Ashwani Kumar

Editor’s Note: The best way to introduce the works of Ashwani Kumar, poet, scholar of the marginalised author of “Community Warriors” and other works is through a correspondence with The Beacon.

“A small query. Wondering if possible to blur prose-poetry boundaries and create something like hybrid spaces where we don’t worry much about the craft in the conventional sense…Craft is a technique; used more for consensus rather than ‘dissensus’ and it easily degenerates into an ideology of scientism and power. No wonder, craft is an ally of violence. All dictators and authoritarian rulers love craft not ‘ART’.

“In contrast POETRY is mythic, mimetic and resists oppression and injustice in our everyday lives. This is what poets call the highest form of beauty in which “ what eats is eaten,/and what is eaten, eats/in turn.” (Taittirya Upanishad)!

The Beacon is proud to present some excerpts from the collection. Savour the flavour!

I

Anatomy of Baranassey as told by Major James Rennell*

(Opening Scene; ‘Remember her in your prayers’–said Assi Ghat to a herd of Naga sadhus.)

Bathed in sun and salt,

draped in white loincloth,

she enters the perineum

of the sanctum sanctorum of

buffalo-horned masked ascetic God.

Lions, sitting in cross legged

lotus posture, growl in anticipation

of the procession of voluptuous

cheerleaders with high nose

bridges, slim waists, large hips.

It was the third day of rainbow-lust

in the original Vedas.

Saturn was in the sixth house.

Wives of sages with erring hearts

cooked mutton in clay pitchers,

washed secretly their lovers’ limbs with

the fragrance of their flame-grilled bodies,

and made merry in N and S positions

on the deck of the peacock boat in

the twin rivers of Vara and Nashi.

***

(Act1: Nine Nights of Sacred Love )

From the medieval mosque to apsidal chaityas,

aghoris in twenty-one-yard funeral robes,

flogged by lepers, pimps and bootleggers

throng the gates of Department of

Religious Tolerance and Piety for free passes

to the shrines of nomadic Gods. Parrot-astrologers

and runaway Khalistani terrorists rest on the

staircases of old prostitutes’ homes

in the Assi lane to discuss fluctuating

fortunes of human sacrifice and mustard crop.

Prompted by ancient boons,

she leans geometrically and rubs

vermillion paste on the head of the black lingam,

cradling it gently with her lizard- lips

fledged with spices imported from

Mecca, bursting like a victorious native army.

The love sick Ageing God, lying on a bed of arrows

wakes up from opiate- slumber

in the camphor clouds of sacred ambitions:

trident, drum, conch, and lotus in his hands.

The Auspicious One

frees himself at the first stroke of revelation,

measures rhymes of salvation in metric poems,

recalls how on a wet December morning

He beheaded Brahma on the river front

for smuggling Mongol warriors into the city.

He feels relieved from the

daily chores of eating everybody’s sins

and curses the seven sages for

extolling virtues of celibacy.

***

On the fourteenth night of the

waning moon, she rises

after days of uninterrupted

first-night wedding joys with the Stone-Gods

(that neither we know, nor hear, nor exist any more),

crosses the ghats filled with scattered

feathers of peacocks, sacrifices elongated

riceball–bodies of three-eyed Brahman

ghosts, and strips her bliss naked with the

sacred evening prayer in the river.

We were warned by the famous local bard,

“one half of the city lives in water;

the other half is a dead body (shava)”.

We must confess, we were alarmed

by this unusual sight.

There was neither government,

nor religion, nor any ideology.

Nothing was proscribed,

nothing considered taboo, and civilization existed

in simple geographical coordinates.

***

(Act 2: Sinners in the City of Death)

It was not until late evening

that we realised; celestial gossip-

monger’s warning was right.

A new republic had dawned on the holy town.

With black ink on the index finger,

unbaptized Hindus, prime-time anarchists,

part-time secularists and the

famous Internet Baba had assembled

on the banks of polluted Himalayan river,

and promised to clean accumulated ancient filth.

The great Leader, in golden Afghan jacket,

limited edition watch and Deccan rubber shoes,

tweeted not Solomon’s songs, but spewed lies,

more lies, until they became cobalt truth.

His barbarian followers came with

3D banners, on the back of captured

seahorses from California valley,

levelled the black pillar and chanted

raunchy Bhojpuri songs:

Har, Har Mahadev, Ghar Ghar Mahadev!

***

(To be continued)

(*Only select parts of the lead poem from Banaras and the Other are reproduced here and also slightly modified to suit the operatic performance of the poem. Major James Rennell (1742-1830) was the first Surveyor-General of Bengal. He carried out the first comprehensive geographical survey of much of India. Rennel published ‘The Bengal Atlas’ and ‘Memoir of A map of Hindoostan; or the Mogul Empire’. He is generally considered father of geography in India. Abul Fazal called the holy town Baranassey)

II

Yudhishthira’s Kala Kutta

Where do you come from?

Kosambi, Hastinapur, or Magadh?

“No, No, No.

These were ancient capitals of the North.”

Your eyes are in your head,

you speak with a crooked tongue

in blood-spotted- monosyllables.

“I am terribly sorry.”

But how are you here now?

You are not one of us.

You have no face, no voice of your own.

You look like rubber body bags

exported from cemeteries of Kabul and Kandahar

***

We don’t remember now

if we lived 24/7 in Mano Majra,

or against the bleeding Sun and moon

behind the mountains in Sopore in Kashmir,

but no police torture, rape or pellet firing those days.

We don’t remember

How and when we came to Kala Ghoda.

‘The book of the great journey’ in the epic says,

may be in the year when India got Miss World,

or maybe when Sputnik went into the sky.

Our parents were alcoholic, school dropouts,

they were fortunate as they had neither

land nor local customs. We came here

with our five brothers. Four of them had no

names of their own, so they were called by their

employers: hawker, barber, tailor, bangle-seller.

Only Yudhishthira, who never lied,

followed his family name and occupation.

He cleaned dry latrines with bare hands

in the curated museums.

***

As filth savours itself, smell of the outsiders’

blood becomes the most trusted rave party

drug in the city. We know no honest native

who is not affected by maledictions of the heart,

and the most degenerate become holy cow-worshippers.

After years of struggle in fag-ashed denim trousers,

without any worldly possessions,

the brothers fell one by one on the road to Himalayas.

Only Yudhisthira’s black dog Bruno,

survived the hardships of displacements.

But he got into the strange habit of

peeing on Zebra crossing whenever traffic lights

turned red and eating leftover Jalebis,

thrown around by barbarous firangi tourists

outside Pax Britannica restaurant on Ballard Street!

(This poem is a homage to Arun Kolatkar’s Pi Dog.)

III

Submission to the Good Barbarian

Section 1; Knife the skin of our soul

Turning left or right, short, long, black or white, we turned thirty-five in twenty14. Both of us were lovers and poets though I was also trying my hands at drawing, painting and sculpting mist, darkness and dishonesty in small measures. The idea was to arouse hatred and thirst for blood to gain insight into the innocence of our evil actions.

To test the hypothesis that love is a superstition, we would often knife the skin of our souls as if it were an unpleasant insect or a sacrificial animal. Increasing weariness had made us extricate ourselves from the drubbings of factory work and beauty parlors too. We were corrupted by demolitions of high-rise buildings but still were free of boredom; we would sleep through the day and night in the tiny Inn on the Western Expressway.

My poetic skills were mostly expressions of guilt of sickness with alternative truths. Filling up gaps in the entangled bed-sheets with borrowed testicles of vertical and horizontal desires, we lay naked in alphabetical order and penetrated deep enough, worming our way into bad habits of asking questions about the power of holy men and women.

We realized our stomachs were empty, bones aching and faces had turned turquoise red- an error of judgment or, I was color-blind. My father kept this a family secret. I rubbed my aging ash-grey moustache in her devious ribs, full of strange marks of hand-rolled cigarettes, entering the finishing line in her mouth without realizing that our blood vessels were enclosed by amnesia with unhappiness.

May be I was wrong. May be nothing had happened but she still loved to collect dead butterflies concealed in the cavities of landmines. I wished she would continue to sleep and I would find shelter in the dirty memories of free will. The room was slowly being filled with the opulence of darkness and smell of metaphysical satisfaction for reasons unknown.

I woke up with a gnawing feeling of rats crawling over our bodies or the whirring sounds of flickering tube light in the room, I don’t recall. It was perhaps a loud noise. Our jealous science-fiction writer friend, past his retirement age, was watching religious procession on the television in the reception. He suddenly started banging the doors of empty rooms of tourists. And he was screaming Fascism, Fascism…

Section2: Partisan Review of Bilingual cruelty

We were trembling with fear, shame and ill-conceived arbitrary sins. Strangely, we felt we were in the window-seat: unbuttoned, revealing our bodies like the anecdotal history of revolution in medical sciences.

We heard creaking mysterious sounds as if someone was tossing on his bed and dreaming irrational cheers of experimenting revolutionaries. We realized the mysterious sounds were suppressed shouts of victory of herds of elephant gods trampling baby-faced skulls in the gunny bags left in our room. Unshackling dread of artistic conscience, our souls sank deeper in the discontinuous expression of nocturnal freedoms. Holding pilgrimage to Mecca in my cold arms, knowing that someday special ordinances at Khyber Pass will become poetic license to break out of tradition, we moaned in vague abstractions of the growing terror in the room.

I stood up from the wrought iron bed that my father had stolen from the army camps of the East India Company. In my childhood, there were too many imperfections; bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeoisie were having parties with blood-coated coffee every weekend. We had nothing in our pockets except some loose change of strange whims. We knew that we were on the wrong path but it was the memory of true art that kept our fragmented life-less nation together. I knew she loved another man in a long overcoat. Stripped of her pathological qualities, or mine, in the dim yellow light in the room, it was a nightmare, or deliberate load-shedding along secular principles.

We didn’t know. I looked out of the window. Streets were deserted, desecrated by portly liberals marching along with their old classmates-bald and bleached with prejudice against true patriots. Seeing no escape from the growing darkness in the night, we decided to inject nothingness, the new experiment of honesty, into our veins and regain the health of our motherland. We lay motionless, formless, and shapeless in the bed for hours. Nothing happened. My science-fiction writer friend’s footsteps in the gallery became louder. Moonlight stopped shining on the wicked glass-window. But my dreams of fathering surrogate models of fear in the laboratory happened.

I saw in the room Hobbes, Hegel, Marx, Proudhon and Nietzsche in white frocks eating warm meat of termites spilling out of their rotting books. Seeing all this, my gastronomical desires flared up. I jumped out of the bed, boiled Rumi’s verses in the electric kettle and mixed them with skeletons of the past. I realized there was no one left, and I was alone. She had run away with another man, this time a villager from the land of Buddha. So I drank, smoked the broth and inhaled the irregular geometric lines of atrocities. Hearing more loud sounds of his banging on my door, I slammed the door and closed the latch. But I now genuinely feared the worst- so I started sucking my thumbnail and cried Fascism, Fascism, Fascism…

Later, I find out that she is a celebrity poet. And I am a good artist. I make decent sketches and earn enough. My science-fiction writer friend has passed away. I will not tell you his name. People say he died in a psych ward in a holy city!

(Inspired by Roberto Bolano’s poem ‘Reunion’)

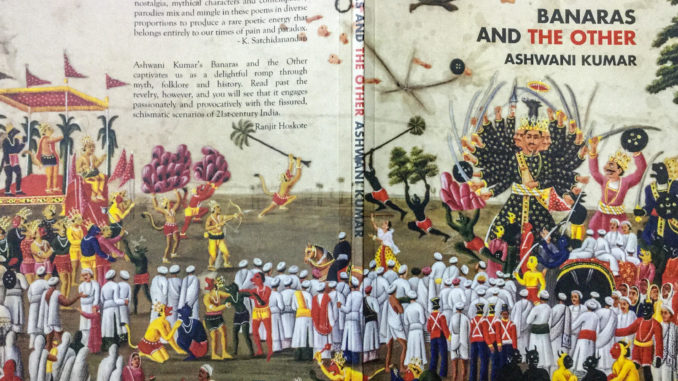

Notes.Excerpts from “Banaras and The Other” (Poetrywala 2017) Ashwani Kumar’s recent collection of poems, part of a trilogy on religious cities in India. Ashwani Kumar is a poet and Professor of development studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Mumbai) His books include My Grandfather’s Imaginary Typewriter (Yeti Books) and Community Warriors (Anthem Press) among others. His poems, reviews and columns are widely published. He has also been a visiting scholar at London School of Economics, German Development Institute, Korea Development Institute, University of Sussex & North West University in South Africa. Presently, he is a Senior Fellow of Indian Council of Social Science Research and researching for a manuscript on welfare regimes in India.

Leave a Reply