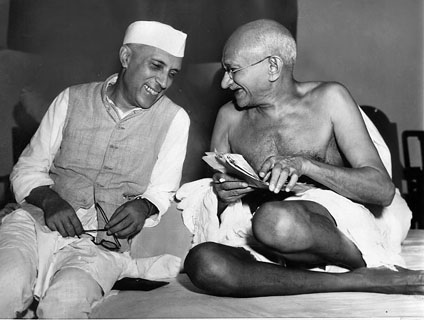

Wikimedia

Prologue

In the late months of 1945, Gandhi and Nehru exchanged a couple of letters, part of the ‘culture of conversation’ that went back decades and continued all through the freedom struggle. Now the correspondences express not just widening disagreements but a decisive ‘break’ between the Father of the Nation and his political heir. The ‘conversations’ represent the final rupture between the two on what the idea of independent India ought to configure.

Gandhi’s isolation from mainstream politics and the leaders of the Congress party including Jawaharlal Nehru had begun much earlier; Sudhir Chandra tells us Gandhi was “as much out of the Congress as he had been in it.” Since 1934 he had ceased being a formal member of the party. And as India’s ‘tryst with destiny’ was becoming a viable option Gandhi was turning even more irrelevant. Chandra cites two observations indicating the way Gandhi was being viewed on the eve of Independence:

Nehru: “As for Gandhiji himself, he was a very difficult person to understand; sometimes his language was almost incomprehensible to an average modern…”

A year later: “I thought of Bapu—so obvious and yet the man of mystery…What a big man he is in spite of everything and whatever the future may hold, it has been a rare privilege to work with him.” (Chandra, 10)

As early as 1942-43 Nehru is impatient to move on with the “average modern:” to bid Gandhi goodbye> Hedged in with so many qualifiers, Nehru’s assertion of the “rare privilege” of working with him has the ring of farewell speeches toasting a departing Chairman of the board. The future for Nehru was being written by him for the average modern and the oddball had no place in it.

****

The letters between the radical visionary and the pragmatic/rationalist statesman at first glance reflect Gandhi’s “intuitive understanding” that begins where “the average modern’s rational comprehension ended.”(Chandra 10) Perhaps one could say, the rational /modern comprehension was incapable of seeing Gandhi’s visions of swarajya as anything more than instrumentalities that had outlived their purpose. The struggle for Independence was coming to an end; victory was at hand and now a new era of practical considerations had to take precedence over possibilities that seemed to the “average modern”, impossible.

In Nehru’s response to Gandhi’s letter of October 5 one can see the conflict of two ideas of progress, of two notions of India (and should we say it?) the death of utopia. As Bharucha dryly observes about Nehru’s prosaic response to Gandhi’s stress on a village-based imaginary: “Unfortunately, Nehru, for all his sophistication, or perhaps because of it, never picked up on these candid clarifications” (Bharucha, 2000). Instead, he proceeds to dismiss villages as culturally and intellectually backward from which no progress could be expected or undertaken.

The letters reproduced here are defining markers for the choices India took, accepting as its leaders did with alacrity the exclusivist rational-modernist path to ‘progress,’ rejecting with as little pause for reflection, the utopian and radical visions of an ageing anarchist. The loss has been ours because that rejection has robbed us of the chance at an engagement, a dialogue with a vision that would have provided a foil to the suicidal rush to consume modernity that is costing us and the planet dear.

We believe the time is upon us to step back from the edge of the precipice, from this “nullity” as Max Weber termed our age, and ‘read’ Gandhi’s dreams, his imagined villages as the wisdom of the future; not of the past.

“Through the unknown, remembered gate,

When the last of the earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;” (T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding)

*****

![]()

MK Gandhi to Jawaharlal Nehru

October 5, 1945

My dear Jawaharlal,

I, have been desirous of writing to you for many days but have not been able to do so before today. The question of whether I should write in English or Hindustani also entered my mind. I have at length preferred to write in Hindustani.

The first thing I want to write about is the difference in outlook between us. If the difference is fundamental then I feel the public should also be made aware of it. It would be detrimental to our work for Swaraj to keep them in the dark. I have said that I still stand by the system of Government envisaged in Hind Swaraj. These are not mere words. All the experience gained by me since 1908 when I wrote the booklet has confirmed truth of my belief. Therefore if I am left alone in it. I shall not mind, for I can only bear witness to the truth as I see it. I have not Hind Swaraj before me as I write. It is really better for me to dream the picture anew in my own words. And whether its the same as I drew in Hind Swaraj or not is immaterial for both you and me. It is not necessary to prove rightness of what I said then, It is essential only to know what I feel today. I am convinced that if India is to attain true freedom and through India the world also, then sooner or later the fact must be recognized that people will have to live in villages, not in towns, in huts not in palaces. Crores of people will never be able to live at peace with one another in towns and palaces. They will then have no recourse but to resort to both violence and untruth. I hold that without truth and non-violence there can be nothing but destruction for humanity. We can realize truth and nonviolence only in the simplicity of village life and this simplicity can best be found in the Charkha and all that the Charkha connotes. I must not fear if the world today is going the wrong way. It may be that India too will go that way and like the proverbial moth burn itself eventually in the flame round which it dances more and more furiously. But it is my burden to protect India and through India the entire world from such a doom. The essence of what I have said is that man should rest content with what are his real needs and become self- sufficient. If he does not have this control he cannot save himself. After all the world is made up of individuals just as it is the drops that constitute the ocean. I have said nothing new. This is a well-known truth.

But I do not think I have stated this in Hind Swaraj. While I admire modern science, I find that it is the old looked at in the true light of modern science which should be reclothed and refashioned aright. You must not imagine that i am envisaging our village life as it is today.

The village of my dreams is still in my mind. After all every man lives in the world of his dreams. My ideal village will contain intelligent human beings. They will not live in dirt and darkness as animals. Men and women will be free and able to hold their own against anyone in the world. There will be neither plague nor cholera nor small pox; no one will be idle, no one will wallow in luxury. Everyone will have to contribute his quota of manual labour. I do not want to draw a large scale picture in detail. It is possible to envisage railways, post and telegraph offices etc. For, me it is material to obtain the real article and the rest will fit into the picture afterwards. If I let go the real thing, all else goes.

On the last day of the working committee it was decided that this matter should be fully discussed and the position clarified after a two or three days’ session. I should like this. But whether the working committee sits or not I want our position vis-à-vis each other to be clearly understood by us for two reasons. Firstly, the bond that unites us is not only political work. It is immeasurably deeper and quite unbreakable. Therefore it is that I earnestly desire that in the political field also should we understand each other clearly. Secondly neither of us thinks himself useless. We both live for the cause of India’s freedom and we would both gladly die for it. We are not in need of the world’s praise. Whether we get praise or blame is immaterial to us. There is no room for praise in this service. I want to live to 125 for the service of India but I must admit that I am now an old man. You are much younger in comparison and I have therefore named you as my heir. I must, however understand my heir and my heir should understand me. Then alone shall I be content.

One other thing. I asked you about joining the Kasturba Trust and the Hindustani Prachar Sabha. You said you would think over the matter and let me know. I find your name in the Hindustani Prachar Sabha. Nanavati reminded me that he had been to both you and Maulana Sahib in regard to this matter and obtained your signature in 1942. That, however is past history. You know the present position of Hindustani. If you are still true to tour signature I want to take work from you in this Sabha. There won’t be much work and you will not have to travel for it.

The Kasturba Fund work is another matter. If what I have written above does not and will not go down with you I fear you will not be happy in the Trust and I shall understand.

The last thing I want to say to you is in regard to the controversy that has flared between you and Sarat Babu. It has pained me. I have really not grasped it. Is there anything more behind what you have said? If so you must tell me.

If you feel you should meet me to talk over what I have written we must arrange a meeting.

You are working hard. I hope you are well. I trust Indu too is fit.

Blessings from

BAPU

*****

Anand Bhavan, Allahabad,

October 9, 1945

MY DEAR BAPU,

I have received today, on return from Lucknow, your letter of the 5th October. I am glad you have written to me fully and I shall try to reply at some length but I hope you will forgive me if there is some delay in this, as I am at present tied up with close- fitting engagements. I am only here now for a day and a half. It is really better to have informal talks but just at present I do not know when to fit this in. I shall try.

Briefly put, my view is that the question before us is not one of truth versus untruth or non-violence versus violence. One assumes as one must that true co-operation and peaceful methods must be aimed at and a society which encourages these must be our objective. The whole question is how to achieve this society and what its content should be. I do not understand why a village should necessarily embody truth and non¬violence. A village, normally speaking, is backward intellectually and culturally and no progress can be made from a backward environment. Narrow-minded people are much more likely to be untruthful and violent.

Then again we have to put down certain objectives like a sufficiency of food, clothing, housing, education, sanitation, etc. which should be the minimum requirements for the country and for everyone. It is with these objectives in view that we must find out specifically how to attain them speedily. Again it seems to me inevitable that modern means of transport as well as many other modern developments must continue and be developed. There is no way out of it except to have them. If that is so inevitably a measure of heavy industry exists. How far that will fit in with a purely village society ? Personally I hope that heavy or light industries should all be decentralized as far as possible and this is feasible now because of the development of electric power. If two types of economy exist in the country there should be either conflict between the two or one will overwhelm the other.

The question of independence and protection from foreign aggression, both political and economic, has also to be considered in this context. I do not think it is possible for India to be really independent unless she is a technically advanced country. I am not thinking for the moment in terms of just armies but rather of scientific growth. In the present context of the world we cannot even advance culturally without a strong- background of scientific research in every department. There is today in the world a tremendous acquisitive tendency both in individuals and groups and nations, which leads to conflicts and wars. Our entire society is based on this more or less. That basis must go and be transformed into one of co-operation, not of isolation which is impossible. If this is admitted and is found feasible then attempts should be made to realize it not in terms of an economy, which is cut off from the rest of the world, but rather one which co-operates. From the economic or political point of view an isolated India may well be a kind of vacuum which increases the acquisitive tendencies of others and thus creates conflicts.

There is no question of palaces for millions of people. But there seems to be no reason why millions should not have comfortable up-to-date homes where they can lead a cultured existence. Many of the present overgrown cities have developed evils which are deplorable. Probably we have to discourage this overgrowth and at the same time encourage the village to approximate more to the culture of the town.

It is many years ago since I read Hind Swaraj and I have only a vague picture in my mind. But even when I read it 20 or more years ago it seemed to me completely unreal. In your writings and speeches since then I have found much that seemed to me an advance on that old position and an appreciation of modern trends. I was therefore surprised when you told us that the old picture still remains intact in your mind. As you know, the Congress has never considered that picture, much less adopted it. You yourself have never asked it to adopt it except for certain relatively minor aspects of it. How far it is desirable for the Congress to consider these fundamental questions, involving varying philosophies of life, it is for you to judge. I should imagine that a body like the Congress should not lose itself in arguments over such matters which can only produce great confusion in people’s minds resulting in inability to act in the present. This may also result in creating barriers between the Congress and others in the country. Ultimately of course this and other questions will have to be decided by representatives of free India. I have a feeling that most of these questions are thought of and discussed in terms of long ago, ignoring the vast changes that have taken place all over the world during the last generation or more. It is 38 years since Hind Swaraj was written. The world has completely changed since then, possibly in a wrong direction. In any event any consideration of these questions must keep present facts, forces and the human material we have today in view, otherwise it will be divorced from reality. You are right in saying that the world, or a large part of it, appears to be bent on committing suicide. That may be an inevitable development of an evil seed in civilization that has grown. I think it is so. How to get rid of this evil, and yet how to keep the good in the present as in the past is our problem. Obviously there is good too in the present.

These are some random thoughts hurriedly written down and I fear they do injustice to the grave import of the questions raised. You will forgive me, I hope, for this jumbled presentation. Later I shall try to write more clearly on the subject.

About Hindustani Prachar Sabha and about Kasturba Fund, it is obvious that both of them have my sympathy and I think they are doing good work. But I am not quite sure about the manner of their working and I have a feeling that this is not always to my liking. I really do not know enough about them to be definite. But at present I have developed distaste for adding to my burden of responsibilities when I feel that I cannot probably undertake them for lack of time. These next few months and more are likely to be fevered ones for me and others. It seems hardly desirable to me, therefore, to join any responsible committee for form’s sake only.

About Sarat Bose, I am completely in the dark; as to why he should grow so angry with me, unless it is some past grievance about my general attitude in regard to foreign relations. Whether I was right or wrong it does seem to me that Sarat has acted in a childish and irresponsible manner. You will remember perhaps that Subhash did not favour in the old days the Congress attitude towards Spain, Czechoslovakia, Munich and China. Perhaps this is a reflection of that old divergence of views. I know of nothing else that has happened.

I see that you are going to Bengal early in November, Perhaps I may visit Calcutta for three or four days just then. If so, I hope to meet you.

You may have seen in the papers an invitation by the President of the newly formed Indonesian Republic to me and some others to visit Java. In view of the special circumstances of the case I decided immediately to accept this invitation subject of course to my getting the necessary facilities for going there. It is extremely doubtful if I shall get the facilities, and so probably I shall not go. Java is just two days by air from India, or even one day from Calcutta. The Vice-President of this Indonesian Republic, Mohammad Hatta, is a very old friend of mine. I suppose you know that the Javanese population is almost entirely Muslim.

I hope you are keeping well and have completely recovered from the attack of influenza.

Yours affectionately,

JAWAHARLAL

MAHATMA GANDHI,

NATURE CURE CLINIC,

6, TODIWALA ROAD, POONA

*****

![]() MK Gandhi to Jawaharlal Nehru

MK Gandhi to Jawaharlal Nehru

November 13, 1945

My dear Jawaharlal,

Our talk of yesterday’s made me glad. I am sorry it could not be longer. I feel it cannot be finished in a single sitting, but will necessitate frequent meetings between us. I am so constituted that, if only I were physically fit to run about, I would myself overtake you, wherever you might be, and return after a couple of days’ heart to heart talk with you. I have done so before. It is necessary that we understand each other well and that others also should clearly understand where we stand. It would not matter if ultimately we might have to differ so long as we remained one at heart as we are today. The impression that I have gathered from our yesterday’s talk is that there is not much difference in our outlook. To test this I put down below the gist of what I have understood. Please correct me if there is any discrepancy.

(1) The real question, according to you, is how to bring about man’s highest intellectual, economic, political and moral development. I entirely agree.

(2) In this there should be an equal right and opportunity for all.

(3) In other words, there should be equality between town dwellers and the villagers in the standard of food and drink, clothing and other living conditions. In order to achieve this equality today people should be able to produce for themselves the necessaries of life i.e. clothing, food-stuffs, dwelling and lighting and water.

(4) Man is not born to live in isolation but is essentially a social animal independent and inter-dependent. No one can or should ride on another’s back. If we try to work out the necessary conditions for such a life, we are forced to the conclusion that the unity of society should be a village, or call it a small and manageable group of people who would, in the ideal, be self-sufficient (in the matter if vital requirements) as a unit bound together in the bonds of mutual co-operation and inter-dependence.

If I find that so far I have understood you correctly, I shall take up consideration of the second part of the question in my next.

I had got Rajkumari to translate into English my first letter to you. It is still lying with me. I am enclosing for you an English translation of this. It will serve a double purpose. An English translation might enable me to explain myself more fully and clearly to you. Further, it will enable me to find out precisely if I have fully and correctly understood you.

Blessings for Indu.

Blessings from

BAPU

———————————— ———————–

References --Letters in order of appearance from: Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Vol 4 --October 5 1947: Gandhi Letter 39: To Nehru --October 9 1945: Gandhi Letter 40: From Nehru --November 13 1945: Gandhi Letter 41: To Nehru Courtesy: http://www.gandhiashramsevagram.org/selected-letters-of-mahatma/gandhi-letter-to-jawaharlal-nehru4.php --Sudhir Chandra: An Impossible Possibility. Translated by Chitra Padmanabhan. Routledge India. November 2016 --Rustom Bharucha: Enigmas of Time. Economic and Political Weekly. March 25 2000. --T.S. Eliot: Collected Pems 1909-1942. P222. Faber and faber1963 Also read in The Beacon: “Hewers of texts…”

Leave a Reply