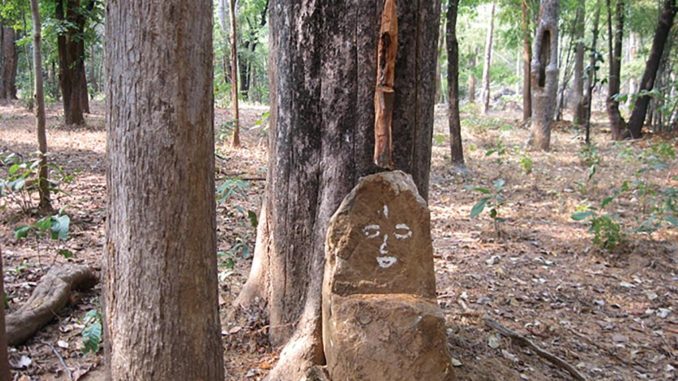

Sacred grove deity in Mendha(Lekha)

Madhav Gadgil

India’s rich heritage of conservation traditions evolved in a society that visualized the world they lived in as a “Community of Beings” involving humans and other beneficent elements such as hills and rivers, woods and trees, birds and monkeys, according such beings respect, even veneration. These traditions were eroded under the influence of the British colonial attitude of man’s “Dominion over Nature” a perspective that viewed natural elements, including living resources as deserving of scant or no respect, only serving the purpose of fulfilling human material needs. The colonial attitude also incorporated contempt for the conquered people, especially the rural and tribal populations that lived close to the natural world and that were repositories of the cultural traditions of nature conservation.

This erosion of conservation traditions accelerated after independence as India fashioned an “economy of violence” obsessed with growth in the Gross Domestic Product at all costs, degrading nature and trampling on people’s constitutional rights in the bargain. India’s conservation traditions can only be revitalized when we accept the moral credo that respect and compassion for nature and people must go hand in hand. This calls for honest implementation of our many constitutional provisions for protection of nature in conjunction with those that empower people to participate in the democratic decision-making process. Two key pieces of legislation in this context include the Biological Diversity Act and the Forest Rights Act. Only when we improve our governance and ensure that such Acts are fully implemented in their true spirit, will we be able to revitalize our conservation traditions and move towards a non-violent, harmonious society.

*****************************************************

“India of the ages is not dead nor has She spoken her last creative word; She lives and has still something to do for herself and the human peoples. And that which must seek now to awake is not an Anglicized oriental people, docile pupil of the West and doomed to repeat the cycle of the Occident’s success and failure, but still the ancient immemorial Shakti recovering Her deepest self, lifting Her head higher toward the supreme source of light and strength and turning to discover the complete meaning and a vaster form of her Dharma. ”

– Sri Aurobindo

I

ndian society is perhaps the world’s most complex society, a mosaic of fishermen and shifting cultivators, toddy tappers and tea estate owners, nomadic shepherds and coal miners, village blacksmiths and computer programmers. Its people dwell in tribal huts in the heart of the rain forests of the Andamans, in fishing hamlets on the Kerala coast, in camps of itinerant well diggers on the Deccan plateau and in villages on the Gangetic plains. They live in the slums of Kolkata and the skyscrapers of Mumbai, in the beach resorts of Goa and pilgrimage centers of the high Himalayas. The diversity of ecological niches that India’s huge population collectively occupies is mind-boggling, as is the variety of belief systems, practices and regulations that govern the utilization of its natural resource base. Many of its towns still harbour wild populations of monkeys thanks to the religious protection they enjoy, although the vast herds of blackbuck that once roamed its countryside are all but gone. While farmers fight bitterly over boundaries of fields in the irrigated tracts of Rajasthan, tribal peoples of the northeast may still practice shifting cultivation on communally owned land. While village grazing lands are encroached upon for cultivation, state forests are dedicated to the production of eucalyptus for industry.

Community of Beings

“The mutual-aid tendency in man has so remote an origin, and is so deeply interwoven with all the past evolution of the human race, that it has been maintained by mankind up to the present time, notwithstanding all vicissitudes of history.”― Pyotr Kropotkin, Mutual Aid

How has this incredible complexity of Indian society developed? Three of the most significant ways in which we humans are unique include our rich symbolic languages, our elaboration of an ever-growing stock of knowledge and our networks of reciprocal relationships transcending ties of kinship. Primitive human societies lived in small hunting-gathering bands cemented by bonds of mutual aid and visualized the world they lived in as a “Community of Beings” involving not only humans, but other beneficent elements such as hills and rivers, woods and trees, birds and monkeys, incorporating such beings in their networks of reciprocal relationships. The creatures they singled out for special respect suggest that they had a deep understanding of their role in the ecological world, for the tree genus considered sacred over large parts of the world is Ficus, including species such as banyan, peepal and gular, a genus that is now designated as a “keystone resource” by ecologists. But knowledge can not only be deployed towards understanding ecological relationships and evolving practices of prudence, but to develop technologies to dominate the natural world. In fact, technologies for manipulating the world, based on an understanding of simpler physical and chemical systems, have grown much faster than those for managing ecological resources that call for an understanding of far more complex systems.

Dominion over Nature

Modern humans originated around 100, 000 years ago, and have lived in small hunting-gathering bands for most of our history, spanning the first 90,000 years or more, with largely equitable access to resources and strong bonds of mutual aid. As humans have progressed technologically, graduating from hunting-gathering to cultivation and animal husbandry and then to industrial and information societies, they have aggregated in ever larger numbers. With their numbers growing, disparities in access to resources have grown, culminating in the emergence of highly exploitative relationships, such as systems of slavery or serfdom. Inter-group rivalries have also escalated, leading to violence, mass killings, even genocide. Simultaneously, many cultures have abandoned the view of a “Community of Beings”, substituting for it man’s “Dominion over Nature”. This spirit has been accompanied by the elaboration of a supposedly scientific framework for managing nature to get the most out of it for people, maximizing yields, hopefully in a sustainable fashion, and conserving elements of nature on the basis of deliberate scientific designsi.

But our scientific understanding of complex ecological systems is very limited; we have no universal laws powerful enough to guide ecological management, equivalent to laws of physics and chemistry that have led to development of technologies enabling us to land on the moon. So the supposedly scientific practices of nature conservation in no way represent a real advance over the traditional folk-knowledge based systems. All that has happened is that the spatial scale of efforts to conserve biodiversity has changed along with enlargement of resource catchments or footprints of modern societies.

Conservation in hunter-gatherer, shifting-cultivator, or so-called horticultural, societies is location-specific and often embedded in nature worship. It includes protection of sacred groves, ponds or river stretches with the protected areas offering a range of use benefits. The scale of such protected areas is typically quite small, often between 1 and 10 hectares and seldom more than 100 hectares. As the footprints of societies have grown so has the scale of protected areas. Agrarian societies protected aristocratic hunting preserves that sometimes extended over thousands of hectares. These also served as sources of fodder, fuel wood and small game for the common people. Modern industrial societies bring in resources from all over the earth; their wild life sanctuaries and national parks range in size from a few square kilometers to thousands of square kilometers[ii]

Regulations: folk and modern

Yet, through all these changes, there is a notable continuity in the forms of restraints on resource use employed whatever the stage of the technological development of the society. These may be broadly classified into six categories:

Restraints on tools: In many Orans, (sacred groves of Rajasthan), wood may be collected, but without using any iron tools. Similarly, modern fishery management practices impose restrictions on minimal mesh size.

Restraints on seasons: In India, many communities suspend hunting during a four-month period, the chaturmas, largely coinciding with the rains. Similarly, modern fishery regulations in India ban fishing in the sea during the monsoon months.

Quantitative restraints on harvests: Members of a given household may carry no more than one head-load of fuel in a week from certain community forests, such as Van Panchayats of Garhwal. Similarly, modem forestry prescriptions permit harvests of a certain proportion of trees of specified size ranges.

Protection to particular life history stages: Many Indian communities protectstorks, pelicans, cormorants at heronries, often located in middle of villages, even though they are hunted outside the breeding season,.Modern day hunting licenses in Western societies similarly prohibit hunting of animals in certain stages of lifer history

Complete protection to all members of some species: Several primate species arc considered sacred and are never harmed in many parts of India. Analogously a number of endangered species are fully protected in many parts of the world today.

Total protection to certain ecosystems: No harvests, even of fallen fruit of commercial value are permitted from certain sacred groves in India. Similarly absolutely no disturbance is permitted in core areas of National Parks.[iii]

Buddha, Buchanan and Brandis

“Throughout the history of our civilization, two traditions, two opposed tendencies, have been in conflict: the Roman tradition and the popular tradition, the imperial tradition and the federalist tradition, the authoritarian tradition and the libertarian tradition.” ― Pyotr Kropotkin, Russian biologist and humanist

Although the nature of modern-day conservation practices has remained pretty much the same as the traditional ones, there is a vast difference in the spirit of implementation. Traditional practices might be viewed in terms of Buddha’s preaching. The Dalai Lama is an able exponent of this philosophical tradition; in an address he delivered in New Delhi on February 4, 1992. he said: “Since I deeply believe that basically human beings are of a gentle nature, so I think the human attitude towards our environment should be gentle. Not only should we keep our relationship with our other fellow human beings very gentle and non-violent, but it is also very important to extend that kind of attitude to the natural environment. So when you say environment, or preservation of environment, it is related with many things. Ultimately the decision must come from the human heart, isn’t that right? So I think the key point is a genuine sense of universal responsibility which is based on love, compassion and clear awareness.”

Buddha’s message clearly is that caring for nature must go hand in hand with respect for fellow human beings.

M

odern nature conservation practices are a legacy of colonial forest administration grounded in a very different mindset of domination over nature and over other people. This is the spirit that animated Francis Buchanan, a Surgeon with the East India Company and a pioneer of Indian botany. He was commissioned by the Company to survey the natural resources of Tipu Sultan’s domains soon after Tipu’s downfall in 1799. Describing a sacred grove near Karwar in coastal Karnataka, he remarks: “The forests are the property of the gods of the villages in which they are situated and the trees ought not to be cut without having obtained leave from the…. priest to the temple of the village god. The idol receives nothing for granting this permission; but the neglect of the ceremony of asking his leave brings vengeance on the guilty person. This seems, therefore, merely a contrivance to prevent the government from claiming the property” (Buchanan 1802; printed 1870)iv.

This attitude of regarding all traditional sustainable use as well as conservation practices merely as impediments to state domination and unrestrained use of the natural resources to serve colonial interests dominated British administrative policy throughout the colonial period. Inevitably, they were accompanied by a feeling of contempt for the conquered people of India.

Yet there were remarkable exceptions, such as Dietrich Brandis, the first Inspector General of Forests under the British regime in India. Brandis was a German botanist and a socialist by leaning. He respected India’s heritage of traditional conservation practices as well as prudent management of forests under village community management. He had this to say of the sacred groves (1897): “Very little has been published regarding sacred groves in India, but they are, or rather were very numerous. I have found them in nearly all provinces. As instances I may mention the Garo and Khasia hills …., the Devarakadus or sacred groves of Coorg Presidency….Well known are the Swami shola on the Yelagiris, the sacred forests on the Shevaroys. These are situated in the moister parts of the country. In the dry region sacred groves are particularly numerous in Rajaputana….. In the southernmost states of Rajaputana, in Partabgarh and Banswara, in a somewhat moister climate, the sacred groves consist of a variety of trees, teak among the number. These sacred forests, as a rule, are never touched by the axe except when wood is wanted for the repair of religious buildings, or in special cases for other purposes”v.

Anjanagandhim, surabhim, bahvannaam, akrusheevalaam

Praham mruganaam maataram, aranyaa neemashamsisham

I praise the forest goddess, fragrant with incense, mother of wild life, who, even though uncultivated, produces an abundance of food!

Aranyasukta, Rigveda

There were many active community-based systems of natural resource management active in pre-British times. Of these, the water management systems were permitted to function under the British regime, since irrigated land could be taxed at a higher rate. These collapsed only after independence; hence, we have a good understanding of many such water management systems and it is acknowledged that a number of them were both economically efficient and socially equitable.

But there is little understanding of the community based forest management systems of the pre-British times. Brandis appreciated these and insisted that the new forestry regime being introduced under the British continue the excellent system of community management of India’s village forests; he was responsible for including this provision in the Indian Forest Act. But Buchanan’s approach totally overwhelmed the Brandisian approach and the Indian Forest Act’s Village Forest provision has been languishing. Community managed forests were all declared illegitimate on the conquest of the British East India Company and there were systematic attempts to discredit and disband the system. But many such as Halakar, Muroor-Kallabbe and Chitragi villages of Karwar district in erstwhile Bombay Presidency survived these assaults. In Rajasthan the village forests in the form of “Orans” were very well managed till the abolition of landlordism after independence. In Goa the local communities or gavkaris had maintained “comunidade” or community lands and water sources, including forests and grazing lands in good shape during the Portuguese regime. In the Central Provinces, too many villages earlier granted Nistar rights over local forests have been managing them well, even to this day. Similarly, many communities of Nagaland are managing their own forest resources very efficiently and sustainably.

Forests and wildlife declined steeply during the colonial regime; the pace of such decline accelerated in the first three decades of independence – through liquidation of private forests, through large scale felling as roads connected hitherto inaccessible regions on account of development projects, through decimation of the resource base of forest based industries practicing excessive, undisciplined harvests. All this served the interests of the ruling classes; it was in no way being driven by the marginalized rural, tribal communities, who were being blamed all the time by officials.

A classic case of how these groups were victimized was that of the village forests of Uttara Kannada district, earlier a part of the Bombay State. Collins, an officer enquiring into forest grievances of the district had special praise for Halakar, Chitragi and Muroor-Kallabbe. He reported that these villages had been managing their village forests exceedingly well for decades, and had set an example that should be widely emulated. These three village forests were established in 1930 as a rare example of implementation of the provision for handing over reserve forests as village forests in the Indian forest Act 1927, on the basis of Collins’s findings. All these village forest committees continued to function well till the linguistic reorganization of the state brought the erstwhile Karwar, renamed Uttara Kannada district to Karnataka. Promptly, the Karnataka forest Department served notice on these Village Forest Committees liquidating them on the pretext that the Karnataka Forest Rules had no provision for village forests. Tragically, the Chitragi villagers totally destroyed their dense forests within fifteen days of receiving the notice, those of Halakar and Muroor-Kallabbe appealed. Finally, people of Halakar won the court case after 28 years of litigation and have continued to manage their village forest very well to this day

Yet, despite this sterling performance they receive no official recognition, although there is an excellent case for the community being given special incentives as “Conservation Service Charges” using the provisions of the Biological Diversity Act, 2002. vi

Assault on conservation traditions

For the first quarter century of independence we regarded dams and power lines as temples of modern India, paying scant attention to the health of India’s natural resource base. But there was a gradual awakening of the need to conserve India’s natural resources in the early 1970’s; this consciousness inspired a series of civil society as well as state-sponsored actions. However, this, in no way dampened the Buchananian spirit prevalent in the Forestry circles. In 1972, when the Chipko Campaign was involving people of Garhwal Himalayas in nature conservation, and when the Wild Life Protection Act was passed, the Karnataka forest department decided to take up commercial tree felling from hitherto protected sacred groves of Coorg, groves that had been enthusiastically praised by Dietrich Brandis. The reason? The large softwood trees, in demand by the plywood industry had been exhausted from the Reserve Forest areas. These trees had been made over to the industry for a pittance, for as low as . 60 for a giant Appimidi mango tree that every year yielded mangoes famous for pickling worth hundreds of rupees.

Since these softwood resources were exhausted, the Forest Department started felling the enormous trees in the sacred groves revered for generations by the people. In Uttara Kannada district, for instance, they clear felled sacred groves extending over hundred or more hectares and replaced them by Eucalyptus plantations. These Eucalyptus plantations later turned out to be miserable failures.

When the Wildlife Act was passed, there was no formal documentation of age old protection methods of heronries such as of pelicans and storks at Kokre Bellur, off Bengaluru-Mysore road in Karnataka. But the name of the village itself is Kokre Bellur, the good village of storks, and this protection extends from before the 1860s, when Jerdon mentions it in his classic volumes on Birds of India. People used the droppings and remains of fish collecting under the nests as an excellent fertilizer for their fields, and happily co-existed with the birds. But how such happy coexistence is threatened once the anti-people state machinery steps in was demonstrated in the village of Nelapattu in Andhra Pradesh. Here pelicans nested on trees fringing an irrigation tank, protected by villagers who waited till the breeding was over, and then used the nutrient rich waters to irrigate their fields[Figure 8].With the Wild Life Protection Act in force, this area was declared a Bird Sanctuary and the Forest Department promptly banned the use of tank for irrigation. This naturally turned the farmers against the birds, hurting simultaneously the cause of nature conservation and agriculturevii.

Garibi Hatao? Oh no, GDP Badhao !

These contradictions are a result of the fact that Independent India has been nurturing an economy in which the rapidly growing organized industries-services sector has developed predatory relations with the natural resource based, labour intensive economy that to this day supports well over two-thirds of the Indian population. The Gandhian economist J C Kumarappa has termed this an “economy of violence”. He pointed out western capitalism had elaborated a capital-intensive economy highly wasteful of natural resources because it had successfully accumulated large capital stocks through draining its colonies, and had access to natural resources of whole continents like the Americas, taken over by wiping out the indigenous people. India did not enjoy that kind of access to capital and natural resources, but had to do justice to its huge pool of human resources.

This called for the prudent use of natural resources, best accomplished by empowering local communities to safeguard and nurture them, and the creation of productive employment on a massive scale. Kumarappa, therefore advocated working out an innovative Indian model of a symbiotic, rather than the Western pattern of predatory development that India had adopted.viii

In 1971 Mrs Indira Gandhi gave the clarion call of “Garibi Hatao”. All empirical evidence suggests that we have far from accomplished this; India now harbours by far the world’s largest concentration of malnourished people. Yet the call of “Garibi Hatao” has now been replaced by one of “GDP Badhao”! It is asserted, in the teeth of accumulating empirical evidence to the contrary, that this growth in GDP would eventually trickle down and with growing prosperity people would ensure environmental protection and social justice. But, it is argued, that all this must wait, and that we must now focus our attention single-mindedly on economic growth, even if it implies flouting our own laws to degrade the environment, and flout our own constitution to mete out social injustice. What we are currently witnessing is not a process of economic growth leading to a trickling down of benefits, but a process of economic growth sucking up resources that sustain many from the weaker sections of society, leading to their further impoverishment and increasing social strifeix.

Over centuries, people at the grass-roots have accomplished a great deal, despite the state continually giving them false promises and weakening people’s organizations, or at hevry least, trying to co-optthe vulnerable into the corrupt system.

All over the country keystone ecological resources like peepal, banyan, gular trees survive in good numbers.

Even today we are discovering new flowering plant species like Kuntsleriakeralensis in sacred groves protected by people in the thickly populated coastal Kerala.

Monkeys, peafowl still survive in many parts of our country.

Numbers of chinkaras, blackbuck, nilgai are actually on increase.

People play a leading role in arresting poachers of animals like blackbuck.

In many parts of Rajasthan people are protecting community forest resources like “Orans”.

In Nagaland many community forests are under good management.

Many Ban Panchayats of Uttaranchal are managing forest recourses prudently.

Many village communities of Central Indian belt are managing well forest resources over which they earlier enjoyed nistar rights.

Village like Halakar in Karnataka is still preserving its village forest well in spite of many attacks by state machinery.

Peasants of Ratnagiri district have ensured good regeneration of their private forests

Thousands of self-initiated forest protection committees of Orissa have regenerated forest brought under community protection.

Indians are very fond of citing the examples of Europe and America. An excellent illustration in this context is that of Switzerland. This hilly country’s forest cover had been largely decimated by 1860’s. But when landslides began to devastate the land, people awakened, and began a concerted effort to grow back forest. Today Switzerland has an excellent forest cover that has grown from a mere 4% to over 60%. But all of it is owned by local communities; none of it by a state forest department.

People\s power and emergent sacred forests

L

ike Orissa state governments, whose sad performance in theNiyamgiri episode was been brought out by the Saxena Committee, Maharashtra state governments too havebeen hell-bent on sabotaging the rights of local communities to promote corporate interests. Regrettably, corporates have decided to push for and take full advantage of an economic growth at-all-costs approach, instead of adopting a broader perspective forin long term social interestsx.

Yet, local struggles can yield positive results as in the case of Gond and other local communities of Gadchiroli and Chandrapur districts of Eastern Maharashtra that have won Community Forest Rights under the Forest Rights Act over extensive areas. They had to struggle hard, for both these districts have substantial mineral reserves [Figure 10]. Fortunately for the people of Gadchiroli, there were some very enlightened officers in the district administration that facilitated the implementation of FRA. But, the struggle has been far harder in Chandrapur district and only one village, that of Pachgaon has been assigned Community Forest Resource area of 1000 hectares.

The conferment of these rights activated the citizens of Pachgaon who decided to work out a whole series of community level regulations not just for the management of Community Forest Resources, but also for the conduct of civil life in their community. The Gramsabha resolved that all must contribute to the formulation of these regulations, and so each household was asked to offer five regulations to kick off the process. This generated a list of some 500 potential regulations, naturally with a lot of overlap. So a committee appointed by the Gramsabha undertook the editorial job and produced a list of about 150 proposals. These were debated by a full meeting of the sabha over two days, leading to the finalization of a list of 40-odd regulations that were adopted by consensus. The entire community was thus party to the decisions arrived at and has now taken to their implementation whole-heartedly.

Notably enough the regulations include setting apart an area of 34 hectares, amounting to 3.4% of the Community Forest Resource area as a strictly protected nature reserve, or in the idiom appropriate to their culture as a Pen Geda or Sacred Grove. This is an area along the crest-line of the hillock within the Community Forest Resource area, with the best preserved natural forest, rich in wildlife and the source of their perennial streams It may be noted that this is close to the proportion of the total forest area of the country set aside as Wild Life Sanctuaries and National Parks. Other interesting regulations agreed upon include a ban on smoking as well as consumption of alcoholic drinks in the village. It so happens that tendu is a major produce from their Community Forest Resource area; these leaves are used for bidi-making. The harvest of tendu leaves entails extensive lopping and setting of forest fires.

So Pachgaon community has decided to forego this income and instead focus on marketing the edible tendu fruit. With stoppage of leaf collection the tendu trees are much healthier and the fruit yield and consequently the income from marketing of the fruit has gone up.

Hamare gamv me ham hee sarakaar!

In contrast to Chandrapur, over 900 villages in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra have won Community Forest Rights under the Forest Rights Act over extensive areas. The struggle for these rights has been pioneered by the citizens of Mendha (Lekha). Beginning with the debate on the Forest Act in 1980’s, they became involved in the Maharashtra-wide movement that had as its motto: Jungle Bachav – Manav Bachav, Save forests to save the people! This movement led to their realizing that there was substantial space in our democratic system for self-governance; indeed that was the ideal that all should work towards. So they injected life into their Gramsabha, ensured that women came to participate fully in its deliberations, set up a self-selecting study circle that carefully looked at issues of interest to the community, and gradually implemented a number of decisions arrived at through “sarvasahamati” or consensus.

Some of the decisions (till the year 2000) included: [1] Prohibiting encroachment on forest land, [2] Initiation and implementation of Joint Forest Management, [3] Daily forest vigilance equally by men and women members. Offenders brought to the village and fined, [4] Outsiders, including paper industriesprohibited from commercial extraction from forest, [5] Bamboo harvest taken over by locals, [6] Ban on cutting fruit trees, [7] Ban on burning wood to prepare fields for cultivation, [8] Wild honey extraction to be permitted without killing bees, [9] Use of Biogas, [10] Equitable distribution of cultured fishes to community members.

Mendha (Lekha) also pioneered the preparation of a People’s Biodiversity Register as a voluntary effort as early as 2004. Villagers realized that the fish resources of the Kathani river in their locality were being adversely affected by use of poisons to catch them. They resolved to ban the use of herbal, and all other fish poisons, not only in Mendha (Lekha), but in all 32 villages that fall in the traditional Ilakha[area]governed by leaders of the Gond community. This ban has now been effectively implemented for the last ten years.

The assignment of Community Forest Rights to the motivated villagers of Mendha (Lekha) as well as to other 900 odd villages of Gadchiroli is promoting prudent resource use in the long term interest of the resource base as well as far greater economic returns to the local community. As in Pachgaon, these communities have also spontaneously decided to set apart substantial areas of the Community Forest Resource areas as strict nature reserves. For Mendha (Lekha) this involves protecting 280.4 or over 15% of the total of 1800 hectares of CFR area The youth especially are motivated to assess the resource base carefully, plan its sustainable use and conservation, work out the potential of local level industrial processing and appropriate marketing strategies. This poses a major scientific and technological challenge and I am personally enthralled at this opportunity of working closely with highly motivated people with a rich store of practical ecological knowledge in a scientific and technological enterprise (Das 2011)xi.

Our tiny neighbor, Bhutan has boldly declared that “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross National Product.” Their policies emphasize the value of nurturing reciprocity, trust amongst all segments of the national society, protecting the environment and ensuring good governance. There can be no disputing that to accomplish these goals respect and compassion for nature and people must go hand in hand. In India, this calls for resolving to implement with sincerity the important pro-nature and pro-people acts such as BDA and FRA that our vibrant democracy has generated. That is clearly the route to revitalizing India’s rich heritage of conservation traditions[xii].

Notes: [i]Gadgil, M. and Berkes, F. 1991. Traditional Resource Management Systems Resource Management and Optimization, 18 (3‑4), 127‑141 [ii]Gadgil, M. 1996. Managing biodiversity, In K.J. Gaston (ed.) Biodiversity : A Biology of Numbers and Difference, pp.345‑365, Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford. [iii] Gadgil, M. 2000. Forging an alliance between formal and folk ecological knowledge.In : World Conference on Science. Science for the Twenty first Century – A New Commitment. UNESCO, 94-97. Gadgil, M. 2005. Practical Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Practices. In Jean-Patrick Le Duc (ed.) Proceedings of the International Conference – Biodiversity Science and Governance, January 24-28, 2005. pp. 148-153. Museum national d’Histoirenaturelle, Paris. [iv]Buchanan (Hamilton), Francis.A Journey from Madras Through the Countries of Mysore, Canara, and Malabar: Performed Under the Orders of the Most Noble the Marquis Wellesley, Governor General of India, for the Express Purpose of Investigating the State of Agriculture, Arts, and Commerce... in the Dominions of the Rajah of Mysore, and the Countries Acquired by the Honorable East India Company... Higginbotham and Company, 1870. [v] Brandis, Dietrich. Indian forestry. Oriental University Institute, 1897 [vi] Mock, G. and Vanasselt, W. (Eds.), Contributing writers :Gadgil, M.et al. Up from the roots : regenerating Dhani forest through community action. In :World Resources 2000-2001 : People and Ecosystems. The Fraying Web of Life. World Resources Institute, Washington D.C. pp. 181-192. [vii]Gadgil,M. and Rao, P.R.S. 1998. Nurturing Biodiversity: An Indian Agenda. Centre for Environment Education, Ahmedabad. p. 163. [viii]Kumarappa, Joseph Cornelius. The economy of permanence.CP, All India Village Industries Assn., 1946. [ix]Gadgil, Madhav 2013.Science, democracy and ecology in India. Nehru memorial Museum and Library.Occasional paper.Perspectives in Indian Development. New Series 12 [x]CBI files chargesheet against Congress MP Vijay Darda, son in coal scam. TNN | Mar 28, 2014, 06.16 AM IST. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/CBI-files-chargesheet-against-Congress-MP-Vijay-Darda-son-in-coal-scam/articleshow/32818852.cms [xi]Das, Dipanita 2011.Mendha Lekha is first village to exercise right to harvest bamboo. TNNApr 23, 2011, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-04-23/pune/29466126_1_forest-rights-act-forest-bureaucracy-minor-forest ************************************************************************* More by Madhav Gadgil: This Land is Our Land: https://www.thebeacon.in/2017/08/30/madhavgadgilfirst/

Leave a Reply