the Sherlock Holmes’ stories. For example, Irena Adler was the only woman who Holmes might have fallen in love with because she had a mind that was the equal of his. (Billy Wilder, in fact, did take the marvelous unprecedented step in making Holmes actually fall in love with an Irena Adler like female spy in his wonderful romantic homage The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes). But in Conan Doyle’s Holmes canon women were subordinated because they were depicted as problems that Holmes had to first confront, aid, and finally solve. They were interesting to him because of the mysteries they were involved in. Once he solved the enigmas, he ceased to have any further interest in them as women per se. Any kind of romantic entanglement, in fact, would have been ruinous to the logical and deductive methods employed so painstakingly in the solving of their cases.

Similarly, while Ray explored women as “formidable material as well as conjugal presences”5 in his important women-centered films, in Goopy GyneBaghaByne, “the issues of gender and potency enter the scenes indirectly”6.

But even in his women-centered films, Ray has very few erotic moments. Conjugal fulfillment of a sexual nature is indirectly conveyed in ApurSansar by Aparna’s hairpin we see Apu playing within his tiny shack located near the siding. In Mahanagar there is the quick suggestion of a stolen kiss between Aarati and her husband, but it is behind a mosquito net in a tiny and cramped joint family room often scrutinized by the constant intrusive gazes of three generations housed there. It is as late, as in GhareBaire that Ray finally allows the noble zamindar Nikhil to boldly “kiss” his wife before his camera in the accustomed “English way,” of course. But that is in keeping with the liberal westernization that Nikhil is trying to educate his wife in, determined as he is to liberate her from her all-consuming conservative Bengali feminized spaces. In Charulata, Charu commits a bold act of adultery, but it is a mental one. The only time she actually touches Amal is when she breaks down and clings to him on the day Bhupati’s funds are stolen by her rascal brother. This is conveyed, but once again, indirectly, as a sign of yet another impending betrayal following the one she has already committed in her mind. It has yet to bear any physical consequences. Ray does allow his camera to hover over Hari and the tribal woman Dulli as they prepare to make love outdoors in Aranyar Den Ratri, but once the suggestion is made apparent, he discreetly withdraws. That film’s most striking erotic moment, in fact, is achieved, but again indirectly, when Sanoy is shown actually fleeing from the grieving widow’s overtly offered sexual advances through a claustrophobia of sweat surrounding a hastily abandoned table on which a coffee cup is shown slowly being covered with a shameful skin of cream.

Nandy is very clear when he says that “Ray’s popular fiction is set in a nearly all-male world. If Ray’s cinema tends to shrink from the details of man-woman relations, the tendency is even more apparent in his fiction,”7 and, I would add, in GoopyGyneBaghaByne. Here, we must note, that Ray’s main audience, are pre-pubescent children, especially boys who are wanting to adopt Goopy and Bagha as their heroic archetypes in the same way as the Victorians (and later on, even us, as the colonized readers of such fiction) adopted Holmes and Watson, and why not, even that Napoleon of Crime, Professor Moriarty, who, I’m sure, was a great hero for the subversive schoolboy, both in London and Calcutta.

“It may be true,” Nandy informs us, “that in Ray’s stories there is no crude attempt to provide a moral, but the Brahmo concept of what is good for children”8 informs all the actions of our heroes in the film. Ray’s very positivist “masculine concern”9 for his two protagonists enables him to define all their actions, without any exceptions, taking place always in a magical “two-dimensional, materialistic, phallocentric world where puzzle solving and a certain toughness predominate.”10 Goopy and Bagha cannot be distracted from their adventurous goal, which is to unite the two feuding brothers and their respective kingdoms. Had they even glimpsed any woman while they were living the good life in the palace, such a moment would have spelt disaster and weakened the narrative and their resolve considerably especially for the boy-audience that wants Goopy and Bagha to perform only heroic actions like punishing the villains instead of composing love songs for damsels and later running around trees with them. No palace princess or village belle is allowed to distract them.

One of Ray’s most compelling contributions to cinema lies in his musical compositions of songs and the skillful use of film music composed for the films by him. Somebody, with a deep and profound knowledge of Western and Indian classical and folk music should, in fact, write an entire book on this fascinating subject. The Ray oeuvre needs such a critical enterprise urgently. The one essay that inaugurates this concern promisingly is Suman Ghosh‘s thoughtful and incisive analysis of “Ray’s Musical Narratives: Studying the Screenplay of Kanchanjungha.” He takes his cue from Ray’s conversation with Georges Sadoul where he describes Kanchanjunga (Ray’s first original screenplay)” as a kind of rondo, in which one begins introducing the elements ABCDE [which] then return a certain number of times.12 In his interview with Udayan Gupta, as published in The Cineaste Interviews, Ray discusses Kanchanjunga as telling “the story of several groups of characters as it went back and forth…between group one, group two, and so on. It’s a very musical form.”13 (italics are mine)

To get all the musical references correctly in GooyiGayneBaghaByne, I consulted Ray’s own musical responses given in great detail to the guest editor of the Bengali magazine Kolkata, Karuna Shankar Ray, who was a learned barrister just returned from England and intrigued by Ray’s cinematic work in many areas, including music. These responses I found published in English as “Two Interviews: His Longestand his Last” in Ray in the Looking Glass, edited by Jyotirmoy Datta.14 Ray’s music explanations opened up for me many critical concerns related to the ways in which he incorporated his music and his songs into the film’s narrative.

But starting chronologically (in both ascending and descending notes), it was in the special Satyajit Ray issue of Montage, published by Bombay’s Anandam Film Society and edited by Uma Krupanidhi and Anil Srivastava in 1966 that an entire section, for the first time, was devoted to “Ray’s music” in explaining many crucial musical aspects connected with his films. In a section entitled Process, Ray informs Montage: “Since Teen Kanya, I have taken to composing the music for my own films. Before that I had worked with Ravi Shankar (four times), Ali Akbar Khan and Vilayat Khan (once each). The reason why I don’t work with professional composers any more is that I get too many musical ideas of my own, and composers, understandably enough resent being ‘guided’ too much. Of all the different stages of film making Ray found that “the orchestration of music needed (his) greatest concentration.”15 In his interview with Folke Isaksson, Ray explained that Vilayat Khan, who composed the music for Jalsaghar “loved the film, but he didn’t see the point of feudalism dying out. He had great admiration for this character and composed the most wonderful noble themes for the film. Had Ray written the music himself, “I would have given it an ironic edge to it, even from the beginning, suggesting the doom that was coming. But for Vilayat, it was all sweetness and greatness.”16

Vanraj Bhatia, while commenting on “Ray’s Music in Charulata” in Montage, feels that Ray has made “steady progress in technical excellence from the fumbling attempts in Kanchanjunga (Suman Gosh’s essay clearly repudiates this!) through Mahanagar to finally Charulata where it is the musical background that is largely responsible for the tone and the exquisite mood of the film.”17

Andrew Robinson, in his The Apu Trilogy: Satyajit Ray and the Making of an Epic offers us a precise summary of all the ragas chosen by Ravi Shankar that Ray inserted as musical moments to re-inforce the narratives. It is educational to go through this list which lacks, however, a musical explanation: “Raga Desh was used in the dance of the insects before the monsoon. Raga Todi after the death of Durga. Raga Patdeep for Sarbajaya’s grief (all in Panther Panchali). Raga Jog with the sudden flight of pigeons after Harihar’s death. Raga Jog again to suggest Sarbajaya’s loneliness in the village (all in Aparajito). Raga Lachari Todi to represent the poignant Apu-Aparna relationship. As for the music, scored for flute and strings, and composed like a Vedic hymn, that was inserted whenApu threw away the manuscript of his novel (all in ApurSansar).18

In his own writing Speaking of Films, this is the way Ray describes Harihar’s reactions to Durga’s death inscribed in the Pather Panchali narrative as a powerful and evocative “musical moment.”

“‘Shot 11: Now we come to the sari. Harihar has brought a sari for Durga, but she is no more. Harihar does not known that. So—quite unperturbed—he offers it to Sarbajaya. Will Sarbajay be able to maintain the enormous self-control that has so far kept her from breakdown?

The sound of wailing has an element of horror in it. In order to avoid that, instead of the natural sounds of Sarbajaya crying, we played a sad tune on a taar-shehnai using Raga Patadeep. It was as effective as a wail. I believe the pathos deepened with the music.19

Again, in his interview with Andrew Sarris, he explains this very same, emotional moment in a highly philosophical but musical vein:

“You are asking me why I went from a human to an instrumental sound at this particular moment? There were a number of reasons. First of all, I felt that the impersonal instrumental sound would give a more universal quality to the expression of grief, and to its effect on the hearer, a quality that the individual outburst of the women could not give. Then again, I felt that my actress, excellent as she was, could never achieve the kind of effect I was after.”20

As one can glean from all of these wonderful utterances, Ray musically Gynes and Bynes like a true maestro.

*******

Author’s Notes 1Mihir Bhattacharya: "The Disappearance of Women" from Conditions of Visibility: People's Imagination and Goopy GyneBaghaByne in Apu & After: Revisiting Ray's Cinema. Ed. by Moinak Biswas, Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2006 (140-191). 2See, Bhattacharya's "narrative desire and patriarchy" section from Conditions of Visibility, (147-153). 3Ashis Nandy: SeeChapter "Satyajit Ray's Secret Guide to Exquisite Murders: Creativity, Social Criticism, and the Partioning of the Self" in The Savage Freud: Calcutta: Oxford University Press, 1995 (237-266). 4Nandy, in part III of his chapter, (255). 5Nandy, in part III of his chapter (252). 6Nandy, in part III of his chapter (252). 7Nandy, in part III of his chapter (255). 8Nandy, in part III of his chapter (263) 9Nandy, in part III of his chapter (263). 10Nandy, in part III of his chapter (263). 11Suman Ghosh: " Ray's Musical Narratives: Studying the Screenplay of Kanchanjingha" in Apu and After: Revisiting Ray's Cinema. Ed. by Moinak Biswas. Calcutta: Seagull Books 2006 (116-139). 12Suman Ghosh, (133). Note: The interview with Sadoul was published in "A Wide Angle View" in IFSON, Special Number (as extracts from Sadoul's conversation with Ray in Cahiers du Cinema). (61-62). 13Udyan Gupta interview with Ray in The Cineaste Interviews. Ed. by Dan Georgakas& Lenny Rubenstein. Chicago: Lake View Press, 1983. (382). 14See Ray in the Looking Glass. Ed. by JyotirmoyDatta. Calcutta: Badwip Publications, 1993. Especially Ray talking on GoopyGayneBagha Bayne. (31-47). 15See Process in Montage: Special Issue on Satyajit Ray. An Anandam Film Society Publication. Ed. by Krupanidhi&Sriyastaya, No 5/6, July 1966. (no page numbers) 16"Conversation with Satyajit Ray" with FolkeIskasson in Satyajit Ray—Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007. (44). 17Vanraj Bhatia: "Ray's Music in Charulata" in the Montageissue. (no page numbers). 18The Apu Trilogy: Satyajit Ray and the Making of an Epic by Andrew Robinson. London: I.B. Tauris. 2011. (87). 19Speaking of films: Satyjit Ray. India: Penguin Books. 2005. (42-43). 20Interviews with Film Directors. Andrew Sarris. New York: Avon Books, 1967. (417).Darius Cooper teaches Critical Thinking in the Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, California, USA. His essays, poems and stories have been widely published in several film and literary journals in USA and India

A sample: Between Tradition and Modernity: the Cinema of Satyajit Ray (Cambridge University Press).In Black and White: Hollywood Melodrama and Guru Dutt(Seagull Publications).Beyond the Chameleon’s Skill (first book of poems) (Poetrywalla Pub).A Fuss About Queens and Other Stories (Om Books). Read his review of Kedarnath Singh’s poetry ‘BETWEEN THUMBPRINTS AND SIGNATURES’. Also, read his essay on Coming Home to Plato’s Cave in Personal Notes.

More by author in The Beacon

APOSTLESHIP in SANT TUKARAM and ST FRANCIS: STATE of GRACE in CINEMA

Leave a Reply