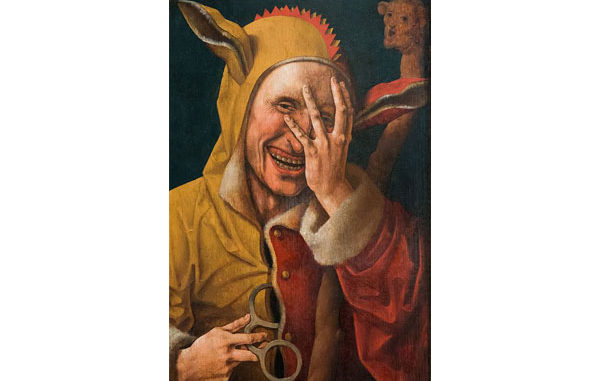

Courtesy Wikimedia commons

Ashoak Upadhyay

E

arly in February the Rajya Sabha, playhouse of decisive inaction and futile activity, witnessed an unusual scene. In the midst of the sonorous intonations of the scholarly Prime Minister who was engaged in his usual experiments with facts history and truth loud laughter, was heard punctuating his dubious assertions. It was Congress Member of Parliament Renuka Chaudhary’s hoots that were echoing across the floor towards the Treasury benches. Her laughter could have drowned the whole world but for now it arched over the heckling of her colleagues.

You can watch this in the video here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bzhsjv5MyC0

At some point it shows Chairman of the Rajya Sabha Venkaiah Naidu trying to quieten the Opposition members down; the video captures his fury at his helplessness perhaps but watch closely and you can hear the insensate fury of a man very quickly stripping himself of the dignity of his office to stand naked as a man, as the member of the community that cannot understand a normal human emotion except as a manifestation of a pathological illness particularly when it manifests itself in women. At that moment, the Chairman had turned Ms. Chaudhary into the Other, a mentally disturbed object that needed treatment; thus his “What happened to you? If you have some problem go see the doctor” (At 2.40 min)

Language says Sinan Antoon, the Arab poet reminds us, isn’t just a means of communication; Naidu wasn’t just admonishing Ms. Chaudhary to hush up; language is a reservoir of memory, tradition and heritage.” Naidu’s peremptory order, to go see a doctor for this “unruly behavior” moved across the precincts of avuncular counsel into the territory of misogyny, of an inherited masculinity that cannot stand women who have crossed the Laxman Rekha of all that a patriarchal society considers women ought to be like, ‘sane’ women that is.

Gesturing to an enraged Naidu to chill, Modi is asking him to leave this raucous female to him; she doesn’t need the whip, she needs the wise crack. That gesture appears like the calming hand of a patriarch, a fury-sodden authority no less, considering what followed; what emerges from the mouth of the Master of the Acerbic Witticism may have seemed, at first glance a tit-for-tat retort about the Ramayana serial and the oblique reference to Shurpanaka’s whacky laugh. It may also appear routine enough for the Treasury benches to have chorused the “witticism” with their own hoots and derisive laughter and desk-thumping. That was the effect intended; everyone would have watched the 1980s serial in its gross interpretations of the epic, its black and white divisions between the good and the evil. It would not have had the same effect had the PM referred to the text itself, for after all, there are 300 hundred Ramayanas and the members from the south may have been sired on Kamban’s version not Valmiki’s that is the basis for the serialised version.

Watch the video closely as the camera swings behind Modi to capture the chorus of derision that erupted; Amit Shah’s manic glee just behind Modi sets the tone of triumphalist derision, evident on all the male members—till the camera pans to the back benches to Nirmala Sitharaman. Her posture is frozen, lips tightly pursed.(At 3.16) She is not controlling a gurgle of a laugh trying to break free; her lips are pursed in the manner of a woman who has stumbled into the thick smog of a stag party’s male jokes.

![]()

Modi’s jibe was “read” plainly enough by his all-male chorus sitting behind; but this is a government in which every attendant-minister has to constantly renew his fealty to the heavy-chested Leader; there was no need for it but the Minister of State for Home Affairs, Kiren Rijiju had to actually describe the nature of the lethal weapon at the core of the Master Wit—just in case all those trolls out there waiting, like Trump’s supporters for the morning tweet, hadn’t got it right! Our Leader had likened the source of that rowdy laughter with Shurpanaka. It did not matter that the young MoS removed the message soon after a privilege motion against him; the point had been made and that point was not only what he intended to establish beyond all doubt but something more. For what he asserts in that show of sycophantic solidarity is his own heritage, history and his identity-politics of assertion. Not the assertion of the quotidian kind, of political power affiliations but an identification with a more substantive power–the capacity to recognize and identify the Other-as-the-Ogre.

Writing in The Indian Express( February 13 2018) Purushottam Agrawal reminds us that Modi takes it upon himself to deal with the laughing lady. That he let the Chairman deal with the male hecklers but wanted to ‘hunt down’ this female who dares to laugh at his corrections of the historical record. But look at the video once again and it is possible that the actions of the Chairman and the PM connote much more than is revealed in the visual. They signify two ends of the spectrum of male reactions to a woman laughing.

In the Chairman’s reactions we see one trope of male reaction to a woman laughing, to what could be considered a ‘Draupadi moment’. It is pure fury at what Naidu considers a pathological condition of human weakness that manifests itself in the feminine persona: that laugh signifies the debasement of reason and rationality, the collapse of a human being’s moral character into the realms of the wicked and the irrational. That is why Naidu considers it his duty, as a member of the rational species to condemn and commend the laughing lady to the care of a ‘doctor’.

The second male reaction is of course Modi’s who feels the only medicine that can ‘cure’ this laughing lady is to mock her into the nether regions occupied by the Woman-Ogre of the popular imagination. On a surface view it is a political act; he condemns an Opposition member as the font of evil, corruption and everything that is base in Indian politics. But read in tandem with Naidu’s fury it represents the male’s assertion of dominant power: Modi ‘curses’ the laughing lady like Durodhana did Draupadi. She joins the ranks of not just Shurpanaka but Mainakini, princess of Sinhala-dvipa who looks up to see a flying chariot with a king whose genitals she can see; an act of humiliation for which she will pay the price by being denied the company of men.

The Chairman of the Rajya Sabha and the Prime Minister and bookend patriarchal norms that isolate laughter and particularly women laughing aspathological behavior of waywardness worthy of physical isolation, medical treatment or punishment through the invocative comparisons with discredited figures in inherited mythologies and memories. By that jibe, Modi, his chorus and attendant-minister Rijiju gave popular mythologies and collective memories about women crossing the limits of ‘normal’ behavior a fresh twist by adding a contemporary face.

II

B

ut Ms. Chaudhary was not cowed down. And why should she be? Laughter has always been considered an important weapon of self-assertion and dissent; conversely, the response of the powerful to women laughing has been uncannily similar across cultures and geographies. Last January, In the United States for instance, Desiree Fairooz, a prominent activist with Code Pink,http://www.codepink.org/about) a women-led grassroots movement against wars, militarism and civil rights abuse was charged for laughing (“disorderly conduct”) during the confirmation hearing of Jeff Sessions as Attorney General. Fairooz burst out laughing during a Republican senator’s introductory remarks extolling Sessions’ treatment of all Americans “equally under the law” Why did she laugh?

“I felt it was my responsibility as a citizen to dissent at the confirmation hearing…”of a man… “who professes anti-immigrant, anti-LGBT policies, who has voted against several civil rights measures and who jokes about the white supremacist terrorist group, the Ku Klux Klan.”

She was convicted in May 2017 but the verdict was overturned by a Supreme Court judge “on the grounds that laughter wasn’t sufficient cause for conviction.” In November the Department of Justice dropped the charges.

Convictions, indictments even death have not deterred victims using laughter or humor as expressions of self-assertion, refusing to be brow beaten into submission. Ashis Nandy reminds us of this in Regimes of Narcissism, regimes of Despair by drawing attention to an essential facet about the master-servant relationship built around humiliation and oppression. The oppressed have to feel humiliated, submit themselves to the subjectivity of the oppressor in order to be humiliated. Laughter allows the victim to escape the will of the oppressor and establish her own identity. “Humiliation can destroy people only by bringing them closer and inducing them to share categories and establish common criteria.” (p155)

He cites the novel, The Dance of Genghis Cohn by the late French novelist Romain Gary. Even in death, Cohn an Auschwitz inmate former Warsaw comedian remains defiant and insolent. He taunts SS officer Schatz, who orders his death, to the point that the guilt-ridden Nazi begins to secretly observe Jewish festivals.

There is a whole corpus of work on the role that humor and laughter played in the Holocaust. Whitney Carpenter’s “Laughter in a Time of Trgedy: Examining Humor in the Holocaust” makes the point that there were “several comedic responses to the Holocaust” Why? “…because (humor) provided an alternative way of internalizing abnormality. It wasa defense mechanism and established a type of revolt…” Laughter and humor were a way of staying human and outside the subjectivity of the oppressor.Hitler did not have a sense of humor, laughed only at the expense of others and, like all dictators, hated being laughed at. The Nazis did everything possible to stamp out political satire or jokes of every kind—except the ones aimed at the victims.

But humor still survived as a weapon of resistance. Carpenter quotes a study by Chaya Ostrower in 2000 of fifty-five Holocaust survivors who unanimously claimed Jewish humor played a prominent role among the prisoners as a defense mechanism.(Carpenter p 7) And why did the Nazis want to eradicate humor? Carpenter quotes a scholar whose words are reminiscent of Nandy’s observations: “The laughter of the oppressed testifies to the existence of an autonomous self who not only exists but also makes choices and thinks outside their ideological framework.” As Carpenter adds: “Humor illustrated the victims’ capabilities for free thought, and to an oppressor what could be more terrifying?”

What indeed? Naidu the Speaker, Modi the Prime Minister and the US administration did not have the maturity to let the the laughing lady have her ‘say’ because their ‘statement’ of laughter expressed an autonomous identity outside the norms of parliamentary or Senate decorum roto be sure but more dangerously for the establishment of patriarichy, they reflected an identity that transgressed historically established standards of behavior expected of women.

III

T

here are times when the most effective way to teach a certain truth is by laughing very hard.” Some critic said that about GK Chesterton’s works. That gem carries within it a potent idea of laughter as a subversive weapon. Perhaps Plato’s warning against laughing excessively because it upset decorum and morality that has found echoes down the ages constitutes the very reasons for common citizens and particularly the Other from “cracking up” as Barry Sanders has suggested.

To her credit Ms Chaudhary gamely retorted after the Modi jibe that there is no GST on laughter, a statement loaded with political intent and an expression of agency. Laughter is as free as air perhaps more so and perhaps less polluted if used by the victims or the transgressed upon to assert an autonomous identity and disown those thrust upon them.

History and literature provide examples of such transgressions of the ordinary, the banal and the routinely superficial or ‘real’ with a deliberate sense of its opposite. Mikhail Bakhtin’s work on Dostoevsky for example draws upon what he calls the “carnival sense of the world” that possesses a “mighty life-creating power, an indestructible vitality.” Bakhtin calls this the genre of the “serio-comical.” (Bakhtin, 107) Among other ‘grotsqueries’ laughter becomes part of the life-affirming, transgressive force. In Bakhtin’s delineation of ‘carnivalesque’ literature one can read as a powerful antidote to repressive power, a statement for change however transitory it may seem.

This concept of “carnivalistic folklore” is vividly illustrated in Rajasthan in the relationship between the Langa sand Manganiyar castes of folk musicians and their jajmans or patrons. The musicians hereditarily relied on their patrons for their livelihood. But the relationship of dependency had its own dialectics. Manganiyars had unique forms of registering their dissatisfaction at the relationship. First, they could stop singing panegyrics to the patron and his family; if that failed then they would bury their turbans just outside their patrons’ house, then their musical instruments’ strings. Finally, if all failed they resorted to the “carinvalesque” coup de grace— tying an effigy of the patron to a donkey’s tail and beating it “ in full view of the neighbourhood.” (Bharucha, 221). This is a manifestation of the “serio-comical” form of reverse humiliation, where the recipients of the patronage system in the caste relationship assert by disowning the traditional forms of behavior and conduct. The process of transgression by the Manganiyars involves heaping public humiliation upon their jajmans. AsBharucha notes “For dissent to exist, the use-value of the object has to be subverted through an act of defiance.”(Bharucha, “Performing…)

The Manganiyars’ carnivalesque moments may have had their intended effects through shock tactics that work to humiliate the patron and rock the patron-client relationship onto a path of correction and address perceived or felt grievances. But in a modern society with its statecraft and instruments of repression through surveillance and thought-management how can the ‘serio-comical’ become a weapon for resistance and protest? How can the irreverent turn into the political?

One outstanding example came on the night of March 03 2016 when, a young man, slight in build, walked casually down the steps of the administrative building in the JNU campus; he was coming home as it were to the sound of another kind of “chorus”. The effect created a carnivalesque space and sound that still resonates two years later for anyone who would care to listen to those moments. What Kanhaiya Kumar and the students who had waited for him did that night was unique: “No political theatre can match the performativity of this political moment beginning with the transformation of space.” (Bharucha, Seminar) Space was altered to create a historic moment when irreverence was distilled into a potent brew with the compounds of political dialogue, rhetoric and with what Bakhtin called “dialogic imagination.”

Listening to Kanhaiya’s speech midst a celebratory spirit, the spirit of “azaadi” reminiscent of the civil rights ‘ freedom marches in the United States and anti-apartheid ones in South Africa, one gets the distinct feeling of bearing witness to a milestone in India’s protracted and tortured haul towards democracy. What we see in that small, beaming figure surrounded by students, holding forth for what seems eternity, –without the aid of notes, without once searching for cues from slips of paper or in an adoring face in the crowd–is a towering vision of India, an inclusive India that marks a radical departure from, indeed stands in opposition to, the kind of inclusiveness peddled through the overheated rhetoric of the ruling power’s jingoism or in discourse as a whole right across the political spectrum.

From the mouth of babes and sucklings as it were, from the rhetoric of the serio-comic we get a dream that recalls Martin Luther King’s “dream” of the re-possession of this land by the exploited. Kanhaiya aims to re-align the positions of the dispossessed back to where they belong; on the same side in the power equation. By referring to himself, a student, as much a son of the soil as the soldier and the farmer, Kanhiaya gave us a glimpse of that republic of the vulnerable; the soldier made to kill an unknown enemy on the borders, the farmer forced into taking his own life because global capitalism had stacked the odds against him and the student struggling for self-worth through the invisible republic of ideas that are termed “anti-national” soon as they take shape Significantly, the policeman too, wielding the lathi, symbol of transmitted power finds a place in this republic of deprivation.

If one listens carefully to his speech one can hear the sounds of walls crashing; walls that the official discourse for decades after Independence has energetically erected to re-locate the Indian people into ghettos, not just literally, as in some states or cities (Mumbra outside Mumbai as “Little Pakistan” or in post-Godhra Gujarat) ) but into ghettos of the mind.

That evening, the sound of demolition comes across as the refrains of a bonding between the speaker and the student-crowd, a life-affirming one in contrast to the chorus behind Prime Minister Modi in Parliament—because it mocks no particular person and yet mocks power.

This resonance of the “refrain” of unity is not just heard in the sloganeering at the end but pervades his speech. Nothing shows this best than the radical use he makes of ‘conversation’, indeed the art of dialogue where positions of ideas and human frailty are outlined to us through the agency of dialogue.

It is this remarkable quality that lends his speech its epic tone; it puts us in mind yet again of what Mikhail Bakhtin said about Dostoevsky’s poetics in which ideas are revealed through dialogues between characters, even within a character.

In his observations on Prime Minister Modi’s reference to Stalin and Khrushchev for instance he uses the poetic of dialogue to great effect; in his “conversations” with the constable to even greater effect. Who knows the context or background of those dialogues with the Haryanvi policeman? Where were they held? Inside his cell? In solitary confinement as he was brought his food?

We get a hint from his mention of the blue and red colored bowls that become in his speech powerful metaphors of that unity between the oppressed classes and castes. This is reminiscent of stand-up comedy dripping with the political. In those conversations what is clear is the first principle of the dialogic art: the barricade between him and the policeman had to be stormed; borders had to be crossed between guard and prisoner.

And the conversation itself?

It is a dialogue of recognition in which there is no resolution except the tacit acknowledgment of victimhood. That too is only hinted at for surely the policeman will revert to his job, certainly not abandon his uniform for the red flag. Yet who knows? And why should we care right now? What we do know is that a dialogue has begun.

The dialogic form as an expression of the carnival esquewas most evident in the slogans at the end of the speech. But these were vastly different from the traditional sloganeering of political parties and unions in India. In Kanhaiya Kumar and his audience providing the chorus of “Azaadi!” we see the musical form of call-and-response of gospel singing, of South Africa’s freedom marches even of the South African jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim’s memorable song, “Mannenberg”.

And most of all we hear and feel an air of festivity. The two-step movement of his body, his right arm, agile and in sync with his calls cast a spell-binding effect of pure rhythm, infectious precisely because it was also a celebration; a theatrical culmination if you wish of a long conversation ending in resolutions that mark the beginning of many more conversations to come.

And the tricolour held aloft by someone in the back rows add sits own dramatic touch to the festival of protest. It seemed to sway to the cadences of the “call and response” chants instead of fluttering disapprovingly from on high above The national flag showers its blessings on the crowd of the wrongfully labeled.

As a metaphor its presence added something equally profound: an irony that should not be lost on all those who thought its towering presence high above the dissident gardens of universities would restrain hot-headed youth.

What Kanhaiya Kumar and his student audience showed us that night when the irreverent met up with the political for a dialogue on dissent and assertion was this: that the tricolour had become the celebratory symbol of a righteous republic by the children of Mother India—a republic whose impressions may be found in subversive laughter and irreverence.

Notes. On the Fairooz/Sessions incident see: https://www.snopes.com/woman-prosecuted-laughing-sessions/ Whitney Carpenter in https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1066&context=religion Barry Sanders: Sudden Glory: Laughter as Subversive History. Beacon Press. New Edition 1996 Mikhail Bakhtin: Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Edited and Translated by Caryl Emerson. Introduction by Wayne C. Booth.2014 edition University of Minnesota Press Rustom Bharucha: Rajasthan: An Oral History. Conversations with Komal Kothari.Penguin India. 2003) --Bharucha. “Performing Dissent” Seminar Magazine. 686. 2016.

Leave a Reply