Vinay Lal

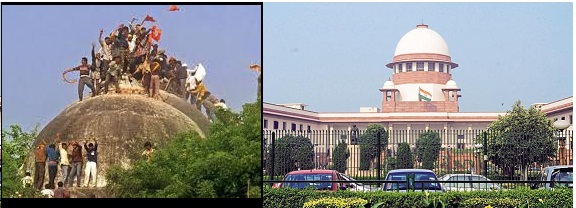

The Supreme Court verdict of November 9th on the Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Masjid title dispute case, resolved unanimously in favor of the Hindu parties, has deservedly come in for much criticism by Muslims, liberals, and many others who remain anguished over the diminishing prospects of secularism, the rise of Hindu majoritarianism, and the future of the Republic. Hindu nationalists have for years been arguing that there are other sacred sites that need to be “liberated”, and few readers are likely to recall that, nearly three decades ago, the journalist, writer, and publisher Sita Ram Goel produced a two-volume work entitled Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them, the first volume of which listed some 2,000 mosques that had been allegedly constructed on the site of Hindu temples. No one with any modicum of learning would care to dignify such a work with the word “scholarship”, but Goel’s compendium reflected the sentiments of a Hindu activist and his co-authors, sentiments that have now been embraced by the nation at large. It is not unnatural that, following the destruction of the Babri Masjid, and the apparent vindication of the claims advanced by Hindu nationalists, the overwhelming fear among Muslims is that other mosques will be similarly targeted. The Hindu soul may yearn for “liberation”, little aware, perhaps, that the present-day language of liberation borrows liberally from the Crusades and the history, which has no parallel in the experience of India, of religious conflict in Europe.

So much has already been said on the Ayodhya matter that it remains unnecessary to recapitulate everything that may be found wanting or contradictory in the court’s judgment. Nevertheless, certain aspects of the ruling will surely continue to puzzle those who have more than a rudimentary understanding of the issues at the heart of the dispute, and therefore warrant some further reflection.

Just how did the Supreme Court, for example, arrive at the view that “on a balance of probabilities, the evidence in respect of the possessory claim of the Hindus to the composite whole of the disputed property stands on a better footing than the evidence adduced by the Muslims” (paragraph 800)?

Large chunks of the voluminous judgment appear to be dedicated to unraveling the “probabilities” that animated the five justices, but still their reasoning comes across as perfunctory.It is striking that Tulsidas, who was born just around the time that the Babri Masjid had been built, and who would go on to win fame as a devotee of Rama sans pareil, had nothing to say about the alleged destruction of a Hindu temple at the supposed Ramjanmasthan. Four centuries later, K. M. Munshi, the chief inspiration behind the restoration of the Somnath temple following the merger of the state of Junagadh into India in the wake of Independence, was similarly reticent on the matter of the Babri Masjid standing forth as an eternal reminder of the humiliation of the Hindu—and this in spite of the fact that he served in Lucknow, in the proximity of Ayodhya, as Governor of Uttar Pradesh from 1952 to 1957.

To use the Supreme Court’s jargon, “on a balance of probabilities” it would seem, from the stunning silence of a whole array of Hindu luminaries, that Hindus were never much agitated by the presence of the Babri Masjid, and certainly never sought its removal. But this never entered into the court’s reasoning, though the failure of Muslims to offer decisive proof that they had possession of the mosque seemed to have moved the five justices. Since the Court admits that Muslims did offer worship from 1857 until 1949, it must have some account of what purpose the Babri Masjid served for the 300 years preceding 1857. It doesn’t.

The Supreme Court ruling is in its spirit contradictory and even disturbing in yet more fundamental ways.

The Court went so far as to say that “the exclusion of the Muslims from worship and possession took place on the intervening night between 22/23 December 1949 when the mosque was desecrated by the installation of Hindu idols. The ouster of the Muslims on that occasion was not through any lawful authority but through an act which was calculated to deprive them of their place of worship” (paragraph 798).

Similarly, the court condemned in clear and unequivocal terms the destruction of the mosque on 6 December 1992 as an “egregious violation of the law” (paragraph 788, sec. XVII). Why, then, should law-breakers and the perpetrators of violence be rewarded rather than penalized, which is doubtless what appears to have happened in this case? It is on much more than the “balance of probabilities” that one would be compelled to think that the Supreme Court has effectively admitted that those who break the law may do so with impunity, since, as in this case, the violation of the law appears to be tolerated on the assumption that it is in the interests of the nation to do so.

Those who have come out in defense of the judgment have of course argued that the Court only weighed in on the matter of whether the Muslims or the Hindus had a better claim to the land, rather than on the moral standing of the parties to the conflict, but this reasoning cannot remotely be reassuring to those who would like the nation to contend with the one indisputable fact: a mosque that once stood there for almost five centuries is no longer in existence. The Court’s tacit uneasiness with its own judgment is conveyed in the ringing declaration that “the Muslims have been wrongly deprived of a mosque which has been constructed well over 450 years ago” (paragraph 798).

It is perhaps for this reason, among others, that the court’s judgment has also come in for some praise, and not only by those who one might expect to be jubilant at the outcome: here the argument seems to be that the Supreme Court had to deal with a very difficult and potentially explosive situation, and that it made the best of an altogether bad situation. The acknowledgment by the court of the harrowing loss of the mosque and the harm to the Muslim community may be read both as an act of contrition and as an exemplary demonstration of the delicate balancing act that judicial bodies in India may have to perform at a time when a Hindu nationalist party controls nearly all the levers of power. The recent statement signed by some 100 Muslims, among them prominent artists, activists, and writers, as well as farmers, engineering students, and home-makers, urging their fellow Muslims to refrain from further litigation cannot of course be construed as signaling their agreement with the Supreme Court’s decision, but it acknowledges the brute fact that “keeping the Ayodhya dispute alive will harm, and not help, Indian Muslims.” Their note makes for painful reading, reminding Muslims that every iteration of the dispute has led to the loss of Muslim lives: “Have we not learnt through bitter experience that in any communal conflict, it is the poor Muslim who pays the price?”

Many commentators of liberal and secular disposition have thus sought to consider the implications of the Supreme Court verdict for the future of the Muslim community. But there is another equally critical, and little considered, question: what does it mean for Hindus?

The supposition that the Muslim is hurting is correct, but does the verdict represent an unadulterated good for the Hindu community? The answer seems too obvious to most commentators to even require mention. The project of building a Hindu rashtra, on this view, has received a massive boost. But does that help the Hindus, or is it only a boon to the BJP and the “Sangh Parivar”: or are we to suppose that they are now one, indistinguishable, something in the manner in which the Nazi party did not merely draw from the volkbut became the volk?

Both the supporters and critics of the court verdict are in agreement that the transformation of India from a secular polity—to the extent that it has been one—to a Hindu nationalist state may be witnessed in most domains of life, from educational and cultural institutions to cultural norms, altered patterns of social intercourse, and claims on the public sphere. The process of altering textbooks to suit new narratives of Hindu glory has been ongoing for many years; it will almost certainly receive more state funding. The secularists will deplore the increasing intolerance on part of Hindus, while the nationalists will argue that, for the first time in a millennium, the Hindu can finally feel at ease in the only country which he can justly call his own. The supposed “tolerance” of the Hindus will, on the secular-liberal view, be put to a severe test and they are almost certainly bound to fail the test; from the standpoint of the Hindu nationalist, Hindus will no longer feel ashamed to own up to their religion and the entire world will be compelled to recognize India for what it is, namely a country that in its origins and soul is fundamentally Hindu.

What is at stake for Hindus is, however, something yet more profound—even chilling.

Let us consider briefly some implications, each of which lends itself to much greater explication. First, Hinduism, as even those who are not Hindus recognize, may reasonably be said to be more accommodating of diversity than any other faith in the world. The committed secularists, liberals, and positivists do themselves no service in rubbishing this argument, and have, at least in small measure, contributed to the present climate of opinion by ridiculing the idea that Hinduism has any special claim to be tolerant. We need not be detained here by the usual rejoinders, among them that Hinduism’s putative “tolerance” did not extend to the lower castes, that Vaishnavas and Shaivas sometimes engaged in violence against each other and against the Buddhists, or that tolerance is at best a mixed virtue: in tolerating the other, the Hindu signifies his superiority to others and demands acceptance of an established hierarchy.

What seems indisputably clear is that some who call themselves Hindus do nothing more than read the Gita, the Ramayana, the Bhagavatam, the Upanishads, or one or more of hundreds of texts; others visit temples; and yet others do neither but may only meditate, perform seva, or undertake a quiet form of puja at home before their ishta devata. One may think of a thousand other scenarios and we would not still be even remotely close to approximating the fecundity and diversity of religious practices that have been gathered under the umbrella of Hinduism. Yet there appears to be a gravitational shift towards “temple Hinduism”, a growing intolerance not merely, as right-minded people would argue, against Muslims and Dalits but rather within the faith itself towards adherents of other practices and conceptions of Hinduism.

Temple Hinduism may be viewed as a mode of establishing communality, but it is also a public display of one’s religious adherence and a tacit declaration of the strength of numbers. The question is whether the Supreme Court verdict does not feed into this worldview of temple Hinduism.

Secondly, if one considers that the entire Ayodhya movement has been a loud, aggressive, and garrulous enterprise, is it not the case that the entire tenor of what it means to be a Hindu has changed radically over the last several decades? Hinduism has never, as I have already suggested, been one thing; nevertheless, the Hinduism that some of us grew up with was the religion of the sants and bhaktas, of sweet and often mesmerizing devotional songs, and of the quiet devotion of one’s mother (and sometimes father) at home. Some scholars and journalists have commented on the staggering popularity of Ramanand Sagar’s epic serial for television, the Ramayana, and the anecdotal evidence of how city streets were emptied of people on something like eighty successive Sunday mornings in 1987-88 when it was screened on the state-run Doordarshan is overwhelming.

But what is rather more striking is the sheer garishness, crudity, and histrionics of Sagar’s Ramayana, an omen of things to come. Not coincidentally, I am inclined to think, the modern phase of the Ayodhya movement started a mere two years later with the rathyatra in 1990, undertaken by L.K.Advani across the country in an air-conditioned Toyota retrofitted as a chariot. It was nothing if not a raucous affair, orchestrated as a spectacle and designed for the media; much the same can be said of the various other stages of this movement, from loud displays of their devotion to the cause by kar sevaks to the very visible, media-driven, and almost outlandish destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

In its verdict, the Supreme Court, which does not appear to have given much thought to this matter, and which in any case would have been outside of its purview, has perhaps inadvertently surrendered to this loud, restless, and even strident form of Hinduism.

Thirdly, the Hinduism of the Ayodhya movement, now vindicated by the Supreme Court judgment, augurs the obsessive cult of muscularity which first appears as an aspiration in the writings of late 19th century figures such as Bankimcandra Chatterjee. Intellectuals and writers began to inquire why the Hindu had allowed himself to be subjugated by foreigners, and Bankim was among those who were certain that the devotionalism of the Hindus had been their wrongdoing.

Nathuram Godse understood Gandhi’s ahimsa as another form of emasculating devotionalism, one beholden to a motley admixture of absurd ideas about the soft nation-state, the good Vaishnava, the efficacy of decidedly irrational practices such as fasting and listening to the small voice within oneself, and the virtues of femininity.

Godse spoke plainly about the fact that, in the brutal and dog eat dog world of modern politics, Gandhi’s advocacy of androgyny and his attempts to feminize the political sphere would be catastrophic for India. Thus the Mahatma had to be eliminated for no other reason than to ensure that the emergent Indian state would not be rendered effete and incapable of defending itself in a world where national interest alone matters.

The Ayodhya movement has taken these arguments further. Anuradha Kapoor wrote on the changing iconography of Ram: in the traditional representation he appeared as a figure reflecting “tranquility, compassion, and benevolence, the shanta rasa”, the Ram of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement had been rendered into a warrior-like figure, “pulling his bowstring, the arrow poised to annihilate.” That was twenty-five years ago.

Now the comparatively new battle cry increasingly enjoins the mob to charge, harass, attack, and kill. In the villages of the Hindi heartland, where the simplest greeting was “Ram Ram” and, especially in religious gatherings, was followed by “Jai Siya Ram”, people have been urged to shout, “Jai Shri Ram”. In the traditional ordering, even in a world that may have been relentlessly patriarchal as a more strident critique of Hinduism might assert, it is significant that Sita takes precedence before Ram: thus “Jai Siya Ram”. The emerging world of a virulent Hindu masculinity, embodied in the Ramjanmabhoomi Movement, is an emphatic repudiation of the devotionalism of popular Hinduism.

Fourthly, however unpalatable such a proposition may be to middle-class Hindus –particularly those who might be described as the most likely supporters of an aggressive Hindu nationalism–Hinduism is a religion of mythos rather than of history. The most remarkable aspect of the dispute over the Babri Masjid – Ramjanmabhoomi site, as I first argued in a lengthy paper just a couple of years after the destruction of the mosque, is the fact that it was fought on the terrain of “history”.

Historians were among the more prominent figures who weighed in on the question of the status of what was called the “disputed structure”, as if in tacit acknowledgement of the extent to which history has become the master discourse of late modernity. Though the secularists and the Hindu nationalists positioned themselves at opposite ends of the ideological spectrum, each camp claimed to have a better historical narrative of the site and its contested history. We may say that both were equally removed from the spirit that has animated Hinduism, the most pronounced feature of which has been that it is singularly devoid of a historical founder, just as it has never had any “scripture”—a word that must always be used advisedly when speaking of Hinduism, and that here I use with extreme reservation—that may be construed as the equivalent of the Quran or the Bible.

No “Hindu” until comparatively recent times was ever bothered by the fact that neither Rama nor Krishna could be viewed as historical figures in the vein of Jesus or Muhammad.

That Hindus were indifferent to such considerations is an extraordinary testament to their ability to live with ambiguity; but what was their most characteristic strength has now been accepted by modern middle-class Hindus as a liability.

History has, alas, monopolized the imagination of the modern Hindu, who is forever smarting under the memory of the humiliations heaped upon him in the past. In the verdict of the Supreme Court we see the tragic and nearly always destructive tethering of history to the telos of the nation-state. Hindus may have won a temple and, as they think, avenged their “humiliation” and gained back their pride, but if the nation continues along this trajectory they would have lost their very religion.

******

Notes This is a greatly expanded and revised version of an essay by the author first published on the ABP Network at abplive.in on 28 November 2019.

Vinay Lal is Professor, History at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), United States. A sample of his extensive writings: Political Hinduism: The Religious Imagination in Public Spheres. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.India and the Unthinkable: The Backwaters Collective on Metaphysics and Politics. Co-edited with Roby Rajan. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016. A Passionate Life: Writings By and On Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay. Co-edited with Ellen C. DuBois. Delhi: Zubaan Books, 2017.Blog:https://vinaylal.

wordpress.com/ Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/ dillichalo

Vinay Lal in The Beacon

Gandhi’s Dharma: Itineraries of a Religious Life Between the Lines

Leave a Reply